new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: bradley, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: bradley in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 4/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

oed,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

bradley,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Henry Bradley,

spelling reform,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Last week I wrote about Henry Bradley’s role in making the OED what it is: a mine of information, an incomparable authority on the English language, and a source of inspiration to lexicographers all over the world. New words appear by the hundred, new methods of research develop, and many attitudes have changed in the realm of etymology since the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, but nothing said in the great dictionary has become useless, even though numerous conjectures and formulations have to be revised.

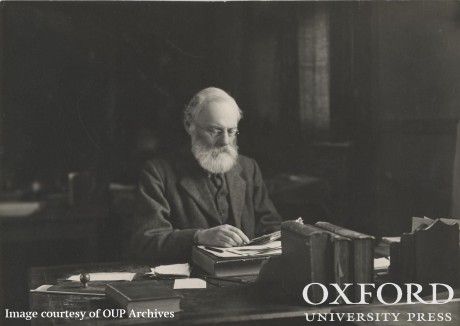

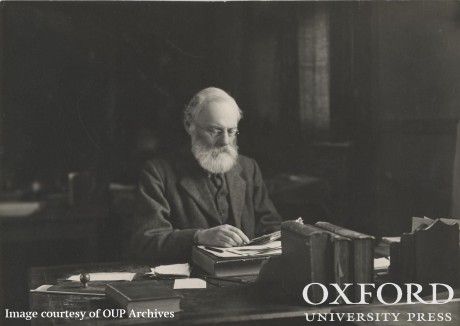

Unfortunately, the world knows little about those who did all the work. It will probably not be an exaggeration to say that before Katharine Maud Elisabeth Murray wrote a book on her grandfather (1977) and gave it the wonderful title Caught in the Web of Words, few people outside the profession had any notion of who James A. H. Murray, the OED’s senior editor, was. Samuel Johnson’s definition of a lexicographer as a harmless drudge has been trodden to death by authors who live on borrowed wit. Alas, very often the only way to honor a distinguished “drudge” is to publish a short obituary, usually forgotten on the same day. As I mentioned last time, Bradley had better luck: a posthumous volume of his collected works appeared in 1928. I was happy to see his archival picture in my post. Many eminent scholars of that epoch were photographed in the same position, so that they look like venerable old twins, writing desk, glasses, beard and all. Yet this picture is different from the one reproduced in the 1928 book.

How harmless lexicographers are I cannot tell. It seems that, with regard to character, this profession, like any other, is, to use the most popular word of our time, diverse. In any case, lexicographers do not only shuffle index cards and sit at computers, trying to disentangle themselves from the web of words: they have opinions about many things, not related directly to the art of dictionary making. For example, both Bradley and Skeat had non-trivial ideas about spelling reform. Today I will summarize Bradley’s views. Skeat’s turn will come round next Wednesday. To begin with, Bradley, who made his thoughts public in 1913, was an opponent of Simplified Spelling, but he addressed only one side of the reform, namely the proposal that phonetic spelling should be adopted. In making his position clear, he advanced several perfectly valid arguments but overlooked perhaps the most important aspect of the problem.

In one respect, Bradley was decades ahead of his time. He insisted that the written form of Modern English and of any language using letters, far from being a mechanical transcript of oral speech, has a life of its own. This is perfectly true. Much later, the members of the Prague Linguistic Circle, a great school of European structuralism, made the same point. Bradley wrote: “Among peoples in which many persons write and read much more than they speak and hear, the written language tends to develop more or less independently of the spoken language.” He referred with admiration to the epoch of ideographic writing, when characters were pictures. Even today, he stated, we never read letter by letter, but grasp whole words. So we do, and for this reason we tend to overlook typos. Bradley did not object to many English words being ideograms, or images that have to be memorized and remain independent of the sounds of which they consist. Many scholarly words are familiar to us only from books; they are hardly ever pronounced, so may they preserve their familiar form, he said.

Bradley made his attitude clear: English spelling is an heir to an age-long tradition and should be reformed with care. Sounds, he added, change, and, “when change of pronunciation had made a spoken word ambiguous, the retention of the old unequivocal written form is a great practical convenience. It makes the written language, so far, a better instrument of expression than the spoken language.” Sometimes he was forcing open doors, but in his days there was no theory of orthography, and his point is well taken. Indeed, modern spelling has several (though hardly equally important) functions. For example, it may connect related words, in violation of the phonetic principle. Thus, k- in know ~ knowledge is a nuisance (I was almost tempted to write knuisance), but it should probably be retained by reformers because k- is pronounced in acknowledge (however, I am afraid that aknowledge would be quite enough).

It may be convenient that in some situations we bow to the ideographic principle and have write, wright ~ Wright, and rite. The recent invention of phishing is characteristic: it designates fishing for customers in muddy waters, fishing with an evil flourish (phlourish?). Bradley did not cite rite and its kin, but referred to hole and whole, son and sun, night and knight among numerous other homophones, which are not homographs. (Homophones sound alike; homographs are spelled alike.) He quoted the line Nor burnt the grange, no buss’d the milking-maid (buss means “kiss”) and remarked that Tennyson would not have agreed to write bust for bus’t; hence the virtue of the apostrophe. When words are spelled differently, we are apt to ascribe different meanings to them. This is again correct. Bradley recalled the case of grey versus gray (see my post on this word): many people, especially artists, when asked about their thoughts on those adjectives, replied that they associate gray and grey with different colors.

Bradley agreed that the spelling of some words should be changed. He admitted that it may be useful to teach children some variant of phonetic spelling before introducing them to letters, for this would make them aware of the sounds they pronounce. But phonetic spelling as the aim of a sweeping reform was unacceptable to him. I am all for simplifying English spelling, but I think Bradley was right—not so much for theoretical as for practical reasons. The English speaking world will never agree to a revolution, and promoting a hopeless cause is a waste of time. But the most interesting aspect of Bradley’s attack on the reform is his general attitude. He addressed only the needs of those who had already mastered the intricacies of English spelling. Obviously, to someone who learned that choir is quire and a playwright is not a playwrite, even though this person writes plays, any change will be an irritation. But the advocates of the reform have the uneducated in mind. They and Bradley speak at cross-purposes.

Strangely, only one aspect of English spelling worried Bradley: the existence of many words like bow as in make a low bow and bow in bow and arrow. This situation, he thought, had to be changed, even though he could not offer any advice. In his opinion, words that sounded differently had to be spelled differently. “The task of rectifying these anomalies, and of making the many readjustments with their correction will render necessary, will require great ingenuity and thought.” Consequently, homophones may be spelled differently (right, write, wright, Wright, rite), but homographs should be homophones (for this reason, bow1 and bow2, read and its past read, etc. need different visual representations).

The rest of Bradley’s argumentation against the reformers is traditional (English speakers pronounce words differently: for example, lord and laud are not homophones with 90% of English speakers, and so forth) and need not be discussed here, but we will return to it in connection with Skeat’s passionate defense of the reform.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Theodore Roosevelt cartoon via Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt.

The post Henry Bradley on spelling reform appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/9/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

bradley’s,

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

oed,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Henry Bradley,

word origins,

oxford english dictionary,

bradley,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

At one time I intended to write a series of posts about the scholars who made significant contributions to English etymology but whose names are little known to the general public. Not that any etymologists can vie with politicians, actors, or athletes when it comes to funding and fame, but some of them wrote books and dictionaries and for a while stayed in the public eye. Ernest Weekley authored not only an etymological dictionary (a full and a concise version) but also multiple books on English words that were read and praised widely in the twenties and thirties of the twentieth century. Walter Skeat dominated the etymological scene for decades, and his “Concise Dictionary” graced many a desk on both sides of the Atlantic. James Murray attained glory as the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. (Curiously, for a long time people, at least in England, used to say that words should be looked up “in Murray,” as we now say “in Skeat” or “in Webster.” Not a trace of this usage is left. “Murray” yielded to the anonymous NED [New English Dictionary] and then to OED, with or without the definite article).

Those tireless researchers deserved the recognition they had. But there also were people who formed a circle of correspondents united by their devotion to some journal: Athenaeum, The Academy, and their likes. Most typically, the same subscribers used to send letters to Notes and Queries year in, year out. As a rule, they are only names to me and probably to most of our contemporaries, but the members of that “club” often knew one another or at least knew who the writers were, and being visible in Notes and Queries amounted to a thin slice of international fame. Having run (for the sake of my bibliography of English etymology) through the entire set of that periodical twice, I learned to appreciate the correspondents’ dedication to scholarship and their erudition. I learned a good deal about their way of life, their libraries, and their antiquarian interests, but not enough to write an entertaining essay devoted to any one of them. That is why my series died after the first effort, a post on Dr. Frank Chance (Dr. means “medical doctor” here), and I still hope that one day Oxford University Press will publish a collection of his excellent short articles on English and French subjects.

To be sure, Henry Bradley is not an obscure figure, but even in his lifetime he was never in the limelight. And yet for many years he was second in command at the OED and, when Murray died, replaced him as NO. 1. In principle, the OED, conceived as a historical dictionary, did not have to provide etymologies. But the Philological Society always wanted origins to be part of the entries. Hensleigh Wedgwood was at one time considered as a prospective Etymologist-in-Chief, but it soon became clear that he would not do: his blind commitment to onomatopoeia and indifference to the latest achievements of historical linguistics disqualified him almost by definition despite his diligence and ingenuity. Skeat may not have aspired for that role. In any case, James Murray decided to do the work himself. That he turned out to be such an astute etymologist was a piece of luck.

Beginning with 1884, Bradley became an active participant in the dictionary. According to Bridges, in January 1888 he sent in the first instalment of his independent editing (531 slips). In the same year he was acknowledged as Joint Editor, responsible for his own sections, in 1896 he moved to Oxford, and from 1915, after the death of Murray in July of that year, he served as Senior Editor. In 1928 Clarendon Press published The Collected Papers of Henry Bradley, With a Memoir by Robert Bridges, and it is from this memoir that I have all the dates. About the move to Oxford, Bridges wrote: “He definitely entered into bondage and sold himself to slave henceforth for the Dictionary.” (How many people still remember the poetry of Robert Bridges?)

James Murray was a jealous man. He might have preferred to go on without a senior assistant, but even he was unable to do all the editing alone. It could not be predicted that Bradley would trace the history of words, inherited and borrowed, so extremely well. Once again luck was on the side of the great dictionary. In 1923, when Bradley died, not much was left to do. Even today, despite a mass of new information, the appearance of indispensable dictionaries and databases (to say nothing of the wonders of technology), as well as the publication of countless works on archeology, every branch of Indo-European, and the structure of the protolanguage and proto-society, the original etymologies in the OED more often than not need revision rather than refutation. This fact testifies to Murray’s and Bradley’s talent and to the reliability of the method they used.

Bradley joined the ictionary after Murray read his review of the first installments of the OED (The Academy, February 16, pp. 105-106, and March 1, pp. 141-142; I am grateful to the OED’s Peter Gilliver for checking and correcting the chronology). Bridges wrote about that review: “…its immediate publication revealed to Dr. Murray a critic who could give him points.” But today, 140 years later, one wonders what impressed Murray so much in Bradley’s remarks and what points “the critic” could give him. Bradley did not conceal his admiration for what he had seen, suggested a few corrections, and expressed the hope that “the work [would] be carried to its conclusion in a manner worthy of this brilliant commencement.” It can be doubted that Murray melted at the sight of the compliments: with two exceptions, everybody praised the first fascicles, and those who did not wrote mean-spirited reports. More probably, he sensed in Bradley someone who had a thorough understanding of his ideas and a knowledgeable potential ally (Bradley’s pre-1883 articles were neither numerous nor earth shattering). If such was the case, he guessed well.

Finding word origins was only one small (even if the trickiest) part of the editors’ duties, but my subject is limited to this single aspect of their activities. The title of Bradley’s posthumous volume, The Collected Papers, should not be mistaken for The Complete Works. Nor was such a full collection needed, though some omissions cause regret. Like Murray, Bradley wrote many short notes (especially often to The Academy, of which long before his move to Oxford he was editor for a year). My database contains sixty-five titles under his name. Here are some of them: “Two Mistakes in Littré’s French Dictionary,” “Obscure Words in Middle English,” “The Etymology of the Word god,” “Dialect and Etymology” (the latter in the Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society; Bradley was born in Manchester, so not in Yorkshire), numerous reviews and equally numerous reports, some of whose titles evoke today unexpected associations, as, for example, “F-words in NED” (the secretive year of 1896, when the F-word could not be included!).

Bradley had edited and revised the only full Middle English dictionary then in use. The modest reference to “obscure words” gives no idea of how well he knew that language. And among The Collected Papers the reader will find, among others, his contributions on Beowulf and “slang” to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, ten essays on place names (one of his favorite subjects), and a whole section of literary studies. Those deal with Old and Middle English, and in several cases his opinion became definitive. Bradley’s tone was usually firm (he made no bones about disagreeing with his colleagues) but courteous. Although he sometimes chose to pity an indefensible opinion, the vituperative spirit of nineteenth-century British journalism did not rub off on him. Nor was he loath to admit that his conclusions might be wrong. Temperamentally, he must have been the very opposite of Murray.

One of Bradley’s papers is of special interest to us, and it was perhaps the most influential one he ever wrote. It deals with the chances of reforming English spelling. I will devote a post to it next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of OUP Archives.

The post Unsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923) appeared first on OUPblog.

Posted on 10/11/2009

Blog:

The Leaky Cauldron

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

News,

Products,

OotP Film,

Movies,

Radcliffe,

Video Games,

Lynch,

HP Cast,

Lewis,

HBP Film,

Smith,

Trailers,

Thompson,

Wright,

Watson,

Murray,

Enoch,

root,

Gambon,

Felton,

DH Film,

Grint,

Fiennes,

Coltrane,

Film Images,

GoFFilm,

Griffiths,

Home Video / DVD,

Phelps,

Rickman,

Gleeson,

Bradley,

Staunton,

Leung,

Add a tag

As announced earlier, WB will be releasing Harry Potter: Wizarding World DVD game on December 1st, just a few days before the release of Half-Blood Prince and the special Ultimate Collector's editions DVDs. As such Amazon.com has a brand new trailer for the DVD game which you can see right here in our Video galleries. Last month we told of the details for the game which covers elements from Har...

Read the rest of this post

By: Rebecca,

on 9/15/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

war,

American History,

A-Featured,

Vietnam,

Mark,

World History,

perspective,

prophecy,

Bradley,

Philip,

Mark Philip Bradley,

Add a tag

Mark Philip Bradley is Associate Professor of History at the University of Chicago. His most recent book, Vietnam at War, looks at how the Vietnamese themselves experienced the conflicts,  showing how the wars for Vietnam were rooted in fundamentally conflicting visions of what an independent Vietnam should mean that in many ways remain to this day. In the excerpt below, from the introduction, Bradley begins to paint the Vietnamese perspective of the conflict.

showing how the wars for Vietnam were rooted in fundamentally conflicting visions of what an independent Vietnam should mean that in many ways remain to this day. In the excerpt below, from the introduction, Bradley begins to paint the Vietnamese perspective of the conflict.

In the early 1990 a short story by a young author, Tran Huy Quang, entitled ‘The Prophecy’ (’Ling Nghiem’), appeared to great interest in Hanoi. It told the tale of a young man named Hinh, the son of a mandarin, who longed to acquire the magical powers that would one day enable him to lead his countrymen to their destiny. The destiny itself does not particularly concern Hinh, but he is intent upon leading the Vietnamese people to it. In a dream one evening, Hinh meets a messenger from the gods, who tells him to seek out a small flower garden. Once he reaches the garden, Hinh is told, he should walk slowly with his eyes fastened on the ground to ‘look for this’. It will only take a moment, the messenger tells Hinh, and as a result he will ‘possess the world’.

When he awakens, Hinh finds the flower garden and begins to pace, looking downward. Slowly a crowd gathers, first children, then the disadvantaged of Vietnamese society: unemployed workers, farmers who had left their poor rural villages to find work in the city, cyclo drivers, prostitutes, beggars, and orphans. Watching Hinh, they ask in turn, ‘What are you looking for?’ He replies, ‘I am looking for this.’ Hopeful of turning up a bit of good luck, they join him, and soon multitudes of people are crawling around in the garden. Hinh looks around at the crowd searching with him and believes the prophecy has been fulfilled: he possesses the world. With that realization Hinh goes home.

To Vietnamese readers the story was immediately recognized as a parable, with Hinh representing Ho Chi Minh, the pre-eminent leader of the twentieth-century Vietnam. The prophecy was seen as coming from a secular god, Karl Marx. ‘This’ was the promise of a socialist future, which the author of ‘The Prophecy’ and many of his readers in Hanoi increasingly believed to be a hollow one. For them, socialist ideals did enable Vietnamese revolutionaries to develop a mass following and establish an independent state, throwing off a century of French colonial rule. But in the aftermath of some thirty years of war against the French and the Americans, their hopes for a more egalitarian and just society appeared to remain unfulfilled.

…In truth, there were many Vietnam wars, among them an anti-colonial war with France, a cold war turned hot with the United States, a civil war between North and South Vietnam and among southern Vietnamese, and a revolutionary war of ideas over the vision that should guide Vietnamese society into the post-colonial future. The contest of ideas began long before 1945 and persists to the present day in yet another war, this one of memory over the legacies of the Vietnam wars and the stakes of remembering and forgetting them.

For most Vietnamese, the coming of French colonialism in the late nineteenth century raised profound questions about their very survival as a people and pointed to the need to rethink fundamentally the neo-Confucian political and social order upon which Vietnamese society has rested. As one young Vietnamese asked in a 1907 poem:

Why is the roof over the Western universe the broad land and skies;

While we cower and confine ourselves to a cranny in our house?

Why can they run straight, leap far,

While we shrink back and cling to each other?

Why do they rule the world,

While we bow our heads as slaves?

Throughout the twentieth century, in both war and at peace, and into the twenty-first century, the Vietnamese have searched for answers to the predicaments posed by colonialism and the struggle for independence. As they have done so, a variety of Vietnamese actors have appropriate and transformed a fluid repertoire of new modes of thinking about the future - social Darwinism, Marxist-Leninism, social progressivism, Buddhist modernism, constitutional monarchy, democratic republics, illiberal democracies, and market capitalism to name just a few - to articulate and enact visions for the post-colonial transformation of urban and rural Vietnamese society. But the end of the Vietnam wars did not bring a final resolution to these competing visions. When North Vietnamese tanks entered Saigon on 30 April 1975 to take the surrender of the American-backed South Vietnamese government, Vietnam was reunified as a socialist state. The long war for independence was over. Yet even today, as the searchers in ‘The Prophecy’ suggest, the meanings according to ‘running straight and leaping far’ remain deeply contested. In one of many present-day paradoxes, the Vietnamese state seeks to develop a market economy as it maintains its commitment to socialism, while an increasingly heterodox Vietnamese civil society simultaneously embraces the global economy, years for the unfulfilled promises of socialist egalitarianism, and reinvents many of the spiritual and familial practices the socialist state spent the war years trying to stamp out. Indeed, a walk today through a typical city block at the centre of Hanoi or Saigon, a block in which a refurbished Buddhist temple might be flanked by a Seven-Eleven store on one side and the local community party headquarters on the other, quickly reveals these everyday contradictions and tensions…

TLC is sending good wishes today to actor David Bradley (Argus Filch) who is celebrating his 67th birthday. Cheers, David!

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Love how your living room turned out!is the paint color you chose also Benjamin Moore? it is lovely -nice and airy

Thank you! Yes, both colours I mentioned are Benjamin Moore.

Welcome home! so far so good, it looks great!

I love those curtains! And I'm pretty sure Green Tint is one of the colors I have in my bedroom. It's quite soothing.

Your living room is lovely! Really love your color choices. Looking forward to seeing more.