new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Alfred Hitchcock, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 11 of 11

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Alfred Hitchcock in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 2/21/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Biography,

wireless,

British,

British Library,

DNB,

Alfred Hitchcock,

odnb,

florence nightingale,

arthur conan doyle,

British history,

*Featured,

Audio & Podcasts,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

Desert Island Discs,

Online products,

oxford dictionary national biography,

Herbert Asquith,

King George V,

christabel pankhurst,

tom denning,

vidal sassoon,

Add a tag

For 135 years the Dictionary of National Biography has been the national record of noteworthy men and women who’ve shaped the British past. Today’s Dictionary retains many attributes of its Victorian predecessor, not least a focus on concise and balanced accounts of individuals from all walks of national history. But there have also been changes in how these life stories are encapsulated and conveyed.

The post Let the people speak: history with voices appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Charley,

on 8/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

critical flicker-fusion frequency,

frame rate,

illusion of motion,

Lumière Brothers,

optical illusion,

psychology of music in multimedia,

Siu-Lan Tan,

visual processsing,

Books,

film,

Alfred Hitchcock,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Science & Medicine,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

Films trick our senses in many ways. Most fundamentally, there’s the illusion of motion as “moving pictures” don’t really move at all. Static images shown at a rate of 24 frames per second can give the semblance of motion. Slower frame rates tend to make movements appear choppy or jittery. But film advancing at about 24 frames per second gives us a sufficient impression of fluid motion.

However, birds–such as pigeons–have a much higher threshold for detecting movement. A bird’s visual system is keenly sensitive to moving stimuli as this is essential to their survival. Whether swooping down to snatch live prey, fleeing from a predator, or zeroing in on a nest for a precise landing, birds must rely on their fine-tuned ability to hone in on moving targets. So the frame rate at which most of our films are shown is far too slow for birds to perceive continuous motion. Their threshold of visual processing exceeds the standard frame rate, allowing them to see component frames … and the illusion of motion pictures would be broken.

If a pigeon had been roosting in the theater where 19th century crowds first gaped at the Lumière Brothers’ steam train looming towards them, it may have been less than impressed — especially as early silent films were often played at only 16 frames per second.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even a film shown at today’s industry standard of 24 frames per second would most likely look like a series of flashing slides to a pigeon. We’re mesmerized by Marilyn Monroe’s white skirts billowing over the subway grate in The Seven-Year Itch, but a pigeon may see something more like a slide show of the skirt in frozen increments.

Further, most humans cannot distinguish individual lights flashed at 60 cycles per second, perceiving instead a single continuous beam of light. This gives an impression of constant light while watching a film (despite the shutter actually shutting out light several times per frame). But birds have much higher critical flicker-fusion frequency, such as 90-100 cycles per second or higher (e.g., Lisney et al., 2011). So while humans do not perceive the flicker in a movie, a pigeon may see flashes like strobelights along with the jumpy frames of Marilyn’s airborne skirt.

One of the creepiest scenes in Hitchcock’s The Birds shows Melanie (Tippi Hedren) smoking on a bench in a school playground while birds are flocking on a jungle gym behind her. She finally spots a lone bird flying overhead and turns around to discover every rung of the jungle gym crowded with large black birds. Actually, Hitchcock used cardboard cut-outs for most of the “birds” on the jungle gym, figuring that most people would not notice these stationary objects if interspersed with live birds.

Birds in a school playground in Hitchcock’s (1964) The Birds

Indeed, the illusion works on most of us. We are also often tricked by illusory “crowds” in films–made of real people and dummies, or multiple images of the same people patched together to make a “crowd”. However birds are especially observant of the movement of other birds–and combined with the much faster ‘refresh rate’ of the avian visual system (as their visual information is “updated” more frequently than humans)–the jungle gym scene would not likely fool any birds.

Studies suggest that birds do perceive some information via video images (using video at 30 frames per second). For instance, a video of wild chickens feeding elicits feeding in birds of the same species (McQuoid & Galef, 1993); videos showing a hawk or raccoon elicit aerial and ground alarm calls respectively in roosters (Evans, Evans, and Marler, 1993); and video images of female pigeons elicit courtship displays in male pigeons (Shimizu, 1998).

So birds seem to pick up some information from video images, at a somewhat higher frame rate and screen-refresh rate than film–though color may be distorted (Wright & Cumming, 1971), and gaps in movement and flicker are likely perceived (Lea & Dittrich, 1999). These discrepancies would be much more pronounced for moving images on cinematic film.

A fine-tuned visual system gives birds of prey an advantage when pursuing a fast-moving target. And it allows pigeons those few extra seconds to peck at grubs and seeds–and flap away at the last moment possible when your car approaches.

Nut their super-efficient processing of moving stimuli would make the cinematic experience as we know it less than spellbinding for the birds.

In conclusion: it’s interesting to note that film relies on certain limitations or imperfections of the human perceptual system for its magic to work!

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why you can’t take a pigeon to the movies appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Jerry Beck,

on 5/2/2013

Blog:

Cartoon Brew

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Disney,

Animators,

Walt Disney,

Mickey Mouse,

Alfred Hitchcock,

Ub Iwerks,

The Birds,

Iwerks Studio,

Plane Crazy,

The Skeleton Dance,

Add a tag

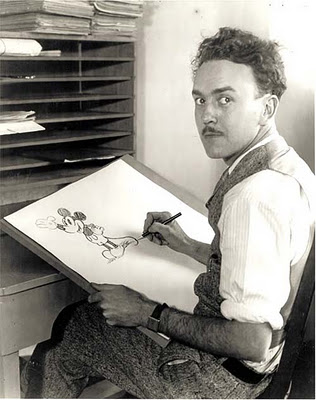

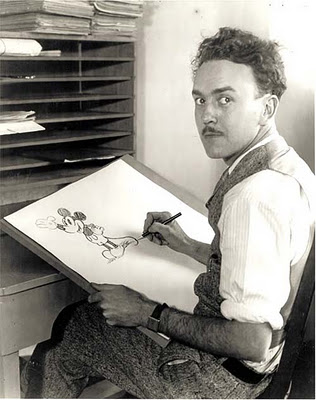

Most animation fans know that Ub Iwerks co-created Mickey Mouse. But he contributed a lot more to animation than people think.

1. Ub Iwerks was a workhorse

While the rest of Disney’s studio was toiling away on the last few “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” shorts that they were contractually obligated to finish for Universal, Ub animated the first Mickey Mouse cartoon, Plane Crazy, alone and in complete secrecy. During work hours, Ub would place dummy drawings of Oswald on top of his Mickey drawings so nobody would know what he was doing. At night, Ub would stay late and animate on Mickey. He animated the entire six-minute short singlehandedly in just a few weeks, reportedly averaging between 600-700 drawings a night, an astounding feat that hasn’t been matched since. When the success of Mickey Mouse propelled the Disney studio to new heights, Ub continued his efficient streak by animating extensive footage on Silly Symphonies shorts like The Skeleton Dance and Hell’s Bells.

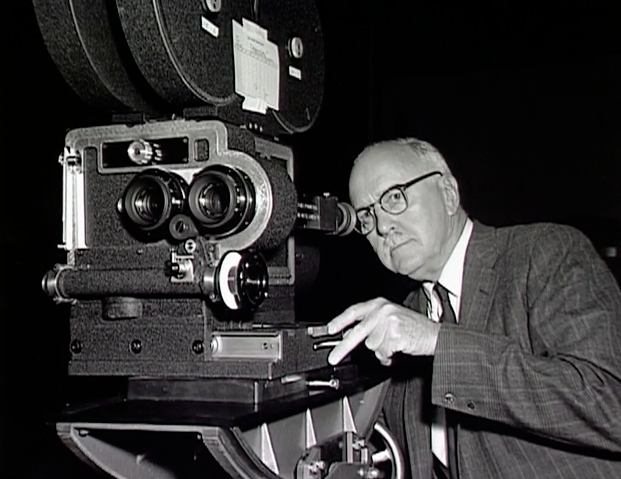

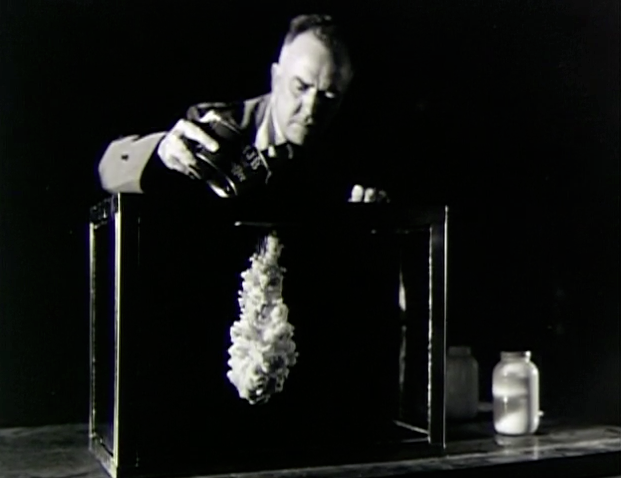

2. Ub Iwerks was a mechanical marvel

When not animating with a pencil, Ub loved to build and create inventions. He was intrigued by the inner workings and mechanics of machines, and loved to delve into what made things work. Supposedly he once dismantled his car and reassembled it over the course of a weekend. With this mechanical knowhow, Ub invented devices that incorporated new techniques into his cartoons. After Iwerks opened the Iwerks Studio in 1930, he heard that Disney was attempting to develop what later became the multiplane camera. Ub one-upped his old partner and made his own version from car parts and scrap metal, and incorporated the multilane technique into his cartoons, like The Valiant Tailor:

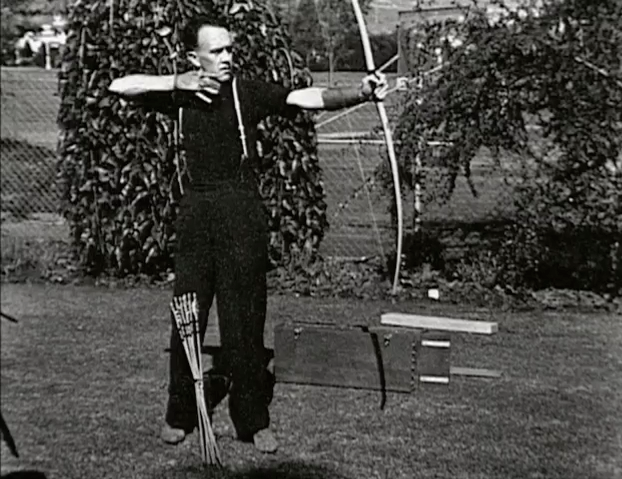

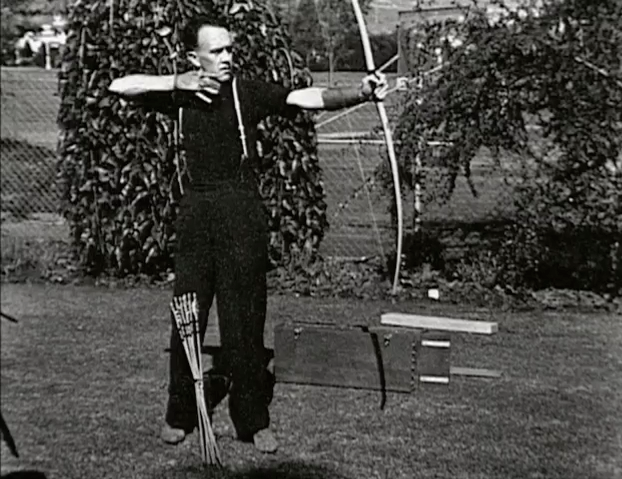

3. Ub Iwerks was a jack of all trades, and a master of every one

Besides being a skilled animator, mechanic and machinist, Ub constantly expanded his creative and intellectual pursuits through hobbies and sports. Being the ultimate challenge-seeker, he excelled at every single thing he attempted. And when he felt that he had mastered something and it was no longer a challenge to him, he’d quit. When Ub bowled a perfect 300 game, he put his bowling ball in the closet and never bowled again. When he took up archery, he became such a skilled archer that he got bored of getting bulls-eyes and quit that too. Even as an animator, Ub felt he perfected his craft and after his studio closed in the mid-1930s, he never animated again.

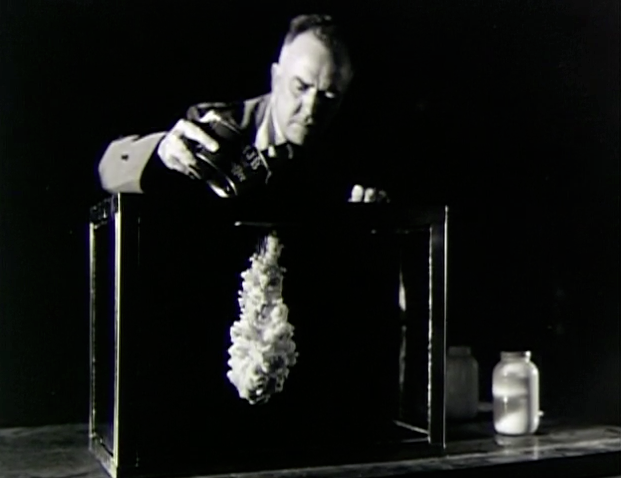

4. Ub Iwerks created movie magic

When Ub rejoined the Disney studio in 1940, Walt Disney gave his old partner free reign to do as he wished. With Disney’s resources, Ub developed special effects techniques for animation, live-action films and Disney’s theme parks, much of which is still in use today. He helped develop the sodium vapor process for live-action/animation combination and traveling mattes, which he won an Oscar for in 1965 after utilizing it in Mary Poppins. He adapted the Xerox process for animation, which eliminated the tedious task of hand inking every cel. For Disneyland, Ub designed and developed concepts for many of the park’s attractions, including the illusions in The Haunted Mansion and the animatronics for attractions like Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln and Pirates of the Caribbean. Disney even loaned him out to Alfred Hitchcock to help with the effects needed to create flocks of attacking birds in The Birds.

5. Ub Iwerks made animation what it is today

If Winsor McCay laid he foundation for character animation, then Ub Iwerks built a castle on top of it. He took the didactic rigidness of what animation was in his era and made it loose, organic, appealing and fun. Building upon what Otto Messmer did before him with Felix the Cat, the characters Ub animated were packed with personality. Characters like Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse were creations that audiences could relate to as no characters before. They thought, breathed, emoted and were infused with life.

What Iwerks designed and animated in shorts like Steamboat Willie and Skeleton Dance contained the principles (squash and stretch, appeal, anticipation, etc.) that became the genesis of the “Disney style”, which animators like Fred Moore and Milt Kahl later fleshed out. His work reached out and influenced animators all over the world, and they took the ball and ran with it. Rudolph Ising and Hugh Harman, who worked under Ub at Disney, brought his sensibilities to Warner Bros. and developed the Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes series. Many animators got their start at Ub’s studio in the early 30′s, including UPA co-founder Steve Bosustow and Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones. Manga and anime pioneer Osama Tezuka was also greatly influenced and inspired by Ub’s work.

To learn more about Iwerks’ life and work, read the biography The Hand Behind the Mouse .

.

By: Alice,

on 2/21/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oscars,

Charlie Chaplin,

Helen Mirren,

Audrey Hepburn,

Alfred Hitchcock,

odnb,

stanley kubrick,

George Bernard Shaw,

Cary Grant,

Laurence Olivier,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

oxford dnb,

who's who,

Arts & Leisure,

Online Products,

Vivien Leigh,

>Elizabeth Haffenden,

Alec Guinness,

Anthony Minghella,

Carol Reed,

Colin Welland,

David Lean,

Jack Clayton,

Jessica Tandy,

John Osborne,

History,

Biography,

Add a tag

In his acceptance speech at the 1981 Oscars (best original screenplay, Chariots of Fire), Colin Welland offered the now famous prediction that ‘The British are coming!’ There have since been some notable British Oscar successes: Jessica Tandy for Driving Miss Daisy (1989); director Anthony Minghella for The English Patient (1996); Helen Mirren (in The Queen, 2006); and — maintaining the royal theme — awards for best director, actor, and film for The King’s Speech in 2011.

But looking at all British Oscar winners — since the first Academy Awards in 1929 — presents a different story. Less the ‘British are coming!’, more the ‘British have been!’ A full list of Oscar winners with entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (currently 79 individuals) lists 70 recipients between 1929 (Charlie Chaplin, The Circus) and 1980 (Alec Guinness, honorary award), and just 9 winners since Colin Welland’s rousing prediction. The Oxford DNB’s selection criteria — that all people included are deceased in or before 2009 — means this imbalance isn’t really a revelation, nor should it come as a surprise. Quite simply, and happily, most post-1981 British winners remain in good, creative health.

But the ODNB’s Oscar list is nonetheless an interesting reminder of outstanding talent, and outstanding films, from the history of British cinema. Here, of course, you’ll find the great names: Vivien Leigh (twice best actress for Gone with the Wind, 1940, and A Street Car Named Desire, 1952), Laurence Olivier (special award for Henry V, 1947 and best actor, Hamlet, 1949), or the lovely Audrey Hepburn (best actress, Roman Holiday, 1954). Also notable is that some of the most successful figures in British cinema have worked behind the camera, including the directors Carol Reed and David Lean who were both double winners.

The Oxford DNB’s list also reminds us of the perhaps forgotten successes: Jack Clayton whose The Bespoke Overcoat won ‘best short (two-reel) film’ in 1957 or Elizabeth Haffenden, winner, in 1960, of the best costume (colour) Oscar for the often scantily-clad Ben-Hur. Then there are the surprises: did you know that George Bernard Shaw won a statuette in 1939 for his adapted screenplay of Pygmalion, or that the dramatist John Osborne collected the same award for Tom Jones in 1964?

Finally, there are the ones who almost got away. It seems extraordinary that Stanley Kubrick (he lived in Britain, so he’s in the ODNB) won only once — and this for ‘best special effects’ in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Or that Cary Grant (born in Bristol) had to make do with an ‘honorary award’ in 1970. Perhaps most surprising is that the giant of twentieth-century film, both in the UK and US, only reached the stage once, to receive the Irving G. Thalberg memorial award in 1968. He, of course, is Alfred Hitchcock whose life is recreated in an eponymous film out this month — and possibly on next year’s Oscar shortlist.

In addition to the Oxford DNB biographies above, the life stories of Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant are also available as episodes in the ODNB’s free biography podcast.

Now, from podcast to a pop quiz from Who’s Who, we’ll test you not only on what you know about the BAFTAs and Oscars, but who you know.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. In addition to 58,500 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcastwith over 175 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

Who’s Who is the essential directory of the noteworthy and influential in every area of public life, published worldwide, and written by the entrants themselves. Who’s Who 2013 includes autobiographical information on over 33,000 influential people from all walks of life. The 165th edition includes a foreword by Arianna Huffington on ways technology is rapidly transforming the media.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: CHICAGO – JANUARY 23: Oscar statuettes are displayed during an unveiling of the 50 Oscar statuettes to be awarded at the 76th Academy Awards ceremony January 23, 2004 at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois. The statuettes are made in Chicago by R.S. Owens and Company. (Photo by Tim Boyle) EdStock via iStockphoto.

The post ‘And the Oscar went to …’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kathy Temean,

on 3/25/2012

Blog:

Writing and Illustrating

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Tips,

inspiration,

Advice,

Shakespeare,

Alfred Hitchcock,

Salvador Dali,

Brian Allen Brushwood,

Penn & Teller,

Rouald Dahl,

Add a tag

Magician Brain Brushwood tells a story on his blog about talking to Teller of Penn and Teller and how Teller ended up responding to a letter he wrote when frustrated by his industry. He’s talking magic, but isn’t that what we do, too? I think you will find it good advice for anyone writing a book.

Magician Brain Brushwood tells a story on his blog about talking to Teller of Penn and Teller and how Teller ended up responding to a letter he wrote when frustrated by his industry. He’s talking magic, but isn’t that what we do, too? I think you will find it good advice for anyone writing a book.

Here’s Teller:

Try stuff. Make your best stab and keep stabbing. If it’s there in your heart, it will eventually find its way out. Or you will give up and have a prudent, contented life doing something else.

Surprise me.

That’s it. Place 2 and 2 right in front of my nose, but make me think I’m seeing 5. Then reveal the truth, 4!, and surprise me.

Now, don’t underestimate me, like the rest of the magicians of the world. Don’t fool yourself into thinking that I’ve never seen a set of linking rings before and I’ll be oh-so-stunned because you can “link” them. Bullshit.

Here’s how surprise works. While holding my attention, you withhold basic plot information. Feed it to me little by little. Make me try and figure out what’s going on. Tease me in one direction. Throw in a false ending. Then turn it around and flip me over.

Read Rouald Dahl. Watch the old Alfred Hitchcock episodes. Surprise. Withhold information. Make them say, “What the hell’s he up to? Where’s this going to go?” and don’t give them a clue where it’s going. And when it finally gets there, let it land. An ending.

It took me eight years (are you listening?) EIGHT YEARS to come up with a way of delivering the Miser’s Dream that had surprises and an ENDING.

Love something besides magic, in the arts. Get inspired by a particular poet, film-maker, sculptor, composer. You will never be the first Brian Allen Brushwood of magic if you want to be Penn & Teller. But if you want to be, say, the Salvador Dali of magic, well THERE’S an opening.

I should be a film editor. I’m a magician. And if I’m good, it’s because I should be a film editor. Bach should have written opera or plays. But instead, he worked in eighteenth-century counterpoint. That’s why his counterpoints have so much more point than other contrapuntalists. They have passion and plot. Shakespeare, on the other hand, should have been a musician, writing counterpoint. That’s why his plays stand out from the others through their plot and music.

Here is the link to read the whole letter:

http://shwood.squarespace.com/news/2009/9/21/14-years-ago-the-day-teller-gave-me-the-secret-to-my-career.html

Talk tomorrow,

Kathy

Filed under:

Advice,

inspiration,

Writing Tips Tagged:

Alfred Hitchcock,

Brian Allen Brushwood,

Penn & Teller,

Rouald Dahl,

Salvador Dali,

Shakespeare  1 Comments on Words of Wisdom from Teller (Penn & Teller), last added: 3/26/2012

1 Comments on Words of Wisdom from Teller (Penn & Teller), last added: 3/26/2012

Alfred Hitchcock’s definition of happiness

An eight-year-old named Jake sent me a nice, long letter about my book, Jigsaw Jones #11: The Case of the Marshmallow Monster. He included this fantastic drawing:

As for the letter . . .

I replied, in part:

In real life, there was once a famous movie director named Alfred Hitchcock. His movies were sooo scary. Everybody loved them — because for some strange reason, people LIKE to be scared. That’s why the kids in my story are eager to hear more, more, more.

So when I needed a man to tell a scary story, I modeled him after a real person, Alfred Hitchcock. In the story, you’ll see that he’s known as “Mr. Hitchcock,” and later on Mr. Jordan calls him “Alfred.”

Computer savvy readers — and I’m assuming you are (savvy, that is) — can click here to learn more insider info about that book.

By Robert Kolker

“That’s that,” quoting Ace Rothstein at the end of Casino. I didn’t end the Martin Scorsese chapter on an optimistic note in the fourth edition of A Cinema of Loneliness. There is more than a hint that the Scorsese’s creative energies might be flagging.

My pessimism grew from the direction — or lack of direction — Scorsese’s films had taken over the past decade. I thought that the big productions of the 2000s — Gangs of New York, The Aviator, and The Departed — indicated some kind of flailing about for ideas. These films were not as lean and mean as the earlier gangster movies that worked at the speed of light and were deliriously comic in their basic brutality.

Copyright Paramount Pictures. Source: shutterisland.com.

Shutter Island seemed to seal the decline. An unofficial remake of Samuel Fuller’s 1963 Shock Corridor, the film could have been made, I thought, by anyone. It bore none of the hallmarks of Scorsese’s style and all of the hallmarks of an overwrought Hollywood gothic tale.

An obvious riposte to my pessimism is that I am not in a position to question an artist’s evolution. Scorsese no more than any other filmmaker is bound to repeat himself, and the great gangster and street films of his early period are a thing of the past. Artists change with time, and the results of that change may not be to everyone’s taste. At least not to mine.

With this in mind, I went to see Hugo with a lot of skepticism. Why would Scorsese make a film in 3D? The only reason I could come up with — aside from the fact that he might just wish to experiment with the old/new screen technology of the moment — is that Alfred Hitchcock made a 3D film when that format was first introduced in the 1950s: Dial M For Murder. Scorsese almost always roots his work in films of the past. His imagination is constructed of film. He is an amateur archivist, with a huge collection of movies that he watches continually. He has his cast and crew look at old movies when they are preparing a new one. His films become something of archival works themselves, full of allusions to their predecessors. But there is more to it than this.

I have resisted the recent 3D craze. I did go to see Avatar out of curiosity. James Cameron does not often repay curiosity. But something stood out in that film. The mise-en-scène of Cameron’s mythical world, with its floating vegetation in a liquid like atmosphere, reminded me of the underwater sequences of Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (Le voyage dans la lune, 1902). This magical film — Méliès was a magician as well as a filmmaker — was just one entry into his enormous filmography of fantasy filmmaking, his counter to the

Alfred Hitchcock earned many names in his time as a filmmaker, including The Master of Suspense.

Suspense is vital to most writing--every story depends on at least a little emotional tension or there is no story. (Thumb your nose, guardians of the avant-garde.) Horror, thriller, and mystery fiction relies on suspense.

I showed my classes this wonderful clip from The Birds. While Rear Window, North by Northwest, and Psycho may have been better films from start to finish, this snippet reveals Hitchcock's masterful touch (and is pretty damn creepy, as well).

Suspense is all about waiting. You know something bad is going to happen, but the master makes you wait for it.

This post is the result of two different conversations with two different friends that I've had in the past few months. In conversation one; my friend said to me that one of the best ways to solve your own problems in life is to find somebody else, give them advice, and then follow it yourself. I don't doubt that he was talking about me to me.

In conversation two my friend and I were talking about our personal voice in illustration, I recommended to her that she take a closer look at the work that inspires and influences her, and examine them for all the qualities that she liked. In other words, the "why," as in "Why do you like that piece of art?" In doing this that she would be able to see the continuous thread that ran through all these disparate images, and that thread would be her personal preferences, her aspirations. Expanding out from there, she would be able to strengthen her own works by explicitly understanding her influences. Simple, right?

So, you see, this post is me, taking my own advice, and hauling some art into the light, expressing my perceptions of them in an effort to reveal qualities which I endeavor to imbue in future illustrations.

Mood and Tone; The concept

Two artists who are wonderful in the conveyance of Mood and Tone are John Jude Palencar and Alfred Hitchcock. Both of whom are able to create intense, and sometimes somber, moods in their works. I've been a fan of John Jude Palencar's work for quite some time, however it is rarely the subject matter he chooses which captivates me, but it is the way he portrays things, his technique, pallet, and composition. Which add up to the creation of specific moods through out his work. So, it is his use of the tools at hand which he chooses to express himself that I admire.

Because John Jude Palencar's expressions are often psychologically charged, that, I thought a nice companion artist would be Alfred Hitchcock. True, Alfred Hitchcock works in a different medium, but he incorporates many of the same tools to create the myriad of moods and tones in his work. He is a Master of composition, in the use of lights and darks, and also in his ability to imbue a psychological tension into his pieces. For this side by side comparison we'll be looking at a still image from Psycho that I pulled off the web, along with an image from John Jude Palencar's website. I should pause here to thank Mr. Palencar for his express permission to use his work here, as well as to credit the Opera Company of Philadelphia who originally commissioned the Madame Butterfly piece that we'll be looking at. Links to these sites can be found at the bottom of this post, please check them out after your done reading.**

"Put light colors next to light colors and dark colors next to darks, then where you want the viewer to descend, put dark next to light." ~ Harvey Dunn.

This succinct sentence holds the cornerstone to quality illustrations, and the nature of communicating with images. Part of what Harvey Dunn is talking about here is a strong value structure. A strong value structure is absolutely essential towards crafting and communicating with an image. If that structure isn't there, the picture will be confusing and ineffective. As artists we are communicators, and through the conscious use of the tools at hand it becomes possible to communicate those ineffable qualities of life, rendering visible the invisible.

Pretty heady stuff, but there is a simple way to view this as well:

Mood=Tone=Value

To start with let's open ourselves to the wholeness of these terms, as they encapsulate multifaceted concepts.

Mood can be a slippery idea to get our hands on. People talk about mood all the time, but what are they really saying, what is a mood? As a working definition let's agree that mood refers to an emotional state of mind. We can talk about moods like, Joy, Elation, or their counter

As I was driving home the other grey, overcast day, I noticed a crow on the side of the road.

Living in the Pacific Northwest as I do, neither grey skies nor crows are an unusual sight,

Living in the Pacific Northwest as I do, neither grey skies nor crows are an unusual sight,

but as I looked up past the crow, there were some more over to the right....

...and even more to the left....

...and *more* fluttering eerily overhead...

I must say there was some looking-over-my-shoulder on the way home...

***

Magician Brain Brushwood tells a story on his blog about talking to Teller of Penn and Teller and how Teller ended up responding to a letter he wrote when frustrated by his industry. He’s talking magic, but isn’t that what we do, too? I think you will find it good advice for anyone writing a book.

Magician Brain Brushwood tells a story on his blog about talking to Teller of Penn and Teller and how Teller ended up responding to a letter he wrote when frustrated by his industry. He’s talking magic, but isn’t that what we do, too? I think you will find it good advice for anyone writing a book.

Wow, Kathy, I just read that whole letter (and what led up to it). I REALLY enjoyed that, and considering I wasn’t a huge fan of Penn and Teller (though they were good!), this is a good example of how much more there are to people than what we see…or “think” we see…sort of like magic (which I know some basic tricks, having done clown work).

And from that letter, a stunning simile: “But I really feel as if the things we create together are not things we devised, but things we discovered, as if, in some sense, they were always there in us, waiting to be revealed, like the figure of Mercury waiting in a rough lump of marble.”

Great stuff! Thanks for posting this

Donna