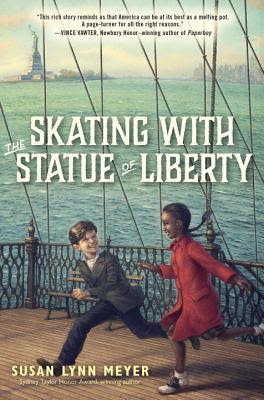

Skating with the Statue of Liberty continues the story of Gustave Becker begun in

Black Radishes. Gustave, now 12, and his family, along with his cousin Jean-Paul and his mother, all French Jews who have finally gotten American visas to leave Nazi-occupied Europe and sail to America. It's January 1942, and the ship the family is sailing must dock in Baltimore to avoid the Nazi U-boats patrolling the waters around New York City. Gustave is disappointed that the Statue of Liberty won't be his first view of America, but arriving in the US is his first taste of freedom since before WWII began.

However, life isn't all that easy for the Becker family in NYC. After staying with kind relatives, they find a small, affordable one room apartment with a shared bathroom on West 91st Street in Manhattan. His father must settle for a low-paying job a as janitor in a department store, and his mother ends up sewing decorations onto hats. Gustave begins school at Joan of Arc Junior High school, hoping the name is fortuitous for him in his new school, home and country.

School issn't too bad for Gustave, who already knows a little English, with except for his homeroom teacher, Mrs. McAdams, who believes that raising her voice at him will make Gustave understand her better. And she also decides that his name is too foreign and begins to call him Gus. He does have one African American student in his class, September Rose, but he doesn't understand why she keeps her distance. Eventually they do become friends, and face some nasty physical and verbal incidents because of it.

Gustave's English improves quickly, and he even gets an after-school job delivering laundry. He and his cousin Jean-Paul, who now lives with his mother at a relative's home in the Bronx, join a French boy scout troop run by a French priest and a French rabbi, the same rabbi who has begum preparing the two cousins for their Bar Mitzvahs. And through his friendship with September Rose, Gustave learns about the Double V campaign in which her older brother Alan and his friends are involved.

But Gustave also worries about his friend Marcel in hiding back in France. Luckily, he is able to write to his friend Nicole in Saint-Georges, France, whose father is in the French Resistance, so there is always hope that there will be good news about Marcel.

I had very mixed feelings about this novel. There is no real conflict in it, really. It is mostly about Gustave assimilation into American life. And while that is very interesting and realistic, it isn't very exciting. In fact, the whole issue around the Double V campaign, including the demonstration staged by Alan and his friends outside a department store in Harlem that refuses to hire African Americans is actually the most exciting part of the book and, I think, it should have been a story in its own right.

On the other hand, and perhaps because my dad was an immigrant, I personally liked reading about Gustave's life in America, perhaps because it is inspired on the author's father's real experiences after arriving in this country. For sure, America isn't portrayed perfect and even Gustave faces incidents of racism and anti-Semitism, but for the most part, he does make friends and has a nice support system in his family, Boy Scouts and school. I certainly appreciate his mixed feelings about which country to give his loyalty to and how that is resolved.

Themes of friendship, family, refugees, racism, hate, and acceptance make this historical fiction novel as relevant in today's world as in 1942. It is a quiet, almost gentle novel that will give young readers a real appreciation of what their family may have lived through coming to a new, unfamiliar country, finding a place in it and giving back as productive members of society.

This book is recommended for readers age 9+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Did the Statue of Liberty really skate in this book? Of course not, but you'll have to read to the end to find out where the title comes from.

Gustave lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just as Meyer's father did. His school, Joan of Arc Junior High School on West 93rd Street, is referred to in the book as a "skyscraper school" which only means that it was built up not out because of rising property values. But it is also a real school, now landmarked and on the NY Art Deco Registry. As you can see, it is an unusual school:

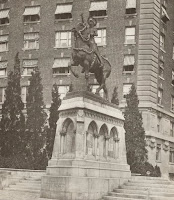

Gustave also spends a lot of time at the Joan of Arc statue in Riverside Park, at the end of West 93rd Street. It is also a famous landmark and you can read all about it at one of my favorite blogs,

Daytonian in Manhattan (he has better photos)

By Stephen Pevar

Chiefs at Verde Reservation, Arizona. Source: NYPL Labs Stereogranimator.

How would you feel if the government confiscated your land, sold it to someone else, and tried to force you to change your way of life, all the while telling you it’s for your own good? That’s what Congress did to Indian tribes 125 years ago today, with devastating results, when it passed the

Dawes Act.

During the 1800s, white settlers moved west by the tens of thousands, and the US cavalry went with them, battling Indian tribes along the way. One by one, tribes were forced to relinquish their homelands (on which they had lived for centuries) and relocate to reservations, often hundreds of miles away. By the late 1800s, some three hundred reservations had been created.

The purpose of the reservation system was, for the most part, to remove land from the Indians and to separate the Indians from the settlers. Reservations were usually created on lands not (yet) coveted by non-Indians. By the late 1800s, however, settlers were nearly everywhere, and Congress needed to develop a new strategy to prevent further bloodshed.

The government decided that instead of separating Indians from white society, Indians should be assimilated into white society. Assimilation of the Indians and the destruction of their reservations became the new federal goal.

Two very different social forces helped shaped this new policy: greed and humanitarianism. Many whites wanted Indian land and knew that they would have an easier time obtaining it if Indian tribes disappeared. This greed prompted Congress to pass the Dawes Act, also known as the General Allotment Act, in February 1887. The Dawes Act was also favored by many non-Indian social reformers who were aware that Indians were suffering unmercifully under the government’s existing reservation policies, and they sincerely believed that the best way to help Indians overcome their plight and their poverty was by encouraging assimilation. Although their motives differed, both groups pressured Congress to pass the Dawes Act. The objectives of the Act, as the US Supreme Court has noted, “were simple and clear cut: to extinguish tribal sovereignty, erase reservation boundaries, and force the assimilation of Indians into the society at large.” Indian tribes had no say in the matter and were not even consulted.

Most Indian tribes had no concept of private land ownership. Rather, land was communally owned and everyone worked together to gather what they could from the land and shared its bounty. In order to compel assimilation of the Indians, a scheme was developed that would undermine Indian life and culture at its core: individual Indians would be forced to own land for private use. Indians would be converted into capitalists.

To accomplish the new policy of assimilation, the Dawes Act authorized the President of the United States to divide communally-held tribal lands into separate parcels (“allotments”). Each tribal member was to be assigned an allotment and, after a twenty-five-year “trust” period, would be issued a deed to it, allowing the owner to sell it. Once the allotments were issued, the remaining tribal land (the “surplus” land) would be sold to non-Indian farmers and ranchers. Congress hoped that by allowing non-Indians to live on Indian reservations, the goals of the settlers and those of the humanitarian social reformers could both be satisfied: land would become available for non-In

Estoy leyendo...

Fe en disfraz [Faith in Disguise] by Mayra Santos Febres. A truffle of a novel, it tells the story Fe, a black historian and curator obsessed with the stories of sexual crimes committed against female slaves in Latin America, and a cyber-historian on her staff with whom she shares a charged romance fed by the documents of her research. Santos Febres plays with transvestism, subjugation, masochism and other tabu topics, woven artfully in her elegant prose. The story is fast-paced and cleverly told in only 115 pages; there’s nothing superfluous here. And it’s not all dessert either, within the text are multiple layers of propositions and inversions, as well as suggestive considerations on the role of memory, time and power. A brief and delightful read.

Latinos in the US

Assimilation or Transnationalism?

Silvia Pedraza

Professor of Sociology and American Culture

Un

Haven't read Faith in Disguise but plan on reading it. I love her writing.