new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: henry james, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 19 of 19

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: henry james in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Eric Bennett has an MFA from

Iowa, the MFA of MFAs. (He also has a Ph.D. in Lit from Harvard, so he is a man of fine and rare academic pedigree.) Bennett's recent book

Workshops of Empire: Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing during the Cold War is largely about the Writers' Workshop at Iowa from roughly 1945 to the early 1980s or so. It melds, often explicitly,

The Cultural Cold War with

The Program Era, adding some archival research as well as Bennett's own feeling that the work of politically committed writers such as Dreiser, Dos Passos, and Steinbeck was marginalized and forgotten by the writing workshop hegemony in favor of individualistic, apolitical writing.

I don't share Bennett's apparent taste in fiction (he seems to consider Dreiser, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, etc. great writers; I don't), but I sympathize with his sense of some writing workshops' powerful, narrowing effect on American fiction and publishing for at least a few decades. He notes in his conclusion that the hegemonic effect of Iowa and other prominent programs seems to have declined over the last 15 years or so, that Iowa in recent years has certainly become more open to various types of writing, and that even when Iowa's influence was at an apex, there were always other sorts of programs and writers out there — John Barth at Johns Hopkins, Robert Coover at Brown, and Donald Barthelme at the University of Texas are three he mentions, but even that list shows how narrow in other ways the writing programs were for so long: three white hetero guys with significant access to the NY publishing world.

What Bennett most convincingly shows is how the discourse of creative writing within U.S. universities from the beginning of the Cold War through at least to the 1990s created a field of limited, narrow values not only for what constitutes "good writing", but also for what constitutes "a good writer". It's a tale of parallel, and sometimes converging, aesthetics, politics, and pedagogies. Plenty of individual writers and teachers rejected or rebelled against this discourse, but for a long time it did what hegemonies do: it constructed common sense. (That common sense was not only in the workshops — at least some of it made its way out through writing handbooks, and can be seen to this day in pretty much all of the popular handbooks on how to write, including Stephen King's

On Writing.)

Some of the best material in

Workshops of Empire is not its Cold War revelations (most of which are known from previous scholarship) but in its careful limning of the tight connections between particular, now often forgotten, ideas from before the Cold War era and what became acceptable as "good writing" later. The first chapter, on the

"New Humanism", is revelatory, especially in how it draws a genealogy from

Irving Babbitt to Norman Foerster to

Paul Engle and

Wallace Stegner. Bennett tells the story of New Humanism as it relates to New Criticism and subsequently not just the development of workshop aesthetics, but of university English departments in the second half of the 20th century generally, with New Humanism adding a concern for ethical propriety ("the question of the relation of the goodness of the writing to the goodness of the writer") to New Criticism's cold formalism:

Whereas the New Criticism insisted on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the poem or story — every word counted — the New Humanism focused its attention on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the humanistic subject. It did so not as a kind of progressive-educational indulgence but in deference to the wholeness of the human person and accompanied by a strict sense of good conduct. (29-30)

This mix was especially appealing to the post-WWII world of anti-Communist liberalism, a world scarred by the horrors of Nazism and Stalinism, and a United States newly poised to inflict its empire of moral righteousness across the world.

For all of Bennett's gestures toward Marxism and anti-imperialism, he seems to share some basic assumptions about the power of literature with the men of the Cold War era he disdains as conservatives. In the book's conclusion, he writes:

It remains an open question just how much criticism some or all American MFA programs deserve for contributing to the impasse of neoliberalism — the collective American disinclination to think outside narrow ideological commitments that exacerbate — or at the very least preempt resistance to — the ugliest aspects of the global economy. Those narrow commitments center, above all, on an individualism, economic and otherwise, vastly more powerful in theory and public rhetoric than in fact. We encourage ourselves to believe that we matter more than we do and to go it alone more than we can. This unquestioned inflation of the personal begs, in my opinion, the kinds of questions that must be asked before any reform or solution to some seriously pressing problems looks likely to be found. (173)

This is almost comically self-important in its idea that MFA programs might (he hopes?) have enough cultural effect that if only they had been more willing to teach students to write like Thomas Wolfe and John Steinbeck, then maybe we could conquer neoliberalism! One moderately popular movie has more cultural effect than piles and piles of books written by even the famous MFA people. If you want to fight neoliberalism, your MFA and your PhD (from Harvard!) aren't likely to do anything, sorry to say. If you want to fight neoliberalism ... well, I don't know. I'm not convinced neoliberalism

can be fought, though we might be able to find

an occasional escape in aesthetics. The idea that Books Do Big Things In The World is one that Bennett shares with his subjects; he'd just prefer they read different books.

As self-justifying delusions go, I suppose there are worse, and all of us who spend our lives amidst writing and reading believe to some extent or another that it's worthwhile, or else we wouldn't do it. But "worthwhile" is far from "world-changing". (Rx: Take a couple

Wallace Shawn plays and call me in the morning.)

Despite this, Bennett's concluding chapter had me raising my fist in solidarity, because no matter what our personal tastes in fiction may be, no matter how much we may disagree about the extent to which writing can influence the world, we agree that writing pedagogy ought to be diverse and historically informed in its approach.

Bennett shows some of the forces that imposed a common shallowness:

There was, in the second wave of programs — the nearly fifty of them founded in the 1960s — little need to critique the canon and smash the icons. To the contrary, the new roster of writing programs could thrive in easy conscience. This was because each new seminar undertook to add to the canon by becoming the canon. The towering greats (Shakespeare, Milton, Whitman, Woolf, whoever) diminished in influence with each passing year, sharing ever more the icon's niche with contemporary writers. In 1945, in 1950, in 1955, prospective poets and novelists looked to the neverable pantheon as their competition. In 1980, in 1990, in 2015, they more often regarded their published teachers or peers as such. (132)

That's polemical, and as such likely hyperbolic, but it suggests some of the ways that some writing programs may have capitalized on the culture of narcissism that has only accelerated via social media and

is now ripe for economic exploitation. I don't think it's a crisis of the canon — moral panics over the Great Western Tradition are academic Trumpism — so much as a crisis of literary-historical knowledge. Aspiring writers who are uninterested in reading anything written before they were born are nincompoops. Understandably and forgiveably so, perhaps (U.S. culture is all about the current whizbang thing, and historical amnesia is central to the American project), but too much writing workshop pedagogy, at least of the recent past, has been geared toward encouraging nincompoopness. As Bennett suggests, this serves the interests of American empire while also serving the interests of the writing world. It domesticates writers and makes them good citizens of the nationalistic endeavor.

Within the context of the book, Bennett's generalizations are mostly earned. What was for me the most exciting chapter shows exactly the process of simplification and erasure he's talking about. That chapter is the final one before the conclusion: "Canonical Bedfellows: Ernest Hemingway and Henry James". Bennett's claim here is straightforward: The consensus for what makes writing "good" that held at least from the late 1940s to the end of the 20th century in typical writing workshops and the most popular writing handbooks was based on teachers' knowledge of Henry James's writing practices and everyone's veneration of Hemingway's stories and novels.

For Bennett, Hemingway became central to early creative writing pedagogy and ideology for three basic reasons: "he fused together a rebellious existential posture with a disciplined relationship to language, helping to reconcile the avant-garde impulse with the classroom", "he offered in his own writing...a set of practices with the luster of high art but the simplicity of any good heuristic", and "he contributed a fictional vision whose philosophical dimensions suited the postwar imperative to purge abstractions from literature" (144). Hemingway popularized and made accessible many of the innovations of more difficult or esoteric writers: a bit of Pound from Pound's Imagist phase, some of Stein's rhythms and diction, Sherwood Anderson's tone, some of the early Joyce's approach to word patterns... ("He was possibly the most derivative

sui generis author ever to write," Bennett says. Snap!) Hemingway's lifestyle was at least as alluring for post-WWII male writers and writing teachers as his writing style: he was macho, war-scarred, nature-besotted in a Romantic but also carnivorous way. He was no effete intellectual. If you go to school, man, go to school with Papa and you'll stay a man.

The effect was galvanizing and long-term:

Stegner believed that no "course in creative writing, whether self administered or offered by a school, could propose a better set of exercises" than this method of Hemingway's. Aspirants through to the present day have adopted Hemingway's manner on the page and in life. One can stop writing mid-sentence in order to return with momentum the following morning; aim to make one's stories the tips of icebergs; and refrain from drinking while writing but aim to drink a lot when not writing and sometimes in fact drink while writing as one suspects with good reason that Hemingway himself did, despite saying he didn't. One can cultivate a world-class bullshit detector, as Hemingway urged. One can eschew adverbs at the drop of a hat. These remain workshop mantras in the twenty-first century. (148)

Clinching the deal, the Hemingway aesthetic allowed writing to be gradeable, and thus helped workshops proliferate:

Hemingway's methods are readily hospitable to group application and communal judgment. A great challenge for the creative writing classroom is how to regulate an activity ... whose premise is the validity and importance of subjective accounts of experience. The notion of personal accuracy has to remain provisionally supreme. On what grounds does a teacher correct student choices? Hemingway offered an answer, taking prose style in a publicly comprehensible direction, one subject to analysis, judgment, and replication. ... One classmate can point to metaphors drawn from a reality too distant from the characters' worldview. Another can strike out those adverbs. (151)

Bennett then points out that the predecessors of the New Critics, the conservative Southern Agrarians, thought they'd found in Hemingway almost their ideal novelist (alas, he wasn't Southern). "The reactionary view of Hemingway," Bennett writes, "became the consensus orthodoxy." Hemingway's concrete details don't offer clear messages, and thus they allowed his work to be "universal" — and universalism was the ultimate goal not only of the Southern Agrarians, but of so many conservatives and liberals after WWII, when art and literature were seen as a means of uniting the world and thus defeating Communism and U.S. enemies. "Universal" didn't mean

actually universal in some equal exchange of ideas and beliefs — it meant imposing American ideals, expectations, and dreams across the globe. (And consequently opening up the world to American business.)

Such a discussion of how Hemingway influenced creative writing programs made me think of other ways complex writing was made appealing to broad audiences — for instance, much of what Bennett writes parallels with some of the ideas in work such as

Creating Faulkner's Reputation by Lawrence H. Schwartz and especially

William Faulkner: The Making of a Modernist, where Daniel Singal

proposes that Faulkner's alcoholism, and one alcohol-induced health crisis in November 1940 especially, turned the last 20 years of Faulkner's life and writing into not only a shadow of its former achievement, but a mirror of the (often conservative) critical consensus that built up around him through the 1940s. Faulkner became teachable, acceptable, "universal" in the eyes of even conservative critics, as well as in Faulkner's own pickled mind, which his famous

Nobel Prize banquet speech so perfectly shows.

(Thus some of my hesitation around Bennett's too easy use of the word "modernist" throughout

Workshop of Empire — the strain of Modernism he's talking about is a sanitized, domesticated, popularized, easy-listening Modernism. It's Hemingway, not Stein. It's late Faulkner, not

Absalom, Absalom!. It's white, macho-male, heterosexual, apolitical. The influence seems clear, but it chafes against my love of a broader, weirder Modernism to see it labeled only as "modernism" generally.)

Then there's Henry James. Not for the students, but the teachers:

As with Hemingway, James performed both an inner and an outer function for the discipline. In his prefaces and other essays, he established theories of modern fiction that legitimated its status as a discipline worthy of the university. Yet in his powers of parsing reality infinitesimally, James became an emblem similar to Hemingway, a practitioner of resolutely anti-Marxian fiction in an era starved for the same. (152)

Reducing the influence and appeal here to simply the anti-Marxian is a tic produced by Bennett's yearning for the return of the Popular Front, because his own evidence shows that the immense influence of Hemingway and James served not only to veer teachers, students, writers, and critics away from any whiff of agit-prop, but that it created an aesthetic not only hostile to Upton Sinclair but to the 19th century Decadents and Symbolists, to much of the Harlem Rennaissance, to most forms of popular literature, and to any writers who might seem too difficult, abstruse, or weird (imagine Samuel Beckett in a typical writing workshop!).

As Bennett makes clear, the

idea of Henry James's writing practice more than any of James's actual texts is what held through the decades. "He did at least five things for the discipline," Bennett says (152-153):

- His Prefaces assert the supremacy of the author, and "the early MFA programs depended above all on a faith that literary meaning could be stable and stabilized; that the author controlled the literary text, guaranteed its significance, and mastered the reader."

- James's approach was one of research and selection, which is highly appealing to research universities. Writing becomes a laboratory, the writer an experimenter who experiments succeed when the proper elements are selected and balanced. "He identified 'selection' as the major undertaking of the artist and perceived in the world a landscape without boundaries from which to do the selecting." Revision is key to the experiment, and revision should be limitless. Revision is virtue.

- James was anti-Romantic in a particular way: "James centered modern fiction on art rather than the artist, helping to shape the doctrines of impersonality so important to criticism from the 1920s through the 1950s. He insulated the aesthetic object from the deleterious encroachments of ego." Thus the object can be critiqued in the workshop, not the creator.

- "James nonetheless kept alive the romantic spirit of creative inspiration and drew a line between those who have it and those who don't." He often sounds mystical in his Prefaces (less so his Notebooks). The craft of writing can be taught, but the art of writing is the realm of genius.

- "James regarded writing as a profession and theorized it as one." The writer is someone who labors over material, and the integrity of the writer is equal to the integrity of the process, which leads to the integrity of the final text.

These ideas took hold and were replicated, passed down not only through workshops, but through numerous handbooks written for aspiring writers.

The effect, ultimately, Bennett asserts, was to stigmatize intellect. Writing must not be a process of thought, but a process of feeling. It must be sensory. "No ideas but in things!" A convenient ideology for times of political turmoil, certainly.

Semester after semester, handbook after handbook, professor after professor, the workshops were where, in the university, the senses were given pride of place, and this began as an ideological imperative. The emphasis on particularity, which remains ubiquitous today, inviolable as common sense, was a matter for debate as recently as 1935. The debate, in the 21st century, is largely over. (171)

I wonder. From writers and students I sense — and this is anecdotal, personal, sensory! — a desire for something more than the old Imagist ways. A desire for thought in fiction. For politics, but not a simple politics of vulgar Marxism. The ubiquity of dystopian fiction signals some of that, perhaps. Dystopian fiction is being written by both the hackiest of hacks and the highest of high lit folks. It shows a desire for imagination, but a particular sort of imagination: an imagination about society. Even at its most

personal, navel-gazing, comforting, and self-justifying, it's still at least trying to wrestle with more than the concrete, more than the story-iceberg.

So, too, the efflorescence of different types of writing programs and different types of teachers throughout the U.S. today suggests that the era of the aesthetic Bennett describes may be, if not over, at least far less hegemonic. Bennett cites its apex as somewhere around 1985, and that seems right to me. (I might bump it to 1988: the last full year of Reagan's presidency and the publication of Raymond Carver's selected stories,

Where I'm Calling From.) The people who graduated from the prestigious programs then went on to become the administrators later, but at this point most of them have retired or are close to retirement. There are still

narrow aesthetics, but there's plenty else going on. Most importantly, writers with quite different backgrounds from the old guard are becoming not just the teachers, but the administrators. Bennett notes that some of the criticism he received for

earlier versions of his ideas pointed to these changes:

I was especially convinced by the testimony of those who argued that the Iowa Writers' Workshop under Lan Samantha Chang's directorship has different from Frank Conroy's iteration of that program, which I attended in the late 1990s and whose atmosphere planted in my heart the suspicion that, for some reason, the field of artistic possibilities was being narrowed exactly where it should be broadest. In the twenty-first century, things have changed both at Iowa and at the many programs beyond Iowa, where few or none of my conclusions might have pertained in the first place. (163)

That's an important caveat there. The present is not the past, but the past contributed to the present, and it's a past that we're only now starting to recover.

There's much more to be investigated, as I'm sure Bennett knows. The role of the

Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and similar institutions would add some more detail to the study; similarly, I think someone needs to write about the intersections of creative writing programs and composition/rhetoric programs in the second half of the twentieth century. (Much more needs to be written about CUNY during

Mina Shaughnessy's time there, for instance, or about

Teachers & Writers.) But the value of Bennett's book is that it shows us that many of the ideas about what makes writing (and writers) "good" can be — should be — historicized. Such ideas aren't timeless and universal, and they didn't come from nowhere. Bennett provides a map to some of the wheres from whence they came.

Nation Books will publish an illustrated edition of the Travels With Henry James essay collection.

Nation Books will publish an illustrated edition of the Travels With Henry James essay collection.

According to the publisher’s announcement, Alessandra Bastagli, an editorial director, handled the acquisition of this project. This book will feature maps and paintings.

Michael Anesko, a scholar who studies Henry James’ (pictured, via) works, has signed on to write an introduction. Hendrik Hertzberg, a staff writer at The New Yorker, has agreed to write a foreword. Click on this link to download a digital copy of one of James’ most beloved travel books, Italian Hours.

I know Henry James is not everyone’s cup of tea but I love the long sentences, the way the story kind of oozes along, the psychological analysis, it’s good stuff! James was well aware what people thought of his stories. In the introduction to Portrait of a Lady he writes,

I’m often accused of no having ‘story’ enough. I seem to myself to have as much as I need — to show my people, to exhibit their relations with each other; for that is all my measure.

And that is what he does, examines relationships.

In Portrait of a Lady we have the young American Isabel Archer whose father has just died. Her two older sisters are married and Isabel is left with only a small income and no idea what to do with herself. He aunt swoops in from England and whisks her to Gardencourt where Isabel meets her uncle, Mr. Touchett and cousin Ralph. The Touchett’s are American expats who have more or less gone native, so to speak.

Isabel is naive and energetic, she wants to live life to its fullest on her own terms. She is without guile and so utterly charming that all the young men seem to fall in love with her. She left a suitor behind in America who eventually follows her to England in hopes of getting Isabel to marry him. Ralph’s friend and neighbor, Lord Warburton, is smitten and within days of meeting Isabel proposes. Isabel turns them all down because she is too well aware of the trap marriage will make for her.

Ralph loves Isabel too but keeps it to himself. Instead of asking her to marry him, when Mr. Touchett dies, Ralph asks that he settle a large part of his estate on Isabel. Ralph wants to see what kind of person and life Isabel will have when she has the money to do whatever she pleases.

At first it all goes well. But then Isabel falls into the clutches of Madame Merle who is nothing but gracious and perfect on the outside but a wicked schemer on the inside. Madame Merle sets up Isabel with Gilbert Osmond, an American expatriate living in Italy. He has a young daughter, Pansy, and a sad story of his wife’s death. He has no money but exquisite taste revealed in his collections of art and other items. Isabel is such a unique piece of work herself, plus she has money, so Osmond turns on the charm and adds Isabel to his collection by convincing her to marry him.

Of course it is not a happy marriage. Isabel refuses to properly fit into Osmond’s collection. There is much that happens with Isabel and Lord Warburton, with Pansy and her suitors, with Osmond and Madame Merle. Many times Isabel is offered the chance to escape her marriage but she refuses to leave out of sheer stubbornness and a belief that she made her bed and now she has to lie in it.

There are exciting secrets revealed. Marital arguments. Threats. For nothing happening there is quite a lot that happens! The ending is infuriatingly ambiguous. Isabel went to England against Osmond’s wishes to attend Ralph on his deathbed. Afterwards she returns to Italy but we are not sure if she returns to Osmond or if she returns to rescue Pansy from the convent Osmond has put her in as punishment.

Isabel is a frustrating character. She is independent and smart and speaks her mind. Yet she is always trying to be the good wife. She submits to Osmond as best she can, but her nature will only allow her to bend so far before she rebels. So she suffers both mentally and emotionally. It is well within her power to do something about it but she refuses. I wanted to yell at her. Ralph and Lord Warburton do. Well, they don’t yell, they are gentlemen after all, but they express their concern and strongly urge Isabel to leave. But the ending leaves us hanging. Will she go back to Osmond? I like to think she won’t but I don’t feel confident in that.

Isabel’s marriage is in direct comparison in many ways with the independent Henrietta Stackpole, feminist, journalist, and friend of Isabel. Henrietta and Ralph’s friend Mr. Bantling hit it off and begin traveling together. It is an entirely unconventional relationship but it works. Eventually Henrietta and Mr. Bantling get married but it is on Henrietta’s terms and we can believe that theirs will be a successful marriage. I loved Henrietta, she is what Isabel wanted to be (kind of) but couldn’t manage. The novel would be fun to reread some time and compare the two women and their marriages more carefully.

I read Portrait of a Lady along with Danielle. I liked it a lot more than she did but I think we both enjoyed it. It is one of James’s most popular long novels and if you are wanting to try Henry James and are a bit nervous about it, I think Portrait of a Lady is a good place to start.

Filed under:

Books,

Reviews Tagged:

Henry James

By: Stefanie,

on 7/1/2015

Blog:

So Many Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Emily Dickinson,

Elif Shafak,

Elizabeth Bishop,

John Keats,

Henry James,

In Progress,

Andy Weir,

Nuala O'Connor,

Add a tag

Can you believe it’s July already? I can’t. I was just getting used to June, just starting to feel like I was in the June groove, and now it’s time to move on. I am not ready. Can we turn the calendar back to June 15th please? That should be enough for me to get my fill of June and then when July 1st rolls around again I will be ready. Not going to happen you say? Where’s Marty McFly or the TARDIS when you need them?

Well, let’s barrel into July then. What will the month hold for reading? I get a 3-day holiday weekend coming up for Independence Day. Groovy, some extra reading time.

Even though I have been (mostly) good about keeping my library hold requests down to a manageable number, two books I have been looking forward to reading that have long waiting lines have, of course, both arrived for me at once. I now have to either a) rush through The Buried Giant and Get in Trouble in three weeks, or b) choose one to focus on and not worry about the other and get in line for it again if I run out of time. Choice “b” seems the most likely one I will go with which means Ishiguro’s Buried Giant will get my attention first. I am looking forward to it.

Carried over from last month, I am still reading Elif Shafak’s The Architect’s Apprentice. I am enjoying it much more than I was before even though I am making my way through it rather slowly.

In June I began reading Portrait of a Lady by Henry James and The Martian by Andy Weir. Two very different books and I am enjoying each of them quite a lot. James manages to be funny and ironic and ominous and can he ever write! I know people make fun of his long sentences but I get so involved in the reading I don’t even notice the length of the sentences. I do notice sometimes the paragraphs are very long, but that is only when I am nearing my train stop or the end of my lunch break and I am looking for a place to stop reading. And The Martian, is it ever a funny book. The book itself isn’t funny I guess, there is nothing very funny about being left for dead on Mars, the character, Mark Watney is funny; humor as survival tool. Weir, I must say, does a most excellent job of writing about complex science in such a way that is compelling and interesting and makes me feel smart.

I have a review copy of a new book called Miss Emily by Nuala O’Connor on its way to me. The Emily in question is Emily Dickinson. It’s a novel from Penguin Random House and they are kindly going to provide a second copy for a giveaway. Something to look forward to!

I will also begin reading Elizabeth Bishop this month. I’m still reading Keats letters and biography and poetry but he will get a bit less attention as I start to focus on Bishop. Much as I wanted to like Keats, it seems I like the idea of Keats more than the actuality; enjoy his letters more than his poetry. Not that his poetry isn’t very good, it is, at least some of it because there is quite a bit of mediocre stuff he wrote to/for friends that makes me wonder why I decided to read the collected rather than the selected. Hindsight and all that. But even the really good Keats poetry left me with mixed feelings. I mean, I appreciate it and sometimes I have a wow moment, but it generally doesn’t give me poetry stomach (the stomach flutters I get when I read a poem I really connect with). We’ll see how it goes with Bishop. I have her collected as well as her letters to work my way through over the coming months.

Without a doubt there will be other books that pop up through the month, there always are! The unexpected is all part of the fun.

Filed under:

Books,

In Progress Tagged:

Andy Weir,

Elif Shafak,

Elizabeth Bishop,

Emily Dickinson,

Henry James,

John Keats,

Nuala O'Connor

It’s 91F/33C out and I’m a bit wilty. It isn’t supposed to be this hot in June; the end of July it is allowed but not early June. But no one ever seems to care about my opinion.

I recently began reading Portrait of a Lady by Henry James along with Danielle. I’m really enjoying the book. Today, however, I am not going to talk about that. Instead I am going to reveal how silly it gets at my house sometimes.

Bookman asked me the other day what I was reading on my Kobo. I told him I had just started Portrait of a Lady.

That’s by James Joyce, right?

No, Henry James. I replied

Well didn’t James Joyce write something with portrait in the title?

Yes, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

And then things got goofy.

Bookman insisted that Henry James and James Joyce were actually the same person, after all, had anyone ever seen them at a party together? The true name of the man is Henry James Joyce.

Oh yes, I exclaimed and the real title of the book is Portrait of the Lady as a Young Man, it’s one of the first transgender novels ever written.

We’ve finally set the literary record straight, so to speak.

Our work here is done.

Filed under:

Books Tagged:

Henry James,

James Joyce

By: Hannah Paget,

on 5/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Arts & Humanities,

Byron's Letters and Journals,

Richard Lansdown,

Books,

Literature,

google,

google analytics,

jane austen,

Darwin,

Byron,

henry james,

Shelley,

keats,

george eliot,

Foucault,

literary figures,

*Featured,

Derrida,

Add a tag

Where would old literature professors be without energetic postgraduates? A recent human acquisition, working on the literary sociology of pulp science fiction, has introduced me to the intellectual equivalent of catnip: Google Ngrams. Anyone reading this blog must be tech-savvy by definition; you probably contrive Ngrams over your muesli. But for a woefully challenged person like myself they are the easiest way to waste an entire morning since God invented snooker.

The post Literary fates (according to Google) appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 4/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Victorian,

henry james,

Oxford World's Classics,

anthony trollope,

*Featured,

The Small House at Allington,

Arts & Humanities,

Barchester Towers,

Cornhill,

Fanny Hill,

John Bowen,

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure,

Miss Mackenzie,

Mr Frigidy,

Add a tag

Anthony Trollope. Safe, stodgy, hyper-Victorian Anthony Trollope, the comfort reading of the middle classes. As his rival and admirer Henry James said after his death 'With Trollope we were always safe’. But was he really the most respectable of Victorian novelists?

The post Anthony Trollope: not as safe as we thought he was? appeared first on OUPblog.

Fairy tale is a country of the mind where there are many inhabitants stretching back into deep time, and we're like people before Babel, we speak a common tongue: fairy tales exist in a symbolic Esperanto, with familiar motifs and images and characters and plots taking on new shapes and colors and sounds. One of [...]

You know how you have that friend you used to talk to on the phone all the time, every day practically, so that even though you lived hundreds of miles apart, you were totally up on all the daily details of each other’s lives? And then along comes a busy week, maybe two, and you play a few rounds of phone tag, and suddenly there’s SO MUCH to catch up on that you know you’re going to need an hour, probably more, who are we kidding, and so you’re both waiting for a nice long chunk of time and meanwhile more life is happening and you’re never ever going to be able to catch each other up on all of it? Yeah, that’s how I’m feeling about my book log today.

For a few weeks there I was trotting along at such a nice clip, recording everything—not only books finished, which I’ve been faithfully logging since 2008, but fragments and sections of books, history and science chapters read to the kids, picture books, substantive internet articles, even individual poems. I’ve never kept track of my reading to such a granular degree before, and I was really enjoying it—both as a chronicle of the many branchings of my interests, and as a somewhat, for me, revelatory indication of the sheer amount of reading, challenging and otherwise, that I was doing all along but somehow not “counting.” Sigh, I only read two books this month, I might think, looking a year from now at my GoodReads tally for April 2014, forgetting the quantities of poetry I devoured that month (just no complete books of poetry, so they don’t qualify for a GR entry), the hundred-odd pages of mid-19th century American history and 17th-century science my girls and I tackled together, the Scientific American articles, the half a novel that didn’t hold me, the five or six opening chapters I sampled on Kindle, the dozens of picture books enjoyed with my younger three, the lecture transcripts, the Damn Interesting articles, the AV Club reviews. Of course it all counts. It all goes to the shaping of me, the stretching of me. My old book log, the finished-books-only kind, presents a comically, unrecognizably skewed picture. Presents this skewed picture to me, I mean—I’m not supposing that anyone else is troubling themselves about it  —but future me will be much hazier about what riches were crammed in between those gaps in the record, the blank spaces between The Tuesday Club Murders and The Wheel on the School.

—but future me will be much hazier about what riches were crammed in between those gaps in the record, the blank spaces between The Tuesday Club Murders and The Wheel on the School.

I’ll want, you know, to remember how that April (this April) was the month of Donne and Herbert, and of The Secret Garden, and of The Little Fur Family and The Americans (the TV show, not the James novel) and Beginning Theory—how way led to way, and reading up on Donne turned into teaching a poetry class, and how things we were reading in The Story of Science kept cropping up on the new Cosmos the very next night, and vice versa.

Until I began the granular logging in March (was it March?), I hadn’t realized how much reading was happening in the margins. Then I missed a day, and the next day there was more to catch up on, and so on and so on, and there went April. All this to say I’m going to start over (again) and see how long I can keep it up this time—and if I miss a day, I’ll let it go, like a balloon floating away into the sky, and not lose hold of the next day’s balloon in an attempt to retrieve the first.

(But if I remember what color the lost balloons were, I can say so. I remember some of yesterday’s balloons.)

Yesterday I happened upon a long piece called “Selling Henry James,” a Northwestern University professor’s account (in 1990) of his experience teaching a James seminar to undergraduates one quarter. Very enjoyable read. I got there via a Jamesian rabbit trail, which branched off a Virginia Woolf rabbit trail, which started actually last fall (and now I can’t remember why; didn’t log it!) and was rediscovered—oh, gosh, I’m losing track of the meanderings. I’ve been watching these Milton lectures at Open Yale, and I think it may have been something the professor said in one of those that made me jump back to Woolf, and then to Gilbert and Gubar’s Madwoman in the Attic, which I’ve never read til now—it took me most of last week to get through the two introductions and the first chapter, but I don’t mean “get through” in a negative sense, it was fiercely interesting reading, and amusing in that I realized, a little way in, that this is the text which most deeply informed the women’s lit class I took in college, though Madwoman itself was never assigned. That was the fall of 1988, fourteen years after Madwoman was published, and our professor was in her first year of teaching. I’ve had fun fitting these pieces of the puzzle together.

Earlier this week, still on the Woolf trail, simultaneous with Madwoman, I landed on this site and read the “Women’s Images in Literature” lectures in their entirety. Mostly for review, but like everyone I have gaps. Came away with yet more books to cram into the impossible queue.

The picture book Huck keeps asking for this week, and which I don’t mind reading over and over—the art is so lush, the colors (deep blue and gold) unusual, and the story sweet—is The Bear’s Song, which I was so glad to see make it to our list of finalists in last year’s CYBILs contest.

Rilla and I are nearly finished with The Secret Garden. Mrs. Sowerby had to conspire to send the children more food today, they’re starving all the time. I don’t want it to end.

The girls and I are on to Robert Burns now, today was “To a Mouse.” I always do “To a Mouse.”

We’ve returned to our French songs—we forgot about them for a while—”Promenons Nous Dans le Bois” and “Les Éléphants” from the on the French for Kids: Cha Cha Cha CD, mostly. And a lot of Robert Burns songs on YouTube, and (for no particular reason) this rendition of Waltzing Matilda.

The Henry James article left me in a James mood (no, I suppose the mood was already creeping over me and that’s why I googled it?) so last night at bedtime I barraged my Kindle with his books, and this morning I fell into The Turn of the Screw, which I’ve never read (I’ve only read Portrait of a Lady, Daisy Miller, and Washington Square) and can’t wait for bedtime tonight so I can (try to) return to it. (The parentheses are because I’m still not managing nighttime reading, only crossword puzzles. Two nights ago I tried to read in bed. I remember nothing, but next morning when I opened the Kindle app on my phone, there was the E.M. Forster Collection open to his short story, “The Celestial Omnibus,” which I’d never read before. I fall asleep, and my finger hits the touchscreen, and I find surprises the next day, like this one. Forster was near the top of the library screen because of my binge in March. I read the Omnibus story and the next one, the one about the beech wood, “The Other Kingdom,” I think it’s called?, and then I had to go back and reread the last chapter of Howards End. (A part of me is always rereading the last chapter of Howards End.)

Before I end (with no conclusion), a James note and a James quote. The note is that, settling into (or being inexorably pulled into, I had no choice) Turn of the Screw and working, as one must, to keep up with the twistings of the sentences, I had this sudden rush of comfort—I don’t know how else to put it—of relief, really, in the realization that a thing about Henry James is that you can trust him to get you there in the end. To the end of the sentence, I mean. It’s going to have forty parts but in the end they will all hold together. I didn’t comprehend that the first time I read him, in my twenties. It’s like knowing a piece of music is going to resolve at the end of the phrase. The final chord will bring you back to the ground. Perhaps I’m a more patient reader now (now that I’m resigned to not getting through ALL THE BOOKS), or perhaps I’ve learned enough about craft over the years to know when a writer deserves my confidence. And I mean this observation only about syntax, about style—I don’t expect James to hand me the plot resolution I crave, he made that very clear at the start of our relationship (oh Isabel!)—but I find there’s an unlooked-for joy in trusting him on style.

And the quote: “Never say you know the last word about any human heart.”

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

oxford english dictionary,

henry james,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

oxfordwords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Jeff Sherwood,

very idiosyncrasy,

intersection between registers and,

phrase green,

and modernist,

its protagonist is,

Add a tag

By Jeff Sherwood

It is virtually impossible for an English-language lexicographer to ignore the long shadow cast by Henry James, that late nineteenth-century writer of fiction, criticism, and travelogues. We can attribute this in the first place to the sheer cosmopolitanism of his prose. James’s writing marks the point of intersection between registers and regions of English that we typically think of as mutually opposed: American and British, Victorian and modernist, intellectual and popular, even the simple good sense of Saxon-Germanicism and the fine silk shades of Franco-Romanticism. Thus, because his writing defies easy categories, it isn’t hard to suppose that James belongs in the back parlor of English-language history, a curiosity of passing interest, but one which, in its very idiosyncrasy, fails to capture the ‘ordinary, everyday’ language.

Henry James in the OED

Nevertheless, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites Henry James over one thousand times, often in entries for common English words like use, turn, come, do, and be. At least one explanation for this preponderance is the fact that, precisely because James’s prose incorporates elements from so many different kinds of English, it is uniquely positioned to exemplify—and even differentiate between—very subtle distinctions of usage and meaning. Thus, at green adj. James’s early novel The American provides a downright crystalline use of the phrase green in earth to mean ‘just buried’: ‘He thought of Valentin de Bellegarde, still green in the earth of his burial.’ By adding the final (semantically superfluous) three words, not only does James clarify the phrase’s context, he accentuates its poetic wordplay; its dependence on the double sense of green both as ‘new’ (sense 7a) and as ‘covered with vegetation’ (sense 2a) in order to conjure the renewal of the earth that is part and parcel of the burial rite. In this case, poeticism, often an obstacle to meaning, is actually the most probable explanation for the collocation’s longevity.

This old thing?

James’s ability to write prose that is both fastidiously discerning and euphemistically elliptical is not accidental, and cannot fail to intrigue someone whose business it is to describe words all day. In fact, despite clearly affectionate attachments to a number of words (presence and relation leap to mind), the one I would nominate as James’s absolute favorite is of great concern for lexicography—the thoroughly common word thing. Meaning quite literally any-thing from the genitals (sense 11 c) to a work of art (sense 13, complete with a James citation), thing is remarkably Jamesian in its ability to denote both the most concretely literal elements of reality and the most rarefied abstractions of human thought. And it is in just this respect that the word presents itself at the heart of perhaps the most naïve yet essential question that the lexicographer must answer: whether any particular meaning associated with a given word is actually ‘a thing.’ At times, this can be quite easy: it is not difficult to evaluate whether the physical object we mean when we say ‘smart phone’ is a ‘thing.’ But in many cases, the ‘thing’ referred to by a word is only conceptual. The existence of what we mean by ‘freedom’, for example, cannot be empirically proven. All we can say for sure is that the frequency and manner in which people use such words strongly suggests that they mean specific ‘things’.

Philosophically speaking, what makes ‘thing’ so interesting is that it straddles the gap between words that refer to physical objects and those that refer to abstract concepts, serving as a kind of verbal ‘junk drawer’ where items from both groups get casually tossed, only to wind up completely tangled and confused. Unsurprisingly, this confusion is just what James chooses to explore in his short story ‘The Real Thing.’ Its protagonist is an illustrator visited by two aristocrats, Major and Mrs. Monarch, who have fallen on hard times. They volunteer themselves as models for the artist, presuming that as bona fide members of society they are more suitable subjects for the aristocratic characters he depicts than the working-class types he typically employs. In fact, of course, the couple is awkward and unnatural, unable to embody the concept of aristocracy despite being literal examples of it.

Defining the tooth fairy

In just the same way, when a particular word is used ‘in the real world’, it will almost never be a perfect example of the concept it refers to. Consequently, it becomes the lexicographer’s job to improve upon ‘the real thing’, to illustrate a word more vividly than the real world can. This is especially clear when the word being defined refers to a fictional character, like the tooth fairy. To give wholesale priority to this term as a lexical object would render a definition like ‘a fairy that takes children’s baby teeth after they fall out and leaves a coin under the child’s pillow.’ This covers how the term is ordinarily used, since in everyday speech we are not in the habit of constantly remarking on the key conceptual detail that the tooth fairy is not real. Nevertheless, a definition that fails to note this misses, paradoxically enough, ‘the real thing.’ Just as Major Monarch doesn’t quite look like ‘the real thing’ he is, sometimes a word used in everyday speech doesn’t quite capture the thing it really is.

Jeff Sherwood is a US Assistant Editor for Oxford Dictionaries. Read more about Henry James with Oxford World’s Classics. A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

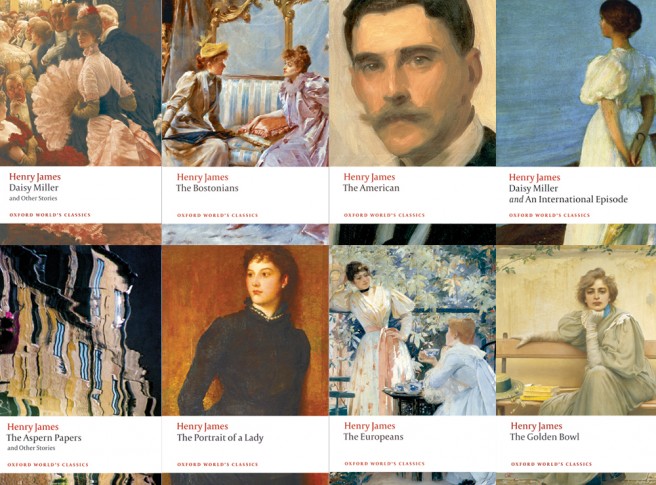

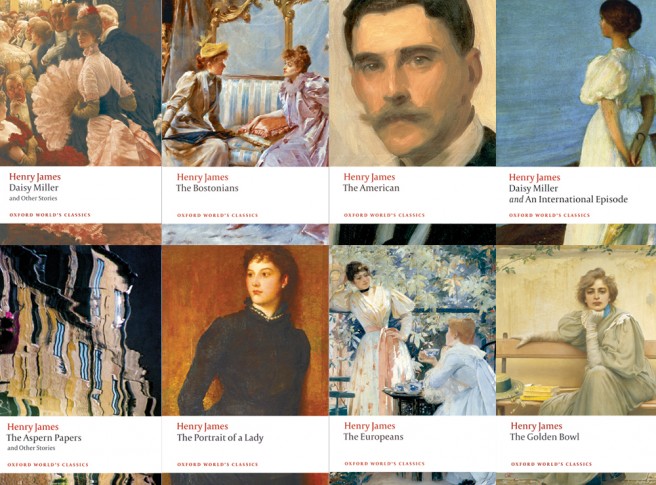

Image: Montage of Henry James Oxford World’s Classics editions.

The post Henry James, or, on the business of being a thing appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

classic,

joyce,

William Carlos Williams,

OWC,

modernism,

Tom Stoppard,

henry james,

Oxford World's Classics,

Gertrude Stein,

Robert Lowell,

ezra pound,

Ernest Hemingway,

first world war,

Joseph Conrad,

Humanities,

Jean Rhys,

Theodore Dreiser,

Benedict Cumberbatch,

*Featured,

Stephen Crane,

TV & Film,

Susanna White,

Arts & Leisure,

e. e. cummings,

Ford Madox Ford,

Good Soldier,

Max Saunders,

Parade’s End,

A Dual Life,

British novel,

Christopher Tietjens,

D. H. Lawrence,

Rebecca Hall,

Stella Bowen,

Valentine Wannop,

Wyndham Lewis,

Add a tag

By Max Saunders

One definition of a classic book is a work which inspires repeated metamorphoses. Romeo and Juliet, Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Great Gatsby don’t just wait in their original forms to be watched or read, but continually migrate from one medium to another: painting, opera, melodrama, dramatization, film, comic-strip. New technologies inspire further reincarnations. Sometimes it’s a matter of transferring a version from one medium to another — audio recordings to digital files, say. More often, different technologies and different markets encourage new realisations: Hitchcock’s Psycho re-shot in colour; French or German films remade for American audiences; widescreen or 3D remakes of classic movies or stories.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Ford served in the First World War, getting injured and suffering from shell shock in the Battle of the Somme. He moved to France after the war, where he soon joined forces with Pound again, to form another influential modernist magazine, the transatlantic review, which published Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Jean Rhys. Ford took on another young American, Ernest Hemingway, as his sub-editor. Ford held regular soirees, either in a working class dance-hall with a bar that he’d commandeered, or in the studio he lived in with his partner, the Australian painter Stella Bowen. He found himself at the centre of the (largely American) expatriate artist community in the Paris of the 20s. And it was there, and in Provence in the winters, and partly in New York, that he wrote the four novels of Parade’s End, that made him a celebrity in the US. He spent an increasing amount of time in the US through the 20s and 30s, based on Fifth Avenue in New York, becoming a writer in residence in the small liberal arts Olivet College in Michigan, spending time with writer-friends like Theodore Dreiser and William Carlos Williams, and among the younger generation, Robert Lowell and e. e. cummings.

Parade’s End (1924-28) has been dramatized for TV by Sir Tom Stoppard. It has to be one of the most challenging books to film; but Stoppard has the theatrical ingenuity, and experience, to bring it off. It’s a classic work of Modernism: with a non-linear time-scheme that can jump around in disconcerting ways; dense experimental writing that plays with styles and techniques. Though it includes some of the most brilliant conversations in the British novel, and its characters have a strong dramatic presence, much of it is inherently un-dramatic and, you might have thought, unfilmable: long interior monologues, descriptions of what characters see and feel; and — perhaps hardest of all to convey in drama — moments when they don’t say what they feel, or do what we might expect of them. Imagine T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, populated by Chekhovian characters, but set on the Western Front.

I’ve worked on Ford for some years, yet still find him engaging, tantalising, often incomprehensibly rewarding, so I was watching Parade’s End with fascination. [Warning: Spoilers ahead.]

Click here to view the embedded video.

Stoppard and the director, Susanna White, have done an extraordinary job in transforming this rich and complex text into a dramatic line that is at once lucid and moving. Sometimes where Ford just mentions an event in passing, the adaptation dramatizes the scene for us. The protagonist is Christopher Tietjens, a man of high-Tory principle — a paradoxical mix of extreme formality and unconventional intelligence – is played outstandingly by Benedict Cumberbatch, with a rare gift to convey thought behind Tietjens’ taciturn exterior. In the novel’s backstory, Christopher has been seduced in a railway carriage by Sylvia, who thinks she’s pregnant by another man. The TV version adds a conversation as they meet in the train; then cuts rapidly to a sex scene. It’s more than just a hook for viewers unconcerned about textual fidelity, though. What it establishes is what Ford only hints at through the novel, and what would be missed without Tietjen’s brooding thoughts about Sylvia: that her outrageousness turns him on as much as it torments him. In another example, where the novelist can describe the gossip circulating like wildfire in this select upper-class social world, the dramatist needs to give it a location; so Stoppard invents a scene at an Eton cricket match for several of the characters to meet, and insult Valentine Wannop, while she and Tietjens are trying not to have the affair that everyone assumes they are already having. Valentine is an ardent suffragette. In the novel, she and Tietjens argue about women and politics and education. Stoppard introduces a real historical event from the period — a Suffragette slashing Velasquez’s ‘Rokeby Venus’ in the National Gallery — as a way of saying it visually; and then complicating it beautifully with another intensely visual interpolated moment. In the book Ford has Valentine unconcsciously rearranging the cushions on her sofa as she waits to see Tietjens the evening before he’s posted back to the war. When she becomes aware that she’s fiddling with the cushions because she’s anticipating a love-scene with him, the adaptation disconcertingly places Valentine nude on her sofa in the same position as the ‘Rokeby Venus’ — in a flash both sexualizing her politics and politicizing her sexuality.

Such changes cause a double-take in viewers who know the novels. But they’re never gratuitous, and always respond to something genuine in the writing.

Perhaps the most striking transformation comes during one of the most amazing moments in the second volume, No More Parades. Tietjens is back in France, stationed at a Base Camp in Rouen, struggling against the military bureaucracy to get drafts of troops ready to be sent to the Front Line. Sylvia, who can’t help loving Tietjens though he drives her mad, has somehow managed to get across the Channel and pursue him to his Regiment. She has been unfaithful, and he is determined not to sleep with her; but because his principles won’t let a man divorce a woman, he feels obliged to share her hotel room so as not to humiliate her publicly. She is determined to seduce him once more; but has been flirting with other officers in the hotel, two of whom also end up in their bedroom in a drunken brawl. It’s an extraordinary moment of frustration, hysteria, terror (there has been a bombardment that evening), confusion, and farce. In the book we sense Sylvia’s seductive power, and that Tietjens isn’t immune to it, even though by then in love with Valentine. He resists. But in the film version, they kiss passionately before being interrupted.

Valentine and Christopher. Adelaide Clemens and Benedict Cumberbatch in Parade’s End. (c) BBC/HBO.

The scene may have been changed to emphasize the power she still has over Tietjens: as if, paradoxically, he needs to be seen to succumb for a moment to make his resistance to her the more heroic. The change that’s going to exercise enthusiasts of the novels, though, is the way three of the five episodes were devoted to the first novel, Some Do Not…; and roughly one each to the second and third; with very little of the fourth volume, Last Post, being included at all. The third volume, A Man Could Stand Up — ends where the adaptation does, with Christopher and Valentine finally being united on Armistice night, a suitably dramatic and symbolic as well as romantic climax. Last Post is set in the 1920s and deals with post-war reconstruction. One can see why it would have been the hardest to film: much of it is interior monologue, and though Tietjens is often the subject of it he is absent for most of the book. Some crucial scenes from the action of the earlier books is only supplied as characters remember them in Last Post, such as when Syliva turns up after the Armistice night party lying to Christopher and Valentine that she has cancer in an attempt to frustrate their union. Stoppard incorporates this into the last episode, but he writes new dialogue for it to give it a kind of closure the novels studiedly resist. Valentine challenges her as a liar, and from Tietjens’ reaction, Sylvia appears to recognize the reality of his love for her and gives her their blessing.

Rebecca Hall, playing Sylvia, has been so brilliantly and scathingly sarcastic all the way through that this change of heart — moving though it is — might seem out of character: even the character the film gives her, which is arguably more sympathetic than the one most readers find in the novel. Yet her reversal is in Last Post. But what triggers it there, much later on, is when she confronts Valentine but finds her pregnant. Even the genius of Tom Stoppard couldn’t make that happen before Valentine and Christopher have been able to make love. But there are two other factors, which he was able to shift from the post-war time of Last Post into the war’s endgame of the last episode. One is that Sylvia has focused her plotting on a new object. Refusing the role of the abandoned wife of Tietjens, she has now set her sights on General Campion, and begun scheming to get him made Viceroy of India. The other is that she feels she has already dealt Tietjens a devastating blow, in getting the ‘Great Tree’ at his ancestral stately home of Groby cut down. In the book she does this after the war by encouraging the American who’s leasing it to get it felled. In the film she’s done it before the Armistice; she’s at Groby; Tietjens visits there; has a Stoppard scene with Sylvia arranged in her bed like a Pre-Raphaelite vision in a last attempt to re-seduce him, which fails partly because of his anger over the tree. In the books the Great Tree represents the Tietjens family, continuity, even history itself. Ford writes a sentence about how the villagers “would ask permission to hang rags and things from the boughs,” but Stoppard and White make that image of the tree, all decorated with trinkets and charms, a much more prominent motif, returning to it throughout the series, and turning it into a symbol of superstition and magic. But then Stoppard characteristically plays on the motif, and has Christopher take a couple of blocks of wood from the felled tree back to London. One he gives to his brother, in a wonderfully tangible and taciturn gesture of renouncing the whole estate and the history it stands for. The other he uses in his flat, throwing whisky over it in the fireplace to light a fire to keep himself and Valentine warm. That gesture shows how it isn’t just Sylvia who is saying ‘Goodbye to All That’, but all the major characters are anticipating the life that, though the series doesn’t show it, Ford presents in the beautifully elegiac Last Post.

Max Saunders is author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life (OUP, 1996/2012), and editor of Some Do Not . . ., the first volume of Ford’s Parade’s End (Manchester: Carcanet, 2010) and Ford’s The Good Soldier (Oxford: OUP, 2012). He was interviewed by Alan Yentob for the Culture Show’s ‘Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford’ (BBC 2; 1 September 2012), and his blog on Ford’s life and work can be read on the OUPblog and New Statesman.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of Ford Madox Ford (Source: Wikimedia Commons); (2) Still from BBC2 adaption of Parade’s End. (Source: bbc.co.uk).

The post Ford Madox Ford and unfilmable Modernism appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Maryann Yin,

on 10/3/2012

Blog:

Galley Cat (Mediabistro)

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Henry James,

Christopher Pike,

Ginger Clark,

Writer Resources,

Gretchen McNeil,

Diane Setterfield,

Daphne DuMaurier,

Kristin Daly Rens,

William Peter Blatty,

Young Adult Books,

Authors,

horror,

Edgar Allen Poe,

Add a tag

Happy October! In honor of the Halloween season, we’ll be interviewing horror writers to learn about the craft of scaring readers. Recently, we spoke with young adult novelist Gretchen McNeil.

Happy October! In honor of the Halloween season, we’ll be interviewing horror writers to learn about the craft of scaring readers. Recently, we spoke with young adult novelist Gretchen McNeil.

In September, HarperCollins Children’s Books published McNeil’s latest novel. When Barnes & Noble decided not to carry this title in their stores, she launched an internet marketing campaign called the “Army of TEN” and offered incentives for readers who helped to promote the book.

Currently, this title holds the #88 spot on Amazon’s list of bestselling teen books in the “mysteries” category. Check out the highlights from our interview below…

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Alice,

on 9/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Ford Madox Ford,

Good Soldier,

Max Saunders,

Parade’s End,

Literature,

modernism,

henry james,

Ernest Hemingway,

Impressionism,

first world war,

Graham Greene,

Humanities,

Jean Rhys,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Max Saunders

This year’s television adaptation of Parade’s End has led to an extraordinary surge of interest in Ford Madox Ford. The ingenious adaptation by Sir Tom Stoppard; the stellar cast, including Benedict Cumberbatch, Rebecca Hall, Alan Howard, Rupert Everett, Miranda Richardson, Roger Allam; the flawlessly intelligent direction by award-winning Susanna White, have not only created a critical success, but reached Ford’s widest audience for perhaps fifty years. BBC2 drama doubled its share of the viewing figures. Reviewers have repeatedly described Parade’s End as a masterpiece and Ford as a neglected Modernist master. Those involved in the production found him a ‘revelation’, and White and Hall are reported as saying that they were embarrassed that their Oxbridge educations had left them unaware of Ford’s work. After this autumn, fewer people interested in literature and modernism and the First World War are likely to ask the question posed by the title of Alan Yentob’s ‘Culture Show’ investigation into Ford’s life and work on September 1st: “Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford?”

Sylvia and Christopher Tietjens, played by Rebecca Hall and Benedict Cumberbatch in the BBC2 adaptation of Parade's End.

It’s a good question, though. Ford has to be one of the most mercurial, protean figures in literary history, capable of producing violent reactions of love, admiration, ridicule or anger in those who knew him, and also in those who read him. Many of those who knew him were themselves writers — often writers he’d helped, which made some (like Graham Greene) grateful, and others (like Hemingway) resentful, and some (like Jean Rhys) both. So they all felt the need to write about him — whether in their memoirs, or by including Fordian characters in their fiction. Ford himself thought that Henry James had based a character on him when young (Merton Densher in The Wings of the Dove). Joseph Conrad too, who collaborated with Ford for a decade, is thought to have based several characters and traits on him.

I’d spent several years trying to work out an answer that satisfied me to the question of who on earth Ford was. The earlier, fairly factual biographies by Douglas Goldring and Frank MacShane had been supplanted by more psycho-analytic studies by Arthur Mizener and Thomas C. Moser. Mizener took the subtitle of Ford’s best-known novel, The Good Soldier, as the title of his biography: The Saddest Story. He presented Ford as a damaged psyche whose fiction-writing stemmed from a sad inability to face the realities of his own nature. Of course all fiction has an autobiographical dimension. A novelist’s best way of understanding characters is to look into his or her own self. But there is an element of absurdity in diagnosing an author’s obtuseness from the problems of fictional characters. This is because if writers can make us see what’s wrong with their characters, that means they understand not only those characters, but themselves (or at least the traits they share with those characters). John Dowell, the narrator of The Good Soldier, appears at times hopelessly inept at understanding his predicament. His friend, the good soldier of the title, Edward Ashburnham, is a hopeless philanderer. If Ford saw elements of himself in both types, he had to be more knowing than them in order to show them to us. And anyway, they’re diametrically opposed as types.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Compared to some of the canonical modernists like Joyce or Eliot, Ford is unusual in writing so much about his own life — a whole series of books of reminiscences. They’re full of marvelous stories. Take the one with which he ends his book celebrating Provence. He describes how, when he earned a sum of money during the Depression, he and Janice Biala decided it was safer to cash it all rather than trust to failing banks. They visit one of Ford’s favourite towns, Tarascon on the Rhone. Ford has entrusted the banknotes to Biala. “I am constitutionally incapable of not losing money,” said Ford. But as they cross the bridge, the legendary mistral starts blowing:

And leaning back on the wind as if on an upended couch I clutched my béret and roared with laughter… We were just under the great wall that keeps out the intolerably swift Rhone… Our treasurer’s cap was flying in the air… Over, into the Rhone… What glorious fun… The mistral sure is the wine of life… Our treasurer’s wallet was flying from under an armpit beyond reach of a clutching hand… Incredible humour; unparalleled buffoonery of a wind… The air was full of little, capricious squares, floating black against the light over the river… Like a swarm of bees: thick… Good fellows, bees….

And then began a delirious, panicked search… For notes, for passports, for first citizenship papers that were halfway to Marseilles before it ended… An endless search… With still the feeling that one was rich… Very rich.

“I hadn’t been going to do any writing for a year,” mused Ford, recognising what an unlikely prospect it was. “But perhaps the remorseless Destiny of Provence desires thus to afflict the world with my books….” Yet for all the wry cynicism of this afterthought Biala remembered that “Ford was amused for months at the thought that some astonished housewife cleaning fish might have found a thousand-franc note in its belly.”

Ford’s stories, for all their playfulness, also earned him notoriety for the liberties they took with the facts. Indeed, Ford courted such controversy, writing in the preface to the first of them, Ancient Lights, in 1911:

This book, in short, is full of inaccuracies as to facts, but its accuracy as to impressions is absolute [....] I don’t really deal in facts, I have for facts a most profound contempt. I try to give you what I see to be the spirit of an age, of a town, of a movement. This can not be done with facts. (pp. xv-xvi)

He called his method Impressionism: an attention to what happens to the mind when it perceives the world. Ford is the most important analyst in English of Impressionism in literature, not only elaborating the techniques involved, but defining a movement. This included writers he admired like Flaubert, Maupassant and Turgenev, as well as his friends James, Conrad, and Crane. He also used the term to cover writers we now think of as Modernist, such as Rhys, Hemingway, or Joyce. Though most of these writers were resistant to the label, they wrote much about ‘impressions’ and their aesthetic aims have strong family resemblances.

One feature that sets Ford’s writing apart is his tendency to retell the same stories, but with continual variations. This creates an immediate problem for a literary biographer wanting to use the subject’s autobiographical writing to structure the narrative upon. Which version to use? Which to believe? They can’t all be true. And their sheer proliferation and multiplicity shows how he couldn’t tell a story about himself without it turning into a kind of fiction. In one particularly striking example, which Ford tells at least five times, he is taking the train with Conrad to London to take to their publisher corrected proofs of their major collaborative novel, Romance. Conrad is obsessively still making revisions, and because he’s distracted by the jolting of the train, he lies down on his stomach so he can correct the pages on the floor. As the train pulls into their London station, Ford taps Conrad on the shoulder. But Conrad is so immersed in the world of Cuban pirates, says Ford, that he springs up and grabs Ford by the throat. Ford’s details often seem too exaggerated for some readers. Would Conrad really have gone for his friend like that? Would he really have hazarded his city clothes on a train carriage floor? The fact that the details change from version to version shows how fluid they are to Ford’s imagination, but there’s at least a grain of plausible truth. Here it’s the power of literature to engross its readers, so that one could be genuinely startled when interrupted while reading minutely. So, as with many of Ford’s stories, it’s a story about writing, writers, and what Conrad called “the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel… before all, to make you see.” And perhaps one of the things Ford wants us to see in this episode is how any aggression between friends who are writers needs to be understood in that context — as motivated as much by their obsession with words, as by any personal hostilities.

That is why a writer’s life — especially the life of a writer like Ford — is a dual one. As many of them have observed, writers live simultaneously in two worlds: the social world around them, and world they are constantly constructing in their imaginations. Impressionism seemed to Ford the method that best expressed this:

I suppose that Impressionism exists to render those queer effects of real life that are like so many views seen through bright glass — through glass so bright that whilst you perceive through it a landscape or a backyard, you are aware that, on its surface, it reflects a face of a person behind you. For the whole of life is really like that; we are almost always in one place with our minds somewhere quite other.

Ford’s life was dual in another important way, though. Like many participants, he felt the First World War as an earthquake fissure between his pre-war and post-war lives. It divided his adult life into two. His decision to change his name (after the war, which he had endured with a German surname), and to change it to its curiously doubled final form, surely expresses that sense of duality. Ford was in his early forties when he volunteered for the Army — something he could easily have avoided on account not only of his age, but of the propaganda writing he was doing for the Government. His experience of concussion and shell-shock after the Battle of the Somme changed him utterly, and provided the basis for his best work afterwards. Though he wrote over eighty books, most of them with brilliance and insight, two masterpieces have stood out: The Good Soldier, which seems the culmination of his pre-war life and apprenticeship to the craft of fiction, and then the Parade’s End sequence of four novels, which drew on his own war experiences to produce one of the great fictions about the First World War, or indeed any war.