Previous parts of this interview: Part I – Steve Moore, River of Ghosts, The Show, and Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, and Part II – Punk Rock, Crossed, and Providence. Now read on…

PÓM: A few other things… Yes, now. Have you been following any of the latest revelations on Jack the Ripper? Do you keep an eye on that?

PÓM: A few other things… Yes, now. Have you been following any of the latest revelations on Jack the Ripper? Do you keep an eye on that?

AM: [Laughs] No, because it’s all going to be bollocks.

PÓM: Oh yeah.

AM: Alright, I stand to be corrected, but what are the latest revelations on Jack the Ripper?

PÓM: Somebody claimed to have bought a scarf, a very expensive scarf…1

AM: Oh yeah, I read about that. And obviously at the time, that’s bollocks…

PÓM: Oh yes, absolutely and complete bollocks!

AM: And they’ve since proved that it’s bollocks – I think that they’ve just said that, no, there’s no connection at all between Catherine Eddowes and the stain on this scarf.

PÓM: I do remember thinking that they seemed to be in possession of an awful lot of information about DNA and all of that that seemed… unlikely.

AM: Unlikely at the time, yes. No no, that – these are always going to be non-starters. Alright, unless there is some brilliant piece of evidence waiting to be discovered that – how likely is that?

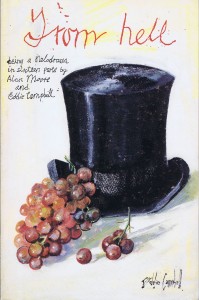

PÓM: I know. I just wondered if – ‘cause you did From Hell, I presume you still have some interest in the subject.

AM: Well, with From Hell, at the end of it, in The Dance of the Gull Catchers, there is that statement about – Look, how long can this go on? About Koch’s Snowflake2, about the increasing trivia applied around the crinkly edges of this case, but the area of the case cannot exceed the original events and consequently, new books about Jack the Ripper, they’re less about Jack the Ripper than they are about keeping the Jack the Ripper industry going, because it’s been quite lucrative for a few years, you know? And I honestly think that that is the truth.

AM: Well, with From Hell, at the end of it, in The Dance of the Gull Catchers, there is that statement about – Look, how long can this go on? About Koch’s Snowflake2, about the increasing trivia applied around the crinkly edges of this case, but the area of the case cannot exceed the original events and consequently, new books about Jack the Ripper, they’re less about Jack the Ripper than they are about keeping the Jack the Ripper industry going, because it’s been quite lucrative for a few years, you know? And I honestly think that that is the truth.

So, no, I tend to be dismissive of – every four or five years there will be ‘At last, the final truth!’ And it never is. And it’s very often preposterous, or a deliberate hoax. Or you’ll get, say, Patricia Cornwell, with her vandalisation of a Walter Sickert painting in the ridiculous hope that she could match the DNA to that on the letters received the police, which were not from the killer anyway.3

PÓM: I remember when the documentary was on the telly, I saw it was coming up…

AM: Yeah, I saw that, and I saw at the end of it, all she’d got was some footage of Walter Sickert being led out, probably in his eighties, to be filmed in a garden somewhere, and she said, ‘Yes, look at those eyes – pure evil.’ Ignorant woman.

PÓM: I remember she said something like ‘I knew as soon as I looked into his eyes that it had to be him.’4 And this is a woman who…

AM: That was all the evidence that she’d got, and – the thing is, that Patricia Cornwell is apparently supposed to be an actual real-life pathologist…5

PÓM: Yeah!

AM: …apparently cases in the American legal system have presumably depended upon her evidence – I hope she was doing a little bit more than looking in people’s eyes.

PÓM: I know! I have never been so disappointed with something on the television – in my life! Because I expected – because of who she was, and what she was, I expected this was going to be really incisive and good and interesting.

AM: I had read some of her books, so perhaps I wasn’t expecting quite as much as you were.

PÓM: [Laughs] Fair enough!

AM: I read a few of her books with the beautiful woman pathologist…6

PÓM: Oh, I know who you mean…

AM: …who somehow always ends up at the centre of every case. She’s always the one that the serial killer gets an obsession with, even though there’s no way in the real world that he would ever know who she was. She’s always smarter than the police. And then when I found out that Patricia Cornwell was herself a pathologist at some point I thought, ‘Yes, I think I can see where this is going.’

PÓM: Yes. It did seem as well the whole Jack the Ripper thing was kind of because her father had left home when she was five, and there were some elements of that in there, which is where it started getting strange.

AM: Yeah, well a lot of these people who get obsessed with true crimes, they’re – sometimes, they can be working out something in their own psychology, rather than anything to actually do with the crime that they are officially dealing with. I haven’t really taken a great deal of interest in Jack the Ripper since finishing From Hell – probably more in Psychogeography and London.

PÓM: I must say, we’ve been spending a fair bit of time in London, Deirdre and myself. We were over there last week. We went to see – do you know the Reverend Richard Coles?7

PÓM: I must say, we’ve been spending a fair bit of time in London, Deirdre and myself. We were over there last week. We went to see – do you know the Reverend Richard Coles?7

AM: Oh yes, I met him once. I met him with Robin Ince.8

PÓM: Yeah. He was doing a thing in the British Library, he was doing – because he’s got a first volume of his autobiography out – another good Northampton lad!

AM: Is he? Yeah, he’s from out in the outskirts, I think he’s from one of the villages.

PÓM: That’s where he’s being a Rev these days. A thoroughly lovely man.

AM: He seemed really nice when I met him, and of course he was great in The Communards.

PÓM: Well, he was. He was. Not a great dancer, but a charming human being. But, yeah, I’ve recently joined the British Library, which is completely fantastic.9 I’m doing research into Flann O’Brien, and The Cardinal and the Corpse, all of that.

[There’s actually a part of the interview missing here, because I felt it was so far removed from having even the slightest relevance to this particular site that it was best elsewhere. It concerns English writer Iain Sinclair‘s 1992 documentary film The Cardinal and the Corpse, which almost no-one has seen besides Alan and myself. It also peripherally concerns Irish writer Flann O’Brien, about whom I have been spending quite a lot of time reading and researching of late. The interview is here, on the gorse website. By absolutely no coincidence whatsoever I have an essay on Flann O’Brien in gorse #3, entitled The Cardinal & the Corpse, A Flanntasy in Several Parts, which I commend to you all. End of outrageous and gratuitious self-promotion.]

[There’s actually a part of the interview missing here, because I felt it was so far removed from having even the slightest relevance to this particular site that it was best elsewhere. It concerns English writer Iain Sinclair‘s 1992 documentary film The Cardinal and the Corpse, which almost no-one has seen besides Alan and myself. It also peripherally concerns Irish writer Flann O’Brien, about whom I have been spending quite a lot of time reading and researching of late. The interview is here, on the gorse website. By absolutely no coincidence whatsoever I have an essay on Flann O’Brien in gorse #3, entitled The Cardinal & the Corpse, A Flanntasy in Several Parts, which I commend to you all. End of outrageous and gratuitious self-promotion.]

PÓM: Are you doing some series of things with Joyce Brabner?10

AM: There is a work that I’m – I’m doing a work with Joyce, but I’m starting that at the moment. I can’t tell you much about that, because it will be sometime this year – I’m more or less starting work on it now, over the next – probably over the weekend, and it’s likely to be something to do with identity, but I really can’t tell you much more than that – I’ve got my ideas, but they’re not really well formed enough yet, but later in the year I’ll be able to fill you in more with that.

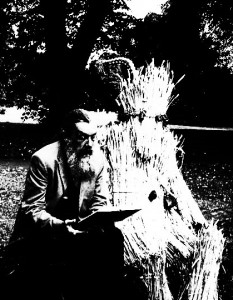

PÓM: Ok, cool. Sure, we’ll talk again, undoubtedly. And I think I’m going to wrap it up – I must say, when you’re talking about doing Swandown, and things like that – that’s the thing with the pedalo, isn’t it? With the swan-shaped pedalo?11AM: That is one of the sweetest films I’ve ever seen, and not just because I’m in it. In fact, I think that my contribution is one of the more negligible aspects of it. It’s English poetry. It shows you that there is no landscape that cannot be made poetic with the addition of a big plastic swan. And in fact, since then I also earlier this year – no, last year, last year. Spring or Summer, I went and filmed a bit with Andrew and Iain for their next project, which is called By Our Selves, and it’s all about John Clare12, and it’s got Andrew mucking about dressed as a straw bear, and recreating John Clare’s limping walk from Epping Forest and Matthew Arnold’s mental asylum back to Helpston in Northampton. Eighty miles or something, where he was eating grass and hallucinating. Yeah, so Andrew and Iain came up to Northampton, I spent a lovely afternoon sitting pretending to be a version of John Clare. They’ve got Toby Jones

13 doing all the heavy lifting in terms of being John Clare, so that should be – ‘cause he’s an incredible actor…

Alan Moore and a Straw Bear, borrowed from here

AM: That stuff is the best. Things like that that just come out of the blue. I still enjoy me comics work, I still enjoy the ordinary writing that I do, but – the little surprising things like that, that I’ve not done before, that are a great afternoon out, seeing lovely people, and knowing that it’s going to end up as a really poetic cinematic document, yeah, I am having a lot of fun with that, when it happens. It’s irregular, but charming when it does.

PÓM: Well, good. And I think that’s it. Is there anything that you’re doing that I should know about that I don’t know about?

AM: Yeah, probably. Whether I actually consciously know about it, is the big question. There must be some – did you hear about The Dying Fire?

PÓM: Nooooo…

AM: This was a book that I’ve just brought out from Mad Love Publishing, it’s the collected poetry of Dominic Allard…14

PÓM: Yes, I did, because I have a copy inside. Yes, of course.

AM: Ah right. With the big introduction. That seems to be going quite well, and Dominic seems a bit stupefied by the sudden exposure – mind you, Dominic seems a bit stupefied by most things, it has to be said. But, no, that was really good, taking the books down to him, and giving him a load of copies, so there’s that. What else have I been doing? I’ve been reading through Steve Moore’s journals, which I collected from his house, and that’s bittersweet. There’s some incredible information in there, things that I’d forgotten about. Just day-by-day stuff in Steve’s life, but he was meticulous about listing it all.

AM: Ah right. With the big introduction. That seems to be going quite well, and Dominic seems a bit stupefied by the sudden exposure – mind you, Dominic seems a bit stupefied by most things, it has to be said. But, no, that was really good, taking the books down to him, and giving him a load of copies, so there’s that. What else have I been doing? I’ve been reading through Steve Moore’s journals, which I collected from his house, and that’s bittersweet. There’s some incredible information in there, things that I’d forgotten about. Just day-by-day stuff in Steve’s life, but he was meticulous about listing it all.

PÓM: Do you do that? Do you keep a journal, or anything like that?

AM: No I don’t. And Steve’s journals are part of the reason why I don’t.

PÓM: Oh yes, one other thing I did want to ask you. Do you remember our last interview? That was the written interview.15

AM: Yes…?

PÓM: Did you ever get any feedback on that, or did you hear – there was a certain amount of…

AM: I don’t know if I did or not, Pádraig. Where would I have got it from?

AM: Well, indeed. There was huge amounts of hoopla on the internet about it, which – it was interesting. It was…

AM: Oh, that was the stuff about the Golliwogg?

PÓM: Yes, the Golliwogg, and…

AM: Yes, that was when I wrote my – Yes, I remember – that was when I spent the Christmas writing the rejoinder?

PÓM: Yes, yes!

AM: Yeah, I didn’t hear much about it, to tell the truth, once I’d got it out of me system, and I thought that the issues had been addressed, I just kind of let it go. Why, did – you say that there was a lot of furore?

PÓM: Oh, I had – when I put it up on my blog, and it just spread out everywhere, and I was getting hundreds of comments and replies. It was all quite fascinating – it genuinely didn’t bother me in any way, shape, or form. The people who said rude things, I just deleted them, because people have strange notions about what the right to free speech actually means. And it was just – it was interesting – it was great. It was a fantastic piece of, em…

AM: Invective?

PÓM: I was going to say a fantastic piece of writing, of a thing to put out there, and I was delighted to be in that way involved with it but, yes, a fine piece of invective, and all the better for it.

AM: I was talking with somebody who read it, and he was saying ‘I think you might have revived a kind of literary form, that has not been really practiced since the eighteenth century,’ the really crushing, bitter, stinging satire, if you will. Yeah, I was quite pleased with it. After doing it, I tended to put it out of me mind.

PÓM: No harm in that. I must say…

AM: Was any of the response positive?

PÓM: Oh yeah! Oh Christ, yes! Plenty of it. There was lots of people who are just happy to do down anything that turns up, but there was a lot of people that thought you gave someone a kickin’ that deserved a kickin’.

AM: Well, that’s good. I had a very nice comment from Ramsey Campbell16. He said, pretty much, ‘Right on, Alan,’ so that was nice. I did see, in the Michael Moorcock issue of Locus that came out recently that Mike, he was talking a little bit about Grant Morrison as well, just because he was asked some question about why he doesn’t encourage other people to do Jerry Cornelius stories these days, which apparently does rather connect up with some of Morrison’s work. Ah, I thought it needed saying, and it was better out than in.

AM: Well, that’s good. I had a very nice comment from Ramsey Campbell16. He said, pretty much, ‘Right on, Alan,’ so that was nice. I did see, in the Michael Moorcock issue of Locus that came out recently that Mike, he was talking a little bit about Grant Morrison as well, just because he was asked some question about why he doesn’t encourage other people to do Jerry Cornelius stories these days, which apparently does rather connect up with some of Morrison’s work. Ah, I thought it needed saying, and it was better out than in.

PÓM: Well, indeed. Sure, it’s all part of life’s rich pageant.

AM: Absolutely.

AM: Mel’s fine – oh, yes, that’s something that I should probably tell you about. Mel is preparing for her first spectacular exhibition. This will be at the Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury.

PÓM: Oh, I love Bloomsbury, I have to say. I could live in Bloomsbury.18

AM: Have you been to the Horse Hospital?

PÓM: I don’t think we have, no.

AM: Well, I did a gig there with the lovely Kirsten Norrie19 – which also, she appears with me in that, By Our Selves, the John Clare film. But I did a gig where Kirstin was singing, and I was reading a part of Jerusalem, so I went to the Horse Hospital, and in there, I knew that our gig was underground, in the basement, and I thought, ‘Oh, this is a bit weird, there’s no stairs, there’s just these ramps.’ And then I thought ‘Horse Hospital!’

But it’s a lovely little space, and I believe that Mel will be doing her exhibition there on April the 10th, and there’s tons and tons of drawings, there’s seven or eight of her paintings, and I believe that there might be some bronze busts that she’s done of the three main characters from Lost Girls. So, if anyone reading this happens to be in the Bloomsbury area around April 10th this year, they could do worse than to drop in.

PÓM: I shall be sure to tell people.

AM: OK, you take care, like I say, Pádraig, and love to Deirdre – and that’s what Mel’s doing, she’s preparing that.

FOOTNOTES:

1On the 6th of September 2014 the Daily Mail carried a story that DNA evidence had been found on a scarf – allegedly once the property of Catherine Eddowes, the fourth of the five ‘canonical’ victims of the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, whose exploits set Victorian London into a frenzy of speculation which has still not died away – which proved that the killer was actually Polish immigrant Aaron Kosminski. The story is here, although you really also need to read the refutation, here, as well.

2I refer you to the Koch’s Snowflake page on Wikipedia, because they explain it better than I ever will.

3Crime writer Patricia Cornwell wrote a book called Portrait of a Killer — Jack the Ripper: Case Closed, published in 2002, where she claimed that British painter Walter Sickert was the Whitechapel murderer, and went to extraordinary – and, frankly, borderline insane – lengths to prove it, including supposedly cutting up one of his paintings in an effort to find clues of some kind. There’s an excellent piece about it on the Casebook: Jack the Ripper website, here. In the meantime, Cornell has written more on the subject, a Kindle Single called Chasing the Ripper, published in 2014, and available here, if you’re feeling brave.

3Crime writer Patricia Cornwell wrote a book called Portrait of a Killer — Jack the Ripper: Case Closed, published in 2002, where she claimed that British painter Walter Sickert was the Whitechapel murderer, and went to extraordinary – and, frankly, borderline insane – lengths to prove it, including supposedly cutting up one of his paintings in an effort to find clues of some kind. There’s an excellent piece about it on the Casebook: Jack the Ripper website, here. In the meantime, Cornell has written more on the subject, a Kindle Single called Chasing the Ripper, published in 2014, and available here, if you’re feeling brave.

4 Yes, she really says something almost exactly like that. Here‘s the relevant bit from the documentary, courtesy of those nice people over at YouTube.

5Patricia Cornwell isn’t actually a ‘real-life pathologist,’ although she did work in the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of Virginia for six years, first as a technical writer and then as a computer analyst, so had at least some input into their findings, one imagines.

6Dr Kay Scarpetta, the protagonist of twenty-two Cornwell novels thus far.

7The Reverend Richard Coles is a Church of England priest, currently working as the parish priest of St Mary the Virgin, Finedon, Northampton, in the Diocese of Peterborough. He was previously in The Communards with Jimmy Somerville, formerly of The Bronsky Beat, with whom Coles had also occasionally played. He is openly gay and lives with his civil partner in a celibate relationship, although they have four dachshunds, and he remains the only vicar in Britain to have had a Number 1 hit single. Above and beyond all that, he does regular appearances on the television and radio in Britain, and is a thoroughly lovely human being. He did an appearance in the British Library on Friday the 20th of February 2015 to publicise his autobiography, Fathomless Riches, which I attended with my wife Deirdre.

7The Reverend Richard Coles is a Church of England priest, currently working as the parish priest of St Mary the Virgin, Finedon, Northampton, in the Diocese of Peterborough. He was previously in The Communards with Jimmy Somerville, formerly of The Bronsky Beat, with whom Coles had also occasionally played. He is openly gay and lives with his civil partner in a celibate relationship, although they have four dachshunds, and he remains the only vicar in Britain to have had a Number 1 hit single. Above and beyond all that, he does regular appearances on the television and radio in Britain, and is a thoroughly lovely human being. He did an appearance in the British Library on Friday the 20th of February 2015 to publicise his autobiography, Fathomless Riches, which I attended with my wife Deirdre.

8Robin Ince is an English Science-Comedian and renowned Atheist. He is involved with the occasionally annual Christmastime event Nine Lessons and Carols for Godless People, as well as the radio programme The Infinite Monkey Cage, both of which have included Alan Moore on occasion.

9If you think I’m being overly mean in describing the Rev. Coles as a bad dancer, I suggest you go look at this video of The Communards performing Never Can Say Goodbye

, and make up your own mind. The British Library, by the way, is one of my favourite places in the whole wide world. If Heaven is not very like it, I shall be very disappointed. 10Joyce Brabner is an American comics writer, and the widow of the late Harvey Pekar. She has collaborated with Moore before, on Brought to Light, and on Real War Comics. Most recently she has written the non-fiction graphic novel Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague, about the real-life efforts of people caught up in the AIDS epidemic in New York in the early 1980s. It’s good stuff, and you all need to go read it.

10Joyce Brabner is an American comics writer, and the widow of the late Harvey Pekar. She has collaborated with Moore before, on Brought to Light, and on Real War Comics. Most recently she has written the non-fiction graphic novel Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague, about the real-life efforts of people caught up in the AIDS epidemic in New York in the early 1980s. It’s good stuff, and you all need to go read it.

11Swandown is a 2012 film in which Andrew Kötting and Iain Sinclair pedaled a swan pedalo down the Thames from the Hastings, on the sea, to Hackney, in London, occasionally joined by people like Alan Moore and comedian Stewart Lee. Look, I promise I’m not making this stuff up, and there’s a photograph to prove it. From left to right we have Lee, Moore, Kötting, and Sinclair.

11Swandown is a 2012 film in which Andrew Kötting and Iain Sinclair pedaled a swan pedalo down the Thames from the Hastings, on the sea, to Hackney, in London, occasionally joined by people like Alan Moore and comedian Stewart Lee. Look, I promise I’m not making this stuff up, and there’s a photograph to prove it. From left to right we have Lee, Moore, Kötting, and Sinclair.

12John Clare, known as The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet, was the writer of collections like Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery and Village Minstrel and other Poems. The film By Our Selves is in part based on Iain Sinclair’s book The Edge of the Orison: In the Traces of John Clare’s ‘Journey Out of Essex’. More information can be found on the By Our Selves Kickstarter page. It was successfully funded, and the project is ongoing.

13Toby Jones is an excellent English actor. Amongst other things, he has done the voice of Dobby the House Elf in the Harry Potter films, appeared in an episode of Doctor Who, and had parts in films like Captain America: The First Avenger, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Hunger Games, and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and many many more.

13Toby Jones is an excellent English actor. Amongst other things, he has done the voice of Dobby the House Elf in the Harry Potter films, appeared in an episode of Doctor Who, and had parts in films like Captain America: The First Avenger, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Hunger Games, and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and many many more.

14Mad Love Publishing is a publishing company Moore set up in the late 1980s with others, originally to publish AARGH (Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia), and subsequently the first two issues of Big Numbers. The company had a long hiatus, but has reappeared recently as the publisher of Dodgem Logic, and most recently of The Dying Fire, a poetry collection by Moore’s old school friend Dominic Allard. The Northants Herald & Post reported on the story here.

15The interview referred to hear, which Alan doesn’t at first realise I’m referring to, is the infamous Last Alan Moore Interview?, which some of you may have already read, or at least read about. It has, to date, a bit over 100,000 views, and 350 replies, which is not too bad for the first post on a new blog!

16Ramsey Campbell is an English horror writer who has written numerous novels, including The Doll Who Ate His Mother, The Face That Must Die, and The House on Nazareth Hill, as well as numerous collections of short stories. He has a list of awards for his work as long as your arm, including the British Fantasy Award, the World Fantasy Award, the International Horror Guild Award, and the Bram Stoker Award.

16Ramsey Campbell is an English horror writer who has written numerous novels, including The Doll Who Ate His Mother, The Face That Must Die, and The House on Nazareth Hill, as well as numerous collections of short stories. He has a list of awards for his work as long as your arm, including the British Fantasy Award, the World Fantasy Award, the International Horror Guild Award, and the Bram Stoker Award.

17Melinda Gebbie is an American comics creator, now settled with her husband, Alan Moore, in the heart of England. They’ve worked together on various things, including Lost Girls.

18Bloomsbury is the bit of London that contains the British Museum, occasional headquarters of the Victorian version of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and the British Library. It’s full of culturally wonderfully stuff, parks with friendly squirrels in, and lots of Blue Plaques to all sorts of writers and the like. I recommend you go visit, at least once in your life. The exhibition in the Horse Hospital runs until the 9th of May, so there’s time to see it yet.

19Kirsten Norrie is a Scottish artist and musician, and a member of Wolf in the Winter, an international performance collective.

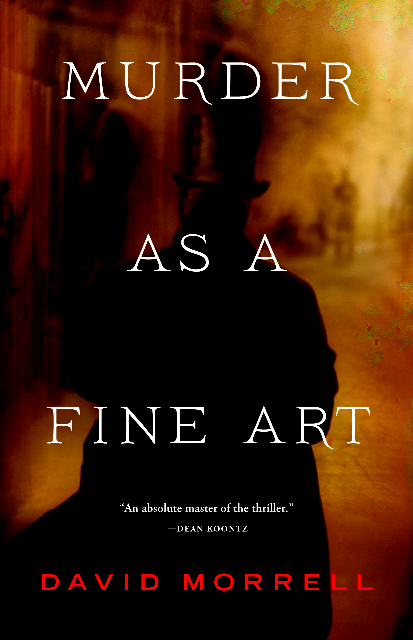

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

I had fun reading the interview. It’s very interesting. Great!

With all these Alan Moore interviews that have been done I wonder why no one will ask him why the big reveal behind Jack The Ripper in FROM HELL is exactly the same as the reveal in the 40 year old Sherlock Holmes movie MURDER BY DECREE. It isn’t just similar or kind of the same, it is exactly the same.

I find it funny how internet wen crazy over that older Moore interview and he barely recalls doing it in the first place.