new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: African Americans, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 24 of 24

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: African Americans in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 8/2/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Journals,

breast cancer,

US healthcare,

African Americans,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

oncology,

Flint Michigan,

JNCI,

Journal of the National Cancer Institute,

Mike Fillon,

black women,

ecomomic segregation,

health disparities,

racial mistrust,

South Side of Chicago,

Tuskagee Syphillis Study,

Add a tag

Black women in the United States have about a 41% higher chance of dying from breast cancer than white women. Some of that disparity can be linked to genetics, but the environment, lingering mistrust toward the health care system, and suspicion over prescribed breast cancer treatment also play roles, according to a new study from the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.

The post Solutions to reduce racial mistrust in medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

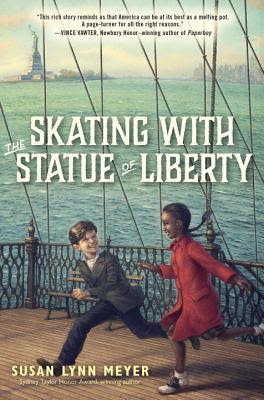

Skating with the Statue of Liberty continues the story of Gustave Becker begun in

Black Radishes. Gustave, now 12, and his family, along with his cousin Jean-Paul and his mother, all French Jews who have finally gotten American visas to leave Nazi-occupied Europe and sail to America. It's January 1942, and the ship the family is sailing must dock in Baltimore to avoid the Nazi U-boats patrolling the waters around New York City. Gustave is disappointed that the Statue of Liberty won't be his first view of America, but arriving in the US is his first taste of freedom since before WWII began.

However, life isn't all that easy for the Becker family in NYC. After staying with kind relatives, they find a small, affordable one room apartment with a shared bathroom on West 91st Street in Manhattan. His father must settle for a low-paying job a as janitor in a department store, and his mother ends up sewing decorations onto hats. Gustave begins school at Joan of Arc Junior High school, hoping the name is fortuitous for him in his new school, home and country.

School issn't too bad for Gustave, who already knows a little English, with except for his homeroom teacher, Mrs. McAdams, who believes that raising her voice at him will make Gustave understand her better. And she also decides that his name is too foreign and begins to call him Gus. He does have one African American student in his class, September Rose, but he doesn't understand why she keeps her distance. Eventually they do become friends, and face some nasty physical and verbal incidents because of it.

Gustave's English improves quickly, and he even gets an after-school job delivering laundry. He and his cousin Jean-Paul, who now lives with his mother at a relative's home in the Bronx, join a French boy scout troop run by a French priest and a French rabbi, the same rabbi who has begum preparing the two cousins for their Bar Mitzvahs. And through his friendship with September Rose, Gustave learns about the Double V campaign in which her older brother Alan and his friends are involved.

But Gustave also worries about his friend Marcel in hiding back in France. Luckily, he is able to write to his friend Nicole in Saint-Georges, France, whose father is in the French Resistance, so there is always hope that there will be good news about Marcel.

I had very mixed feelings about this novel. There is no real conflict in it, really. It is mostly about Gustave assimilation into American life. And while that is very interesting and realistic, it isn't very exciting. In fact, the whole issue around the Double V campaign, including the demonstration staged by Alan and his friends outside a department store in Harlem that refuses to hire African Americans is actually the most exciting part of the book and, I think, it should have been a story in its own right.

On the other hand, and perhaps because my dad was an immigrant, I personally liked reading about Gustave's life in America, perhaps because it is inspired on the author's father's real experiences after arriving in this country. For sure, America isn't portrayed perfect and even Gustave faces incidents of racism and anti-Semitism, but for the most part, he does make friends and has a nice support system in his family, Boy Scouts and school. I certainly appreciate his mixed feelings about which country to give his loyalty to and how that is resolved.

Themes of friendship, family, refugees, racism, hate, and acceptance make this historical fiction novel as relevant in today's world as in 1942. It is a quiet, almost gentle novel that will give young readers a real appreciation of what their family may have lived through coming to a new, unfamiliar country, finding a place in it and giving back as productive members of society.

This book is recommended for readers age 9+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Did the Statue of Liberty really skate in this book? Of course not, but you'll have to read to the end to find out where the title comes from.

Gustave lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just as Meyer's father did. His school, Joan of Arc Junior High School on West 93rd Street, is referred to in the book as a "skyscraper school" which only means that it was built up not out because of rising property values. But it is also a real school, now landmarked and on the NY Art Deco Registry. As you can see, it is an unusual school:

Gustave also spends a lot of time at the Joan of Arc statue in Riverside Park, at the end of West 93rd Street. It is also a famous landmark and you can read all about it at one of my favorite blogs,

Daytonian in Manhattan (he has better photos)

The Accidental Diva by Tia Williams 2004Putnam

Incredible Quote: "What he didn't tell Billie was how naive she sounded, telling him what hustling was about. In the fifth grade, he had more game in his size-five Adidas kicks than anyone at that party could ever hope to have. He hustled to survive. It was either get out there and sell the shit out of some crack, or eat grape jelly for dinner and hope the rat that bit you in your sleep wasn't carrying anything lethal. When Billie talked about hustling and playing the game, what she really meant was that she was ambitious. She was a go-getter. She set high goals for herself and met them, exceeded them. But the bottom line was that she had been born into a supportive, loving, comfortably middle-class family that took care of her and nurtured her and provided as security blanket. Jay came from nothing. Worse than nothing" (186).

One Sentence Review: A diverting read that is excellently paced and notable for both its now-outdated culture references and relevant social commentary on a number of topics ranging from class to fashion to race with a distinctive (in the best way possible) narrative voice.

I love this distinction Ms. Williams makes in her novel. I never realized that people describing themselves as "hustlers" bothered me until I read this passage and found myself nodding in agreement. Especially when celebrities use the term, I just find it ridiculous (excluding those who actually came up from nothing as opposed to those born to famous parents, etc etc) and Ms. Williams perfectly illustrates why. If you're thinking this quote is a bit heavy and shying away from this novel, never fear. This quote is expertly woven into a romp of a read that straddles the line between light and social commentary. It was exactly what I needed to end 2015, a lot of fun to read while making witty observations about being "the only" and exploring class issues that it managed to not only hold my attention but also cause me to pause and think after reading a passage.

The only negative I can see is that it confirmed my fears about the beauty industry in terms of its shallowness. But it's a unique (for me) professional setting for a book so it kept me turning the pages. This book was published in 2004, 12 years later it's sad that we're still having the same conversations. Through Billie the author tackles cultural appropriation (which Bille calls "ethnic borrowing" in the beauty and fashion industry and maybe it's just because of the rise of the Internet and public intellectuals and blogging but it had honestly never occurred to me that people were having these conversations pre-Twitter. That demonstrates my ignorance and I was happy to be enlightened while also being sad that white gaze still has so much power over beauty standards. Although it is getting better because it is harder for beauty companies, fashion companies and magazines to ignore being called out when they "discover" some trend people of color have been naturally gifted with/been doing/wearing for years.

Aside from the pleasing depth of the novel, it's a quick paced read. I actually felt caught up in Billie's sweeping romance and just as intoxicated as she did, I didn't want to resurface from her studio apartment. Honestly I'd like a prequel so that we can live vicariously through Billie, Renee and Vida's college years. And I'm so happy her friends served more of a role than just providing advice at Sunday brunch. Also Billie's family dynamics were absolutely hilarious and unexpected.

I dealt with similar issues to Billie and Jay although not on as large a scale, granted I'm not a professional (yet) but I can relate to the class issues that come up in a relationship with two different economic backgrounds. And not to be a cliche but especially when it's the woman who comes from the comfortable lifestyle and the preconceived notions that we have/that other have about us, difficulty is involved and so on a personal level I was able to really connect with Billie (and better understand Jay).

Negroland: a memoir by Margo Jefferson 2015

Pantheon/Knopf Doubleday

IQ "Average American women were killed like this [by men in crimes of passion] every day. But we weren't raised to be average women; we were raised to be better than most women of either race. White women, our mothers reminded us pointedly, could afford more of these casualties. There were more of them, weren't there? There were always more white people. There were so few of us, and it had cost so much to construct us. Why were we dying?" 168

There is so much to unpack here, so many quotes I want to discuss, which I will do later on in the review but if you only want to read one paragraph I'll try to make this one tidy.

One sentence review: There is something new to focus on with every reading and like all great works of literature there is something for everyone, the writing is flowery but I mean that in the best way possible.

I fell in love with the life of Margo Jefferson and the history of the Black American elite (think

Our Kind of People). I would say I'm on the periphery of the Negroland world so much of what Jefferson describes is vaguely familiar to me but obviously I am not a product of the '50s and '60s so that was all new to me. I appreciated Jefferson's honesty that she finds it difficult to be 100% vulnerable, I imagine that is part of why she chooses to focus so much on the historical. But at least she doesn't pretend that she will bare her soul, but she still manages to go pretty damn far for someone who believes it is easier to write about the sad/racist things. Jefferson eloquently explores the black body, class, Chicago, gender, mental illness and race from when she was a child into adulthood with a touch of dry humor here and there. Jefferson is the epitome of the cool aunt and I want to just sit at her feet everyday and learn (I was fortunate to hear her speak at U of C and it was magical, her voice is heavenly and she's FUNNY).

I understand complaints that the narrative is disjointed but Jefferson always manages to bring her tangents back to the main point. It is not simply random ramblings the author indulges in, each seemingly random thought serves a purpose that connects to the central theme of the chapter/passage. Jefferson does not owe us anything, yes she chose to write a memoir but she also chose to write a social history. She explores some of her flaws and manages to avoid what she so feared; "I think it's too easy to recount unhappy memories when you write about yourself. You bask in your own innocence. You revere your grief. You arrange your angers at their most becoming angles. I don't want this kind of indulgence to dominate my memories" (6). For someone raised to be twice as good and only show off to the benefit of the Black race, Jefferson thankfully manages to let us in on far more than I expected when it comes to the Black elite.

Jefferson comes at my life when she says, "At times I'm impatient with younger blacks who insist they were or would have been better off in black schools, at least from pre-K through middle school. They had, or would have had, a stronger racial and social identity, an identity cleansed of suspicion, subterfuge, confusion, euphemism, presumption, patronization, and disdain. I have no grounds for comparison. The only schools I ever went to were white schools with small numbers of Negroes" (119). I too attended majority white schools and have often wondered if I would have had an easier time identifying with other Black students in college (and even high school) if I had gone to majority Black schools instead of remaining on the periphery. She goes on to explain her impatience because she felt that for the first few years of school she was able to live her life unaware of race and I would agree, there were only a few incidents but mostly I felt free. So she's right, it's a trade off and ultimately we all end up in the same white world. I still think I should have gone to an HBCU just to see what it's like, to force myself to confront my own privilege but I managed to do that at my PWI and there's no point in worrying about it anymore. It's this matter-of-fact tone Jefferson uses throughout the book that I adored, she largely avoids sentimentality. Although she somehow manages to fondly look back at Jack & Jill which makes me sad that I don't share the same happy memories of the group and based on conversations with a few others on Twitter I am not alone in that (someone should research the history of Jack & Jill and explain why it has become so awful although I have my own theory).

Much has already been said about how candidly Jefferson discusses depression, an aspect of mental health that was not discussed in the Black community. Thus I do not wish to dwell on the topic since writers far more articulate than I have mentioned it in their reviews, but I appreciate her talking about it and I know what she means. Slowly but surely the 'strong Black woman' facade is being allowed to crack and we are all the better for it. I wish she had delved a bit into Black women and eating disorders because she mentions how much she loved Ballet and the ideal beauty standards of the Black elite (no big butts or noses for example) but maybe this is not something she witnesses personally. Jefferson mentions that when Thurgood Marshall and Audrey Hepburn died around the same time, she and her friend felt guilty for caring more about Hepburn's death because of all she symbolized for them. At first I raised my eyebrows at this sign of racial disloyalty but she notes what Hepburn meant to her; "And the longing to suffer nothing at all, to be rewarded, decorated, festooned for one's charms and looks, one's piquant daring, one's winning idiosyncrasies: Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face and Breakfast at Tiffany's. Equality in America for a bourgeois black girl meant equal opportunity to be playful and winsome. Indulged" (200). And I understood exactly what she meant. It's why I cling to Beyonce,

Carmen Jones (and Dorothy Dandridge by extension), Janelle Monae etc etc. I can't think of a Black manic pixie dream girl but I'd love to have a Black girl play one, to be able to complain about a character we have long been denied.

On Black men & women; "But the boys ruled. We were just aspiring adornments, and how could it be otherwise? The Negro man was at the center of the culture's race obsessions. The Negro woman was on the shabby fringes. She had moments if she was in show business, of course; we craved the erotic command of Tina Turner, the arch insolence of Diana Ross, the melismatic authenticity of Aretha. But in life, when a Good Negro Girl attached herself to a ghetto boy hoping to go street and compensate for her bourgeois privilege, if she didn't get killed with or by him, she usually lived to become a socially disdained, financially disabled black woman destined to produce at least one baby she would have to care for alone. What was the matter with us? Were we plagued by some monstrous need, some vestigial longing to plunge back into the abyss Negros had been consigned to for centuries? Was this some variant of survivor guilt? No, that phrase is too generic. I'd call it the guilty confusion of those who were raised to defiantly accept their entitlement. To be more than survivors, to be victors who knew that victory was as much a threat as failure, and could be turned against them at any moment" (169). Jefferson embraces feminism and pushes back on the constraints of Black womanhood.

I've already picked this book up and re-read random passages which is rare for me so soon after finishing it the first time (this is what happens when you have a towering TBR pile). I took an African American Autobiography class in college and I really hope this book gets added to the syllabus. It combines so many topics of interest to me, acknowledges so many greats in Black history, exposes some secrets of the Black upper class (passing, brown paper bag test) while combining history and memoir, absolutely captivating. I instinctively knew I would need to buy this book (ended up getting it autographed) and I am so glad I did. The cover is phenomenal.

By: JOANNA MARPLE,

on 2/19/2016

Blog:

Miss Marple's Musings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Historical fiction,

Boston,

19th century,

Segregation,

E B White,

African Americans,

Perfect Picture Book Friday,

PPBF,

discrimination in education,

How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial,

Roberts v Boston,

Sarah C Roberts,

Susa E Goodman,

the First Step,

Add a tag

Another book for Black History Month.

Title: the First Step, How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial

Written by: Susan E. Goodman

illustrated by: E. B. Lewis

Published by: Bloomsbury, 2015

Genre: historical fiction, 40 pages

Themes: segregation, discrimination in education, Boston, Sarah C Roberts, African Americans

Ages: 7-11

Opening:

Sarah Roberts was four … Continue reading →

By: JOANNA MARPLE,

on 2/5/2016

Blog:

Miss Marple's Musings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Perfect Picture Book Friday,

WNDB,

Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton,

Diversity Day 2016,

activities for classroom,

picture book,

poetry,

literacy,

diversity,

biography,

picture books,

black history month,

slavery,

Don Tate,

African Americans,

Add a tag

Celebrating Black History Month!

Title: Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses HortonPoet:

Author and illustrator: Don Tate

Publisher: Peachtree Books, 2015

Themes: slavery, illiteracy, poetry, African American, perseverance,

Genre: biography

Ages: 6-9

Opening:

GEORGE LOVED WORDS. He wanted to learn how to read, but George was enslaved. He and his family lived … Continue reading →

Hank and Theo McCallum are about as close as brothers can be, so when it looks like war is inevitable, their plan is to enlist in the navy together. That way, they can look out for each other. Except their father isn't having any of that - his thinking is that it would only take one torpedo to kill both his sons. Before they even leave the house to enlist, it Hank for the navy, Theo for….the Army Air Corps.

A few weeks later, Hank and Theo are off to the Navy and Army, and it isn't long after boot camp that Hank finds himself on the aircraft carrier USS

Yorktown, heading to the Pacific Ocean after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. On board the

Yorktown, Hank is an airedale, which means his duties are plane-handling on the flight deck, doing everything except flying the aircraft he takes care of. But Hank also has a reputation for always wanting to throw a little ball. Before the Navy, Hank and Theo were all about baseball, and when they left for the war, Theo gave his well-used glove to Hank. Now, with two gloves and a ball, Hank was always looking for someone to throw with during down time.

Once in the Pacific, the

Yorktown doesn't see any real action until after a visit to Pearl Harbor. Seeing the aftermath of the attack there, however, finally makes the war real for Hank, but he has absolute faith that the US will win. Meantime, he meets a throwing partner, who actually has a few baseball tricks he can teach Hank, who is pretty good himself. Mess Attendant First Class Bradford had played in the Negro Leagues before the war, but now he is generally stuck below deck, serving the pilots, sleeping far down in the ship, even below the torpedoes, because of the Navy's policy of racial segregation.

Hank and Bradford soon become friends and throwing buddies, often joined by two of the pilots whose planes Hank services whenever they fly missions. At first, the

Yorktown and its partner ship the

Lexington still don't see much action, but a bad attack on the ships causes the

Lexington to sink and the

Yorktown to have to limp back to Pearl Harbor for repairs.

With time on their hands, Hank, Bradford and their two pilot friends decide to head to Waikiki Beach, even though Bradford isn't allowed to be there because he is African American. When two policemen try to get them to leave, they refuse and they prevail.

Soon the

Yorktown is really to sail again, headed for Midway Island and a life and death battle with the Japanese. Once again, the Yorktown is hit, and sinks. Can Hank survive a sinking ship?

Dead in the Water is narrated by Hank and although he and Theo are close, we don't really ever know how Theo is doing. This is Hank's story (Theo is book 3). Lynch always manages to make his narrators so believable and so historically real sounding, and Hank is no different. He has a real 1940s way of speaking. My only complaint is that there is too much baseball involved. On the other hand, Lynch doesn't overdo it on the military stuff, including combat details. There's just enough description and not too, too detailed on that front.

At first, I was afraid that taking on the racism that black sailors faced in the Navy (in fact, in all the Armed Forces in WWII), might be a bit over the top in a book like this, but it really works and he manages to make his points quite nicely, the beach incident is packed with tension. I did find it a little surprising that Hank, baseball obsessed as he is, never heard of the Negro Leagues, and the Newark Eagles, for which Bradford played.

Dead in the Water is the third Chris Lynch book I've read, and I have to be honest and say they have all been very good. The story flows nicely, they are historically correct, and most important to me, Lynch doesn't glorify war.

And, of course, now I am curious to know what happened to Hank and his friends.

This book is recommended for readers age 11+

This book was an EARC received from

NetGalley

.jpg) Barton, Chris. 2015. The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Illustrated by Don Tate.

Barton, Chris. 2015. The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Illustrated by Don Tate.

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch is a nonfiction picture book for school-age readers and listeners. More than just an inspirational story of a former slave who becomes a landholder, judge, and United States Congressman, it is a story that focuses on the great possibilities presented during the period of Reconstruction.

"In 1868 the U.S. government appointed a young Yankee general as a governor of Mississippi. The whites who had been in charge were swept out of office. By river and by railroad, John Roy traveled to Jackson to hand Governor Ames a list of names to fill those positions in Natchez. After John Roy spoke grandly of each man's merits, the governor added another name to the list: John Roy Lynch, Justice of the Peace.

Justice. Peace. Black people saw reason to believe that these were now available to them. Just twenty-one, John Roy doubted that he could meet all those expectations. But he dove in and learned the law as fast as he could."

Sadly, the reason that John Roy Lynch's story is amazing to today's reader is because the opportunities that abounded during Reconstruction dried up and disappeared as quickly as they had come. The period of hope and optimism for African Americans in the years from 1865 to 1877, gets scant attention today. The life of John Roy Lynch is an excellent lens through which to view Reconstruction.

To make sometimes difficult scenes accessible to younger readers, Don Tate employs a self-described, "naive ... even whimsical" style. It works well with the sepia-tinged hues that help to set the time frame.

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch is a powerful, historical reminder of what was, what might have been, and what is.

A Timeline, Historical Note, Author's Note, Illustrator's Note, For Further Reading, and maps round out the book.

Advance Reader Copy provided by

February is Black History Month and this year's theme is A Century of Black Life, History, and Culture. It is a good time to look back and reflect on the changes and contributions of African Americans to the fabric of American life in the last century.

For example, more and more we are learning about the achievements of African American soldiers in World War II. Books like

The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny and the Fight for Civil Rights by Steve Sheinkin,

Courage Has No Color: The True Story of the Triple Nickles by Tanya Lee Stone,

Double Victory: How African American Women Broke the Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win World War II by Cheryl Mullenbach, and

The Double V Campaign: African Americans and World War II by Michael L. Cooper all highlight the contributions these courageous Americans made in the fight for democracy even as they were being denied their basic civil rights.

Now, J. Patrick Lewis and Gary Kelly, the same duo who produced the lovely book

And the Soldiers Sang, about the Christmas Truce in 1914 during World War I, have written a book introducing us to the brave and talented unsung heroes of the 15thNew York National Guard, which was later federalized as the 369th Infantry Regiment, soldier that the Germans dubbed the Harlem Hellfighters. "because of their tenacity."

In beautifully lyrical prose, Lewis tells how bandleader James "Big Jim" Reese Europe was recruited to organize a new black regiment in New York. Traveling around in an open air double-decker bus, his band played on the upper level, while the new recruits lined up below. Willing to fight like any American, enthusiastic patriotism may have motivated these young men, but racism at home, and in the army resulted in segregation while training and doing the kind of grunt work not given to white soldiers in Europe, even as they entertained tired soldiers with [Jim] Europe's big band jazz sounds.

Each page tells small stories of the 369th: their heroics, homesickness, the bitter cold, the lynchings back home, the fighting on the French front lines. Extending the narrative are Gary Kelly's dark pastel illustrations. Kelly's visual representations of the men of the 369th Infantry are both haunting and beautiful. He has used a palette of earth tones and grays, so appropriate for the battlefields and uniforms of war, but with color in the images of patriotism, such as flags and recruiting posters, and highlighting the reasons we go to war. Some of Kelly's image may take your breath away with their stark depiction of, for example, the hanging figures, victims of a lynching, or the irony of the shadowy faces of people in a slave ship hull, shackles around their necks, on their voyage to America and slavery next to a soldier heading to Europe to fight for freedom and democracy.

Harlem Hellfighters is an exquisitely rendered labor of love, but readers may find it a little disjointed in places. Lewis's fact are right, though, and he also includes a Bibliography for readers who might want to know more or those who just want more straightforward nonfiction books about the 369th Regiment.

As a picture book for older readers,

Harlem Hellfighters would pair very nicely with Walter Dean Myer's impeccable researched and detailed book

The Harlem Hellfighters: When Pride Met Courage written with Bill Miles. Myer's gives a broader, more historical view of these valiant men. These would extend and compliment each other adding to our understanding and appreciation of what life was like for African American soldiers in World War I.

Both books is recommended for readers age 10+

Harlem Hellfighters was bought for my personal library

February is Black History Month

By: Shelf-employed,

on 12/22/2014

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book review,

Civil Rights,

Advance Reader Copy,

African Americans,

YA,

WWII,

nonfiction,

racism,

J,

Navy,

Non-Fiction Monday,

sailors,

Add a tag

Sheinkin, Steve. 2014. The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights. New York: Roaring Brook.

The Port Chicago 50, as they became known, were a group of African American Navy sailors assigned to load munitions at Port Chicago in California, during WWII. The sailors' work detail options were limited; the Navy was segregated and Blacks were not permitted to fight at sea. The sailors worked around the clock, racing to load ammunition on ships headed to battle in the Pacific. Sailors had little training and were pressured to load the dangerous cargo as quickly as possible.

After an explosion at the port killed 320 men, injured many others, and obliterated the docks and ships anchored there, many men initially refused to continue working under the same dangerous conditions. In the end, fifty men disobeyed the direct order to return to work. They were tried for mutiny in a case with far-reaching implications. There was more at stake than the Naval careers of fifty sailors. At issue were the Navy's (and the country's) policy of segregation, and the racist treatment of the Black sailors. Years before the Civil Rights movement began, the case of the Port Chicago 50 drew the attention of the NAACP, a young Thurgood Marshall, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Through the words of the young sailors, the reader of The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights relives a slice of history as a Black sailor in 1944.

Steven Sheinkin combines excellently researched source materials, a little-known, compelling story, and an accessible writing style to craft another nonfiction gem.

Read an excerpt of The Port Chicago 50 here.

Contains:

- Table of Contents

- Source Notes

- List of Works Cited

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Credits

- Index

Advance Reader Copy supplied by publisher.

By: Shelf-employed,

on 10/27/2014

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

memoir,

nonfiction,

writing,

religion,

New York,

family life,

Civil Rights,

J,

novels in verse,

1960s,

Non-Fiction Monday,

South Carolina,

bio,

African Americans,

Add a tag

Woodson, Jacqueline. 2014. Brown Girl Dreaming. New York: Penguin.

Woodson, Jacqueline. 2014. Brown Girl Dreaming. New York: Penguin.

Despite the title, Brown Girl Dreaming is most certainly not just a book for brown girls or girls. Jacqueline Woodson's memoir-in-verse relates her journey to discover her passion for writing. Her story is framed by her large, loving family within the confines of the turbulent Civil Rights Era.

Sometimes a book is so well-received, so popular, that it seems that enough has been said (and said well); anything else would just be noise. Rather than add another Brown Girl Dreaming review to the hundreds of glowing ones already in print and cyberspace, I offer you links to other sites, interviews and reviews related to Brown Girl Dreaming. And, I'll pose a question on memoirs in children's literature.

First, the links:

And now something to ponder:

As a librarian who often helps students in choosing books for school assignments, I have written many times about the

dreaded biography assignment - excessive page requirements, narrow specifications, etc.

Obviously, a best choice for a children's book is one written by a noted children's author. Sadly, many (by no means

all!) biographies are formula-driven, series-type books that are not nearly as engaging as ones written by the best authors. Rare is the author of young people's literature who writes an

autobiography for children as Ms. Woodson has done. When such books exist, they are usually memoirs focusing only on the author's childhood years. This is perfectly appropriate because the reader can relate to that specified period of a person's lifetime. Jon Sciezska wrote one of my favorite memoirs for children,

Knucklehead, and Gary Paulsen's,

How Angel Peterson Got his Name also comes to mind as a stellar example. These books, however, don't often fit the formula required to answer common student assignment questions, i.e., birth, schooling, employment, marriages, accomplishments, children, death. Students are reluctant to choose a book that will leave them with a blank space(s) on an assignment.

I wonder what teachers, other librarians and parents think about this. Must the biography assignment be a traditional biography, or can a memoir (be it in verse, prose, or graphic format) be just as acceptable? I hate to see students turn away from a great book because it doesn't fit the mold. If we want students to be critical thinkers, it's time to think outside the box and make room for a more varied, more diverse selection of books.

By: MissA,

on 8/14/2014

Blog:

Reading In Color

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book review,

fantasy,

Middle Grade,

urban fantasy,

Zetta Elliott,

Throwback Thursday,

African Americans,

3.5/5,

multicultural,

Add a tag

Ship of Souls

Ship of Souls by Zetta Elliott (2011, ARC)

Amazon Publishing

Rating: 3.5/5

IQ "Kids on my block called 'reject'. Grown folks at church called me an 'old soul'. One girl at school told me I talked like a whiteboy. But when I ask Mom about it she just said, 'you are black. And nothing you say, or do, or pretend to be will ever change that fact. So just be yourself, Dmitri. Be who you are." pg. 3

Dmitri, known as D, is living with a foster family after his mother dies of breast cancer. D is used to having his foster mom all to himself, when she takes in Mercy, a crack-addicted baby he finds himself unable to cope. He is at a new school and while tutoring he becomes friend with Hakeem, a basketball star who needs extra math help and Nyla, a military brat both boys have crushes on. Sometimes after school D bird watches in Prospect Park and he discovers a mysterious bird, Nuru that can communicate with him. He enlists Hakeem and Nyla to help him help Nuru (who is injured) escape evil forces, the ghosts of soldiers that died during the Revolutionary War. They journey from Brooklyn to the African Burial Ground in Manhattan to assist Nuru in freeing the souls that reside there.

I wish some of the fantasy elements had been developed a bit further, such as Nuru's role, his dialogue also came across sounding a little ridiculous and heavy on the 'wise mentor' scale. The characters did come across as having a message. It is made very clear that Hakeem is Muslim and Nyla is 'different from the stereotype. I wish the individuality of the characters had come off in a more subtle way (for example when Hakeem describes how his older sister listed all Muslim basketball players to convince his dad to let him play. And then Hakim lists them all and weaves in tidbits about the hijab. It came across as stilted for middle school dialogue). But then again this book is intended for a younger audience who need it hammered in that it's dangerous to define people and put them in boxes. I also wish the book had been longer just by a few chapters, selfishly because I wanted more historical tidbits but also because I felt that the fantasy elements happened so fast as did the sudden strong friendship with Hakeem and Nyla. And the love triangle made me sad but that's not the author's fault! Although I would have been happy without it.

Yet again Zetta Elliott seamlessly blends together history and fantasy, Black American history that is often ignored in textbooks. Unlike the descriptions of the characters I found the historical tidbits woven in artfully. There are so many goodies in here about the importance of working with other people, that heroes need not go it alone. This is especially vital because the author makes it explicitly clear that D is unbearably lonely but he keeps himself isolated from other people because he doesn't want to be abandoned or disappointed or lose them in a tragic way as happened with his mother. The author does a great job of making you truly feel and understand D's loneliness and your heart aches for him. Also while I didn't think the friendship had enough time to really grow into the strong bonds that developed so quickly, it was a very genuine friendship (once you suspend your disbelief) in terms of doing anything and everything for your friends and believing the seemingly improbable. It is also clear that the author has a strong appreciation of nature and that makes the fantasy elements more interesting while also making it appear more realistic.

Ship of Souls is a great story that focuses on a portion and population of the American Revolution that is completely ignored by most history outlets. The fantasy world is well-thought out, I only wish the book had been longer to explain more about the world D and his friends get involved in as well as more time to believably develop their friendship. The characters are strong, but they were written with a heavy hand that tries hard to point out how they defy stereotypes. I devoured the story not just because of the length but because it is so different from anything else out there and it's a lovely addition to the YA/MG fantasy world. I can't wait to see what the author does next and again I adored her first YA novel

A Wish After Midnight. I recommend both books.

Disclosure: Received from the author, who I do consider a wonderful friend and mentor. Many thanks Zetta!

By: Alice,

on 4/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Law,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

slavery,

America,

African Americans,

*Featured,

criminal justice,

criminal convictions,

Felon disfranchisement,

History of American Citizenship,

Living in Infamy,

Pippa Holloway,

voting rights,

felon,

disfranchisement,

disfranchise,

Add a tag

By Pippa Holloway

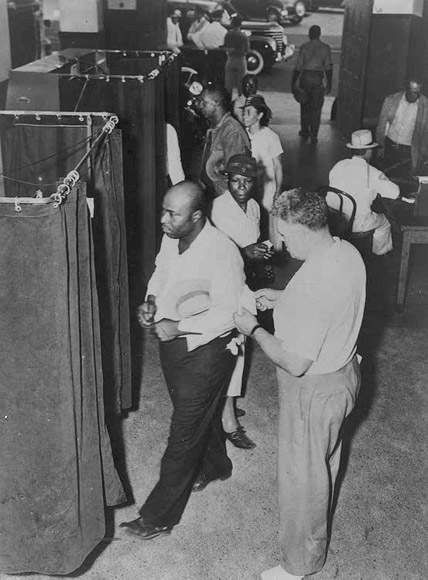

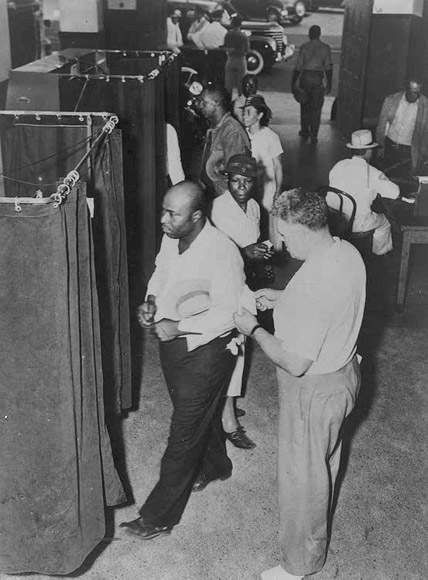

Nearly six million Americans are prohibited from voting in the United States today due to felony convictions. Six states stand out: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. These six states disfranchise seven percent of the total adult population – compared to two and a half percent nationwide. African Americans are particularly affected in these states. In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than one in five African Americans is disfranchised. The other three are not far behind. Not only do individuals lose voting rights when they are incarcerated, on probation, or paroled, a common practice in many states, but some or all ex-felons are barred from voting. All six of these states have non-automatic restoration processes that make it difficult or impossible to have one’s rights restored. Not coincidentally, all of these states maintained a system of racial slavery until the Civil War.

Voters at the Voting Booths. ca. 1945. NAACP Collection, The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the other end of the spectrum are northeastern states, mostly those in New England, which put up few obstacles to voting by convicted individuals. Maine and Vermont are the only states in the nation that do not disfranchise anyone for a crime, even individuals who are incarcerated. Among the remaining 48 states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire disfranchise the smallest percentage of convicted individuals. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania are also far below the national average.

Generalizations about regional difference are complex should be made cautiously. Although the six states with the highest rates of disfranchisement are all in the South, six other states also impose life-long disfranchisement for some or all felons. Arizona and Nevada have relatively high rates of felon disfranchisement. Midwestern states, particularly Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan, have low rates of felon disfranchisement, as does North Dakota. Nonetheless, the Northeast and South stand in stark contrast.

Regional differences in felon disfranchisement today are the result of regionally divergent histories of slavery and criminal justice. New England states had outlawed slavery by 1800. Soon, they also stopped treating convicts like slaves, barring state-administered corporal punishment for criminal offenses in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Instead, northeastern states embraced an ideology of criminality that emphasized rehabilitation. This attitude toward both slavery and punishment led many citizens and lawmakers in the northeast to oppose disfranchisement of convicts or at least curb the reach of this punishment. In the colonial era, Connecticut limited the courts that could deny convicts the vote. Maine’s 1819 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to disfranchise for crime. Vermont ended the practice in 1832. In other northeastern states proponents of such disfranchisement measures faced strong opposition. For example, Pennsylvania’s 1873 constitutional convention restricted felon disfranchisement to those convicted of election-related crimes; an effort to disfranchise convicts in Maryland in 1864 passed only after a long debate.

In contrast in the nineteenth-century South two groups were permanently cast out of full citizenship: African Americans and convicts. Although the enslavement of African Americans ended in 1865, “infamy” – the legal status of those convicted of serious crimes – was imposed on a growing number of the new black citizens. Accusations of prior crimes were used in the 1866 election as one of the first tools used to deny the vote to former slaves. In the 1870s, nearly every state in the former Confederacy (Texas being the exception) modified its laws to disfranchise for petty theft, a move celebrated by white leaders as a step toward disfranchising African Americans.

The legacy of slavery and segregation in the South is important to this story but so is the different regional trajectory of criminal justice. All southern states except South Carolina and Georgia (states today that still have among the lowest rates of disfranchisement in the South) enacted laws disfranchising for crime between 1812 and 1838, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this punishment anywhere in the region. Furthermore, southern states rejected the concept of criminal rehabilitation and focused instead on punishment. After the Civil War “convict lease” systems replicated in many ways the system of slavery for those who fell into it, creating a class of mostly-black individuals who were subject to physical punishment, public abuse, and humiliation, and denied voting rights.

In the past, as is also true today, individuals with criminal convictions fought long battles to regain their voting rights. Far from being a population that is uninterested in politics, individuals barred from voting have challenged obstacles to re-enfranchisement and overcome tremendous hurdles to have their voting rights restored. Consider the case of Jefferson Ratliff, an African American farmer living in Anson County, North Carolina, who in 1887 paid the court an astounding $14 to have his citizenship rights restored, ten years after his conviction for larceny (including three years’ incarceration) for stealing a hog. In Giles County, Tennessee in 1888 a man named Henry Murray paid $2.70 in court costs in an unsuccessful effort to have his voting rights restored. In other cases, poor and illiterate individual petitioners facing a complicated legal process sought help from friends and neighbors. In Georgia, Lewis Price petitioned Governor William Y. Atkinson in 1895 for a pardon so that he could vote. He explained, “I am a poor ignorant negro and I have no money to pay to the lawyers to work for me. So I have to depend on my friends to do all of my writing.”

The historical record shows that state and local governments have consistently failed, throughout the nation’s history, to enforce these laws in a fair and uniform way. Coordinating voter registration lists with criminal court records and pardon records — difficult in today’s world of information technology — was nearly impossible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. People who should have been able to vote were often denied the vote due to false allegations of disfranchising offenses; convictions were secured through suspect judicial processes prior to an election for partisan ends; and people who should have been disfranchised often voted. Sometimes these appear to have been honest mistakes made by officials charged with merging complicated statutory and constitutional requirements with voter registration data and court records. In many cases though, other agendas—partisan, racial, personal—seem to have been at work. In short, felon disfranchisement laws have long been subject to error and abuse.

Race both rationalized and motivated laws imposing lifelong disfranchisement for certain criminal acts in the post-Civil War period. Since then a variety of factors have led to the persistent sense, particularly in southern states, that individuals with prior criminal convictions are marked with a disgrace and contamination that is incompatible with full citizenship. Felon disfranchisement today preserves slavery’s racial legacy by producing a class of individuals who are excluded from suffrage, disproportionately impoverished, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and often subject to labor for below-market wages. In these six southern states, the ballot box is just as out of reach for former convicts as it was for enslaved African Americans two centuries ago.

Dr. Pippa Holloway is the author of Living in Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, published Oxford University Press in December 2012. She is Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. Contemporary data comes from Christopher Uggen, Sara Shannon, Jeff Manza, “State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

explorer,

infographic,

African Americans,

novices,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

social explorer,

demography,

Online products,

employment rates,

household ownership,

per capita income,

demographic,

interface,

History,

interactive,

black history month,

Current Affairs,

Geography,

America,

census,

Add a tag

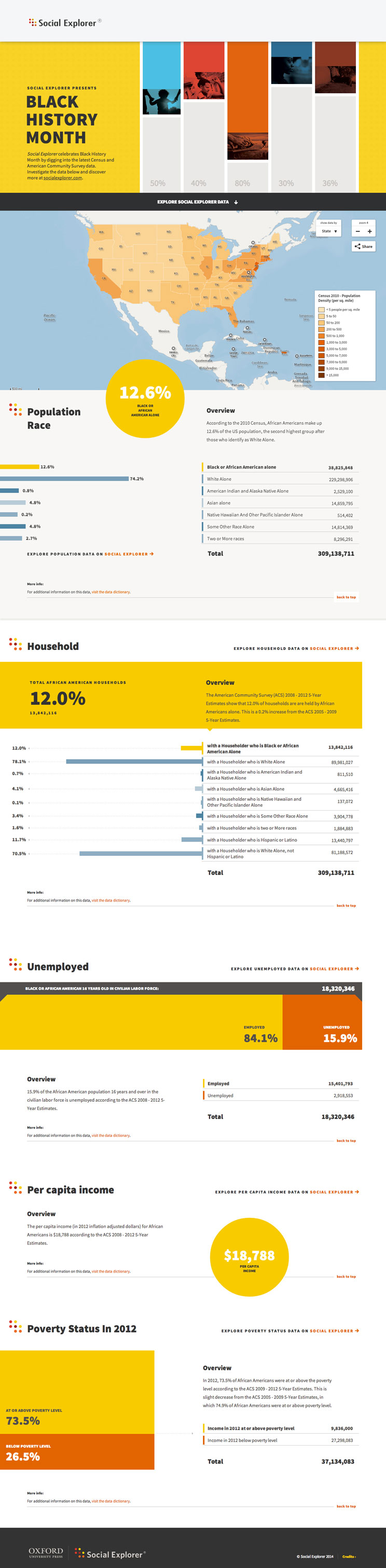

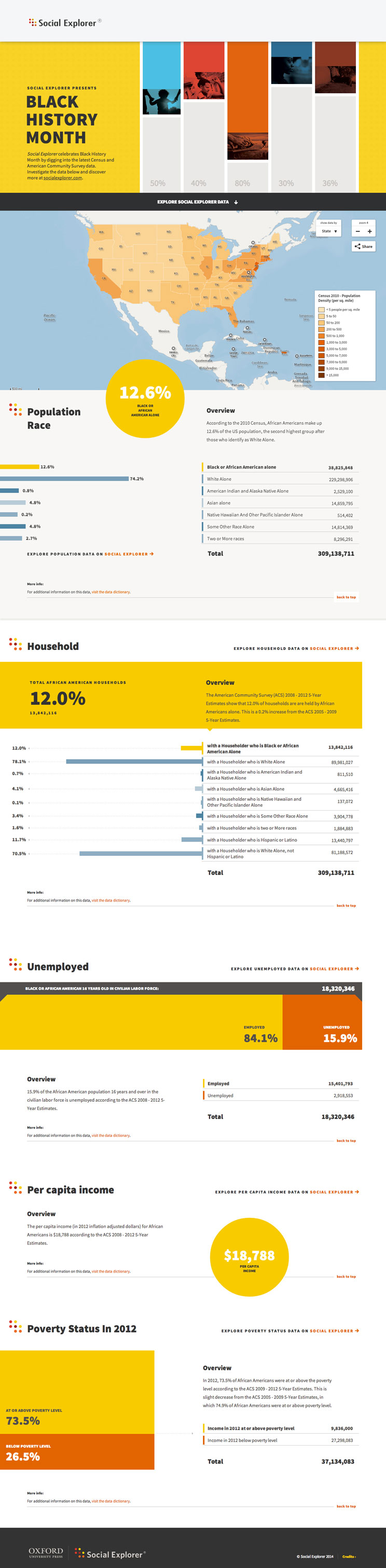

In celebration of Black History Month, Social Explorer has put together an interactive infographic with statistics from the most recent Census and American Community Survey. Dig into the data to find out about current African American household ownership, employment rates, per capita income, and more demographic information.

Take a sneak peak below and visit Social Explorer Presents Black History Month for the full, interactive infographic.

Social Explorer provides quick and easy access to current and historical census data and demographic information. The easy-to-use web interface lets users create maps and reports to illustrate, analyze, and understand demography and social change. In addition to its comprehensive data resources, Social Explorer offers features and tools to meet the needs of demography experts and novices alike. From research libraries to classrooms to government agencies to corporations to the front page of the New York Times, Social Explorer helps the public engage with society and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post African American demography [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/24/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

black history month,

woodson,

African American Studies,

african,

strived,

United States,

Abraham Lincoln,

leffler,

fredrick douglass,

American National Biography,

fredrick,

African Americans,

*Featured,

luncheon,

Online Products,

ANB,

African American lives,

Dr Carter Woodson,

abernathy,

attachment_35720,

History,

US,

Add a tag

February marks a month of remembrance for Black History in the United States. It is a time to reflect on the events that have enabled freedom and equality for African Americans, and a time to celebrate the achievements and contributions they have made to the nation.

Dr Carter Woodson, an advocate for black history studies, initially created “Negro History Week” between the birthdays of two great men who strived to influence the lives of African Americans: Fredrick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. This celebration was then expanded to the month of February and became Black History Month. Find out more about important African American lives with our quiz.

Rev. Ralph David Abernathy speaks at Nat’l. Press Club luncheon. Photo by Warren K. Leffler. 1968. Library of Congress.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men & women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. The American National Biography is the first biographical resource of this scope to be published in more than sixty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post African American lives appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

African Americans,

social history,

*Featured,

Robert Williams,

Online Products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Black English,

cultural history,

Ebonics,

Oxford AASC,

Tim Allen,

“ebonics”,

“ebonics”—a,

aave,

languages—rubbed,

History,

US,

African American Studies,

educators,

journalists,

linguists,

Add a tag

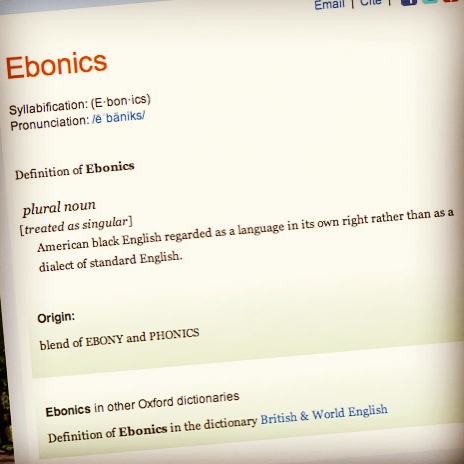

By Tim Allen

On this day forty years ago, the African American psychologist Robert Williams coined the term “Ebonics” during an education conference held at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. At the time, his audience was receptive to, even enthusiastic about, the word. But invoke the word “Ebonics” today and you’ll have no trouble raising the hackles of educators, journalists, linguists, and anyone else who might have an opinion about how people speak. (That basically accounts for all of us, right?) The meaning of the controversial term, however, has never been entirely stable.

For Williams, Ebonics encompassed not only the language of African Americans, but also their social and cultural histories. Williams fashioned the word “Ebonics”—a portmanteau of the words “ebony” (black) and “phonics” (sounds)—in order to address a perceived lack of understanding of the shared linguistic heritage of those who are descended from African slaves, whether in North America, the Caribbean, or Africa. Williams and several other scholars in attendance at the 1973 conference felt that the then-prevalent term “Black English” was insufficient to describe the totality of this legacy.

Ebonics managed to stay under the radar for the next couple of decades, but then re-emerged at the center of a national controversy surrounding linguistic, cultural, and racial diversity in late 1996. At that time, the Oakland, California school board, in an attempt to address some of the challenges of effectively teaching standard American English to African American schoolchildren, passed a resolution recognizing the utility of Ebonics in the classroom. The resolution suggested that teachers should acknowledge the legitimacy of the language that their students actually spoke and use it as a sort of tool in Standard English instruction. Many critics understood this idea as a lowering of standards and an endorsement of “slang”, but the proposed use of Ebonics in the classroom did not strike most linguists or educators as particularly troublesome. However, the resolution also initially characterized Ebonics as a language nearly entirely separate from English. (For example, the primary advocate of this theory, Ernie Smith, has called Ebonics “an antonym for Black English.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 21)) The divisive idea that “Ebonics” could be considered its own language—not an English dialect but more closely related to West African languages—rubbed many people the wrong way and gave a number of detractors additional fodder for their derision.

Linguists were quick to respond to the controversy and offer their own understanding of “Ebonics”. In the midst of the Oakland debate, the Linguistic Society of America resolved that Ebonics is a speech variety that is “systematic and rule-governed like all natural speech varieties. […] Characterizations of Ebonics as “slang,” “mutant,” ” lazy,” “defective,” “ungrammatical,” or “broken English” are incorrect and demeaning.” The linguists refused to make a pronouncement on the status of Ebonics as either a language or dialect, stating that the distinction was largely a political or social one. However, most linguists agree on the notion that the linguistic features described by “Ebonics” compose a dialect of English that they would more likely call “African American Vernacular English” (AAVE) or perhaps “Black English Vernacular”. This dialect is one among many American English dialects, including Chicano English, Southern English, and New England English.

And if the meaning of “Ebonics” weren’t muddy enough, a fourth perspective on the term emerged around the time of the Oakland debate. Developed by Professor Carol Aisha Blackshire-Belay, this idea takes the original view of Ebonics as a descriptive term for languages spoken by the descendants of West African slaves and expands it to cover the language of anyone from Africa or in the African diaspora. Her Afrocentric vision of Ebonics, in linguist John Baugh’s estimation, “elevates racial unity, but it does so at the expense of linguistic accuracy.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 23)

The term “Ebonics” seems to have fallen out of favor recently, perhaps due to the unpleasant associations with racially-tinged debate that it engenders (not to mention the confusing multitude of definitions it has produced!). However, the legacy of the Ebonics controversy that erupted in the United States in 1996 and 1997 has been analyzed extensively by scholars of language, politics, and race in subsequent years. And while “Ebonics”, the word, may have a reduced presence in our collective vocabulary, many of the larger issues surrounding its controversial history are still with us: How do we improve the academic achievement of African American children? How can we best teach English in school? How do we understand African American linguistic heritage in the context of American culture? Answers to these questions may not be immediately forthcoming, but we can, perhaps, thank “Ebonics” for moving the national conversation forward.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Ebonics’ in flux appeared first on OUPblog.

Well, baseball season is winding down, and my beloved Phillies have been all but statistically eliminated from any hope of the playoffs, but it was baseball season, and that's always good enough for me. I'll wrap up the season with a baseball-themed book. Below is my review of the book and CD, Satchel Paige, as it appeared in the September 2012, edition of School Library Journal.

Satchel Paige. By Lesa Cline-Ransome. CD. 21:14 min. Live Oak Media. 2012. CD with hardcover book, ISBN 978-1-4301-1088-0: $29.95; CD with paperback book, ISBN 978-1-4301-1087-3: $18.95

Gr 1-4 -- Leroy Paige was born into a poor family in Mobile, Alabama, around 1906. He earned the nickname "Satchel," while working at Mobile's train depot, carrying satchels for travelers. In his family of 12 children, money was always tight. A talented pitcher, he never considered baseball as a career until he landed in reform school for stealing. A coach suggested he focus on baseball; after that, there was no stopping him. His blend of talent and showmanship propelled him from semi-pro ball to stardom in the Negro Leagues to pitch in the newly integrated Major Leagues, earning a spot in Cooperstown's Baseball Hall of Fame. Baseball's greatest anecdotes usually have an air of tall-tale about them, and Satchel's winning ways and personality make for a biography that is as entertaining as fiction. Imagine facing his famous "bee ball," which would always "be" where he wanted it to be. Lesa Cline-Ransome writes in a folksy manner, and Dion Graham's relaxed Southern voice is a perfect complement, enhanced with sound effects and music. Though long on text, the book's large size and Graham's narration combine to offer children a chance to pore over visual details. Playing in the Negro Leagues was not always a bed of roses, but James Ransome's oil paintings highlight Paige's joi de vivre and joi de baseball. Page-turn signals are optional.

Gr 1-4 -- Leroy Paige was born into a poor family in Mobile, Alabama, around 1906. He earned the nickname "Satchel," while working at Mobile's train depot, carrying satchels for travelers. In his family of 12 children, money was always tight. A talented pitcher, he never considered baseball as a career until he landed in reform school for stealing. A coach suggested he focus on baseball; after that, there was no stopping him. His blend of talent and showmanship propelled him from semi-pro ball to stardom in the Negro Leagues to pitch in the newly integrated Major Leagues, earning a spot in Cooperstown's Baseball Hall of Fame. Baseball's greatest anecdotes usually have an air of tall-tale about them, and Satchel's winning ways and personality make for a biography that is as entertaining as fiction. Imagine facing his famous "bee ball," which would always "be" where he wanted it to be. Lesa Cline-Ransome writes in a folksy manner, and Dion Graham's relaxed Southern voice is a perfect complement, enhanced with sound effects and music. Though long on text, the book's large size and Graham's narration combine to offer children a chance to pore over visual details. Playing in the Negro Leagues was not always a bed of roses, but James Ransome's oil paintings highlight Paige's joi de vivre and joi de baseball. Page-turn signals are optional.

Copyright © 2012 Library Journals, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

I'm back after an awesome summer vacation and I think I did pretty good choosing this week's cutie, if I say so myself. What do you think?

T.J. Holmes is a former CNN anchor and correspondent. In 2011, he moved from CNN to BET. Four nights a week, you can enjoy his gorgeousness...uh, I mean his deep commentary on social issues African Americans face today.

Word to Describe: GORGEOUS!

By: shelf-employed,

on 1/26/2012

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

African Americans,

music,

history,

book review,

historical fiction,

dogs,

New Orleans,

J,

musicians,

hurricanes,

Hurricane Katrina,

Add a tag

Woods, Brenda. 2011.

Saint Louis Armstrong Beach. New York: Nancy Paulsen (Penguin Group)

It's hard to believe that I'm labeling a book about Hurricane Katrina "historical fiction," but to middle-grade readers, that's exactly what it is. While memories of Katrina are still fresh in the minds of New Orleans and Gulf Coast residents, 2005 is a lifetime ago for a 5th grader, born in 2001.

This first-person fictionalized account of 11-year-old Saint Louis Armstrong Beach (named for his grandfather King Saint and the famous trumpeter), tells the brief story of the run-up to Hurricane Katrina, the storm (in which he is trapped with an elderly neighbor), and its aftermath. With freakish good luck and a family with money and decent jobs, Saint will fare better than many, if not most, New Orleanians actually did. However,

Saint Louis Armstrong Beach: A Novel (a boy, a dog, and the hurricane that almost separated them) serves as an excellent middle-grade introduction to this important page in American history. The plight of the less fortunate provides a backdrop for Saint's story. When he wonders why others are not evacuating to shelter in other cities, his father reminds him that not all people

can leave,

"And who's gonna pay for that? Some people got no jobs, others got no money, and when I say no money ... I mean no money. Some people got nuthin' except the clothes on their backs, Saint."

"Money's real important, huh?"

"Yep, but what you do with it is even more important. Most a the people who claim money's not important are folks who have plenty of it. You remember that."

If it's a tad didactic and Saint is a tad too saintly, so be it. Sometimes we need the obvious lesson. A short (136 pages) and accessible book for young readers. Light on scientific information, pair this one with an appropriate nonfiction title.

Brenda Woods is a Coretta Scott King Honor Award winner for

The Red Rose Box.

Other reviews @

Kirkus ReviewsWaking Brain CellsBermuda Onion's WeblogTeachers, there's a

Reader's Companion for Saint Louis Armstrong Beach.

How Lamar's Bad Prank Won a Bubba-Sized Trophy by Crystal Allen 2011

How Lamar's Bad Prank Won a Bubba-Sized Trophy by Crystal Allen 2011

Favorite quote "But around two o'clock those curls droop and dangle as if Sergio's growing black noodles on his forehead and girls love that too. Once I tried some of that mousse stuff in my afro. I squirted a pile of that extra hold foam in my hand and rubbed it through my hair. For ten minutes, I waited for black noodles to dangle on my forehead. Instead my afro held an old-school slant as if me and Frederick Douglass had the same barber." Lamar pg. 24

Don't ask me why but the above quote tickled me pink, I actually burst out laughing. well ok, I know why. I've always been amused by Frederick Douglas's' hair, extraordinary guy, but oh man, that hair. *shakes head* Reminds me of Cornel West too. Anyway this book is about Lamar who is the baddest, maddest bowler at Striker's Bowling Paradise. He is King of Strikers. Sure Lamar is one of the best bowlers around, but he's not so great with girls, in fact he's constantly striking out with them. While Lamar is doing all his bowling, he also has to deal with his older brother, Xavier the Basketball Savior. Xavier is revered in their hometown of Coffin, Indiana and Lamar's father is quick to go to Xavier's basketball games and go over strategy with him, but it's been years since he bowled with Lamar. Lamar's tired of being ignored so when bad boy Billy Jenks invites him to take part in his bowling hustle, he accepts. Here's a way to make enough money doing something Lamar loves in order to buy a Pro Thunder (expensive pro ball) and maybe even impress his hero, famous bowler, Bubba Sparks. Oh and Lamar just may get the girl.

Some of the 'lingo' is rather cheesy in this book. In fact, at times it seemed outdated. On the very first page Lamar is listening to his best friend Sergio 'bump his gums'. I've never heard that expression before so I asked my dad who knows a lot of slang. He said that expression was older than he was (he grew up in the '80s), but hey, maybe it's popular in Indiana? There are a few other examples of really cheesy dialogue/comebacks but in the end, I think it all adds to Lamar's charm. I was amazed at Lamar's confidence, but being totally honest, it's not at all surprising. I think (for some reason) it's a lot less surprising to see a young and confident main character. In middle school, I think many guys think they are invincible, whereas many girls are a bit shyer. Regardless, Lamar reminded me of my brother and all the other young guys I know who love to trash talk. Although I did think Lamar's constant strutting was a bit much. The author juggles a lot of storylines and I do think the ball was dropped a few times. Each storyline is interesting and starts off well developed, but a couple were quickly wrapped up, much of the action occurring off the page (*cough* Sergio and Tasha *cough*). Lamar and his father clearly have issues they need to work out and everything seemed to get really happy really fast, but Lamar is just so gosh-darn adorable that you can't help but want him to have a cheesy ol' neat ending.

As you can probably tell, I love Lamar. I want to meet Lamar (actually I've already met Lamar and been annoyed by him but guys like Lamar seem less annoying in books). Lamar is one of the most well rounded characters I've come across. He has seriously debilitating asthma and he managed to tug at my heartstrings when he wanted to play soccer to impress a girl (Makeeda), but his doctor said that based on his health that was just not possible. I love soccer so I was able t

By: shelf-employed,

on 10/4/2010

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

trains,

inventions,

Non-Fiction Monday,

picture books for older readers,

Underground Railroad,

bio,

inventors,

E,

African Americans,

history,

nonfiction,

Add a tag

Kulling, Monica. 2010.

All Aboard! Elijah McCoy’s Steam Engine. Ill. by Bill Slavin. Ontario, CA: Tundra.

One of the things that I love about reviewing children’s nonfiction is the number of new things that I learn every day. Today I learned a little-known, but interesting and inspirational life story, as well as an interesting tidbit of etymology, the origin of the phrase “the real McCoy.”

Get on Board!

we hear our conductor

singing low

the song she uses

to let us know

now is the time

to get on board...

the midnight train

runs underground

we hide and pray

not to be found

we risk our lives

to stay on board...

So begins

All Aboard! But

All Aboard! is not the story of the Underground Railroad, rather it is the culmination of the Underground Railroad's greater purpose - a self-determined, productive life, lived out in freedom. Elijah McCoy was the son of slaves who escaped to Canada on the Underground Railroad. His determined and hardworking parents saved enough money to send Elijah to school overseas, where he studied to become a mechanical engineer.

He returned in 1866 to join his family in Michigan. Though he may have been free, his opportunities were not equal. Despite his education, he was only able to secure work as an "ashcat," feeding coal into the firebox of a steam engine for the Michigan Central Railroad,

What a letdown! Elijah knew engines inside and out. He knew how to design them. He knew how to build them. He also knew the boss didn't think much of him because he was Black. But Elijah needed work, so he took the job.

Still, Elijah persevered in his job while his mind, trained in engineering, sought to find a solution to the miserable job of "grease monkey," the boys (including Elijah) who oiled all of a train's gears when they frequently seized up due to friction and lack of lubrication. Trains of the time were typically stopped every half hour or so for greasing. After several years, Elijah invented (and patented) an oil cup, which was used successfully to keep the trains running. Travel by train became faster, safer, and more efficient. He continued to invent throughout his life, eventually filing 57 patents! Others tried to copy Elijah McCoy's oil cup, but none were able to match his success.

When engineers wanted to make sure they got the best oil cup, they asked for the real McCoy.

All Aboard! Elijah McCoy's Steam Engine is an obscure but inspiring story, made particularly poignant by the juxtaposition of his parents' Underground Railroad experience, and his own experience working for the Michigan Central Railroad. The dialogue is invented and there are no references cited, however, the engaging story is simply told in a manner that makes complex topics like the inventive process and racism accessible to young readers.

All Aboard! is short enough that it can easily be read aloud to a classroom or storytime for older children.

The book's pen and watercolor illustrations are colorful, and full of life and expression; the reverse side of the dust jacket doubles as poster. The cov

Full name: Renée Watson<?xml:namespace prefix = o ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" />

Full name: Renée Watson<?xml:namespace prefix = o ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" />

Birth date: July 29, 1978

Location: Paterson, NJ (But I grew up in Portland, Oregon)

Website/blog: http://www.reneewatson.net/

Genre: Children’s and Young Adult Literature

WiP or most recently published work:

Recently Published: A Place Where Hurricanes Happen and What Momma Left Me

Writing credits: Picture Book: A Place Where Hurricanes Happen (Random House, June 2010)

By: shelf-employed,

on 7/20/2010

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

war,

foster homes,

J,

Odyssey Award,

digital audiobook,

African Americans,

epistolary novels,

siblings,

peace,

book review,

family life,

disabilities,

Add a tag

Woodson, Jacqueline. 2010.

Peace, Locomotion. Read by Dion Graham. Brilliance Audio.

(about 2 hours on CD, mp3 download, or Playaway)

Peace, Locomotion continues the story of Lonnie Collins Motion (or Locomotion) first begun in

Locomotion. After their parents perished in a fire, Lonnie and his sister, Lili were sent to separate foster homes. Years have passed. Lonnie is now twelve and although they miss each other, both have settled in to their new homes.

Locomotion was a novel written in verse, as Lonnie learned the forms of poetry from a caring teacher.

Peace, Locomotion is an epistolary novel, consisting of letters from Lonnie to Lili as he endeavors to chronicle his feelings, his memories of their earlier life together, and the daily occurrences of his new life. He saves the letters in the hope that when he is someday reunited with Lili, he can relive and share with her each day that they were apart. He struggles with the fact that his younger sister begins to call her foster mother, Momma, and can barely remember their parents. One of his friends is moving away, his teacher is mean, and he does poorly on tests and homework. At home, he has another problem. One of his foster mother's sons is serving in the war (the listener does not know if it is the war in Afghanistan or Iraq) and things are not going well. Lonnie is tempted to pray for Jenkins' safe return but his foster brother Rodney suggests that he pray for peace instead - explaining, if peace comes, all things will follow. In spite of the many obstacles that life has placed in Lonnie's path, he remains positive and thoughtful, never quick to draw conclusions or pass judgment. He finds joy in a church choir, a snowball fight, a good friend. He is kind and wise beyond his years. Although this is a story about African American families, it could be about any family in similar circumstances. It is a story about hope and family and finding peace wherever one may.

The challenge of narrating a novel consisting of letters from only one person is a great one, and Dion Graham's reading rises to the test. He is superb. Graham perfectly captures the many moods of Lonnie Collins Motion with precision, never exaggeration. The listener can hear a smile begin to spread across Lonnie's lips, tears well up in his eyes, a sparkle light up his face. Lonnie recounts conversations within his letters, allowing Graham to create character voices of Lili, Lonnie's friends, and his foster family; but Locomotion is the star of this novel and all ears are upon him. Highly recommended for middle grades.

Peace, Locomotion was named a

2010 Odyssey Honor Audiobook, and was named to

ALSC's 2010

Notable Children's Recordings.

Listen to an excerpt here.Penguin Young Readers offers a free downloadable discussion guide.

0 Comments on Peace, Locomotion as of 1/1/1900

By: shelf-employed,

on 6/26/2010

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

book review,

historical fiction,

family life,

California,

mothers,

Civil Rights,

sisters,

prison,

J,

1960s,

poverty,

Black Panthers,

African Americans,

Add a tag

If you haven't heard of

One Crazy Summer, you will. Rita Williams-Garcia's latest middle grade fiction is getting a lot of buzz, and justifiably so.

One Crazy Summer is set in a poor neighborhood of Oakland, California, 1968. Delphine, Vonetta, and Fern (three African-American girls, aged 11, 9 and 7) travel on their own from Brooklyn to Oakland. Their father, against the judgment of the girls' grandmother and caretaker, Big Mama, has decided that it's time for the girls to meet Cecile, the mother that deserted them. With visions of Disneyland, movie stars, and Tinkerbell dancing in their heads, they set off on the plane determined not to make, as Big Mama says, "Negro spectacles" of themselves. This is advice that Delphine, the oldest, has heard often. She is smart and savvy with a good head on her shoulders, and she knows how to keep her sisters in line. Not much can throw her for a loop, but then, she hasn't met crazy Cecile yet. Cecile, or Nzila, as she is known among the Black Panthers, is consumed by her passion - poetry. She writes powerful and moving poems for "the people" - important work, and she is not about to be disturbed by three young girls and their constant needs for food and attention. She operates a one-woman printing press in her kitchen - no children allowed. Instead of Disneyland and the beach, she shoos the girls off daily to the local center run by the Black Panthers. There, in the midst of an impoverished, minority neighborhood, the girls receive free breakfast, kind words, and an education the likes of which they would never have gotten in Brooklyn. Slowly, they begin to understand the plight of "the people" - the Blacks, the poor, the immigrants, even Cecile.