Continuing on from yesterday's post about Amit Chaudhuri's A Strange and Sublime Address (a novella included in the collection Freedom Song), here's a bit more academic writing about the book. This time, my goal is to undermine, or at least question, the common opposition of Chaudhuri's "realism" to Salman Rushdie's "magical realism". The two writers have frequently been set against each other as polar opposites, but my argument here is that they have far more in common than might be obvious at first...

In his 2009 essay “Cosmopolitanism’s Alien Face”, Amit Chaudhuri tells of a conversation he had with the Bengali poet Utpal Kumar Basu:

We were discussing, in passing, the nature of the achievement of Subimal Misra, one of the short-story writing avant-garde in 1960s Bengal. ‘He set aside the conventional Western short story with its idea of time; he was more true to our Indian sensibilities; he set aside narrative’, said Basu. ‘That’s interesting’, I observed. ‘You know, of course, that, in the last twenty years or so, it is we Indians and postcolonials who are supposed to be the storytellers, emerging as we do from our oral traditions and our millennial fairy tales’. ‘Our fairy tales are very different from theirs’, said Basu, unmoved. ‘We don’t start with, “Once upon a time”.’ (91-92)Chaudhury goes on to explore the implications of this statement, and of the desire to solidify an idea of pure cultural identity (“Our fairy tales … We don’t start with…”) against ideas of modernism and cosmopolitanism, but here I would like to take the statements in the above paragraph more on their surface and to explore the effect of the stated and implied Once upon a time…

Salman Rushdie’s Shame does not begin with exactly those words, but the sense of a fairy tale beginning is strong: “In the remote border town of Q., which when seen from the air resembles nothing so much as an ill-proportioned dumb-bell, there once lived three lovely, and loving, sisters.” The narrator quickly assumes the role of storyteller: “…the three sisters, I should state without further delay, bore the family name of Shakil…” (3), the narrative voice here asserting, for the first of many times in Shame, the kind of presence that most European novels of the 19th century sought to vanquish in the name of realism.

The idea of realism led to third-person narratives unburdened by the presence of a narrator, and the success of that style has created a sense that storytelling was a more primitive tradition, a tradition that the 19th Century European novel first refined and then progressed beyond. The realist European novel is inextricable from a particular idea of European progress, and the aesthetic is strongly located within a specific, and quite narrow, time and place. Storytelling may be universal, written narrative may have a long and multicultural history, but the realistic novel is a particular technology.

The first sentences of Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address draw from that technology: “He saw the lane. Small houses, unlovely and unremarkable, stood face to face with each other.” The narration is submerged within the perception of the character, and in these first lines we don’t even know the character’s name — the character is nothing but a gendered pronoun, and the normal, sense-making syntax of noun followed by pronoun is reversed (there is no antecedent). The first name we encounter is not that of the viewpoint character, but rather what the viewpoint character sees: “Chhotomama’s house had a pomelo tree in its tiny courtyard and madhavi creepers by its windows.” Here, the unnamed viewpoint character possesses knowledge that is not allowed to readers: Who is Chhotomama? How do we know it’s Chhotomama’s house? We begin in medias res, but not so much in the middle of events as in the middle of perceptions. Perceptions are foregrounded, and we, the outside observer, build our knowledge from them. Only once we have perceived can we be provided with even some of the necessary information for ordinary meaning to be possible, but the importance of that information is de-emphasized: our viewpoint character’s name doesn’t appear until a parenthetical remark in the final sentence of the first paragraph: “A window opened above (it was so silent for a second that Sandeep could hear someone unlocking it) and Babla’s face appeared behind the mullions” (7). The technology of the realistic novel doesn’t require this technique; the technique emphasizes a decisive rejection of the storytelling tradition. Not only is there no narrating “I” situating the reader in relationship to the tale, but there is a determined lack of information about the character.

The first paragraph of A Strange and Sublime Address thus forces readers to make connections and draw conclusions, to connect that first “He” to “Sandeep”, while also showing us what may matter in the novel and what may not. Where Shame emphasizes storytelling, A Strange and Sublime Address emphasizes perception. The apparently radical differences between the two books — and the ostensibly opposite aesthetic approaches of Rushdie and Chaudhuri — diminish if we look at the novels’ types of storytelling and thus analyze both texts as metafictions that take different paths to similar conclusions about history, place, and representation.

Saikat Majumdar applies Walter Benjamin’s concept of the flâneur to Chaudhuri, but here we might draw on some other of Benjamin’s ideas, these from the 1936 essay “The Storyteller: Observations on the Works of Nikolai Leskov”, particularly section XVI, in which Benjamin writes of fairy tales:

The fairy tale tells us of the earliest arrangements that mankind made to shake off the nightmare which myth had placed upon its chest. … The liberating magic which the fairy tale has at its disposal does not bring nature into play in a mythical way, but points to its complicity with liberated man. A mature man feels this complicity only occasionally — that is, when he is happy; but the child first meets it in fairy tales, and it makes him happy. (157)This view of the fairy tale as a tool for liberation from myth is one that aligns well with Shame, but it’s harder to locate the engines of “Once upon a time…” within A Strange and Sublime Address, despite that novel mostly being presented through the point of view of a child. To find the fairy tale, we must locate the pedagogical imperative of the text. Benjamin concludes: “…the storyteller joins the ranks of the teachers and sages. He has counsel — not for a few situations, as the proverb does, but for many, like the sage. … The storyteller is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself” (162). Chaudhuri clearly wants to teach readers something about perception, materiality, and history, and his writing is determinedly anti-mythic. Further, the novel is strongly concerned with how stories represent the world, and how language and perception intertwine in narrative, which is why I call it a metafiction. To limn the liberatory magic of A Strange and Sublime Address, though, we should begin with the more obvious metafiction of Shame.

Though Chapter 1 of Shame is filled with asides from the narrator, it is Chapter 2 that truly breaks out of the established narrative, bringing us into a more recognizable reality with the first sentence: “A few weeks after Russian troops entered Afghanistan, I returned home, to visit my parents and sisters and to show off my firstborn son” (19). The narrative voice here is more straightforward and unified, and the details fit Rushdie’s known biography to such an extent that some readers and critics have confidently asserted that the voice is Rushdie. It is problematic to associate the writer with a textual effect in any book, and especially so in a book as wild, imaginative, and concerned with questions of history, identity, and representation as Shame, so here I will simply call this Voice 2, as opposed to the narrator of the more obviously fantastical sections, Voice 1.

Voice 2 is intimately related to Voice 1, however, and may logically be seen as the creator of Voice 1 (“I tell myself this will be a novel of leavetaking…” [22]). Voice 2 is an explainer and a ruminator, and the Voice 2 sections read like personal essays. But the genre (or mode) of the novel is remarkable in its ability to contain and recontextualize other genres (and/or modes) — the personal essay becomes embedded within the novel, and so its identity as an essay can no longer be trusted, because it is being put to use for novelistic purposes. It is thus rendered impure, and in a novel about impurities of identity and the translation of being and substance. “I, too, am a translated man,” Voice 2 says. “I have been borne across” (23), and this translation, this bearing across, is as true for the voice’s genre as for the character evoked by that voice.

The problem for Voice 2 is that the storytelling force of Voice 1 comes from a different age and place, and translating the form and tendencies of old aesthetics is, like all translation, a process that deforms and reforms the original, skewing the results. Even if the original could be moved perfectly into a new time and place, the result would still get skewed, as Borges proposed with Pierre Menard’s Quixote. Voice 2 must break in because Voice 1 is inevitably doomed to fail — or, if not fail exactly, to sputter unforseen effects all over the page. Voice 2 is forced to acknowledge this late in the novel:

I had thought, before I began, that what I had on my hands was an almost excessively masculine tale, a saga of sexual rivalry, ambition, power, patronage, betrayal, death, revenge. But the women seem to have taken over; they marched in from the peripheries of the story to demand the inclusion of their own tragedies, histories and comedies, obliging me to couch my narrative in all manner of sinuous complexities, to see my “male” plot refracted, so to speak, through the prisms of its reverses and “female” side. It occurs to me that the women knew precisely what they were up to — that their stories explain, and even subsume, the men’s. (180-181)Voice 2 here blames the failures and fragmenting of Voice 1 (or, perhaps, Voice 1-1.∞, as the possible voices within Voice 1 are infinite) on “the women”, thus giving the characters an autonomy that might be better ascribed to aesthetic and ideological forces rather than to a plane of reality in which the characters are real people and not textual figures. (Voice 2 is a textual effect that ascribes blame to other textual effects for the shape of the narrative.) We might more productively say that the phantasmagoria is overtaken by what resists fantasy — the factitious overcome by the factual.

This would seem to be a triumph of realism over fantasy, but that would only be true if the fantasy were wiped out, and it is not. The majority of Shame remains phantasmagoric, but differently so, and differently in multiple ways. The reader cannot erase the knowledge of Voice 2 within Voice 1, and so, from Chapter 2 on, we read the phantasmagoria differently than we might were Voice 2 never introduced. Were the book only to include Chapter 1, we could assume a unity to Voice 1 as, simply, the narrator. The introduction of Voice 2 in Chapter 2 offers the reader another hypothesis: Voice 1 is really Voice 2, the controlling power from our own recognizable reality. Passages such as the one quoted above, though, demonstrate that Voice 1 is not entirely controlled by Voice 2, and that, rather than a single narrator, it should be perceived as an assemblage of narrators. As a textual function, then, Voice 1 is plural (though its plurality is often indeterminate) and Voice 2 is singular.

The passage I quoted above begins with the crucial phrase that is missing from the first paragraph of the novel: “Once upon a time there were two families, their destinies inseparable even by death” (180). That could have been the first sentence of the book, but instead Voice 1 fumbled around a bit more. By here, Once upon a time can begin the section, but the section it begins is one about liberation. We have located the liberatory magic. Once upon a time there were “destinies inseparable even by death”, but the past of this tale may not be — or may not have to be — the present of this novel.

We have here located what Fredric Jameson has recently called “the antinomies of realism”. Jameson’s dialectical approach sets the récit against the roman, the tale against the novel, with the récit as, philosophically, a narrative form based on ideas of destiny and fate (crucially linked to the past) and the roman as a work that creates a narrative and existential present through the use of scenes. The récit relies on telling, while the roman subsumes telling within an overall strategy of showing. (Hence the common 20th Century command to aspiring writers of narrative: “Show, don’t tell!”) The difference between the two forms is, Jameson says, important “not as récit versus roman, nor even telling versus showing; but rather destiny versus the eternal present” (26). In Shame, Voice 1 is the voice of the récit (the [story]teller), Voice 2 is the voice of the roman, with the informational moments of telling subsumed within specific scenes, most dominantly the scene of writing. While the majority of the novel is written within a storytelling mode, the presence of Voice 2 infects that mode and inflects our reading, making Voice 1 into instances of what Voice 2 seeks to show.

Yet Voice 2’s will is a construction, and “what Voice 2 seeks” is itself an instance of “showing” within the text as a whole. The novel is the story of Voice 2 constructing and wrestling with Voice 1.

Jameson points out implications to his antinomies that may be useful as we return to Chaudhuri. In a discussion of the way that an aesthetic that constructs everyday existence as exterior/outside and an aesthetic that constructs existence as interior both avoid and resist genres that impose a prototypical destiny onto lived material, Jameson writes:

It is precisely against just such a reification of destinies that the realist narrative apparatus is aimed, which reaffirms the singularity of the episodes to the point at which they can no longer fit into the narrative convention. That this is also a clash of aesthetic ideologies is made clear by the way in which older conceptions of destiny or fate are challenged by newer appeals to that equally ideological yet historically quite distinct notion of this or that “reality,” in which social and historical material rise to the surface in the form of the singular or the contingent. (143)In Shame, the two aesthetic ideologies clash through the conflict between Voice 1 and Voice 2, and the synthesis they achieve is literally apocalyptic — the entire dialectic is blown away, making space for something new. The apocalypse synthesizes, perhaps, a new voice. Who is the blinded “I” in the final sentence (“…I can no longer see what is no longer there…” [305]), Voice 1 or Voice 2? We could choose to see them as merged, and thus the new possibilities of Voice 3 — or Voice ? — are born into the blank space.

The two ideologies clash in A Strange and Sublime Address, too, but not as obviously, because the text avoids any first-person narration. Nonetheless, its perspectives shift and there is a strong authorial voice guiding readers through the novel’s paths, a storyteller. We are given information by this voice, for instance: “There are several ways of spending a Sunday evening” (16). The storyteller also provides commentary: “He would become an archetype of that familiar figure who is not often described in literature — the ordinary breadwinner in his moment of unlikely glory, transformed into the centre of his universe and his home” (20). At times, the storyteller presents us with interpretations of what we are reading that are nearly as prescriptive as the interpretations offered by Voice 2 in Shame: “This kind of talk, whether at the dinner-table or in the bedroom, did not become too oppressive: it was too full of metaphors, paradoxes, wise jokes, and reminiscences to be so. It was, at bottom, a criticism of life” (48).

These examples of storytelling clash with the expectations created by the first paragraph of A Strange and Sublime Address and highlight this novel’s heteroglossia. Its polyphonies are not only at the level of narrative voice, but also of perspective, and it is through shifts in point of view that A Strange and Sublime Address makes its case for the location of reality within perception. From the first paragraph, we are set to expect the viewpoint character to be Sandeep, and certainly Sandeep is the primary viewpoint character, but the text moves away from his point of view with some regularity. Early in the novel, a mention of dust moves the narrative away from the room and out of Sandeep’s immediate perception to a simple declaration: “Calcutta is a city of dust,” which then leads to a portrayl of the servants who clean the dust from the rooms (14-15). Later, the text shifts a couple of times into Chhotomama’s point view, sometimes only for a few paragraphs (97), but once he is in the hospital, his point of view is the strongest and most defining (e.g., “But there were times, in the afternoon, when Chhotomama would wake from a nap and find himself facing a bright, hard wall. At first, it surprised him with its sheer presence. Slowly, he came to realise that it was his future he was looking at” (113).

Soon after highlighting Chhotomama’s perceptions, the text unifies the family’s perceptions as they drive away from visiting him: “Watching the lanes, they temporarily forgot their own lives, and, temporarily, their minds flowed outward into the images of the city, and became indistinguishable from them” (115).

Like Shame, A Strange and Sublime Address ends with a kind of obliteration, and one that is, in its implications, nearly as apocalyptic. Chhotomama sends Abhi and Sandeep out to the garden to look for a kokil, and his command is described as sounding “like a directive in a myth or a fable” (120). The search for the kokil puts the boys into the discourse of the pre-novel, the land of the fairy tale. They get distracted, though, and only find the kokil by mistake while playing hide-and-seek with each other. The bird is real, not a creature of myth. It has details that can be shown; it can become a character and not an archetype. The boys watch it eat an orange flower (the sort of apparently meaningless detail that creates, in Barthes’ sense, a reality effect). The first sentence of the final paragraph gives us a representation of perception tempered by probability and inductive reasoning: “But it must have sensed their presence, because it interrupted its strange meal and flew off”, which both provides us with an idea of perception and limits that perception, for it highlights that the kokil’s own perception cannot be known. The sentence is not finished, however. A dash slashes us into a revision: “—not flew off, really, but melted, disappeared, from the material world.” It’s as if the bird goes back into the mythic discourse of Chhotomama’s command. We, the readers, are left with the characters in the material world from which the bird has disappeared. What is that material world, though? It is the words of the book itself, because that is the world we share with the characters. The final sentence is mysterious: “As they watched, a delicate shyness seemed to envelop it, and draw a veil over their eyes” (121). The “it” of that sentence is nearly as mysterious as the “He” of the novel’s first sentence, and much more uncertain, because here we have no subsequent sentences to clarify it. The antecedent could be either the kokil or the material world. (Grammatically, it would be the latter, which is closer to the pronoun.) The kokil, having melted back to myth, cannot be the material world. But the ambiguous pronoun makes the force that veils the children’s eyes uncertain: is it myth or is it reality? Is it the absence of myth within reality?

The “I” of the last sentence of Shame could also have a few antecedents. The indeterminacy is meaningful because it makes us reflect on the importance of the antecedent as opposed to other elements of the sentences. Both novels offer an uncertain pronoun and a certain statement of blindness. “I can no longer see what is no longer there” could be a statement from one of the children in A Strange and Sublime Address. The voices of Shame are united in the indeterminant “I” of the end, as are the children of Chaudhuri’s novel. Both groups are blinded, and the blinding suggests that the mythic and historical past have been obliterated in favor not so much of a meaningful present as for the potential of a future. (In Chaudhuri, our group is, after all, a group of children, who, for all their claims of materiality, can’t help but stand for some sort of future.) Destiny is gone, fate is unknowable. The storyteller’s tale of the past became present voices and present details of the material world, but the present is temporary, as is perception, even when it flows out toward images of a city.

Speaking to Basu, Chaudhuri said Indian and postcolonial writers have been characterized as storytellers “emerging … from our oral traditions and our millennial fairy tales”, and the tone suggests he is skeptical or dismissive of this simplistic characterization, just as Basu is skeptical and dismissive of fairy tales beginning, “Once upon a time…” Both Shame and A Strange and Sublime Address conclude by obliterating fairy tales, myths, the past, and the present. The storyteller is a figure of the present because the story is the antecedent of the teller. The reader is more free, and may be, in fact, freed by the storyteller to shake off the nightmare of myth and the weight of history, to speculate on a future, to see a blankness, a potential, a voice marked by the question of infinity.

The paradox of once upon a time is that the storyteller’s recitation of the past may unleash the liberatory magic that we need. Once the present is named, it is past. Cities produce and receive perceptions and stories, but though their materiality may flow more slowly than perceptions and stories of that materiality do, even concrete and steel bend, weather, erode, melt, disappear. This is what the storyteller teaches, the knowledge that, in Benjamin’s terms, the righteous person keeps hidden until the story pries it loose, pulling away the veil, providing sight. Whether récit or roman, myth or material, the future always looms, a blank space like the blank page after the last sentence of a book.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Storyteller: Observations on the Works of Nikolai Leskov.” Trans. Harry Zohn. Selected Writings. Ed. Michael William Jennings and Howard Eiland. Vol. 3: 1935–1938. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1996. 143–166.

Chaudhuri, Amit. A Strange and Sublime Address. Freedom Song: Three Novels. New York: Vintage International, 2000. 1–121.

---. “Cosmopolitanism’s Alien Face.” New Left Review 55 (2009): 89–106.

Jameson, Fredric. The Antinomies of Realism. New York: Verso, 2013.

Majumdar, Saikat. “Dallying with Dailiness: Amit Chaudhuri’s Flaneur Fictions.” Studies in the Novel (2007): 448–464.

Rushdie, Salman. Shame. 1st Owl Book ed. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

0 Comments on Storytellers: Escaping the Nightmare of Myth in Chaudhuri and Rushdie as of 5/22/2014 8:36:00 AM

Add a Comment

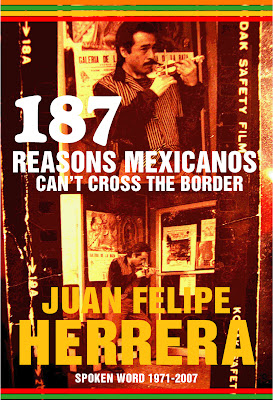

that's some good loving, herrera, enough to turn a bilingual educator into a code-switching loco, and more than enough to twang a chicano heart.

gracias, y sigue cantando.

RudyG

raúlrsalinas' work epitomizes both chicano and unitedstatesian art in so many ways. over at gemini there is a series of five videos featuring the aged poet reading his own stuff.

http://www.geminiink.org/salinas/

hey, lisa! glad to see you're gonna perform soon. while we're all morose over our fallen comrades, it's always great reminding gente, especially kids, that we, they, are the future. adelante!

"in liberation" indeed!

powerful - thanks so much - I'll share with my students next week - Lisa Alvarez