new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Woolf, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 12 of 12

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Woolf in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

It is far too early to tear down the barricades. Dancing shoes will not do. We still need our heavy boots and mine detectors.

—Jane Marcus, "Storming the Toolshed"

1. Seeking Refuge in Feminist Revolutions in ModernismLast week, I spent two days at the

Modernist Studies Association conference in Boston. I hadn't really been sure that I was going to go. I hemmed and hawed. I'd missed the call for papers, so hadn't even had a chance to possibly get on a panel or into a seminar. Conferences bring out about 742 different social anxieties that make their home in my backbrain. I would only know one or maybe two people there. Should I really spend the money on conference fees for a conference I was highly ambivalent about? I hemmed. I hawed.

In the end, though, I went, mostly because my advisor would be part of a seminar session honoring the late

Jane Marcus, who had been her advisor. (I think of Marcus now as my grandadvisor, for multiple reasons, as will become clear soon.) The session was titled "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers: Feminist Revolutions in Modernism", the title being an homage to Marcus's essay "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers" from the 1981 anthology

New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf, itself an homage to the phrase in Woolf's

A Room of One's Own. Various former students and colleagues of Marcus would circulate papers among themselves, then discuss them together at the seminar. Because of the mechanics of seminars, participants need to sign up fairly early, and I'd only registered for the conference itself a few days before it began, so there wasn't even any guarantee I'd been able to observe; outside participation is at the discretion of the seminar leader. Thankfully, the seminar leader allowed three of us to join as observers. (I'm trying not to use any names here, simply because of the nature of a seminar. I haven't asked anybody if I can talk about them, and seminars are not public, though the participants are listed in the conference program.)

Marcus was a socialist feminist who was very concerned with bringing people to the table, whether metaphorical or literal, and so of course nobody in the seminar would put up with the auditors being out on the margins, and they insisted that we sit at the table and introduce ourselves. Without knowing it, I sat next to a senior scholar in the field whose work has been central to my own. I'd never seen a picture of her, and to my eyes she looked young enough to be a grad student (the older I get, the younger everybody else gets!). When she introduced herself, I became little more than a fanboy for a moment, and it took all the self-control I could muster not to blurt out some ridiculousness like, "I just love you!" Thankfully, the seminar got started and then there was too much to think about for my inner fanboy to unleash himself. (I did tell her afterwards how useful her work had been to me, because that just seemed polite. Even senior scholars spent a lot of hours working in solitude and obscurity, wondering if their often esoteric efforts will ever be of any use to anybody. I wanted her to knows that hers had.) It soon became the single best event I've ever attended at an academic conference.

|

| Jane Marcus |

To explain why, and to get to the bigger questions I want to address here, I have to take a bit of a tangent to talk briefly about a couple of other events.

The day before the Marcus seminar, I'd attended a terrible panel. The papers that were about things I knew about seemed shallow to me, and the papers not about things I knew about seemed like pointless wankery. I seriously thought about just going home. "These are not my people," I thought. "I do not want to be in their academic world."

I also attended a "keynote roundtable" session where three scholars — Heather K. Love, Janet Lyon, and Tavia Nyong’o — discussed the theme of the conference: modernism and revolution. Sort of. It was an odd event, where Love and Nyong'o were in conversation with each other and Janet Lyon was a bit marginalized, simply because her concerns were somewhat different from Love and Nyong'o's and she hadn't been part of what is apparently a longstanding discussion between them. I mention this not as criticism, really, because though the side-lining of Lyon felt weird and sometimes awkward, the discussion was nonetheless interesting and vexing in a productive way. (I know Love and Nyong'o's work, and appreciate it a lot.) I especially appreciated their ideas about academia as, ideally, a refuge for some types of people who lack a space in other institutions and have been marginalized by ruling powers, even if there are no real solutions, given how deeply infused with ideas of finance and "usefulness" the contemporary university is, how exploitative are the practices of even small schools. (Nyong'o works at NYU, an institution that has become

the mascot for neoliberalism. His recent blog essay

"The Student Demand" is important reading, and was referenced a number of times during the roundtable.) As schools make more and more destructive decisions at the level of administration and without the faculty having much obvious ability to challenge them, the position of the tenure-tracked, salaried faculty member of conscience is difficult, for all sorts of reasons I won't go into here. As Nyong'o and Love pointed out, the moral position must often be that of a criminal in your own institution.

All of this was on my mind the next day as I listened to discussions of Jane Marcus. After the seminar, some of us went out to lunch together and the discussion continued. What I kept thinking about was the idea of refuge, and the way that certain traditions of teaching and writing have opened up spaces of refuge within spaces of hostility. Marcus stands as an exemplar here, both in her writing and her pedagogy. The question everyone kept coming back to was: How do we continue that work?

In her 1982 essay "Storming the Toolshed", Marcus reflected on the position of various feminist critics ("lupines" — she appropriated Quentin Bell's dismissive term for feminist Woolfians, reminding us that it is also a name for a

flower):

Feminists often feel forced by economic realities to choose other methodologies and structures that will ensure sympathetic readings from university presses.We may be as middle class as Virginia Woolf, but few of us have the economic security her aunt Caroline Emelia Stephen's legacy gave her. The samizdat circulation among networks of feminist critics works only in a system where repression is equal. If all the members are unemployed or underemployed, unpublished or unrecognized, sisterhood flourishes, and sharing is a source of strength. When we all compete for one job or when one lupine grows bigger and bluer than her sisters with unnatural fertilizers from the establishment, the ranks thin out. Times are hard and getting harder.

Listening to her students and colleagues remember her, I was struck by how well Marcus had tended her own garden, how well she had tried to keep it from being fatally poisoned by the unnatural fertilizers of the institutions of which she was a part. She found opportunities for her students to research and publish in all sorts of places, she supported scholars she admired, and when she couldn't find opportunities for other people's work, she did was she could to create them. She was tenacious, dogged, sometimes even insufferable. This clearly did not always lead to the easiest of relationships, even with some of her best friends and favorite students. As with so many brilliant people, her virtues were intimately linked to her faults. Jane Marcus without her faults would not have been Jane Marcus. Faults and all ("I've never been so mad at somebody!"; "We didn't speak to each other for a year"), again and again people said: "Jane gave me my life."

There seemed to be a sense among the seminar participants that the sort of politically-committed, class-conscious feminism that Marcus so proudly stood for is on the wane in academia, and that while the field of modernist studies may be more open to marginalized writers than it was 30 or 40 years ago, the teaching of modernism in university classes remains very male, very Eliot-Pound-Joyce, with a bit of Woolf thrown in as appeasement to the hysterics. (I have no idea whether this is generally accurate, as I have not done any study of what's getting taught in classes that cover modernist stuffs, but it was the specific experience of a number of people at the conference.) Since the late '90s, there's been the historically-minded New Modernist Studies*, but the question keeps coming up: Does the New Modernist Studies do away with gender ... and if so, is the New Modernist Studies a throwback to the pre-feminist days? Anne Fernald looked at the state of things in the introduction to the

2013 issue of Modern Fiction Studies that she edited, an issue devoted to women writers:

The historical turn has revitalized modernist studies. Beginning in the late 1990s, its impact continues in new book series from Oxford and Columbia University Presses; in the Modernist Studies Association (MSA), whose annual conference has attracted hundreds of scholars; and in burgeoning digital archives such as the Modernist Journals Project. Nonetheless, one hallmark of the new modernist studies has been its lack of serious interest in women writers. Mfs has consistently published feminist work on and by women writers, including special issues on Spark, Bowen, Woolf, and Stein; still, this is the journal’s first issue on feminism as such in nineteen years. Modernism/modernity, the flagship journal of the new modernism and the MSA, has not, in nineteen years, devoted a special issue to a women writer or to feminist theory. Only eight essays in that journal have “feminist” or “feminism” as a key term, while an additional twenty-six have “women” as a key term. And, although The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms includes many women contributors, only one of the twenty-eight chapters mentions women in its title, and, of the six authors mentioned by name, only one—Jean Rhys—is a woman.

Similarly, Marcus's socialism and Marxism may not be especially welcome among the New Modernists, for as Max Brzezinski polemically suggests in

"The New Modernist Studies: What's Left of Political Formalism?", the

New in

New Modernist Studies could easily slip into the

neo in

neo-liberal.

For scholars who have at least some sympathy with Marcus's political stance, there's a lot of deja vu, even weariness. How long, they wonder, must the same battles be fought?

For once, I'm not as pessimistic as other people. Routledge is launching a new journal of feminist modernism (with Anne Fernald as co-editor). Within the world of Virginia Woolf studies, much attention is being paid to Woolf's connections to anti-colonialism and to her ever-more-interesting writings in the last decade of her life. There is a strong transnational and postcolonial tendency among many scholars of modernism of exactly the sort that Marcus herself called for and exemplified, particularly in her later writings. Vigilance is necessary, but vigilance is always necessary. Networks of scholars and traditions of inquiry that Marcus participated in, contributed to, and in some cases founded remain strong.

As some of the people at the conference lamented the steps backward to regressive, patriarchal views, I thought of how lucky I've been in how I've learned to read and perceive this undefinable thing we call "modernism". The modernisms I perceive are ones where women are central. The Joyce-Pound-Eliot modernism is one I'm familiar with, but not one I think of first.

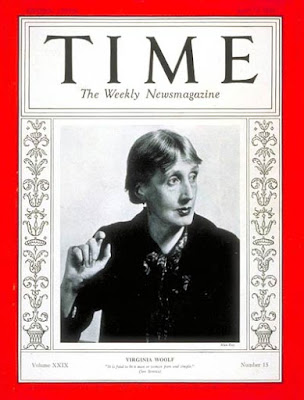

2. ForemothersI discovered Woolf right around the time I discovered Joyce and Kafka. I was too young (12 or 13) to understand any of their work in any meaningful way, but something about them fascinated me. I flipped through their books, which I found at the local college library. I read Kafka's shortest stories. I memorized the first few lines of

Finnegans Wake, though never managed to get more than a few pages into the book itself. I read

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, enjoying the first chapter very much and not getting a lot from the later ones (I still don't, honestly. My tastes aren't Catholic enough). I skimmed the last section of

Ulysses, looking to see how Joyce made Molly Bloom's stream of consciousness work. And then I read the first few pages of

Mrs. Dalloway. That wasn't a library book, but a book I bought with my scant bits of allowance money, saved up for probably a month. It was a mass market paperback with a bright yellow cover. I read the first 50 or so pages of the book and found it enthralling and perplexing. It ended up being too much for me. But there was something there. The first paragraphs were among the most beautiful things I'd ever read.

Skip ahead five or six years and I'm a student at NYU, studying Dramatic Writing. A friend I respect exhorts me to take a course with Ilse Dusoir Lind, who has mostly retired but comes back now and then to teach a seminar, this term on Faulkner and Hemingway. She wrote some of the earliest critical articles on Faulkner and, she later tells me, helped found the Women's Studies program at NYU. My friend was right: her class is remarkable. I don't much like Hemingway except for some of his short stories, but she takes us through

The Sun Also Rises, various stories, and

The Garden of Eden with panache. (I particularly remember how ridiculous and yet captivating she thought

The Garden of Eden was.) And then of course Faulkner, her great love. She taught us to read

The Sound and the Fury and

Absalom, Absalom!, for which I will always be grateful. Thus, my first experience of academic modernism was an experience of two of the most major of major modernist men seen through the eyes of a brilliant woman.

Skip ahead a year or so later and I've just finished my junior year of college. I've decided to transfer from NYU to UNH for various reasons. It's a tough summer for me, a summer of reckoning with myself and my world. I work at the

Plymouth State College bookstore, a place I've worked on and off for a number of summers since middle school. That June, the College is hosting the

International Virginia Woolf Society's annual conference, organized by a relatively new member of the PSC English Department,

Jeanne Dubino. My colleagues at the bookstore are all working as volunteers at the conference. They introduce me to Jeanne and I join the ranks of the volunteers. The bookstore goes all-out with displays. We stock pretty much every book by and about Woolf in print in the US. I remember opening the boxes and helping to shelve the books. None of us were efficient at shelving because we couldn't stop looking at the books.

Hermione Lee's

biography had just come out and we hung a giant poster of it up. I bought a copy (35% employee discount!) and began to devour it. One night, I was working the registration desk. Hermione Lee came in. She was giving the keynote address. She was late, having been delayed by weather or something. She was tired, but friendy. "Can I still get my registration materials?" she asked. "Certainly," I said. "And might I ask you to sign my book in return?" She laughed, said of course, and did so while I finished with her paperwork.

I found the conference enthralling. I never wanted to go home. (My parents had just divorced; being at the conference was much more fun than being at the house with my father.) The passion of the participants was contagious. Jeanne was astoundingly composed and friendly for someone in charge of a whole academic conference, and we continued to talk about Woolf now and then until she left Plymouth for other climes. I got to know Woolf because I got to know Jeanne.

Skip forward 6 months to the spring term of my senior year at UNH. By some bit of luck and magic, the English Department offered an upper-level seminar on Woolf this term and I was able to fit it into my schedule. I was the only male in the class, and relatively early on one of the other students said to me, in a tone of voice reserved for a rare and yet quite unappealing insect, "Why are you here?" (What did I reply? I don't remember. I probably said because I like Woolf. Or maybe: Why not?) The instructor was Jean Kennard. We read all of the novels except

Night and Day, plus we read

A Room of One's Own,

Three Guineas, and numerous essays. It was one of the hardest courses I've ever taken, either undergrad or grad, and one of the best. It exhausted me to the bone, and yet I wouldn't have wanted it to do anything less. Few courses have ever stayed with me so well or let me draw on what I learned in them for so long. Prof. Kennard was exacting, interesting, and intimidatingly knowledgeable. I didn't dare read with anything less than close attention and care, even if that meant not sleeping much during the term, because I feared she would ask me a question in class and I would be unprepared and give a terrible answer, and there was no way I was going to allow myself to do that because I already identified as someone for whom Virginia Woolf's work was important. I figured either I'd do well in the class or I'd collapse and be put on medical leave. (I had other classes, of course, and I was acting in some plays, and there was a bit of work on the side to give me some income, so not many free hours for sleeping.)

In the days of the

LitBlog Co-op in the early 2000s, I met

Anne Fernald. I didn't know she was a Woolfian or involved in modernist studies; I knew her as a blogger. Eventually, we talked about Woolf. (When I moved to New Jersey in the summer of 2007, Anne gave me a tour of the area. I remember asking her how

work on a critical edition of

Mrs. Dalloway was coming, naively expecting that work must be almost done. We had to wait a few more years. It was worth the wait.)

I didn't really encounter modernism in a classroom again until recently, because it wasn't a part of my master's degree work, except peripherally in that to study Samuel Delany's influences, which I did for the master's thesis, meant to study a lot of modernism, though modernism through his eyes. But his eyes are those of a black, queer man influenced by many women and committed to feminism, so once again my view of modernism was not that of the patriarchal white order, even though plenty of white guys were important to it.

And then PhD classes and research, where once again women were central. (It was in one such class that I first read Jane Marcus's

Hearts of Darkness: White Women Write Race.)

Thus, this quick overview of my own journey is a story of women and modernism. My own learning is very much the product of the sorts of efforts that Marcus and other feminist modernists made possible, the work they devoted their lives to. They are my foremothers, and the foremothers of so many other people as well. My experience may be unique in its weird bouncing across geographies and decades and media (I've never been very good at planning my life), but I hope it is not uncommon.

3. Reading MarcusI've been reading lots of Jane Marcus for the last month or so. Previously, I'd only read

Hearts of Darkness and a couple of the most famous earlier essays. Now, though, I've been combing through books and databases in search of her work. (At the MSA seminar, someone who had had to submit Marcus's CV for a grant application said it was 45 pages long. She published hundreds of essays and review-essays in addition to her books.)

I'm tempted to drop lots of quotes here — Marcus is eminently quotable. But perhaps a better use of this space would be to think about Marcus's own style of writing and thinking, the way she formed and organized her essays, which, much like Woolf's many essays, show a process of thought in development.

At the end of the first chapter of

Hearts of Darkness, which collects some of her more recent work, Marcus writes:

The effort of these essays is toward an understanding of what marks the text in its context, to hear the humming noise whose rhythm alerts us to the time and place that produced it, as well as the edgy avant-garde tones of its projection into the modernist future. For modernism has had much more of a future than one could have imagined. In a new century the questions still before me concern the responsibility for writing those once vilified texts into classic status in a new social imaginary. If it was once the critic's role to argue the case for canonizing such works, perhaps it is now her role to question their status and explore their limits.

This statement concisely maps the direction of Marcus's thinking over the course of her career. Her efforts were first to recover texts that had fallen out of the sight of even the most serious of readers, then to advocate for those texts' merits, then to convince her students and colleagues to add those texts to curricula and, in many cases, to help bring them back into print. She argued, for instance, for a particular version of Virginia Woolf, one at odds with a common presentation of Woolf as fragile and apolitical and sensitive and tragic. Marcus was having none of that. Woolf was a remarkably strong woman, a nuanced political thinker whose ideas developed significantly over time and came to a kind of fruition in the 1930s, and a far more complex artist than she was said to be. Later, though, Marcus didn't need Woolf to be quite so much of a hero. She was still all the things she had been before, but she was also flawed, particularly when it came to race. The Woolf that Marcus looks at in

"'A Very Fine Negress'" and

"Britannia Rules The Waves" is in many ways an even more interesting Woolf than in Marcus's earlier writings, because she is still a Woolf of immense depth but also immense contradictions and blind spots and very human failures of perception and sympathy. Marcus's earlier Woolf is Wonder Woman (though one too often mistaken for a mousy, oversensitive, snobby, mentally ill

Diana Prince), but her later Woolf is more like a brilliant, frustrating friend; someone striving to overcome all sorts of circumstances, someone capable of the most beautiful creations and insights, and yet also sometimes crushingly disappointing, sometimes even embarrassing. A human Woolf from whom we can learn so much about our own human failings. After all, if someone as remarkable as Woolf could be so flawed in some of her perceptions, what about us? In exploring the limits and questioning the status of the works we once needed to argue into the mainstream conversation, we also remind ourselves of our own limits, and perhaps we develop better tools with which to question our own status in whatever places, times, and circumstances we happen to inhabit.

This is not to say that Marcus's early work is irrelevant. Not at all. It is still quite thrilling to read, and rich with necessary insights. (If anything, it does make me sad that a number of her best, most cutting insights about academia and power relations remain fresh today. There's been progress, yes, but not nearly enough, and much that was bad in the past repeats and repeats into our future.) Here's an example, from

a May 1987 review in the Women's Review of Books of

E. Sylvia Pankhurst: Portrait of a Radical by Patricia Romero, a book Marcus thought misrepresented and misinterpreted its subject. Near the end, after detailing all the ways Romero fails Pankhurst, Marcus makes a sharp joke:

Sylvia Pankhurst has had her come-uppance so many times in this book that there's hardly anywhere for her to come down to. Romero says that she met her husband on the same day that she met Sylvia Pankhurst's statue in Ethiopia. One hopes that he fared better than Sylvia.

Ouch. But this joke serves as a conclusion to the litany of Romero's failures as Marcus saw them and turns then to a larger point:

Let it be clear that I am not calling for nurturant biographies of feminist heroines. I, too, as a student of suffrage, have several bones to pick with Sylvia Pankhurst. In writing The Suffragette Movement she not only distorted history to aggrandize the role of working-class suffragettes in winning the vote, but, more importantly, she wrote the script of the suffrage struggle as a family romance, a public Cinderella story with her mother and sister cast as the Wicked Stepmother and Stepsister. It was this script which provided George Dangerfield and almost every subsequent historian of suffrage with the materials for reading the movement as a comedy. Sylvia provided them with a false class analysis which persists. Patricia Romero now unwittingly wears the mantle woven by Sylvia Pankhurst as the historian so bent on the ruthless exposure of her subject that she gives the enemies of women another hysteric to batter — though the prim biographer would doubtless be horrified at the suggestion that the Sylvia Pankhurst whom she despises and exposes was engaged in a project similar to her own and is, in fact, her predecessor.

Such an amazingly rich paragraph! The review up to now has been Marcus showing the ways that she thinks Romero misrepresents Sylvia Pankhurst, and the effect is mostly to make us think Marcus venerates Pankhurst totally and is defending the honor of a hero against a detractor. But no. Her message is that feminist history deserves better: it deserves accuracy.

Both Romero and Pankhurst failed this imperative by letting their ideologies and prejudices hide and mangle nuances. Both Romero and Pankhurst, wittingly or unwittingly, presented the deadly serious history of the suffrage movement as comedy. Both, wittingly or unwittingly, provided cover and even ammunition for misogynistic discourse. And that, ultimately, is the argument of Marcus's review. She sees her job as a reviewer not to be someone who gives thumbs up or thumbs down, but to be someone who can analyze what sort of conversation the book under review enters into and supports. The limitations she sees in the book are not just the limitations of one book, but limitations endemic to an entire way of presenting history.

She then brings the review back to Pankhurst and Romero's portrait of her, and now we as readers can appreciate a larger vantage to the evaluation, because we know it's not just about this book, but about historiography and feminism. Marcus mentions some other, better books (a hallmark of her reviews: she never leaves the reader wondering what else there is to read — in negative reviews such as this one, it's books that do a better job; in positive reviews, it's other books that contribute valuable knowledge to the conversation), then:

The problem with the historian's project of setting the record straight is that it flourishes best with a crooked record, the crookeder the better. Romero has found in Sylvia Pankhurst's life the perfect crooked record to suit her own iconoclastic urge.

We might think that Marcus here is holding herself apart from "the historian's project of setting the record straight", that she is setting herself up as somehow perfect in her own sensibilities. But in the next sentence she shows that is not the case:

Admitting one's own complicity as a feminist in all such iconoclastic activity, one is still disappointed in the results. I came to this book anticipating with a certain relish the pleasure of seeing Sylvia Pankhurst put in her place. But because the author writes with such contempt for her subject as well as for activism of all kinds, I came away with a deep respect for Sylvia Pankhurst and the work she did for social justice.

To be a feminist is to be iconoclastic. To be a feminist is to be faced with many crooked records. But this book can serve, Marcus seems to be saying, a warning of what can happen when the desire to be an iconoclast overcomes the desire to be accurate, and when one is tempted to add some crooks to the record before straightening it out. The danger is clearly implied: Beware that you do not depart too far from accuracy, lest you lead your reader to the opposite of the conclusions you want to impart.

Marcus would have been a wonderful blogger. Her writing style is discursive, filled with offhand references that would make for marvelous hyperlinks, and she doesn't waste a lot of time on transitions between ideas. At the MSA seminar, someone said that Marcus's process was to write lots of fragments and then edit them together when she needed a paper. Her writing is a kind of assemblage, both in the sense of

Duchamp et al. and of

Deleuze & Guattari.

(In the course where we read

Hearts of Darkness, one of the other students pointed out that Marcus jumps all over the place and rarely seems to have a clear thesis — her ideas are accumulative, sometimes tangential, a series of insights working together toward an intellectual symphony. If we were to write like that, this student said, wouldn't we just get criticized for lack of focus, wouldn't our work be rejected by all the academic publishers we so desperately need to please if we are to have any hope of getting jobs or tenure? "She can write like that," our instructor said, "because she's Jane Marcus." Which in many ways is true. We read Jane Marcus to follow the lines of thought that Jane Marcus writes. It's hard to start out writing like that, but once you have a reputation, once your work is read because of your byline and not just because of your subject matter, you have more freedom of form. And yet I also think we should be working toward a world that allows and perhaps even encourages such writing, regardless of fame. Too many academic essays I read are distorted by the obsession with having a central claim; they sacrifice insight for repetitious metalanguage and constant drumbeating of The Major Point. It's no fun to read and it makes the writing feel like a tedious explication of the essay's own abstract. Marcus's writing has the verve, energy, and surprise of good essayistic writing. This was quite deliberate on her part — see her comments in

"Still Practice, A/Wrested Alphabet: Toward a Feminist Aesthetic" on Woolf as an essayist versus so many contemporary theorists. I don't entirely agree with her argument, since I don't think "difficult" writing should only be the province of "creative writers" and not critics, but I'd also much prefer that writers who are not geniuses aspire to write more like Woolf in her essays than like Derrida. And the insistence that academic writers build Swamp Thing jargonmonsters to prove their bona fides is ridiculous.)

Her discursive, sometimes rambling style serves Marcus well because it allows her to connect ideas that might otherwise get left by the wayside. Marcus makes the essay form do what it is best at doing. Her 1997 essay

"Working Lips, Breaking Hearts: Class Acts in American Feminism" masterfully demonstrates this. At its most basic level, the essay is a review (or, as Marcus says, "a reading") of

Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism, which builds off of the work of Tillie Olsen, particularly her invaluable book

Silences. But Marcus's essay is far more than just a look at this one anthology — it is also a tribute to

Tillie Olsen, who herself influenced Marcus tremendously, a study of feminist-socialist theory and history, a manifesto about canons and canonicity, a personal memoir, and even, in one moving footnote, an obituary for Constance Coiner, a feminist scholar who died in the crash of

TWA flight 800.

By writing about Olsen, a generation her elder, Marcus is able to take a long view of American feminism, its past and future. She's writing just as the feminists of the 1970s are becoming elders themselves and a new generation of feminists is moving the cause into new directions, often without sufficient attention to history. Discussing one of the essays in

Listening to Silences, she writes:

More troublesome (or perhaps merely more difficult for me to see because of my own positionality) is Carla Kaplan's claim that my generation of American feminist critics used a reading model "based on identification of reader and heroine, and it tended to ignore class and race differences among women" (10). She assumes that the generation influenced by Olsen always produced such limited readings of exemplary texts — Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper", Susan Glaspell's "A Jury of Her Peers", and Isak Dinesen's "The Blank Page" — without acknowledging that there was a strong and vocal objection to reading these texts historically as merely embodying the interests of certain feminist critics themselves. I know I was not alone in choosing never to teach them. (I have often said that these texts were chosen because they reflected the experience of feminists in the academy.) In addition, it seems important to make clear that the differences among women made by race, class, and sexual orientation were marked by many critics at the time (always by Gayatri Spivak and Lillian Robinson, e.g., and often by other nonmainstream feminist critics). There is a real danger in essentializing the work of a whole generation of feminists.

What Marcus repeatedly did for the history of British modernism, especially in the 1930s, she here does for the history of the movement she herself was part of: She calls for us not to reduce the history to a single tendency, not to make the participants into clones and drones. She acknowledges that some feminists in the 1970s and 1980s read from a place of self-identification, oblivious to race and class, but exhorts us to remember that not everyone did, and that in fact there was discussion among feminists not only about race and class, but about how to read as a feminist. She doesn't want to see her own generation and movement reduced to stereotypes in the way the British writers of the 1930s especially were. Throughout

Hearts of Darkness, she writes about

Nancy Cunard, first to overcome the many slanders of Cunard over the decades, but also to offer a useful contrast with Woolf in terms of racial perceptions and desires. She wants attention to

Claude McKay and

Mulk Raj Anand because only reading white and mostly male writers distorts history, which distorts our perception of ourselves: "It is my opinion that the study of the period would be greatly enriched by wresting it from the hands of those who leave out the women and the people of color who were active in the struggle for social change in Britain. It is important for students to know that leftists in the thirties were not all leviathans on the questions of race, gender, and class. Not all their hearts were dark. ...the critics before us deliberately left us in the dark about the presence of black and South Asian intellectuals on the cultural scene" (181). (Peter Kalliney's recent

Commonwealth of Letters does some of the work of tracing these networks, and

Anna Snaith has done exemplary work in and around all of this.)

"Working Lips, Breaking Hearts" brings all of these interests together, and does so not only for British and U.S. writers and activists of the 1930s, but also for Marcus's own generation of feminists.

This is our history, she seems to say,

and we must take care of it, or else what was done to the people of the 1930s by historians and literary critics will be done to us.

In

"Suptionpremises", a blistering 2002 review-essay about critics' interpretations of whites' uses of black culture in the 1920s and 1930s, Marcus wrote:

Why should cross-racial identification with the oppressed be perceived as evil? Certainly, while it was both romantic and revolutionary and very much of the period, such love for the Other is not in itself a social evil. The embrace of the Other and the Other’s values and the Other’s arts, language, and music, has often been progressive. Interracial sex and interracial politics were and are important to any radical cultural agenda. Cunard and [Carl] Van Vechten were not sleeping with the enemy. One might even say that the bed, the barricade, the studio, and the boîte, or Paris nightclub, were the sites where the barriers to progressive human behavior were broken down.

But the mistaking of those whites who loved blacks, however motivated by desire, politics, or by sheer pleasure at hearing the music and seeing the extraordinary art of another people, as merely a set of cultural thieves does not contribute to our understanding of the cultural forces at work here.

The cultural forces at work were ones Marcus begins to see as queer:

The fear that motivates [critics] North, Douglas, and Gubar is the taint of the sexually perverse. What is the fear that motivates Archer-Straw and Bernard? Is it fear of the damage done to the stability of the black family and the wholeness of black art by the attention of queer white men and white women who broke the sexual race barrier? If we try to look at this from outside the separatist anxieties that are awakened on both sides of the color line by these early personal and political crossings, the modernist figures represent a rare coming together of radical politics, African and African American art and culture, and white internationalist avant-garde and Surrealist intellectuals. These encounters deserve attention as a queer moment in cultural history and I think that is the only way to get beyond the impasse of discomfort about the modernist race pioneers in our current critical thinking. If it is because of a certain liberated queer sexuality that certain figures could cross the color line, could try to speak black slang, however silly it sounded, then sex will have to take its place as a major component in the translation of ideas.

As she so often did, Marcus pays attention here to what she thinks are the forces and desires that construct certain interpretations. "Why this?" she asks again and again, "and why now?" What sort of work do these kinds of interpretations do, whom do they help and whom do they hurt, what do they make visible and what do they leave invisible? What social or personal need do they seem to serve? And then the implied question: Whom do my own interpretations help or hurt? What do I make visible or invisible by offering such an interpretation?

One of Marcus's masterpieces was not a book she wrote herself, but

an annotated edition of Woolf's Three Guineas that she edited for Harcourt, published in 2006.

Three Guineas had not been served well by most critics and editors over the years, and Marcus's edition was the first American edition to include the photographs Woolf originally included, but which, for reasons no-one I know of has been able to figure out, were dropped from all printings of the book after Woolf's death. Marcus provided a 35-page introduction, excerpts from Woolf's scrapbooks, annotations that sometimes become mini-essays of their own, and an annotated bibliography. It's a model of a scholarly edition aimed at common readers (as opposed to a scholarly edition aimed at scholars, which is a different [and also necessary] beast, e.g. the

Shakespeare Head editions and the

Cambridge editions of Woolf). (She had already laid out her principles for such Woolf editions in a jaunty, often funny, utterly overstuffed, and quite generous

review of [primarily] Oxford and Penguin editions in 1994, and it seems to me that we can feel her chomping at the bit to do one of her own.)

Three Guineas is in many ways the key text for Marcus, a book overlooked and scorned, even hated, but which she finds immense meaning in. Her annotated edition allows her to show exactly what meanings within the text so deeply affected her. It's a great gift, this edition, because it not only gives us a very good edition of an important book, but it lets us read along with Jane Marcus.

It's unfortunate that Marcus never got to realize her dream of a complete and unbowdlerized edition of Cunard's

Negro anthology. Copyright law probably makes re-issuing the book an impossible task for at least another generation, given how many writers and artists it includes, although perhaps a publisher in a country with less absurd copyright regulations than the US could do it. (Aside: This is yet another example of how long copyright extensions destroy cultural knowledge.) Even the highly edited

version from 1970 is now out of print, though given how Marcus blamed that edition for many misinterpretations of Cunard and her work, I doubt she'd be mourning its loss. I wish somebody could create a digital edition, at least. Even an illegal digital edition. Indeed, that would perhaps be most in the spirit of the original text and of Marcus — somebody should get hold of a copy of the first edition, scan it, and upload it to

Pirate Bay. We need to be criminals in our institutions, after all...

4. Refuge and the CriminalLet us go then, you and I, back to where we began: refuge and revolutions.

"the numbers show that the teaching staff at America's universities are much whiter and much more male than the general population, with Hispanics and African Americans especially underrepresented. At some schools, like Harvard, Stanford, the University of Michigan, and Princeton, there are more foreign teachers than Hispanic and black teachers combined. The Ivy League's gender stats are particularly damning; men make up 68 percent and 70 percent of the teaching staff at Harvard and Princeton, respectively."

—Mother Jones, 23 November 2015

(Somewhere, Jane Marcus says that we may have to work and live in institutions, but that doesn't mean we have to

like them.)

"Experts think that the more than $1.3 trillion in outstanding education debt in the U.S. is more than that of the rest of the world combined."

—Bloomberg, 13 October 2015

My own assemblage here breaks down, because I have no conclusions, only impressions and questions.

Right now we are in the midst of a humanitarian crisis,

a refugee crisis. In my own state of New Hampshire, the Democratic governor, Maggie Hassan,

said there should be a halt to accepting all refugees from Syria. It is an ignorant and immoral statement. Maggie Hassan is a typical centrist Democrat, always rushing to put disempowered people in the middle of the road to get run over by the monster trucks of the ruling class.

"Since Sept. 11, 2001, nearly twice as many people have been killed by white supremacists, antigovernment fanatics and other non-Muslim extremists than by radical Muslims: 48 have been killed by extremists who are not Muslim, including the recent mass killing in Charleston, S.C., compared with 26 by self-proclaimed jihadists, according to a count by New America, a Washington research center."

—NYT, 24 June 2015

Yesterday (as I write this),

a man walked into a Planned Parenthood clinic with a gun. He killed three people before police were able to take him into custody. It was an act of terrorism, but will seldom be labelled that. Maggie Hassan will not call for middle-aged white men with beards to be barred from entry.

"The Republicans also organized a gun-buyer’s club, meeting in a conference room during work hours to design custom-made, monogrammed, silver-plated 'Tiffany-style' Glock 9 mm semi-automatic pistols."

—Slate, 24 November 2015

As I write this,

U.S. police officers have killed 1,033 people this year, including 204 unarmed people. The shooter at the Planned Parenthood clinic is very lucky to be alive. This proves it is actually possible for U.S. police not to kill people they intend to take into custody, even when they're armed. If the shooter had been a black man, though, I expect he would be dead right now.

"'We are locked and loaded,' he says, holding up a black 1911-style pistol. As he flashes the gun, he explains amid racial slurs that the men are headed to the Black Lives Matter protest outside Minneapolis’ Fourth Precinct police headquarters. Their mission, he says, is 'a little reverse cultural enriching.'"

—Minneapolis Star Tribune, 25 November 2015

Laquan McDonald had a small folding knife and was running away.

16 bullets took him down.

(Have you seen

M.I.A.'s new video, "Borders"? You should.)

(What can we use, too, from

Wendy Brown's recent discussion of rifts over gender and womanhood? What is getting lost, and what is newly seen?)

"The year-to-date temperature across global land and ocean surfaces was 1.55°F (0.86°C) above the 20th century average. This was the highest for January–October in the 1880–2015 record, surpassing the previous record set in 2014 by 0.22°F (0.12°C). Eight of the first ten months in 2015 have been record warm for their respective months."

—National Centers for Environmental Information

(I could go on and on and on. I won't, for all our sakes.)

After listening to Heather Love and Tavia Nyong'o at MSA, I came back to the idea I've been tossing around, inspired by Steve Shaviro's great book

No Speed Limit, of the value of aesthetics to at least stand outside neoliberalism. Love and Nyong'o seemed dismissive of aesthetics, and I wanted to mention

Commonwealth of Letters to them, and propose that perhaps if an art-for-art's-sake aesthetic is not, obviously, an instigator of utopian revolution, it may be a refuge. Kalliney shows that such an attention to aesthetics was just that for some colonial subjects in the 1930s who came to London to be writers and intellectuals. I am wary of an anti-aesthetic politics, a politics that seeks revolution but not the good life, a politics that does the work of neoliberalism by insisting on usefulness.

The university certainly has been an imperfect refuge, often just the opposite of refuge. Aesthetic attention will not open up a panacea or a utopia, nor will the refuge it provides be significantly more just and effective than the refuge of academia. But it is not nothing, and it is not anti-political. I think Marcus's writings demonstrate that. She recuperates

The Years and

Three Guineas not only by arguing for their political power, but for their aesthetic achievements. They survive, and we who cherish them are able to cherish them, not only because of what they say, but how they say it. Form matters. Form is matter.

Which is not to say, of course, that we should descend into a shallow formalism any more than we should wrap ourselves in the righteousness of an easy economism. Remember history. Remember nuance. Remember not to distort realities for the sake of an easy point. Don't provide cover for the exploiters and oppressors.

5. Art and Anger

Photographs of suffragettes lying bloody, hair dishevelled, hats askew, roused public anger toward the women, not their assailants. They were unladylike; they provoked the authorities. Demonstrations by students and blacks arouse similar responses. Thejustice of a cause is enhanced by the nonviolence of its adherents. But the response of the powerful when pressed for action has been such that only anger and violence have won change in the law or government policy. Similar contradictions and a double standard have characterized attitudes toward anger itself. While for the people, anger has been denounced as one of the seven deadly sins, divines and churchmen have always defended it as a necessary attribute of the leader. "Anger is one of the sinews of the soul" wrote Thomas Fuller, "he that wants it hath a maimed mind." "Anger has its proper use" declared Cardinal Manning, "Anger is the executive power of justice." Anger signifies strength in the strong, weakness in the weak. An angry mother is out of control; an angry father is exercising his authority. Our culture's ambivalence about anger reflects its defense of the status quo; the terrible swift sword is for fathers and kings, not daughters and subjects. The story of Judith and the story of Antigone have not been part of the education of daughters, as both Elizabeth Robins and Virginia Woolf point out, unless men have revised and rewritten them. It is hardly possible to read the poetry of Sappho, they both assure us, separate from centuries of scholarly calumny.

—Jane Marcus, "Art and Anger"

Why not create a new form of society founded on poverty and equality? Why not bring together people of all ages and both sexes and all shades of fame and obscurity so that they can talk, without mounting platforms or reading papers or wearing expensive clothes or eating expensive food? Would not such a society be worth, even as a form of education, all the papers on art and literature that have ever been read since the world began? Why not abolish prigs and prophets? Why not invent human intercourse? Why not try?

—Virginia Woolf, "Why?"

------------

*In

"Planetarity: Musing Modernist Studies", Susan Stanford Friedman sums up some of the changes that made the New Modernist Studies seem new: "Modernism, for many, became a reflection of and engagement with a wide spectrum of historical changes, including intensified and alienating urbanization; the cataclysms of world war and technological progress run amok; the rise and fall of European empires; changing gender, class, and race relations; and technological inventions that radically changed the nature of everyday life, work, mobility, and communication. Once modernity became the defining cause of aesthetic engagements with it, the door opened to thinking about the specific conditions of modernity for different genders, races, sexualities, nations, and so forth. Modernity became modernities, a pluralization that spawned a plurality of modernisms and the circulations among them.

When

interviewed by a reporter from the

Wall Street Journal regarding

Thomas Ligotti, Jeff VanderMeer was asked: "Can Ligotti’s work find a broader audience, such as with people who tend to read more pop horror such as Stephen King?" His response was, it seems to me, accurate:

Ligotti tells a damn fine tale and a creepy one at that. You can find traditional chills to enjoy in his work or you can find more esoteric delights. I think his mastery of a sense of unease in the modern world, a sense of things not being quite what they’re portrayed to be, isn’t just relevant to our times but also very relatable. But he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him—like Roberto Bolano. I’d put him in that camp too—the Bolano of 2666. That’s a rare feat these days.

This reminded me of a few moments from past conversations I've had about the difficulty of modernist texts and their ability to find audiences. I have often fallen into the assumption that difficulty precludes any sort of popularity, and that popularity signals shallowness of writing, even though I know numerous examples that disprove this assumption.

When I was an undergraduate at NYU, I took a truly life-changing seminar on Faulkner and Hemingway with the late Ilse Dusoir Lind, a great Faulknerian. Faulkner was a revelation for me, total love at first sight, and I plunged in with gusto. Dr. Lind thought I was amusing, and we talked a lot and corresponded a bit later, and she wrote me a recommendation letter when I was applying to full-time jobs for the first time. (I really need to write something about her. She was a marvel.) Anyway, we got to talking once about the difficulty of Faulkner's best work, and she said that she had recently (this would be 1995 or so) had a conversation with somebody high up at Random House who said that Faulkner was their most consistent seller, and their bestselling writer across the years. I don't know if this is true or not, or if I remember the details accurately, or if Dr. Lind heard the details accurately, but I can believe it, especially given how common Faulkner's work is in schools.

And this was ten years before the Oprah Book Club's "Summer of Faulkner". I love something Meghan O'Rourke wrote in

her chronicle of trying to read Faulkner with Oprah:

Going online in search of help, I worried about what I might find. What if no one liked Faulkner, or—worse—the message boards were full of politically correct protests of his attitude toward women, or rife with therapeutic platitudes inspired by the incest and suicide that underpin the book? But on the boards, which I found after clicking past a headline about transvestites who break up families, I discovered scores of thoughtful posts that were bracingly enthusiastic about Faulkner. Even the grumpy readers—and there were some, of course—seemed to want to discover what everyone else was excited about. What I liked best was that people were busy addressing something no one talks about much these days: the actual experience of reading, the nuts and bolts of it.

We often underestimate the common reader.

Which brings me to another anecdote. When I was doing my master's degree, I fell in love with the poetry of

Aimé Césaire, particularly the

Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. I was at Dartmouth, so our instructor (who later very kindly joined my thesis committee) was an expert on Césaire and had spent time in Martinique with him. I asked him how it was possible for someone who wrote such complex, thorny stuff to have become so popular among not just individuals, but whole groups of people who had not had great access to education and who may have little knowledge of modernist poetry. He said something to the effect of: Difficulty depends on what you expect, and what your context for understanding is. If your experience and perception of the world fits with that of the writer, then the form a great writer finds to express that experience and perception is going to be accessible to you, or at least accessible enough to allow you some level of basic appreciation from which to build greater appreciation. He said he'd seen illiterate people deeply, deeply moved by Césaire's poetry when it was read aloud. He knew countless people who had memorized whole passages. He himself fell in love with Césaire's work when he was at school in England, far away from home, and his roommate, who was from the Caribbean, had written (from memory) passages of the

Notebook on the ceiling of their dorm room so that it would be the last thing he saw each night and the first thing he saw each morning. Césaire may not have been an international bestseller, but his popularity is real, and is a kind any writer would be humbled by and grateful for.

I've been reading around in

Modernism, Middlebrow, and the Literary Canon: The Modern Library Series 1917-1955 by Lise Jaillant, which includes a fascinating chapter on Virginia Woolf. While the information about how

Orlando sold well from the beginning is familiar to anyone who's read much biographical material about Woolf, far more interesting and revealing is the discussion of the fate of

Mrs. Dalloway in the Modern Library edition in the US. This actually has a lot of parallel to Ligotti becoming

part of the Penguin Classics line, for, as Jaillant

writes, "The Modern Library was the first publisher's series to market Woolf as a classic writer.") During and immediately after World War II, the Modern Library edition of

Mrs. Dalloway sold quite well, at least in part because of its use in schools:

In 1941-42, Mrs. Dalloway sold four copies to every three of To the Lighthouse. This trend continued after the war, a period characterized by a huge rise in student enrolments, and an increasing number of courses on twentieth-century literature. The Modern Library edition of Mrs. Dalloway was often adopted for use in survey courses at large universities. In 1947, for example, one professor at the University of Wisconsin ordered 1,400 copies of Mrs. Dalloway, and another one at the University of Chicago ordered 800 copies of the same book. In the 1940s, Mrs. Dalloway sold around 2,800 copies a year. If we look at the twenty-year period from 1928 to 1948, Mrs. Dalloway sold 61,000 copies.

It probably would have gone on like that if the Modern Library hadn't lost the reprint rights to

Mrs. Dalloway — Harcourt/Brace had decided to start their own line of inexpensive "classic" editions (Harbrace Modern Classics). Attitudes toward modernist novels had changed, too, as Jaillant says: "...the idea that a modernist work could also be a bestseller was increasingly contested in the 1940s and 1950s, at the time when modernism was institutionalized in English departments. The popularity of

Mrs. Dalloway and

To the Lighthouse was soon forgotten, as modernism came to be seen as a difficult movement for an elite" (102). (I don't know how well

Mrs. Dalloway and

To the Lighthouse sold between 1948 and the 1970s. By 1975 or so, Woolf was championed by feminist scholars and started on her way to becoming one of the most frequently studied writers on Earth. I've been told that sales of her books were pretty dismal by the end of the 1960s, and that most of her books were out of print, but that may be more a matter of memory and perception than fact. This is something I need to look into further.)

Mrs. Dalloway and

To the Lighthouse are not easy books. They aren't

The Waves, but they're still nothing anyone would ever describe as "easy reads". (

The Waves did very well at first, since it was Woolf's first novel after

Orlando, selling just over 10,000 copies in the first six months in the UK, but it then dwindled to only a few hundred copies sold in the UK in the next six months, according to

J.H. Willis) The various editions of

Mrs. Dalloway and

To the Lighthouse still sell well today, and are not only beloved by English professors, but by all sorts of common readers who come upon them in a class or just in the course of ordinary life and find something in the pages worth wrestling with. Even

The Waves is deeply loved by many people, and it's one of the most difficult of modernist texts. But it, like all of Woolf's best writing, does things to you few, if any, other books do.

This gets back to what Jeff said about Ligotti: "he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him." If readers trust that the effort of learning to read a strange or difficult writer is worth it, then they may put forth that effort. Brains are stubborn, and sometimes resist being changed. I threw Faulkner's

Absalom, Absalom! across the room three times when I first read it. Eventually, I put in enough work that the book was able to teach me how to read it. And then we were in love, eternal love.

There's no sure pathway to such things, for writer or reader, and of course there are plenty of marvelous, difficult writers whose work has never succeeded much, if at all. In many cases, success (eventual or immediate) is a matter of packaging, and sometimes that packaging is deceptive. Look at Faulkner, for instance. His reputation among critics and scholars in the 1930s was generally high, but the only book that sold well was his sensationalist pulp novel

Sanctuary. The

Southern Agrarians (and, later,

New Critics) rather oddly reconfigured and tamed Faulkner, downplaying and flat-out misinterpreting and misrepresenting the darkness, ambiguity, and weirdness of his work. The biggest successes at this were Malcolm Cowley, who gave up left-wing politics around the time he started editing the various

Viking Portable editions of major writers, and Cleanth Brooks, who palled around with the Agrarians and helped create and promulgate New Criticism. Cowley's

Portable Faulkner presented a simplified and superficial vision of Faulkner, while Brooks's studies of Faulkner provided

(mis)interpretations of his works that made Faulkner seem like an unthreatening nostalgist, a writer palatable both to the more conservative of Southern critics and the blandly liberal Northern critics. The simplified/sanitized/superficial view of Faulkner led to a Nobel Prize and quick canonization. Faulkner himself even seems to have bought into the new, cuddly presentation — his last great work was

Go Down, Moses in 1942, with nothing written after it of comparable quality, depth, or strangeness. Some of the later books and stories are quite readable, but they're relatively shallow and often cloying. Partly, or perhaps even fundamentally, this was the result of chronic alcoholism catching up to Faulkner, but it was also a matter of his having apparently decided to write what his growing audience expected of him.

Still, even with all its simplicities and superficialities, the canonization of Faulkner allowed his work to stay in print, to receive wide distribution, and to be read. Many people probably didn't read past the Agrarian/New Critic view for decades, but I expect many others

did. (Especially people influenced by existentialism, who would have seen the darkness and even nihilism within the best writings. For a long time, and maybe still, people outside the US academy saw a deeper, stranger Faulkner than US professors and critics.) The books were available, the words could be read.

The lesson here, if there is a lesson, is that literary history is complex and doesn't easily boil down to simple oppositions like

popular vs.

difficult. And that so much depends upon how a book is sold to readers, and how readers have the opportunity to discover a book, and what they expect from it and hope from it, because what they hope and expect from a book will determine how they find their way into it, and it will further determine whether they stick with it when the way in proves challenging. If writers, publishers, critics, and teachers respect readers as intelligent beings and keep high expectations for them, some great things can happen sometimes, especially if a "difficult" book is able to stay in print for a little while, to lurk on shelves until it is discovered by the readers who need it, the readers ready to help its words live.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 9/13/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

William Plomer,

UNH,

Vera Brittain,

Elizabeth Bowen,

John Lehmann,

Winifred Holtby,

Writers,

PhD,

Christopher Isherwood,

Woolf,

Add a tag

The new school year has started, which means I've officially ended the work I did for a summer research fellowship from the

University of New Hampshire Graduate School, although there are still a few loose ends I hope to finish in the coming days and weeks. I've alluded to that work previously, but since it's mostly finished, I thought it might be useful to chronicle some of it here, in case it is of interest to anyone else. (Parts of this are based on my official report, which is why it's a little formal.)

I spent the summer studying the literary context of Virginia Woolf’s writings in the 1930s. The major result of this was that I developed

a spreadsheet to chronicle her reading from 1930-1938 (the period during which she conceived and wrote her novel

The Years and her book-length essay

Three Guineas), a tool which from the beginning I intended to share with other scholars and readers, and

so created with Google Sheets so that it can easily be viewed, updated, downloaded, etc. It's not quite done: I haven't finished adding information from Woolf's letters from 1936-1938, and there's one big chunk of reading notebook information (mostly background material for

Three Guineas) that still needs to be added, but there's a plenty there.

Originally, I expected (and hoped) that I would spend a lot of time working with periodical sources, but within a few weeks this proved both impractical and unnecessary to my overall goals. The major literary review in England during this period was the

Times Literary Supplement (TLS), but working with the TLS historical database proved difficult because there is no way to access whole issues easily, since every article is a separate PDF. If you know what you’re looking for, or can search by title or author, you can find what you need; but if you want to browse through issues, the database is cumbersome and unwieldy. Further, I had not realized the scale of material — the TLS was published weekly, and most reviews were 800-1,000 words, so they were able to publish about 2,000 reviews each year. Just collecting the titles, authors, and reviewers of every review would create a document the length of a hefty novel. The other periodical of particular interest is the

New Statesman & Nation (earlier titled

New Statesman & Athenaeum), which Leonard Woolf had been an editor of, and to which he contributed many reviews and essays. Dartmouth College has a complete set of the

New Statesman in all its forms, but copies are in storage, must be requested days in advance, and cannot leave the library.

All of this work could be done, of course, but I determined that it would not be a good use of my time, because much more could be discovered through Woolf’s diaries, letters, and reading notebooks, supplemented by the diaries, letters, and biographies of other writers. (As well as Luedeking and Edmonds’

bibliography of Leonard Woolf, which includes summaries of all of his

NS&N writings — perfectly adequate for my work.)

And so I began work on the spreadsheet. Though I chronicled all of Woolf’s references to her reading from 1930-1938, my own interest was primarily in what contemporary writers she was reading, and how that reading may have affected her conception and structure of

The Years and, to a lesser extent,

Three Guineas (to a lesser extent because her references in that book itself are more explicit, her purpose clearer). As I began the work, I feared I was on another fruitless path. During the first years of the 1930s, Woolf was reading primarily so as to write the literary essays in

The Common Reader, 2nd Series, which contains little about contemporary writing, and from the essays themselves we know what she was reading.

But then in 1933 I struck gold with this entry from 2 September 1933:

I am reading with extreme greed a book by Vera Britain [sic], called The Testament of Youth. Not that I much like her. A stringy metallic mind, with I suppose, the sort of taste I should dislike in real life. But her story, told in detail, without reserve, of the war, & how she lost lover & brother, & dabbled her hands in entrails, & was forever seeing the dead, & eating scraps, & sitting five on one WC, runs rapidly, vividly across my eyes. A very good book of its sort. The new sort, the hard anguished sort, that the young write; that I could never write. (Diary 4, 177)

Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth was published in 1933, and was one of the bestselling books of the year. It remains in print, and

a film of it was in US theatres this summer. What struck me in Woolf’s response to it was that she called it a book “I could never write” — and she did so just as

The Years was finding its ultimate form in her mind, and only months before she started to write the sections concerned with World War One. What also struck me was that her response to

Testament of Youth was in some ways similar to her infamous response to Joyce’s

Ulysses, a book she thought vulgar and a bit too obsessed with bodily functions, but which also clearly fascinated and

influenced her.

One of the things that occurred to me after reading Woolf’s note on

Testament of Youth was that

The Years is among her most physically vivid novels. Sarah Crangle

has said of it: “

The Years is a culminating point in Woolf ’s representation of the abject, as she incessantly foregrounds the body and its productions” (9). The September 2 diary entry shows that Woolf was highly aware of this foregrounding in Vera Brittain’s (very popular) book, and her framing of herself as part of an older generation and someone unable to write in such a way may have worked as a kind of challenge to herself.

I then sought out

Testament of Youth and read it (all 650 pages) with Woolf in mind. What qualities of this book caused it to run so rapidly across her eyes? She herself wrote in a letter to her friend Ethel Smyth on September 6: “Vera Brittain has written a book which kept me out of bed till I'd read it. Why?” (

Letters 5, 223). I asked

Why? myself quite a bit as I began reading

Testament, because the first 150 pages or so are not anything a contemporary reader is likely to find gripping. And yet reading with Woolf in mind made it quite clear: The first section of

Testament is all about Vera Brittain’s attempt to get into Oxford, and Woolf herself had been denied (because of her gender) the university education her brothers received, a fact that bothered her throughout her life. The ins and outs of Oxford entrance exams may not be scintillating reading for most people, but for a woman who had never even been able to consider taking those exams, and yet dearly yearned for an educational experience of the sort men were allowed,

Testament provides a vivid vicarious experience. The central part of the book, about Brittain’s experience as a nurse during the war, also provided vicarious experience for Woolf, whose own experience of the war was far less immediate. Woolf lost some friends and distant relations in the war (most notably the poet

Rupert Brooke, with whom she was friendly and may have had some romantic feelings for), but did not experience anything like the trauma that Brittain did: the loss of all of her closest male friends, including her fiancé and her brother. Nor did Woolf see mutilated bodies and corpses, as Brittain did.

Woolf and Brittain were very much aware of each other — Brittain, in fact, makes passing mention to

A Room of One’s Own in

Testament of Youth — and

the first book-length study of Woolf in English was written by Brittain’s great friend

Winifred Holtby (an important character in the latter part of

Testament; after Holtby’s death in 1935, Brittain wrote a biography of her titled

Testament of Friendship, which Woolf thought presented too flat a view of Holtby, a person she seems to have come to respect, though she didn’t much like Holtby’s writing). There is, though, very little scholarship on Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby together, perhaps because Brittain and Holtby seem like such different writers from Woolf in that they were much more committed to a kind of social realism that Woolf abjured. There's a lot of work still remaining to be done on the three writers together. Not only is

Testament of Youth a book that can be brought into conversation with

The Years, but Brittain’s novel

Honourable Estate, published one year before

The Years, has numerous similarities in its scope and goals to

The Years, though it seems almost impossible that it had any direct influence, since it was published when Woolf was doing final revisions of

The Years and she didn’t much like Brittain’s writing, so was unlikely to have read the book (I’ve certainly found no evidence that she did).

In the course of this research, I soon discovered that UNH’s own emerita professor Jean Kennard published a book in 1989 titled

Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby: A Working Partnership, the first (and still only) scholarly study of the two writers together. I read the book avidly, as I had taken a seminar on Virginia Woolf with Prof. Kennard in the spring of 1998 at UNH as an undergraduate, and I owe much of my love of Woolf to that seminar. The book looks closely at each authors’ writings and proposes that their friendship was a kind of lesbian relationship, an idea that has been somewhat controversial (Deborah Gorham’s

study of Brittain offers a nuanced response).

In addition to exploring the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, I looked at three writers of the younger generation whom Woolf knew personally and paid close attention to:

John Lehmann,

William Plomer, and

Christopher Isherwood. Lehmann worked for the Woolfs at their Hogarth Press in the early thirties, left for a while, then returned and took a more prominent role, buying out Virginia Woolf’s share of the press in the late 1930s. Lehmann and the Woolfs had an often contentious relationship, as he was very interested in the work of younger writers, particularly poets, and Virginia Woolf especially had more mixed feelings about the directions that writers such as

W.H. Auden and

Stephen Spender were going in. Woolf wrote a relatively long letter to Spender on 25 June 1935 about his recent collection of criticism,

The Destructive Element, in which she positions her own aesthetics both in sympathy and tension with Spender’s, particularly Spender’s perspective on

D.H. Lawrence.

Spender’s defense of Lawrence helps explain some of Virginia Woolf’s resistance to the younger writer’s aesthetic. One of the insights that my work this summer provided (at least to me) was the extent to which Woolf thought about, and was bothered by, Lawrence, who died in March 1930. (In 1931, Woolf wrote "Notes on D.H. Lawrence", primarily about

Sons and Lovers.) She had complex feelings about Lawrence’s writing — disgust, frustration, and annoyance mixed with fascination. She often said she hadn’t read much of Lawrence’s work, but from the amount of references she makes to it, and the number of critical studies and memoirs about Lawrence that she read and commented on, I don’t think her protestations of not having read much of Lawrence are quite accurate — she was clearly familiar with all his major novels, and I suspect that in her letters she downplayed this familiarity as a hedge against the strong feelings of correspondents who thought Lawrence to be among the greatest British novelists of the age. Lawrence’s work was very much on Woolf’s mind in the first years of the 1930s, and it therefore seems likely to me that

The Years was also conceived as a kind of response to

The Rainbow and

Women in Love in particular. But that's more hunch than anything, and this is a topic for more study.

John Lehmann introduced Christopher Isherwood to the Woolfs, and encouraged them to publish his second novel,

The Memorial, which they did. In 1935, they also published his first Berlin novel,

Mr. Norris Changes Trains (in the US,

The Last of Mr. Norris), then in 1937 his novella

Sally Bowles and in 1939 the interlinked stories of

Goodbye to Berlin (later to be adapted as the play

I Am a Camera and the musical

Cabaret). Isherwood’s experience of Berlin in the 1930s was of particular interest to the Woolfs, who themselves (with some trepidation, given the fact that Leonard was Jewish) traveled through Germany briefly in 193

5 to see the extent of the spread of Nazism.

William Plomer was a writer the Woolfs published in 1926, and who became close friends with Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender. Plomer was born to British parents in South Africa, attended schools in England, then returned to Johannesburg, where he finished college and then worked as a farmhand and then with his family at a trading post in Zulu lands. It was there that he wrote

Turbott Wolfe, based partly on his experience at the trading post and partly on his friendships among painters and artists in Johannesburg. He was only 20 years old when he sent it to the Woolfs, and they printed it soon after

Mrs. Dalloway. Leonard was particularly interested in African politics and anti-imperialism, and the novel’s theme of racial mixing as a solution to the tensions between races in South Africa was iconoclastic and proved controversial. Plomer left South Africa and spent time in Japan, experiences which informed his later novel (also published by the Woolfs)

Sado, a story that included homosexual overtones. (Like Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender, Plomer was gay, though less openly and comfortably so than his friends.) Plomer would publish a number of books with the Woolfs, including some well-received volumes of poetry, but eventually moved to publish his fiction and autobiographies with Jonathan Cape, where he was an editorial reader (and convinced Cape to publish the first novel of his friend Ian Fleming,

Casino Royale — a very young Fleming, in fact, had written Plomer a fan letter after

reading Turbott Wolfe, the two became friends when Fleming was a journalist in the 1930s, and eventually Fleming dedicated

Goldfinger to Plomer).

Plomer became a more frequent member of the Woolf’s social circle than any other young writer that I’ve noticed, and Virginia Woolf seems to have felt almost motherly toward him. Aesthetically, he was far less threatening than the other young men of the Auden generation, and though his novels can easily be read through a queer frame, he was more circumspect about the topic than his peers.

As the summer wound down and I continued to work through Woolf’s diaries and letters, I became curious about the place of

Elizabeth Bowen’s work in her life. Woolf and Bowen were friends, and Bowen’s work shows many Woolfian qualities, but Woolf made very few conclusive statements about Bowen’s novels that I have been able to find so far — mostly, she acknowledge Bowen sending her each new novel, and always said she would read it soon, but I have only found definite evidence that she read one,

The House in Paris, which is set soon after World War I and, like

Mrs. Dalloway, takes place over the course of a single day. Like the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, the relationship between the works of Woolf and Bowen seems to be ripe for further study.