new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Poetry, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 4,295

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Poetry in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 7/28/2016

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

fiction,

essays,

Writing,

Theatre,

language,

aesthetics,

Bonnie Nadzam,

Stephen Burt,

LitHub,

Mac Wellman,

Add a tag

Bonnie Nadzam's recent essay at

Literary Hub,

"What Should Fiction Do?", is well worth reading, despite the title. (The only accurate answer to the question in the title [which may not be Nadzam's] is: "Lots of stuff, including what it hasn't done yet...") What resonates for me in the essay is Nadzam's attention to the ways reality effects intersect with questions of identity — indeed, with the ways that fictional texts produce ideas about identity and reality. I especially loved Nadzam's discussion of how she teaches writing with such ideas in mind.

Nadzam starts right off with a bang:

An artistic practice that perpetually reinforces my sense of self is not, in my mind, an artistic practice. I’m not talking about rejecting memoir or characters “based on me.” What I mean is I don’t have the stomach for art that purports to “hold up a mirror to nature,” or for what this implies, philosophically, about selfhood and the world in which we live.

This is a statement that avant-gardes have been making since at least the beginning of the 20th century — it is the anti-

mimetic school of art, a school at which I have long been a happy pupil. Ronald Sukenick, whose purposes are somewhat different to Nadzam's, wrote in

Narralogues that "fiction is a matter of argument rather than of dramatic representation" and "it is the mutability of consciousness through time rather than representation that is the essential element of fiction." Sukenick proposes that all fiction, whether opaquely innovative or blockbuster entertainment, "raises issues, examines situations, meditates solutions, reflects on outcomes" and so is a sort of reasoning and reflection. "The question," he writes, "is only whether a story reflects thoughtfully, or robotically reflects the status quo with no illuminating angle of vision of its own."

|

| Magritte, "The Human Condition", 1933 |

Sukenick, too, disparages the "mirror to reality" or "mirror to nature" idea: "Once the 'mirror of reality' argument for fiction crumbles, possibilities long submerged in our tradition open up, and in fact a new rationale for fiction becomes necessary."

Nadzam's essay provides some possibilities for remembering what has been submerged in the tradition of fiction and for creating new rationales for fiction's necessity:

I want fiction to bend, for its structure not to mirror the reality I think I see, but for its form and structure to help me peel back and question the way reality seems. The way I seem. I love working with the English language precisely because it fails. Even the most perfect word or phrase or narrative can at best shadow and haunt the phenomena of the world. Words and stories offer a way of experiencing being that is in their most perfect articulation a beat removed from direct experience. And so have I long mistrusted those works in which representation and words function without a hiccup, creating a story that is meant to be utterly believed.

Again, not at all new, but necessary because these ideas so push against dominant assumptions about fiction (and reality) today.

An example of one strain of dominant assumptions: Some readers struggle to separate characters from writers. On Twitter recently, my friend Andrew Mitchell, a writer and editor, expressed frustration with this tendency,

saying: "EVERYTHING a character says/does in a story reflects EXACTLY what the writer believes, right? Based on the comments I just read: YES!" As I said to Andrew in reply, this way of thinking results from certain popular types of literary analysis and pedagogy, ones that seek Message from art, ones that want literature to be a paragon of Self Expression, with the Self either a fragile, wounded bird or an allegorical representative of All Such Selfs. It's "write what you know" taken to its logical conclusion: write

only what you know about what and who you are. (Good luck writing a story about a serial killer if you're not one.) Such assumptions are anti-imagination and, ultimately, anti-art.

These dominant assumptions aren't limited to classrooms and naive readers. Consider this, from Achy Obejas's foreword to

The Art of Friction (ed. Charles Blackstone & Jill Talbot):

When my first book, We Came All the Way from Cuba So You Could Dress Like This?, was released in 1994, my publishers were ecstatic at the starred review it received in Publishers Weekly.

But though I appreciated the applause, I was a bit dismayed. The review referred to the seven pieces that comprise the book as “autobiographical essays.” I found this particularly alarming, since six of the seven stories were first-person narrations, mostly Puerto Rican and Mexican voices, while I am Cuban, and one was from the point of view of a white gay man named Tommy who is dying of AIDS.

I’d have thought that the reviewer might have noticed that nationality, race, and gender seemed to shift from story to story—and that is what they were, stories, not essays; fiction, not memoir—but perhaps that reviewer, like many others who followed, felt more comforted in believing that the stories were not products of the imagination but lived experiences.

Imagination is incomprehensible and terrifying. In the classroom, I see this all the time when students read anything even slightly weird — at least one will insist the writer must have been on drugs. When a person reads a work of fiction and their first impulse is to either seek out the autobiographical elements or declare the writer to be a drug addict, then we know that that reader has no experience with or understanding of imagination. For such readers,

based on a true story are the five most comforting words to read.

I come back again and again to a brief passage from one of my favorites of Gayatri Spivak's books,

Readings:

I am insisting that all teachers, including literary criticism teachers, are activists of the imagination. It is not a question of just producing correct descriptions, which should of course be produced, but which can always be disproved; otherwise nobody can write dissertations. There must be, at the same time, the sense of how to train the imagination, so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other. (54)

There must be the sense of how to train the imagination so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other.

To return to Bonnie Nadzam's essay: Another dominant force that keeps fiction from becoming too interesting, keeps readers from reading carefully, and prevents the education of literary imagination is mass media (which these days basically means visual/cinematic media). I love mass media and visual media for all sorts of reasons, but if we ignore pernicious effects then we can't adjust for them. Nadzam writes:

...I’ve noticed that with much contemporary fiction, when we read, we’re often not asked to imagine we’re reading a history, biography, diary or anything at all. Often the text doesn’t even ask the reader to be aware of the text as text. With much fiction, we seem to pretend we are watching a movie. And it is supposed to be a good thing if a novel is “cinematic.”

Much fiction today, especially fiction that achieves any level of popularity, seems to me to draw not just structurally but emotionally from television. At its best, it's

The Wire (perhaps the great melodrama of our era -- and I mean that as high praise); more commonly, it's a Lifetime movie-of-the-week. TV, like pop songs, knows the emotional moves it needs to pull off to make its audience feel what the audience desires to feel -- make your audience feel something they

don't desire to feel, and most of them will turn on you with hate and scorn.

The giveaway, I think, is the narrowness of the prose aesthetic in all fiction that pulls its effects from common wells of emotion, because a complex, unfamiliar prose structure will get in the way of readers drinking up the emotions they desire. Such writing may not itself be inherently rich with emotion; all it needs to do is transmit signs that signal feelings already within the reader's repertoire. Keep the prose structure and style familiar, keep the emotions within the expected range, and the writer only needs to point toward those emotions for the reader to feel them. The reader becomes Pavlov's dog, salivating not over real food, but over the expectation of it. If an identity group exists, then that identity group can train its members toward particular structures of feeling. If the structures are even minimally in place, then members in good standing of an identity group will receive the emotional payoff they desire. Fiction then becomes a confirmation of identity and emotion, not a challenge to it.

(Tangentially: The radical potential of melodrama is to trick audiences into feeling emotions they would not otherwise feel and to complicate expected emotions. This was, for instance, the great achievement of

Uncle Tom's Cabin, a book that is terribly written in all sorts of ways, but which mobilized -- even weaponized -- sentiment to an extraordinary degree. The same could be said for

The Wire, though with significantly less social effect [

Linda Williams has some thoughts on this, if I'm remembering her book correctly].)

Anyone who's taught creative writing will tell you that lots of students don't aspire to write for the sake of writing so much as they aspire to write movies on paper. Which is fine, in and of itself, but if students want to write movies, they should take screenwriting and film production courses. And if I want to watch a movie, I'll watch a movie, not read a book.

Movies, TV, and video games are the dominant narrative forms of our time, so it should be no surprise that fiction often resembles those dominant forms. Even the most blockbustery of bestselling novels can't compete for dominance (and almost every bestselling novel these days is a movie-in-a-book, anyway, so they're just contributing to the dominance). Look how excited people get when they find out their favorite book will be turned into a movie. It's like Pinocchio being turned into a real boy!

What gets lost is

the literary. Not in some high-falutin' sense of the Great Books, but in the technical sense of what written texts can do that other media either can't or don't do as well. Conversely, other media have things they do that written texts don't do as well, or at all — this is what bugs me when people write about films as if they're novels, for instance, because it loses all sense of what is distinctly cinematic. But that's a topic for another time...

Nadzam discusses how she teaches fiction, and I hope at some point she writes a longer essay about this:

When I do “teach” creative writing, I point out that a work of formal realism (which I neither condemn nor condone) usually adheres to a particular formula: Exposition informs a person’s Psychology, from which arises their Character, out of which certain Motives emerge, based upon which the character takes Action, from which Plot results (EPiC MAP). And what formal realism achieved thereby was answering some of the metaphysical questions raised by Enlightenment thinkers about what the self, or character, might be—a person is a noun. A changing noun, perhaps, but a noun nonetheless—somehow separate from the flux of the world they inhabit. The students I’ve had who want to “be writers” hear about EPiC MAP and diligently set to work. The artists in the class, however—the kindred spirits with the mortal wound—they look at me skeptically. Something about that doesn’t feel right, they say. I don’t want to do it that way, they say. Can we break those rules? And each of their “stories” is a terrible, fascinating mess. Are the stories messes because these writers are breaking with habit, forcing readers to break with expectation, or is the EPiC MAP really an effective mirror? I grant that this is an impossible question to answer, but an essential question to raise. By my lights these students are trying, literally, to re-make the world.

This reminded me of Mac Wellman's longstanding practice of encouraging his playwrighting students to write "bad" plays.

The New York Times describes this amusingly:

He asks students to write bad plays, to write plays with their nondominant hands, to write a play that takes five hours to perform and covers a period of seven years. Ms. Satter recalled an exercise in which she had to write a play in a language she barely knew.

“I wrote mine in extremely limited Russian,” she wrote in an email. “Then we translated them back into English and read them aloud. The results were these oddly clarified, quiveringly bizarre mini-gems.”

Mr. Wellman explained: “I’m not trying to teach them how to write a play. I’m trying to teach them to think about what kind of play they want to write.”

Further,

from a 1992 interview:

Inevitably, if you start mismatching pronouns, getting your tenses wrong, writing sentences that are too long or too short, you will begin to say things that suggest a subversive political reality.

One of the most effective exercises I do with students (of all levels) is to have them make a list of "writing rules" — the things they have been told or believe to be key to "good writing". I present this to them seriously. I want them to write down what they really believe, which is often what teachers past have taught them. Then, for the next assignment, I tell them to write something in which they break all those rules. Every single one. Some students are thrilled (breaking rules is fun!), some are terrified (we're not supposed to break rules!), but again and again it leads to some fascinating insights for them. It can be liberating, because they discover the freedom of choice in writing, and do things with words that they would never have given themselves permission to do on their own. It's also educative, because they discover that some of the rules, at least for some situations, make sense to them. Then, though, they don't apply those rules ignorantly and unreflectively: when they follow those rules in the future, they do so because the rules make sense to them.

(I make them read Gertrude Stein, too. I make them try to write like Gertrude Stein, especially at her most abstract. [

Tender Buttons works well.] It's harder than it looks. They scoff at Stein at first, but once they try to imitate her, they struggle, usually, and discover how wedded their minds are to a particular way of writing and particular assumptions about sense and purpose.)

(I show them Carole Maso's book

Break Every Rule. I tell them it's a good motto for a writer.)

To learn new ways to write, to educate our imaginations, we need not only to think about new possibilities but to look at old models, especially the strange and somewhat forgotten ones. Writers who only read what is near at hand are starving themselves, starving their imaginations.

Nadzam returns to 18th century writers, a trove of possibilities:

Fielding thought a crucial and often overlooked aspect of the theatrum mundi metaphor was the emphasis the metaphor puts on the role of the audience, and the audience’s tendency to hastily judge the character of his fellow men. We are not supposed to assume, Fielding’s narrator tells us in Tom Jones, that just because the brilliant 18th-century actor David Garrick plays the fool, Garrick himself is a fool. Nor should we assume that the fool we meet in life is actually—or always—a fool. How then is Fielding’s audience to determine the character of Fielding’s contemporary who plays the part of an actor playing the part of a ghost puppet who represents a real-life individual whose eccentric and condemnable behavior Fielding satirizes? For Fielding, there is no such thing as an un-interpreted experience; an instance of mimetic simulation cannot be considered “truth” (a clear image in a well-polished mirror) because truth itself is the very act of mimetic simulation.

Seeking out writers from before fiction's conventions were conventional helps us see new possibilities. (This is one of the values of

Steven Moore's two-volume "alternative history" of the novel, which upends so many received ideas about what novels are and aren't, and when they were what they are or aren't. Also Margaret Anne Doody's

The True Story of the Novel. Also so much else.)

Finally, one of the central concerns of Nadzam's essay is the way that assumptions about fiction reproduce and reify assumptions about identity:

...what is now generally accepted as “fiction” emerged out of an essentialism that is oddly consoling in its reduction of each individual to a particular set of characteristics, and the reality they inhabit a background distinct from this self. At worst, behind this form are assumptions about identity and reality that may prevent us from really knowing or loving ourselves or each other, and certainly shield us from mystery.

So much fiction seems to see people as little more than roleplaying game character sheets written in stone. Great mysteries of motivation, great changes in conviction or belief, all these too often get relegated to the realms of the "unrealistic" — and yet the true realism is the one that knows our movement from one day to the next is mostly luck and magic.

Relevant here also is

a marvelous essay by Stephen Burt for Los Angeles Review of Books, partly a review of poetry by Andrew Maxwell and Kay Ryan, partly a meditation on how lyric poetry works. More fiction writers ought to learn from poetry. (More fiction reviewers ought to learn from the specificity and attention to language and form in Burt's essay, and in many essays on poetry.) Consider:

A clever resistance to semantic function, an insistence that we just don’t know, that words can turn opaque, pops up every few lines and yet never takes over a reader’s experience: that’s what you get when you try to merge aphorism (general truth) and lyric (personal truth) and Maxwell’s particular line of the North American and European avant-garde (what is truth?). It haunts, it teases, it invites me to return. By the end of the first chapbook, “Quotation or Paternity,” Maxwell has asked whether lyric identification is also escapism: “Trying to identify, it means / Trying to be mistaken / About something else.” Poetic language is, perhaps, the record of a mistake: in somebody else’s terms, we misrecognize ourselves.

And:

We can never be certain how much of our experience resembles other people’s, just as we can’t know if they see our “blue”.... Nor can we know how much of what we believe will fall apart on us next year. ... His poems understand how tough understanding yourself, or understanding anyone else, or predicting their behavior, or putting reflection into words can be, and then forgive us for doing it anyway...

We need more fiction like Stephen Burt's description of Andrew Maxwell's poems: More fiction that understands how tough understanding yourself, or understanding anyone else, or predicting their behavior, or putting reflection into words can be, and then forgives us for doing it anyway.

Jazz Day: The Making of a Famous Photograph

by Roxanne Orgill

illustrated by Francis Vallejo

Candlewick, 2016

Grades 2-6

In 1958, fifty-seven jazz musicians gathered on a street in Harlem to pose for a photo for Esquire. The photo entitled "A Great Day in Harlem" became an iconic image from the 20th century, and the story behind the photograph is amazing.

In this extended picture book, Roxanne

By:

jilleisenberg14,

on 7/18/2016

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading Aloud,

multicultural books,

Educators,

reading comprehension,

close reading,

Educator Resources,

Common Core State Standards,

CCSS,

children's books,

poetry,

diversity,

Add a tag

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year and to recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today as well, as hear from the authors and illustrators.

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year and to recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today as well, as hear from the authors and illustrators.

Featured title: Cool Melons–Turn to Frogs! The Life and Poems of Issa

Author: Matthew Gollub

Illustrator: Kazuko G. Stone

Synopsis: This award-winning book is an introduction to haiku poetry and the life of Issa (b. 1763), Japan’s premier haiku poet, told through narrative, art, and translation of Issa’s most beloved poems for children.

Synopsis: This award-winning book is an introduction to haiku poetry and the life of Issa (b. 1763), Japan’s premier haiku poet, told through narrative, art, and translation of Issa’s most beloved poems for children.

Author Matthew Gollub’s poignant rendering of Issa’s life and over thirty of his best-loved poems, along with illustrator Kazuko Stone’s sensitive and humorous watercolor paintings, make Cool Melons—Turn to Frogs! a classic introduction to Issa’s work for readers of all ages. With authentic Japanese calligraphy, a detailed Afterword, and exhaustive research by both author and illustrator, this is also an inspirational book about haiku, writing, nature, and life.

Awards and honors:

- Notable Books for a Global Society, International Literacy Association (ILA)

- Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts, National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)

- Notable Children’s Trade Books in the Field of Social Studies, Children’s Book Council (CBC) and National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS)

- Children’s Books Mean Business, Children’s Book Council (CBC)

- Not Just for Children Anymore selection, Children’s Book Council (CBC)

- Outstanding Merit, Children’s Book of the Year, Bank Street College of Education

- Best Children’s Books of the Year, Bank Street College of Education

- Books to Read Aloud with Children of All Ages, Bank Street College of Education

- “Editor’s Choice,” San Francisco Chronicle

- Bay Area Book Reviewers Association Award finalist

- Children’s and Young Adult Honorable Mention for Illustration, Asian Pacific American Award for Literature (APAAL)

- “Choices,” Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC)

- ALA Notable Children’s Book, American Library Association (ALA)

- A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book of the Year, The Horn Book Magazine

- California Collections, California Readers

- Utah Children’s Book Award Masterlist

- Children’s Book of Distinction, Poetry Finalist, Riverbank Review

- Read-Alouds Too Good to Miss, Indiana Department of Education

- Starred Review, Publishers Weekly

- Starred Review, The Horn Book Magazine

From the author: “A haiku, because of its brevity, resembles a quick line sketch. It’s up to the reader to imagine the details and to make the picture complete. In a sense, we can think of a haiku as a telegraph; for example: “Should arrive Tuesday, supper time.” From this short message, we can infer that, weather permitting, the sender will arrive early on Tuesday evening, and that after the long, tiresome journey she would appreciate a good meal.

Often, haiku describe two events side by side, such as: “Plum tree in bloom—/ a cat’s silhouette/ upon the paper screen.” Does the silhouette of the plum tree also appear on the paper screen? Does the plum tree in bloom suggest the warmth of a spring day? Again, it’s up to the reader to imagine how or if the two things are related.

Haiku tend to be simple and understated, so there’s never one “correct” way to interpret them. The idea is to ponder each poem’s imagery and to discover and enjoy how the poem makes you feel.”

–Matthew Gollub, from “What is a Haiku?“

Resources for teaching with Cool Melons–Turn to Frogs! The Life and Poems of Issa:

Book activity:

Expand students’ experience with haiku by having them read and discuss works by other seventeenth century and eighteenth century poets such as Basho, Jöso, Ryota, Buson, or Sanpu. Students may also enjoy reading more contemporary haiku and comparing the contemporary poetry with the more traditional.

How have you used Cool Melons–Turn to Frogs! The Life and Poems of Issa? Let us know!

How have you used Cool Melons–Turn to Frogs! The Life and Poems of Issa? Let us know!

Celebrate with us! Check out our 25 Years Anniversary Collection.

Poems in the Attic. Nikki Grimes. Illustrated by Elizabeth Zunon. 2015. Lee & Low. 48 pages. [Source: Library]

First sentence: Grandma's attic is stacked with secrets.

Premise/plot: Poems in the Attic is a picture book about a seven year old girl who discovers a box of her mother's poems in her grandmother's attic. Her mother started writing poems when she was just seven. Our heroine, the little girl, decides to start writing poems of her own. Readers see these poems--mother and daughter--side by side. The mother's poems are about growing up a 'military brat' moving from place to place every year or so. The daughter's poems are doubly reflective.

My thoughts: I liked this one. I liked the premise of it especially. A girl coming to appreciate her mother in a new light. A girl learning to express herself through poetry. The book celebrates family, poetry, and a sense of life as one big adventure.

That being said, poetry tends to be hit or miss with me. I sometimes enjoy poetry. Sometimes not so much. I didn't love the short poems in this one as much as I wanted. I liked them okay. I just wasn't WOWED by them. I do like the celebration of family. And the illustrations were great. Eleven places were captured in the mother's poems. And the author's note was interesting. So this one is worth your time.

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Our last "in the style of" challenge was e.e. cummings, a poet of invented words and experimental forms, a writer who easily charms me, and often transports me. This time, our poet model is Kay Ryan, U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner, who says in this Paris Review interview:

"Prose is practical language. Conversation is practical language. Let them handle the usefulness jobs. But of course, poetry has its balms. It makes us less lonely by one. It makes us have more room inside ourselves. But it’s paralyzing to think of usefulness and poetry in the same breath."

And yet, I find it amusing that when I read Kay Ryan's poetry, she seems to be playing with this idea of usefulness. Her poems are often skirmishes with well-worn phrases---she calls herself "a rehabilitator of clichés"---and she deploys flatly-voiced "advice" so wryly you have to read her poems over to see where the joke is. It's like she's saying: why, here's a good (useful) idea---whatever the haha hell that is.

In the same interview, in fact, she says:

"what interests me is so remote and fine that I have to blow it way up cartoonishly just to get it up to visible range."

Yes. I see that. And I found reading the entire Paris Review interview a pleasure and a learning experience and very welcoming. Climbing inside a poem of hers, in order to "echo" it, however, was damn hard.

The first fear

being drowning, the

ship’s first shape

was a raft, which

was hard to unflatten

after that didn’t

happen.

There is slant, internal rhyme there---unflatten and happen---and repetition of words---first fear, first shape---and of course, that arresting phrase "the first fear being drowning." Okay, I could work with that. Or so I thought.

To begin, I tried to riff off that opening phrase, and immediately foundered on the rocks of "drowning." Every kind of "-ing" that meant death seemed to already be a form of drowning---asphyxiating, choking, strangling---because breathing is the foundation of life, and anything that stops it is death. So...drowning seemed the plainest, most Ryan-like word to use, and death, obviously was the "first fear" and I had no interest in writing about second or third ones, and yet---I couldn't use her opening exactly, could I? She had laid her planks so precisely that if I did, I didn't know where I would stop copying and start riffing, and I might just end up with the same poem, word for word. Upon reading---and re-reading---her poem, it just didn't seem like it could be written any other way. (Read it here, now, and see if you agree.)

Then, thank goodness, I recalled the part of the interview in which Ryan talks about her time working with prisoners at San Quentin. She says:

"I’m rather shocked to look back at the way I thought of the prisoners at that time—as people with a lot of experience. Just because they’re killers and robbers and whatnot doesn’t mean they’ve had a lot of experience. It doesn’t take very long to kill somebody."

Well, I thought, the same could be true of my foundering effort: it doesn't take very long to kill a draft, either. Especially when the well-experienced Ryan has drowned every word you could possibly use. Haha.

That did it. I decided to go another way to echo this poem: fear of emotional death, or to put it plainly, shame, or fear of failing.

This is a very long lead up to a very short poem. But echoing Kay Ryan will do that to you. No wonder she chooses to only write poetry. It is usefully sharp and murderous.

"It doesn't take very long to kill somebody"

The first fear

being shaming,

the poet’s first line

was a circle, which

was hard to deflate

after that didn’t

take. It’s cumbersome

to have to scrub one’s blood

from words, so hard to

hide later,

drubbing one’s thumb

into a nose—

making things

more lovable.

---Sara Lewis Holmes, all rights reserved

My Poetry Sisters each chose other Kay Ryan poems to "echo"---and pulled the challenge off much better than I did. Go see:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/29/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

picture book poetry,

African-American authors and illustrators,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 poetry,

Reviews,

history,

poetry,

Simon and Schuster,

Atheneum,

Best Books,

Ashley Bryan,

multicultural children's literature,

African-American history,

Add a tag

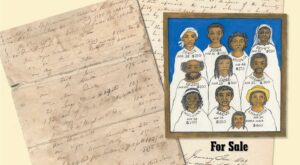

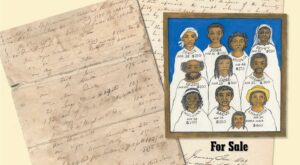

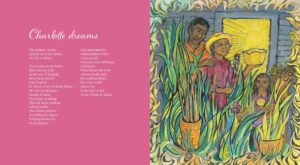

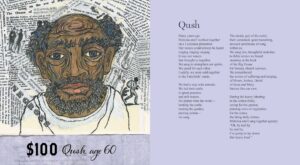

Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life

Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life

By Ashley Bryan

Atheneum (an imprint of Simon & Schuster)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1481456906

Ages 9 and up

On shelves September 13th

Who gives voice to the voiceless? What are your credentials when you do so? When I was a teen I used to go into antique stores and buy old family photographs from the turn of the century. It still seems odd to me that this is allowed. I’d find the people who looked the most interesting, like they had a story to tell, and I’d take them home with me. Then I’d write something about their story, though mostly I just liked to look at them. There is a strange comfort in looking at the faces of the fashionable dead. A little twinge of momento mori mixed with the knowledge that you yourself are young (possibly) and alive (probably). It’s easy to hypothesize about a life when you can see that person’s face and watch them in their middle class Sunday best. It is far more difficult when you have no face, a hint of a name, and/or maybe just an age. Add to this the idea that the people in question lived through a man made hell-on-earth. When author/illustrator/artist Ashley Bryan acquired a collection of slave-related documents from the 1820s to the 1860s he had in his hands a wealth of untold stories. And when he chose to give these people, swallowed by history, lives and dignity and peace, he did so as only he could. With the light and laughter and beauty that only he could find in the depths of uncommon pain. Freedom Over Me is a work of bravery and sense. A way of dealing with the unimaginable, allowing kids an understanding that there is a brain, heart, and soul behind every body, alive or dead, in human history.

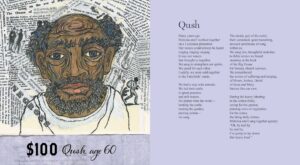

The date on the Fairchilds Appraisement is July 5, 1828. On it you will find a list of goods to be sold. Cows, hogs, cotton . . . and people. Eleven people, if we’re going to be precise (and we are). Most have names. One does not. Just names on a piece of paper almost 200-years-old. So Ashley Bryan, he takes those names and those people, and for the first time in centuries we get to meet them. Here is Athelia, a laundress who once carried the name Adero. On one page we hear about her life. On the next, her dreams. She remembers the village she grew up in, the stories, and the songs. And she is not alone in this. As we meet each person and learn what they do, we get a glimpse into their dreams. We hear their hopes. We wonder about their lives. We see them draw strength from one another. And in the end? The sale page sits there. The final words: “Administered to the best of our Judgment.”

I have often said, and I say it to this day, that if there were ever a Church of Ashley Bryan, every last person who has ever met him or heard him speak would be a member. There are only a few people on this great green Earth that radiant actual uncut goodness right through their very pores. Mr. Bryan is one of those few, so when I asked at the beginning of this review what the credentials are for giving voice to the voiceless, check off that box. There are other reasons to trust him, though. A project of this sort requires a certain level of respect for the deceased. To attain that, and this may seem obvious, the author has to care. Read enough books written for kids and you get a very clear sense of those books written by folks who do not care vs. folks that do. Even then, caring’s not really enough. The writing needs to be up to speed and the art needs to be on board. And for this particular project, Ashley Bryan had a stiffer task at hand. Okay. You’ve given them full names and backgrounds and histories. What else do they need? Bryan gives these people something intangible. He gives them dreams. It’s right there in the subtitle, actually: “Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life.”

I have often said, and I say it to this day, that if there were ever a Church of Ashley Bryan, every last person who has ever met him or heard him speak would be a member. There are only a few people on this great green Earth that radiant actual uncut goodness right through their very pores. Mr. Bryan is one of those few, so when I asked at the beginning of this review what the credentials are for giving voice to the voiceless, check off that box. There are other reasons to trust him, though. A project of this sort requires a certain level of respect for the deceased. To attain that, and this may seem obvious, the author has to care. Read enough books written for kids and you get a very clear sense of those books written by folks who do not care vs. folks that do. Even then, caring’s not really enough. The writing needs to be up to speed and the art needs to be on board. And for this particular project, Ashley Bryan had a stiffer task at hand. Okay. You’ve given them full names and backgrounds and histories. What else do they need? Bryan gives these people something intangible. He gives them dreams. It’s right there in the subtitle, actually: “Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life.”

And so the book is a work of fiction. There is no amount of research that could discover Bacus or Peggy or Dora’s true tales. So when we say that Bryan is giving these people their lives back, we acknowledge that the lives he’s giving them aren’t the exact lives they led. And so we know that each person is a representative above and beyond the names on that page. Hence the occupations. Betty is every gardener. Stephen every architect. Dora every child that was born to a state of slavery and labored under it, perhaps their whole lives. And there is very little backmatter included in this book. Bryan shows the primary documents alongside a transcription of the sales. There is also an Author’s Note. Beyond that, you bring to the book what you already know about slavery, making this a title for a slightly older child readership. Bryan isn’t going to spend these pages telling you every daily injustice of slavery. Kids walk in with that knowledge already in place. What they need now is some humanity.

Has Mr. Bryan ever done anything with slavery before? I was curious. I’ve watched Mr. Bryan’s books over the years and they are always interesting. He’s done spirituals as cut paper masterpieces. He’s originated folktales as lively and quick as their inspirational forbears. He makes puppets out of found objects that carry with them a feeling not just of dignity, but pride. But has he ever directly done a book that references slavery? So I examined his entire repertoire, from the moment he illustrated Black Boy by Richard Wright to Susan Cooper’s Jethro and the Jumbie to Ashley Bryan’s African Folktales, Uh-Huh and beyond. His interest in Africa and song and poetry knows no bounds, but never has he engaged so directly with slavery itself.

Has Mr. Bryan ever done anything with slavery before? I was curious. I’ve watched Mr. Bryan’s books over the years and they are always interesting. He’s done spirituals as cut paper masterpieces. He’s originated folktales as lively and quick as their inspirational forbears. He makes puppets out of found objects that carry with them a feeling not just of dignity, but pride. But has he ever directly done a book that references slavery? So I examined his entire repertoire, from the moment he illustrated Black Boy by Richard Wright to Susan Cooper’s Jethro and the Jumbie to Ashley Bryan’s African Folktales, Uh-Huh and beyond. His interest in Africa and song and poetry knows no bounds, but never has he engaged so directly with slavery itself.

Could this have been done as anything but poetry? Or would you even call each written section poetry? I would, but I’ll be interested to see where libraries decide to shelve the book. Do you classify it as poetry or in the history section under slavery? Maybe, for all that it seems to be the size and shape of a picture book, you’d put it in your fiction collection. Wherever you put it, I am reminded, as I read this book, of Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! where every lord and peasant gets a monologue from their point of view. Freedom Over Me bears more than a passing similarity to Good Masters. In both cases we have short monologues any kid could read aloud in class or on their own. They are informed by research, and their scant number of words speak to a time we’ll never really know or understand fully. And how easy it would be to turn this book into a stage play. I can see it so easily. Imagine if you turned the Author’s Note into the first monologue and Ashley Bryan his own character (behold the 10-year-old dressed up as him, mustache and all). Since the title of the book comes from the spiritual “Oh, Freedom!” you could either have the kids sing it or play it in the background. And for the ending? A kid playing the lawyer or possibly Mrs. Fairchilds or even Ashley comes out and reads the statement at the end with each person and their price and the kids step forward holding some object that defines them (clothing sewn, books read, paintings, etc.). It’s almost too easy.

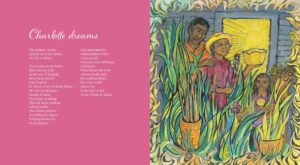

The style of the art was also interesting to me. Pen, ink, and watercolors are all Mr. Bryan (who is ninety-two years of age, as of this review) needs to render his people alive. I’ve see him indulge in a range of artistic mediums over the years. In this book, he begins with an image of the estate, an image of the slaves on that estate, and then portraits and renderings of each person, at rest or active in some way. “Peggy” is one of the first women featured, and for her portrait Ashley gives her face whorls and lines, not dissimilar to those you’d find in wood. This technique is repeated, to varying degrees, with the rest of the people in the book. First the portrait. Then an image of what they do in their daily lives or dreams. The degree of detail in each of these portraits changes a bit. Peggy, for example, is one of the most striking. The colors of her skin, and the care and attention with which each line in her face is painted, make it clear why she was selected to be first. I would have loved the other portraits to contain this level of detail, but the artist is not as consistent in this regard. Charlotte and Dora, for example, are practically line-less, a conscious choice, but a kind of pity since Peggy’s portrait sets you up to think that they’ll all look as richly detailed and textured as she.

The style of the art was also interesting to me. Pen, ink, and watercolors are all Mr. Bryan (who is ninety-two years of age, as of this review) needs to render his people alive. I’ve see him indulge in a range of artistic mediums over the years. In this book, he begins with an image of the estate, an image of the slaves on that estate, and then portraits and renderings of each person, at rest or active in some way. “Peggy” is one of the first women featured, and for her portrait Ashley gives her face whorls and lines, not dissimilar to those you’d find in wood. This technique is repeated, to varying degrees, with the rest of the people in the book. First the portrait. Then an image of what they do in their daily lives or dreams. The degree of detail in each of these portraits changes a bit. Peggy, for example, is one of the most striking. The colors of her skin, and the care and attention with which each line in her face is painted, make it clear why she was selected to be first. I would have loved the other portraits to contain this level of detail, but the artist is not as consistent in this regard. Charlotte and Dora, for example, are practically line-less, a conscious choice, but a kind of pity since Peggy’s portrait sets you up to think that they’ll all look as richly detailed and textured as she.

Those old photographs I once collected may well be the only record those people left of themselves on this earth, aside from a name in a family tree and perhaps on a headstone somewhere. So much time has passed since July 5, 1828 that it is impossible to say whether or not the names on Ashley’s acquired Appraisement are remembered by their descendants. Do families still talk about Jane or Qush? Is this piece of paper the only part of them that remains in the world? It may not have been the lives they led, but Ashley Bryan does everything within his own personal capacity to keep these names and these people alive, if just for a little longer. Along the way he makes it clear to kids that slaves weren’t simply an unfortunate mass of bodies. They were architects and artists and musicians. They were good and bad and human just like the rest of us. Terry Pratchett once wrote that sin is when people treat other people as objects. Ashley treats people as people. And times being what they are, here in the 21st century I’d say that’s a pretty valuable lesson to be teaching our kids today.

On shelves September 13th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Misc: Interested in the other books Mr. Bryan has written or illustrated over the course of his illustrious career? See the full list on his website here.

By:

keilinh,

on 6/27/2016

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Pat Mora,

poems,

natural world,

bilingual,

southwest,

Lee & Low Likes,

Diversity, Race, and Representation,

Add a tag

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year! To recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today and hear from the authors and illustrators.

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year! To recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today and hear from the authors and illustrators.

Today, we’re celebrating one of our favorite poetry titles: Confetti: Poems for Children. This book celebrates the vivid Southwestern landscape of the United States through poems about the natural world. Featuring words from award-winning author Pat Mora and fine artist Enrique O. Sanchez, Confetti is an anthem to the power of a child’s imagination and pride.

Featured title: Confetti: Poems for Children

Featured title: Confetti: Poems for Children

Author: Pat Mora

Illustrator:Enrique O. Sanchez

Synopsis: In this joyful and spirited collection, award-winning poet Pat Mora and fine artist Enrique O. Sanchez celebrate the vivid landscape of the Southwest and the delightful rapport that children share with the natural world.

Awards and honors:

- Children’s Books Mean Business, Children’s Book Council (CBC)

- Choices, Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC)

Other Editions: Did you know that Confetti: Poems for Children also comes in a Spanish edition?

Confeti: Poemas para niños

Purchase a copy of Confetti: Poems for Children here.

Resources for teaching with Confetti: Poems for Children:

Other Recommended Picture Books for Teaching About Poetry:

Water Rolls, Water Rises/El agua rueda, el agua sube, by Pat Mora, illus. by Meilo So

Lend a Hand: Poems About Giving by John Frank, illus. by London Ladd

The Palm of My Heart: Poetry by African American Children, by Davida Adedjoua, illus. by R. Gregory Christie

In Daddy’s Arms I Am Tall: African Americans Celebrating Fathers, by various poets, illus. by Javaka Steptoe

Have you used Confetti: Poems for Children? Let us know!

Celebrate with us! Check out our 25 Years Anniversary Collection.

By:

Becky Laney,

on 6/26/2016

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

Nonfiction,

short stories,

J Fiction,

vintage,

children's classic,

book I bought,

1960,

books reviewed in 2016,

charity book,

Add a tag

Best in Children's Books, Volume 31. 1960. Nelson Doubleday. 160 pages. [Source: Bought]

Let's go vintage! This title is the thirty-first volume in a long series of books called Best in Children's Books. It was published in 1960 by Nelson Doubleday. It blends fiction and nonfiction, prose and poetry. It has many contributing authors and illustrators.

Lewis and Clark: Explorers of the Far West by Smith Burnham with illustrations by Edward Shenton. This is an excerpt from Hero Tales from History (1922, 1930, 1938). If there is a politically incorrect buzzword related to Native Americans--this story has it in abundance: savage, powwow, red men, peace-smoke talk, redskins, red braves, war dance, peace dance, scalp dance, snake dance, papoose, etc. There are better stories of Lewis and Clark to share with young readers these days.

Tattercoats by Joseph Jacobs with illustrations by Colleen Browning. This little story reads like a fairy tale. It even has a little romance.

Singh Rajah and the Cunning Little Jackals by Mary Frere with illustrations by Edy Legrand. This is an excerpt from Old Deccan Days or Hindoo Fairy Legends Current in Southern India (1898). This is an animal story about a LION who is tricked by a family of jackals who don't want to be eaten--they are the last animals in the jungle. What I like best about this story are the color illustrations.

The Middle Bear by Eleanor Estes with illustrations by Phyllis Rowand. This is an excerpt from The Middle Moffat (1942). The Moffats are in a play for charity. The play is The Three Little Bears. It's quite charming.

Chips, The Story of a Cocker Spaniel (1944) by Diana Thorne and Connie Moran with illustrations by Phoebe Erickson. This is a sweet though predictable story of boy meets dog.

The Picnic Basket by Margery Clark with illustrations by Maud and Miska Petersham (1924). This is an excerpt from The Poppy Seed Cakes. This one is illustrated in color. And the illustrations are very interesting--bright and colorful. If you enjoy vintage work, then these illustrations will prove appealing. The story itself is about a boy and his Auntie going on a picnic together. There are plenty of twists and turns in this one!

Windy Wash Day and Other Poems by Dorothy Aldis with illustrations by MAURICE SENDAK. The poems come from All Together (1925, 1926, 1934, 1939, 1952). I like the inclusion of poetry. I really like the poem "Naughty Soap Song."

Just when I'm ready to

Start on my ears,

That is the time that my

Soap disappears.

It jumps from my fingers and

Slithers and slides

Down to the end of the

Tub, where it hides.

And acts in a most diso-

Bedient way

AND THAT'S WHY MY SOAP'S GROWING

THINNER EACH DAY. (86)

Go Fly a Kite is a nonfiction piece by Harry Edward Neal with illustrations by Harvey Weiss. I found it boring, you may find it instructional.

Salt Water "Zoos" is another nonfiction piece. No author is given credit. It is essentially about large aquariums and oceanariums. (This book was published several years before the first Sea World opened. My guess is it used to be a lot harder to see dolphins and sharks and the like.) The focus is on Marineland of Florida.

Cornelia's Jewels by James Baldwin with illustrations by Don Freeman. This one is short and historical in nature. The overall tone is very sweet with a focus on family. Cornelia's "jewels" are her two boys.

Three Seeds by Hester Hawkes with illustrations by Hildegarde Woodward (1956). This story is about a boy and his garden. The setting: the Philippines. Luis, the hero, misses his father who works in Manila most of the time. He can only come visit his family once or twice a month. One week he brings home a package of American seeds. The packet must have had a hole, however, because only three seeds remain. (The title spoils it all doesn't it?) The boy has hope, however, and with the help of a kind neighbor, the three seeds are planted...and from those three seeds comes a promising future.

Let's Go to Iceland and Greenland. This is a sad little feature, again no author is given. Readers do get five photographs and one map.

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

My last post was about some of the reflections that I want to remember when I teach any genre of writing, but I also wanted to share more of our poetry workshop and… Continue reading →

You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen

by Carole Boston Weatherford

illustrated by Jeffrey Boston Weatherford

Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2016

Grades 5-12

Carole Boston Weatherford is one of my favorite poets and authors of books for children. Her picture book, Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement won many awards and praises last year including a 2016 Sibert

Three important reflections inspired by teaching poetry to fifth-grade writers

“A

celebration of the senses on the sand and by the shore.” That’s how a Kirkus reviewer describes the success of

children’s author and poet Kelly Ramsdell

Fineman’s first picture book, At the

Boardwalk. “The oceanside boardwalk bustles

from dawn's first light until night's starry skies.”

This kind of praise isn’t a

surprise to anyone who has read Fineman’s poems, many of which celebrate the

By:

Becky Laney,

on 6/11/2016

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

Nonfiction,

short stories,

vintage,

children's classic,

1958,

book I bought,

charity book,

Nelson Doubleday,

Add a tag

Best In Children's Books. Volume 6. 1958. Nelson Doubleday. 160 pages. [Source: Bought]

Let's go vintage! This title is the sixth volume in a long series of books called Best in Children's Books. It was published in 1958 by Nelson Doubleday. It blends fiction and nonfiction, prose and poetry. It has many contributing authors and illustrators.

The Story of Early America by Donald Culross Peattie, illustrated by Leonard Weisgard. This is an excerpt from A Child's Story of the World (1937). Honestly, I think I enjoyed the illustrations more than the text. Readers should know two things 1) These two chapters do not hold up to the test of time. They didn't age gracefully, in other words. 2) They contain passages with the potential to offend in varying degrees.

When Columbus landed, some naked red men on the shore ran away. After a while their childish curiosity got the better of them, and they came stealing out to meet the newcomers. (10)

He saw that these people were much more simple-minded than criminals from the jails of Spain. (11)

They were so evidently savages, and not the rich, civilized people that he expected to meet in India. So he called these men Indians, and so they have been called ever since, though of course our redskins have nothing to do with the real people of India. (11)

So the Spanish, Portuguese, and English sent ships to Africa to capture the jungle Negroes. They were thrown into boats and brought to America. The Negroes had powerful bodies. They did not mind the intense heat. They were afraid of the white men, and knew that they could never escape back across the sea. So they bent their backs to the hard labor and tried to be cheerful. They made good slaves. (23)

In the northern states slavery soon died out. One reason for this was that, in the North, factories and not farming were the important way of making money. Intelligent men were needed to work in factories. The Negroes, fresh from jungle life, were not ready for such work. But in the South, where tobacco, cotton, and rice were rich crops which all the world was clamoring to buy, the Negro slave could work better than the free white man. He did not have to use his head, but only his muscles. (31-2)

The Very Little Girl (1953) is by Phyllis Krasilovsky and illustrated by Ninon. This is a charming, delightful, very unoffensive little piece about a little girl who slowly but surely finds herself growing up.

The Elephant's Child (1900) by Rudyard Kipling. Illustrated by Henry C. Pitz. I LOVE, LOVE, LOVE, LOVE, LOVE, LOVE, LOVE this one. This is probably one of the main reasons I bought this book. In this story, readers learn about how the elephant got his trunk. A lot of spanking is involved! And the Elephant's Child isn't only the recipient of the spanking. This one makes a GREAT read aloud. While I would never, ever, ever read aloud The Story of Early America, I would share The Elephant's Child. Kipling has a way with words. "Great, grey-green, greasy Limpopo River." I enjoy the characters. Especially the elephant, the crocodile, and the snake.

Poems of the City (1924) by Rachel Field, illustrated by Harvey Weiss. A selection of eleven poems by Rachel Field. Poems include "Skyscrapers," "Good Green Bus," "The Pretzel Man," "The Ice-Cream Man," "The Stay-Ashores," "The Animal Store," "City Rain, "Pushcart Row," "Chestnut Stands," "Taxis," and "At the Bank." My favorite was "The Ice-Cream Man."

The next story is The Shoemaker and The Elves by Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm illustrated by Fritz Kredel. This is the traditional story. The illustrations are something. And it is an illustration from this story that is on the cover of this book.

A Child's World in ABC by Mary Warner Eaton, illustrated by Charlotte Steiner. This piece was written specifically for this book. I liked this one well enough. I liked the illustrations especially. But that doesn't mean it aged well.

Your Breakfast Egg is by Benjamin C. Gruenberg and Leone Adelson. Illustrated by Leonard Kessler. This was first published in 1954. It is an excerpt from YOUR BREAKFAST AND THE PEOPLE WHO MADE IT. Essentially it is a nonfiction piece celebrating "modern" and "scientific" advances in how chickens are kept, raised, etc. Celebrate the fact that your hens no longer have to go outside and find their own food to eat! Rejoice that now--day and night--they are kept inside cages and are fed with "all kinds of grains and other foods that are good for them." This chapter made me shudder. I had read about this in The Dorito Effect, of course, as one of the many illustrations of what is wrong with food. But this is a period-piece, if you will, showing how silly we can be.

Life in the Arctic and This is Italy are short nonfiction pieces with no given author. Both include a few photographs.

The Saddler's Horse by Margery Williams Bianco, illustrated by Grace Paull, is a short story about a saddler's horse and a cigar-store wooden Indian having a runaway adventure together.

Dick Whittington and His Cat is adapted from James Baldwin and illustrated by Peter Spier. I read a picture book by Marcia Brown (1950) last year and really enjoyed it. This story is nice, nothing unexpected, but nice.

Concluding Thoughts: The book is "flawed" in some ways in that a few of the pieces in this one reveal an America with a very different value system. But it's an opportunity to celebrate how far we've come in understanding one another as well. Some pieces sit "heavy" and others are just very light delights.

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

This month's image comes from Tanita Davis, who photographed this magnificent sculpture of a harpy at the Kelvingrove Museum in Scotland.

|

| "The Harpy Celaeno," by Mary Pownall Bromet* |

Her name is Celaeno, which means "storm-cloud," as the harpies were originally that: female weather spirits. Later, they became known as agents of justice and revenge, often with an ugly streak and potent stench, but I see no foulness here---only focused power. Power that challenged me to do it justice.

It took me several tries to meet her challenge. At first, I wrote this creature a free verse poem, but she was having none of that. Choose a form! she cried. Let me breathe my fury into a known shape, like wind into sails! Chastised, I began again, this time with the repeating, swirling lines of a pantoum to guide me. I got lost, several times, but she steered me true to the end.

I'm particularly happy with the title. Women, unlike winds, are "nor fair, nor foul" as legends try to make us. Why not just be magnificent?

Nor fair nor foul(a Pantoum for Harpies everywhere)

In her naked marbleness she’s stern knots,

even to her stomach’s creases—She’s a woman

-tall instrument, stroking a blood tune from

wrong-doers. Celaeno wrings life from life;

Even to her stomach’s creases—she’s a woman.

With wings close to her ears, furiously beating

wrong-doers, Celaeno wrings life; from life she

tears justice; squeezes her breast until it cries milk;

With wings close to her ears, furiously beating

clouds, fingernails like tractor screws, she harps

tears. Justice squeezes her breast until it cries. Milk

and honey people the earth but women are storm

clouds. Fingernails like tractor screws, they harp

at naked marble. They’re stern, not

honey, they people the earth. Women are storm

instruments, stroking a blood tune.

----Sara Lewis Holmes

My poetry sisters also wrote to this image, and yowza! We stirred up some powerful poems:

LauraLiz

TanitaAndi

TriciaKellyPoetry Friday is hosted today by Jone at

Check It Out.

*Tanita passed along the following information about the artist:

Mary Pownall Bromet was an English-born Lancashire lass, b. 1890, d. 1937. She was a pupil of the great Rodin, and studied with him for four years around 1900... Much of her work ended up in private collections, or smaller British galleries so there's not much record online. She was known for her technical prowess (which netted her the Watford War Memorial job) and was commissioned to do a great many bodies/faces.

Hypertrophic Literary (AL) is open to submissions for upcoming issues. Looking for pieces that evoke a physical reaction, make readers feel something: joy, nausea, shock, desperation. Open to submissions of poetry, fiction, excerpts, and nonfiction. Hypertrophic accepts work in all genres and “[doesn’t] care who you are, if you’ve been published before, if it’s your first book or seventy-fourth.”

Hypertrophic Literary (AL) is open to submissions for upcoming issues. Looking for pieces that evoke a physical reaction, make readers feel something: joy, nausea, shock, desperation. Open to submissions of poetry, fiction, excerpts, and nonfiction. Hypertrophic accepts work in all genres and “[doesn’t] care who you are, if you’ve been published before, if it’s your first book or seventy-fourth.”

Rescue Press invites entries for the Black Box Poetry Prize, a contest for full-length collections of poetry. Open to poets at any stage in their writing careers. Judge: Douglas Kearney. No reading fee; however donations are appreciated and go toward publishing the winning manuscript(s). Authors who donate $15 or more receive a Rescue Press book of their choice. Deadline: June 30, 2016.

Rescue Press invites entries for the Black Box Poetry Prize, a contest for full-length collections of poetry. Open to poets at any stage in their writing careers. Judge: Douglas Kearney. No reading fee; however donations are appreciated and go toward publishing the winning manuscript(s). Authors who donate $15 or more receive a Rescue Press book of their choice. Deadline: June 30, 2016.

Twitter: @rescuepress.co

The University of Toronto’s speculative fiction journal, The Spectatorial, is currently looking for fiction, poetry, articles, essays, graphic fiction, novel excerpts, book/movie reviews, etc. Particularly interested in topics that touch upon other cultures and marginalized groups, whether it’s discussing literature no one has heard of from another country, or addressing social justice issue in a speculative work. Articles 500-1200 words, or pitched proposals for topics of interest. Deadline: ongoing.

The University of Toronto’s speculative fiction journal, The Spectatorial, is currently looking for fiction, poetry, articles, essays, graphic fiction, novel excerpts, book/movie reviews, etc. Particularly interested in topics that touch upon other cultures and marginalized groups, whether it’s discussing literature no one has heard of from another country, or addressing social justice issue in a speculative work. Articles 500-1200 words, or pitched proposals for topics of interest. Deadline: ongoing.

Mentorship model literary press The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective invites entries for the Emerging Poets Prize & Editor’s Choice Award. The prize aims to help nurture and bring out new poetic voices from India and the Indian diaspora and those that have a meaningful connection to India. Up to three manuscripts chosen for publication. Winners receive Rs. 15,000 (or equivalent in local currency), publication (minimum press run of 250), and 20 author copies, plus membership. Manuscripts must be in English. No translations. Deadline: May 30, 2016.

Mentorship model literary press The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective invites entries for the Emerging Poets Prize & Editor’s Choice Award. The prize aims to help nurture and bring out new poetic voices from India and the Indian diaspora and those that have a meaningful connection to India. Up to three manuscripts chosen for publication. Winners receive Rs. 15,000 (or equivalent in local currency), publication (minimum press run of 250), and 20 author copies, plus membership. Manuscripts must be in English. No translations. Deadline: May 30, 2016.

The Eden Mills Literary Contest is open for entries from new, aspiring and modestly published writers 16+. Categories: short story (2500 words max.), poetry (five poems max.). and creative nonfiction (2500 words max.) First prize in each category: $250. Winners invited to read a short selection from their work at the festival on Sunday, September 18, 2016. Entry fee: $15. Deadline: June 30, 2016.

PRISM International invites entries for the inaugural Pacific Spirit Poetry Prize. First prize: $1500 grand prize ($600 runner-up, $400 2nd runner-up. Up to three poems per entry (100 lines max per poem). Entry fees: $35-$45 (includes subscription). Deadline: October 15, 2016.

PRISM International invites entries for the inaugural Pacific Spirit Poetry Prize. First prize: $1500 grand prize ($600 runner-up, $400 2nd runner-up. Up to three poems per entry (100 lines max per poem). Entry fees: $35-$45 (includes subscription). Deadline: October 15, 2016.

Children’s publisher Annick Press (Canada) is seeking true stories of bravest moments for a YA non-fiction anthology. The format of the testimonial can be in one of many different mediums (prose, poetry, photography, illustration, etc.). Contact Robbie Patterson at [email protected] for full details.

Children’s publisher Annick Press (Canada) is seeking true stories of bravest moments for a YA non-fiction anthology. The format of the testimonial can be in one of many different mediums (prose, poetry, photography, illustration, etc.). Contact Robbie Patterson at [email protected] for full details.

The Cossack Review is looking for submissions of poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, flash fiction and works in translation for their next print and online issues. Send 3-6 poems, one story, or one essay. Especially interested in thoughtful, diverse work.

The Cossack Review is looking for submissions of poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, flash fiction and works in translation for their next print and online issues. Send 3-6 poems, one story, or one essay. Especially interested in thoughtful, diverse work.

Many of my students are drawn to realistic fiction because it gives them a chance to immerse themselves in someone else's story. In fact, a recent study has shown that reading literary fiction helps improve readers' ability to understand what others are thinking and feeling (see this article in Scientific American).

Laura Shovan's novel in verse, The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary, is full of distinct voices that prompt us to think about different students' unique perspectives. It's one my students are enthusiastically recommending to one another.

The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary

by Laura Shovan

Wendy Lamb / Random House, 2016

Google Books preview

Your local library

Amazon

ages 9-12

*best new book*

Eighteen fifth graders keep poetry notebooks chronicling their year, letting readers peak into their thoughts, hopes and worries as the year progresses. Fifth grade is a momentous year for many students, as the finish elementary school and look ahead to all the changes that middle school brings. This year is particularly full of impending change for Ms. Hill's class because their school will be demolished at the end of the year to make way for a new supermarket.

Through these short poems, Shovan captures the distinct, unique voices of each student. The class is diverse in many ways--racially, ethnically, economically, and more. At first, I wondered if I would really get to know the different students since each page focused on a different child; however, as the story developed, I really did get a sense of each individual as well as the class as a whole. Shovan creates eighteen distinctive individuals--with personalities and backgrounds that we can relate to and envision. And these experiences shape how each individual reacts to the year.

I particularly love novels in verse because they allow readers a chance to see inside character's thoughts without bogging the narrative down in too much description. As researcher David Kidd said (in this

Scientific American article), literary fiction prompts readers to think about characters: "we’re forced to fill in the gaps to understand their intentions and motivations.” This is exactly what ends up being the strength of Laura Shovan's novel.

The funniest thing, for me personally, has been the shocked look of many of my students when I show them this cover. You see, our school is called Emerson Elementary School. "This is a real book?!?!" they say, incredulously. I know my students will particularly like the way these students protest the plans to demolish their school, bringing their protest to the school board.

As you can see in this

preview on Google Books, this collection of poems slowly builds so readers get a sense of each student in Ms. Hill's fifth grade. The poetry feels authentic, never outshining what a fifth grader might write but always revealing what a fifth grader might really be thinking.

I highly recommend the audiobook for

The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary. The diverse cast of Recorded Books brings alive each character. This would make a great summer listen, or a great read-aloud for the beginning of the school year.

The review copy for the audiobook was purchased from Audible and for the print copy it was borrowed from my local library. If you make a purchase using the Amazon links on this site, a small portion goes to Great Kid Books. Thank you for your support.

©2016 Mary Ann Scheuer, Great Kid Books

By: Helena Palmer,

on 5/22/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Poetry,

Literature,

love,

Religion,

literary theory,

christianity,

theology,

Song of Solomon,

*Featured,

Religious Poetry,

religious studies,

christian theology,

Arts & Humanities,

Christian Poetry,

Song of Songs,

Add a tag

hy were Christian theologians in the ancient and medieval worlds so fascinated by a text whose main theme was erotic love? The very fact that the 'Song of Songs', a biblical love poem that makes no reference to God or to Israelite religion, played an important role in pre-modern Christian discourse may seem surprising to those of us in the modern world.

The post Christian theology, literary theory, and sexuality in the ‘Song of Songs’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Making space for poetry.

View Next 25 Posts

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year and to recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today as well, as hear from the authors and illustrators.

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year and to recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today as well, as hear from the authors and illustrators.

How have you used

How have you used

Rescue Press invites entries for the

Rescue Press invites entries for the  The University of Toronto’s speculative fiction journal,

The University of Toronto’s speculative fiction journal,  Mentorship model literary press

Mentorship model literary press  PRISM International invites entries for the inaugural

PRISM International invites entries for the inaugural  Children’s publisher

Children’s publisher

I like poems. Thanks for sharing. Online News Publish