new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Early Bird, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 37 of 37

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Early Bird in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/3/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

parliament,

house of commons,

health-care reform,

coalition,

charles w johnson,

house of representatives,

UK politics,

US politics,

william mckay,

Law,

democracy,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

government,

congress,

Early Bird,

Add a tag

Parliament and Congress: Representation and Scrutiny in the Twenty-First Century offers an insiders’ comparative account of the procedures and practices of the British Parliament and the US Congress. In this original post, the authors – William McKay, who spent many years working at the House of Commons and is now an observer on the Council of the Law Society of Scotland, and Charles W. Johnson, who is a Consultant to the Parliamentarian of the US House of Representatives - discuss procedural and institutional developments in both countries over the last few months: in the UK, the new Parliament and coalition government, and in the US, the procedural complexities of the heath care reform bill.

Though the expenses scandal which dominated the parliamentary scene in the UK during 2009 is out of the headlines, it has not gone away. Some of the consequences of the public’s loss of confidence in Parliament are still to be worked out. The new coalition government has brought forward fresh ideas, and parliamentary reform is one of them. Some of these notions are interesting, others more worrying.

The mainspring of the UK constitution is parliamentary democracy. Some recent suggestions seem to diminish the ‘parliamentary’ aspect. One of them, a hangover from the expenses affair, would permit 100 constituents to bring forward a petition which, if signed by 10 percent of a constituency electorate, would vacate the seat of a Member found guilty of wrongdoing, so precipitating a by-election. No one wishes corrupt legislators to retain their seats but existing law already provides that Members of the Commons who are imprisoned for more than a year – those guilty of really serious offences – lose their seats. Secondly, the appropriate way for a parliamentary democracy to deal with offending Members is not for their constituents to punish them but for the House in which the Member sits to do so. The Commons has ample power to expel a Member (the Lords is a more complex matter) though it would be wise to devise more even-handed machinery for doing so than presently exists. Finally, if such a change is to be made, the legislation will have to distinguish very clearly recall on grounds of proven misdoings from opportunist political attacks. It will not be easy.

A further diminution of the standing of Parliament is the proposal for fixed-term Parliaments. It is intended that a Prime Minister may seek a dissolution only when 55 percent of the Commons vote for one. Politically, such a provision would prevent a senior partner bolting a coalition to secure a mandate for itself alone. Constitutionally there are serious disadvantages. A successful vote of no-confidence where the majority against the government was less than 55 percent would not be enough to turn out a government. It might simply lead to frenzied coalition-building, out of sight of the electorate. Governments which had lost the confidence of the Commons could stagger on if they were skilful enough to build a new coalition – for which the country had not voted. During the latest election campaign, concern was expressed that every change of Prime Minister should trigger a General Election. The idea was not particularly well thought-out – how would Churchill have become Prime Minister in 1940? – but nothing could be more at odds with the proposed threshold. Untimely dissolutions happen in two circumstances – when a Prime Minister thinks he can improve his majority and when a government loses a vote of confidence. This proposal tries to restrict the first (which may be a good thing) but does so by interfering with the second, which certainly is not.

In America, the House Committee on Rules drew much attention during the prolonged health care debates in Congress. An understanding of its composition, authority and function

By: Kirsty,

on 6/2/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

hay festival,

hay-on-wye,

town…,

town’,

stalls,

books,

Literature,

UK,

Current Events,

circus,

A-Featured,

castle,

welsh,

Leisure,

festival,

Early Bird,

literary festival,

bookshop,

Add a tag

The Hay Festival of Arts and Literature is one of the highlights of the UK literary calendar. Every year it takes place in Hay on Wye, a small village on the English-Welsh border, famed for its numerous bookshops. This year sees events from lots of big names including AC Grayling, Niall Ferguson, Ian McEwan, and Karen Armstrong. Several OUP authors are also doing events during the festival, including Anthony Julius, Ian Glynn, Robin Hanbury-Tenison, and Jerry Coyne.

OUP UK’s Head of Publicity, Kate Farquhar-Thomson, is also there, and this week will be sending her dispatches from the festival front line. Today, though, she writes about the other side of Hay.

It would be easy to make a list of the stars that I have spotted here at the Hay Festival since I arrived, or indeed the past colleagues I have worked with, but actually what strikes me more, on this visit, is what is going on outside the boundaries of the festival.

The fact is that whilst tens of thousands of people descend on this small Welsh border town for a week (or so) to mingle with politicians, models (oh yes, Jerry Hall was here!), historians, novelists and more, life around the UK’s premier ‘Book Town’ still goes on. I see tractors going about their farm business, sheep lambing and hay being made. However it is not only hay that is being made in Hay by the indigenous population. There are numerous little stalls of bric-a-brac, tea shops, cake stalls and plant sellers that have sprung up in gardens, on pavements, under tents and in driveways. The whole town embraces the festival and is keen to capitalise on it! Good for them I say. It happens but once a year and it is truly special. It is like the circus is in town… all encompassing but transient.

Some of Hay on Wye’s native residents.

Talking of circuses there is actually one in town in the grounds of Hay Castle this year. Giffords Circus, normally to be found every other year in a field just over the Hay Bridge has bedded down in the town centre this year. Within the castle, which was built in 1200, is a flat owned by Richard Booth, the self-proclaimed “King of Hay” whose eponymous bookshop stands at the centre of Hay and was the first second-hand bookshop to open here well over 40 years ago. And for the first time since I have been coming to Hay I actually met the man himself last Saturday night!

By: Kirsty,

on 5/25/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

liberal democrats,

churchill's children,

coalition,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Early Bird,

conservative,

labour,

john welshman,

Add a tag

John Welshman is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Lancaster University. His book, Churchill’s Children: The Evacuee Experience in Wartime Britain, tells the moving real-life stories of British schoolchildren evacuated out of major cities during the Second World War. In the below post, he gives us a bird’s-eye view from the fringes of the first day of the new UK coalition government while in London for a radio interview. You can read his previous OUPblog posts here.

It’s the morning of Wednesday 12 May, and I’m in London to be interviewed by Laurie Taylor on the Radio 4 programme ‘Thinking Allowed’. Selina Todd, from Manchester University, has been asked to contribute her assessment of my book, and so will also be on the show. I know of her work, but haven’t met her previously. The researchers have assured me that Selina likes the book, but she has a formidable reputation, and I worry what she might say.

I’m not due at Broadcasting House until 4pm, so head for WH Smith, and after a quick glance through Time Out, decide to go to the Henry Moore exhibition at Tate Britain. The exhibition has been critically received, but Moore’s work is interesting, especially the early wood and stone carvings of the 1920s and 1930s, and the wartime underground shelter drawings. He made a point of using native materials, such as elm and Hornton stone; elm has a very big and broad grain which makes it suitable for large sculptures. But the later work is less interesting, reclining forms being repeated endlessly, familiar from every New Town park or university campus.

By 1pm, I have had enough, and walk up Millbank towards the London Eye. Maybe the media will still be camped outside the Labour Party headquarters? There is a van with a satellite dish on top, but not a single journalist. Better luck as I round the corner into Parliament Square. Simon Hughes is high up on a gantry being interviewed, and next minute Malcolm Rifkind is walking straight towards me. The mood is infectious; perhaps if I hang around long enough someone will interview me? But perhaps what I could offer is not quite what they’re looking for. I double back and spot a large crowd, so large that I can’t see who’s being interviewed. Soon the reason for the crowd is clear: it’s Ken Clarke. They seem to have a special aura around them, these people familiar from television.

Further up Whitehall there is a large crowd outside Downing Street, spilling over the pavements on to the road itself – policemen, tourists, protesters, schoolchildren, bystanders. Most people’s attention is focused on the main gates, which the police open from time to time to let cars through. But most have no passengers, or the windows are blacked out. The pedestrian entrance to the left seems more promising, and I am rewarded – a constant stream of politicians, photographers, politicians, advisors. If you are quick enough, you can spot them as they go in. BBC Political Editor Nick Robinson arrives, and jokes with a crowd of schoolchildren. ‘Who am I?’ ‘You’re Nick’. Then, ‘are you Nick Clegg’?

I spot the MP for Lancaster and Fleetwood, Eric Ollerenshaw – what can he be doing here? He’s newly elected, so perhaps he’s simply enjoying

By: Kirsty,

on 5/19/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

UK,

Science,

A-Featured,

dunes,

Early Bird,

sphinx,

Egypt,

sand,

geology,

michael welland,

ralph bagnold,

bagnold,

Add a tag

In Sand: A Journey Through Science and the Imagination, geologist Michael Welland weaves together the many facets of sand – its science, its art, its music, its metaphorical power. At every scale, from grain to sand pile to vast deserts, sand is an extraordinary substance. Did you know, for instance, that the sand dunes of Morocco hum a G#? In this excerpt from the book, Michael Welland talks about the pioneering work of sand expert Ralph Bagnold.

The journey of a sand grain tumbling in the wind is a complex one, and while many of the aspects of that journey are understood, there is much, again, that is not. The foundation of what we do know, and of the research desert landscapes that continues today, is entirely the result of the pioneering work of one man (of whom we have already heard)—Ralph Bagnold. Today’s academic textbooks on sand transport often include advice along the lines of ‘for inspiration, read Bagnold (1941)’.

Bagnold’s early encounters with sand occurred after he was posted to Egypt in 1926. Shortly after his arrival in Cairo, he watched the first successful excavation of the Great Sphinx: ‘I watched the lion body of the Great Sphinx being slowly exposed from the sand that had buried it. For ages only the giant head had projected above the sand. As of old, gangs of workmen in continuous streams carried sand away in wicker baskets on their heads, supervised by the traditional taskmaster with the traditional whip, while the appointed song leader maintained the rhythm of movement’ (Sand, Wind, and War). It was never an ideal place to construct one of the world’s great monuments. Arguments about the age and meaning of the Sphinx still rage—there are limitations to the wisdom of that which, according to the Sphinx’s riddle, goes on four legs in the morning, on two legs at noon, and on three legs in the evening (the answer being humankind). However, its link with the building of the pyramids is clear, and King Khafre (or Chephren) was the likely builder. The Great Sphinx has spent most of its existence largely covered by the continuously drifting sand, with only its head, blasted and worn by that sand, protruding. The ravages suffered by the head confirm that the sand that buried the body has been its salvation, preserving it from abrasion. In spite of its role over the centuries as an inspiration for archaeologists, poets, travellers, and those who believe it was built by refugees from Atlantis, its life has largely been like that of an iceberg, demurely hiding its bulk beneath the surface.

It was not until early in the nineteenth century that serious attempts at excavating the Great Sphinx were made, but these were defeated by the enormous volumes of sand involved. Further efforts in 1858 and 1885 revealed a good part of the body and some of the surrounding structures, but these attempts were again abandoned. The Great Sphinx had to wait until 1925 and the arrival of the French archaeologist Émile Baraize for its full glory to be revealed. Removal of the vast quantities of sand required eleven years of labour.

In watching the results of natural sand movements on a staggering scale, Bagnold perhaps had an inkling of the way in which his future would be intimately driven, grain by grain, by sand. The insatiable curiosity that had blowing in the wind possessed him since childhood—from an early age he was ‘aware of an urge to see and do things new and unique, to explore the unknown or to explain the inexplicable in natural science’ (Sand, Wind, and War)—would carry him through an extraordinary diversity of accomplishments until his death in 1990 at the age of 94, still in full stride.

Bagnold was one of those larger-than-life characters, but he was also, unusually, deeply modest.

By: Kirsty,

on 5/11/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

Early Bird,

monarch,

conservatives,

commons,

parliament,

labour,

pact,

hung,

minister,

prime,

hung parliament,

liberal democrats,

Add a tag

Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

For the first time in over 30 years, the British general election last week resulted in a hung parliament. The news is full of the latest rounds of negotiations between the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats, and at the time of writing, we still don’t know who will form the next government.

But what does ‘hung parliament’ actually mean? I turned to the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics to find out.

[Hung parliament is the] name for the situation when after an election no political party has an overall majority in the UK House of Commons. Without a written constitution the response to such a circumstance is governed by statements by courtiers and senior civil servants as to what the constitution requires the monarch to do. The most famous of these statements were by Sir Alan Lascelles, private secretary to George VI, in a letter to The Times in 1950, and by Lord Armstrong, secretary to the cabinet between 1979 and 1987, in a radio interview in 1991.

The incumbent prime minister may continue in office and offer a queen’s/king’s speech: that is, a speech delivered by the monarch but written by the government, outlining its programme. This is likely only if the prime minister’s party still has the largest number of seats, or a pact with another party can be engineered to ensure an overall majority. If the prime minister cannot command the largest party in the Commons and has no pact then the prime minister may ask the monarch to dissolve Parliament and call a further election. In the absence of precedent it remains unclear whether the monarch would be obliged to accede to this request. More likely, the prime minister would resign and advise the monarch upon a successor. Usually the monarch would heed that advice, although in the last resort the monarch is not bound to do so. The new prime minister would then form a government and if a working majority could again not be sustained, a dissolution of Parliament and calling of a second election would be sought and gained from the monarch.

By: Kirsty,

on 5/5/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

constitution,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

election,

A-Featured,

OWC,

Early Bird,

English Constitution,

walter bagehot,

bagehot,

monarchy,

Add a tag

Britain is going to the polls today for what is shaping up to be one of the closest general elections in recent years. The is even a possibility of a hung parliament, with no party winning an overall majority – we can only wait to see what Friday morning brings us. Today, though, I have this short excerpt from The English Constitution by Walter Bagehot. Written in 1867, it is generally accepted to be the best account of the history and working of the British political system ever written. As arguments raged in mid-Victorian Britain about giving the working man the vote, and democracies overseas were pitched into despotism and civil war, Bagehot took a long, cool look at the ‘dignified’ and ‘efficient’ elements which made the English system the envy of the world. The English Constitution was also the inaugural non-fiction book on the week on the Oxford World’s Classics Twitter.

‘On all great subjects,’ says Mr Mill, ‘much remains to be said,’ and of none is this more true, than of the English Constitution. The literature which has accumulated upon it is huge. But an observer who looks at the living reality will wonder at the contrast to the paper description. He will see in the life much which is not in the books; and he will not find in the rough practice many refinements of the literary theory.

It was natural––perhaps inevitable––that such an undergrowth of irrelevant ideas should gather round the British Constitution. Language is the tradition of nations; each generation describes what it sees, but it uses words transmitted from the past. When a great entity like the British Constitution has continued in connected outward sameness, but hidden inner change, for many ages, every generation inherits a series of inapt words––of maxims once true, but of which the truth is ceasing or has ceased. As a man’s family go on muttering in his maturity incorrect phrases derived from a just observation of his early youth, so, in the full activity of an historical constitution, its subjects repeat phrases true in the time of their fathers, and inculcated by those fathers, but now true no longer. Or, if I may say so, an ancient and ever-altering constitution is like an old man who still wears with attached fondness clothes in the fashion of his youth: what you see of him is the same; what you do not see is wholly altered.

There are two descriptions of the English Constitution which have exercised immense influence, but which are erroneous. First, it is laid down as a principle of the English polity, that in it the legislative, the executive, and the judicial powers, are quite divided,––that each is entrusted to a separate person or set of persons––that no one of these can at all interfere with the work of the other. There has been much eloquence expended in explaining how the rough genius of the English people, even in the middle ages, when it was especially rude, carried into life and practice that elaborate division of functions which philosophers had suggested on paper, but which they had hardly hoped to see except on paper.

Secondly, it is insisted, that the peculiar excellence of the British Constitution lies in a balanced union of three powers. It is said that the monarchical element, the aristocratic element, and the democratic element, have each a share in the supreme sovereignty, and that the assent of all three is necessary to the action of that sovereignty. Kings, lords, and commons, by this theory, are alleged to be not only the outward form, but the inner moving essence, the vitality of the constitution. A great theory, called the theory of ‘Checks and Balances,’ pervades an immense part of politica

By: Kirsty,

on 5/4/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

election,

quotations,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

vote,

Early Bird,

governor—reagan,

‘vote,

‘stirring,

stirring,

Add a tag

After four weeks of intense campaigning, the UK general election takes place tomorrow. It seems fitting, then, to take a look at some famous political quotations. I’m delighted to bring you this post by Susan Ratcliffe, Associate Editor of Oxford Quotations Dictionaries. The quotations she has selected come from The Oxford Dictionary of Political Quotations, of which there will be a new edition later this year.

With the long-awaited UK election at last taking place, now is perhaps a good moment to look at some famous (and infamous) words on the subject. The first issue is perhaps just how important voting is. Tom Stoppard’s line: ‘It’s not the voting that’s democracy, it’s the counting’ is well known, but is in fact closely paralled by a remark of Stalin’s in 1923: ‘I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this—who will count the votes, and how’. The importance of counting was recognized long ago: in the early nineteenth century the American politician William Porcher Miles described seeing election banners with the advice: ‘Vote early and vote often’.

Many voters are equally cynical about what is on offer. The American financier Bernard Baruch suggested: ‘Vote for the man who promises least; he’ll be the least disappointing’ while W. C. Fields took a systematic line: ‘Hell, I never vote for anybody. I always vote against’. Ken Livingstone’s view was simple: ‘If voting changed anything, they’d abolish it’.

The candidates themselves are very varied. Winston Churchill described the qualities desirable in a prospective politician many years ago: ‘The ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year. And to have the ability afterwards to explain why it didn’t happen’. David Lloyd George was brutally honest: ‘If you want to succeed in politics, you must keep your conscience well under control’. And more recently Sarah Palin famously described her own qualities: ‘What’s the difference between a hockey mom and a pitbull? Lipstick’.

When the film producer Jack Warner heard that the actor Ronald Reagan was seeking nomination as Governor of California, he reacted unfavourably: ‘No, no. Jimmy Stewart for governor—Reagan for his best friend’. But Reagan went much further than anyone had expected, in the meantime offering this advice to those considering the merits of the various candidates: ‘You can tell a lot about a fellow’s character by his way of eating jellybeans’. A later president, George W. Bush, summed up his opponents in his own unique style: ‘They misunderestimated me’.

Once the campaign is well under way, some things never change. The novelist George Eliot wrote in the nineteenth century: ‘An election is coming. Universal peace is declared, and the foxes have a sincere interest in prolonging the lives of the poultry’. William Whitelaw described a lacklustre Labour campaign of the 1970s: ‘They are going about the country stirring up complacency’, now more commonly quoted as ‘stirring up apathy’. A more heated contest took place in Canada in 2003, where an anonymous press release attacked the Liberal leader in no uncertain terms: ‘Dalton McGuinty: He’s an evil reptilian kitten-eater from another planet’. Rarely do we hear anyone echo Adlai Stevenson in 1952: ‘Better we lose the election than mislead the people’. Sadly, he did lose.

But no matter what the difficulties, most people would agree with Winston Churchill: ‘Democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time’.

By: Kirsty,

on 4/28/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

broken britain,

election,

state,

society,

evacuation,

History,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

conservation,

Early Bird,

john welshman,

Add a tag

The phrase ‘Broken Britain’ is well known to British newspaper readers; it’s a phrase commonly used across the media to describe society’s problems. In the blog post below historian John Welshman, author of Churchill’s Children, traces this identification of a broken society back to around the time of the Second World War, and argues that the real answer is – and was then – to address society’s inequalities rather than ‘Big Society’ and a retreat from state involvement.

You can read John Welshman’s previous posts here. A longer version of this post will appear on the History & Policy website at a later date.

The mantra of ‘Broken Britain’ has been a potent theme for the Conservative Party, its definition effortlessly broadening to encompass whatever appears to be the anxiety of the moment. Iain Duncan Smith has produced an analysis of social breakdown that has five main strands: first, anxiety that a ‘problem’ exists; second, a focus on ‘pathways’ to poverty, covering family breakdown, economic dependency, educational failure, addiction, and personal indebtedness; third, an emphasis that this is ‘lifestyle’ poverty, and not just about money; fourth, a belief in the responsibilities of parents and on the family as the foundation of policy; and fifth, the claim that people themselves, and the voluntary sector, hold the solution. Similarly, the Party’s manifesto argues that a new approach is needed to tackle the causes of poverty and inequality, focusing on social responsibility rather than state control, and on the ‘Big Society’ rather than big government. Only in this way, it is claimed, can ‘shattered communities’ be rebuilt, and the ‘torn fabric’ of society be repaired.

But the identification of a broken society, and these solutions, while current, are nothing new. For exactly the same themes were the subject of debate during the Second World War. In September 1939, carefully-laid plans were put into action, and 1.5m adults and children were evacuated from Britain’s cities to the countryside. If those mothers and children evacuated privately are added to the total numbers, some 3.5 to 3.75m people moved altogether. Those evacuated from England in September 1939 comprised 764,900 unaccompanied schoolchildren; 426,500 mothers and accompanied children; 12,300 expectant mothers; and 5,270 blind people, people with disabilities and other ‘special classes’. The largest Evacuation Areas for unaccompanied schoolchildren (apart from London) were Manchester (84,343); Liverpool (60,795); Newcastle (28,300); Birmingham (25,241); Salford (18,043); Leeds (18,935); Portsmouth (11,970); Southampton (11,175); Gateshead (10,598); Birkenhead (9,350); Sunderland (8,289); Bradford (7,484); and Sheffield (5,338). In Scotland, the largest Evacuation Areas, in terms of accompanied children, were Glasgow (71,393); Edinburgh (18,451); Dundee (10,260); Clydebank (2,993); and Rosyth (540). Given this emphasis upon place, unsurprisingly the evacuation was followed by an outpouring of debate about the state of urban Britain.

It is true that the revolution that took places in English fields and villages seventy years ago was a quiet one. There were much continuity, for instance, in policy between the 1930s and 1940s. Even after the evacuation, civil servants still clung to entrenched attitudes, and continued to put their faith in education, so that Government circulars still tended to emphasise the responsibilities of parents, and to rely on the resources of voluntary organisations. Moreover the pathologising of families remained part of the discour

Curious? Read more, here. And view larger here.

(Oh, and hullo, SFG-ers ... long time, no chat.)

This was done for the quasi-weekly theme draw over at Honor Roll Artworks. I do believe I was the earliest early bird this week.

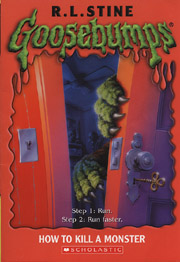

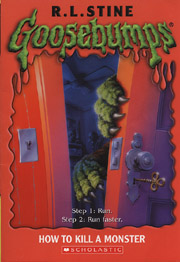

Gretchen and her step-brother,Clark,have to go to there grandparents house for the summer and they hate it there there grandpa is practically deaf and there grandma just wants to bake they have no telephone,no TV,nothing to do but explore.The only thing is that grandpa always eats in his bed in the morning and doesn't eat at the table and grandma makes a ton of food but when it's supper,lunch,or breakfast time she's isn't eating any of it.Nothing else weird write?NOPE,the only last thing is the upstairs room,the one with the key in it,the one that you always here weird noises from and you always see crumbs buy the door...

Gretchen and her step-brother,Clark,have to go to there grandparents house for the summer and they hate it there there grandpa is practically deaf and there grandma just wants to bake they have no telephone,no TV,nothing to do but explore.The only thing is that grandpa always eats in his bed in the morning and doesn't eat at the table and grandma makes a ton of food but when it's supper,lunch,or breakfast time she's isn't eating any of it.Nothing else weird write?NOPE,the only last thing is the upstairs room,the one with the key in it,the one that you always here weird noises from and you always see crumbs buy the door...

What I like about the book is the adventure in it.This book is a lot like other stories that have monsters in it like "Stay Out Of The Basement"the show "Power Puff Girls"except it doesn't have super heroes and fighting and it just has a monster in it that two kids try to kill.

What a cute bird!