The Linguistics Society of America’s Annual Conference will take place from Thursday, 8 January-Sunday, 11 January at the Hilton Portland & Executive Tower in Portland, Oregon. This meeting will bring together linguists from all over the world for a weekend filled with presentations, films, mini-courses, panels, and more.

If you’re looking for fun places to check out in Portland before and/or after the conference, look no further. In order to get the scoop on the best places to check out in Portland, I checked in with our resident Portland expert Jenny Catchings, the newest addition to our Academic/Trade Marketing Team. Before she moved to New York, Jenny lived in Portland for three years, and she’s ready to share a local’s guide to the “The City of Roses.”

-

Best Part about the PDX Airport: the carpet.

Believe it or not, the carpet at the airport enjoys a tremendous amount of love and fame. It even has its own Facebook fan page! (DSC01384 PDX Airport Carpet by Adam Dachis. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Coffee: Coava Coffee.

Coffee that will make you nervous to order… Coava fully embraces the intimidating Coffee Dork culture. (Coava Machiatto by Potjie. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Breakfast Place: Juniors Café.

Sparkle booths, mismatched cups, almost never featuring one of those epic brunch lines as mocked in Portlandia. (Junior’s Café by VJ Beauchamp. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Bookstore: Powell's Books.

In Portland, the book game is run by Powell’s. You walk in and it’s kind of like a museum — you could spend the whole day in there. There are lots of readings, even by big name authors, so you really get the full bookstore experience. Fun fact: There are a few smaller branches in SE Portland which are more specialized and low-key, if you’re looking for that teeny, indie-bookstore vibe. (Powell’s City of Books by Kenn Wilson. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Museum: Portland Art Museum.

Like many Northwestern art museums, The Portland Art Museum tends to feature indigenous art work, which is really beautiful. There are also a lot of local artists on display. (Portland Art Museum by Roger. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Doughnuts: Blue Star Donuts.

Portland does doughnuts exceptionally well. Everyone knows about Voodoo Doughnuts (and their legendary NyQuil doughnut), but locals prefer less gimmicky stuff. The thought of fresh Blue Star treats makes me homesick. Note: there are three locations ‘round the city. (Blue Star Donuts by Rick Chung. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Vintage Shopping: Lounge Lizard.

Lounge Lizard is this very curated, very beautiful house filled with mid-century housewares and gorgeous antiques. Best part? It’s pretty affordable! (Lounge Lizard, SE Hawthorne Portland, Or by Mike Krzeszak. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

-

Best Park: Laurelhurst Park.

It’s gigantic. It’s the kind of place where people go and hang out all day. It’s a great place to go if you want to meet the locals… people from Portland are very friendly! (Laurelhurst Park, Portland, Oregon, 2014 by Where Is Your Toothbrush? CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Ice Cream Spot: Salt and Straw.

Salt and Straw creates some really beautiful, often seasonal flavors. Some of the flavors may sound strange, but trust me, they always work. Their biggest hit is the ‘Strawberry Honey Balsamic with Black Pepper’ flavor. (Salt & Straw by jpellgen. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Music Venue: The Doug Fir.

Small and fun shows, looks like a log cabin inside, and sweet martinis in the bar. (Doug Fir Lounge — Portland, OR by Beyond Neon. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Tapas/Dinner Restaurant: Biwa.

My favorite dinner restaurant: Biwa. It’s small and very romantic. Don’t forget the sake! (Yakimoni at Biwa by VJ Beauchamp. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

Best Bar in a House: Liberty Glass.

Liberty Glass is literally a house in NE Portland, a big pink one at that. Portland used to have a few of these types of establishments, but this is one of the last ones standing now. You can sit in the ‘living room,’ upstairs in what used to be bedrooms or on the awesome porch when the weather is fine. (8:36pm: a drink at the Liberty Glass with Tom by Liene Verzemnieks. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.)

-

It’s going to be a great weekend in Portland and we can’t wait to see you there — be sure to come visit us at the Oxford University Press Booth (#3) in the Exhibit Hall!

Featured image: “Point Me At The Sky” by Ian Sane. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Exploring the best of Portland, Oregon during LSA 2015 Conference appeared first on OUPblog.

By Tim Allen

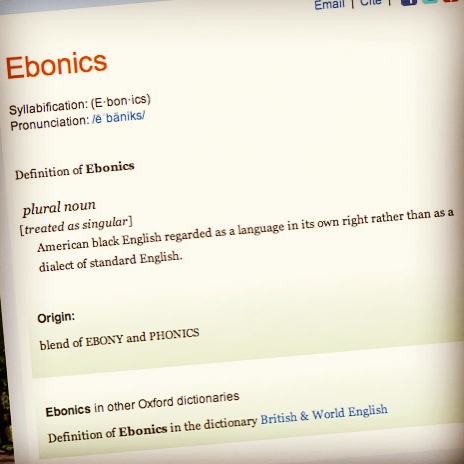

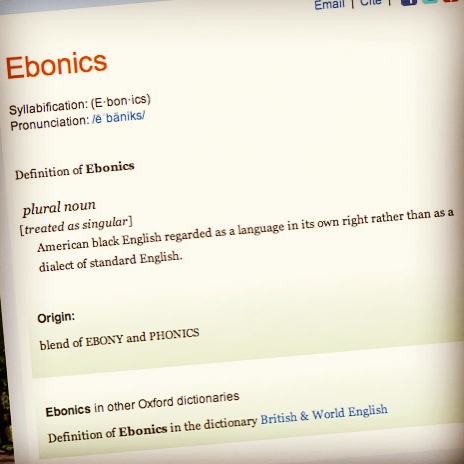

On this day forty years ago, the African American psychologist Robert Williams coined the term “Ebonics” during an education conference held at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. At the time, his audience was receptive to, even enthusiastic about, the word. But invoke the word “Ebonics” today and you’ll have no trouble raising the hackles of educators, journalists, linguists, and anyone else who might have an opinion about how people speak. (That basically accounts for all of us, right?) The meaning of the controversial term, however, has never been entirely stable.

For Williams, Ebonics encompassed not only the language of African Americans, but also their social and cultural histories. Williams fashioned the word “Ebonics”—a portmanteau of the words “ebony” (black) and “phonics” (sounds)—in order to address a perceived lack of understanding of the shared linguistic heritage of those who are descended from African slaves, whether in North America, the Caribbean, or Africa. Williams and several other scholars in attendance at the 1973 conference felt that the then-prevalent term “Black English” was insufficient to describe the totality of this legacy.

Ebonics managed to stay under the radar for the next couple of decades, but then re-emerged at the center of a national controversy surrounding linguistic, cultural, and racial diversity in late 1996. At that time, the Oakland, California school board, in an attempt to address some of the challenges of effectively teaching standard American English to African American schoolchildren, passed a resolution recognizing the utility of Ebonics in the classroom. The resolution suggested that teachers should acknowledge the legitimacy of the language that their students actually spoke and use it as a sort of tool in Standard English instruction. Many critics understood this idea as a lowering of standards and an endorsement of “slang”, but the proposed use of Ebonics in the classroom did not strike most linguists or educators as particularly troublesome. However, the resolution also initially characterized Ebonics as a language nearly entirely separate from English. (For example, the primary advocate of this theory, Ernie Smith, has called Ebonics “an antonym for Black English.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 21)) The divisive idea that “Ebonics” could be considered its own language—not an English dialect but more closely related to West African languages—rubbed many people the wrong way and gave a number of detractors additional fodder for their derision.

Linguists were quick to respond to the controversy and offer their own understanding of “Ebonics”. In the midst of the Oakland debate, the Linguistic Society of America resolved that Ebonics is a speech variety that is “systematic and rule-governed like all natural speech varieties. […] Characterizations of Ebonics as “slang,” “mutant,” ” lazy,” “defective,” “ungrammatical,” or “broken English” are incorrect and demeaning.” The linguists refused to make a pronouncement on the status of Ebonics as either a language or dialect, stating that the distinction was largely a political or social one. However, most linguists agree on the notion that the linguistic features described by “Ebonics” compose a dialect of English that they would more likely call “African American Vernacular English” (AAVE) or perhaps “Black English Vernacular”. This dialect is one among many American English dialects, including Chicano English, Southern English, and New England English.

And if the meaning of “Ebonics” weren’t muddy enough, a fourth perspective on the term emerged around the time of the Oakland debate. Developed by Professor Carol Aisha Blackshire-Belay, this idea takes the original view of Ebonics as a descriptive term for languages spoken by the descendants of West African slaves and expands it to cover the language of anyone from Africa or in the African diaspora. Her Afrocentric vision of Ebonics, in linguist John Baugh’s estimation, “elevates racial unity, but it does so at the expense of linguistic accuracy.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 23)

The term “Ebonics” seems to have fallen out of favor recently, perhaps due to the unpleasant associations with racially-tinged debate that it engenders (not to mention the confusing multitude of definitions it has produced!). However, the legacy of the Ebonics controversy that erupted in the United States in 1996 and 1997 has been analyzed extensively by scholars of language, politics, and race in subsequent years. And while “Ebonics”, the word, may have a reduced presence in our collective vocabulary, many of the larger issues surrounding its controversial history are still with us: How do we improve the academic achievement of African American children? How can we best teach English in school? How do we understand African American linguistic heritage in the context of American culture? Answers to these questions may not be immediately forthcoming, but we can, perhaps, thank “Ebonics” for moving the national conversation forward.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Ebonics’ in flux appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anatoly Liberman

The British journals of the Victorian era are an inexhaustible source of elegant phrases, which arouse in me sometimes envy and sometimes amused wonderment. Therefore, while remaining true to that style, I will say that I follow the comments sent to this blog “with appreciative interest, leavened in some cases by knowledge” (a gem from an 1889 article).

Three linguists called geniuses. My innocent conclusion to the post on the origin of the words sea and ocean called forth a few humorous remarks. I said that, in my opinion, Jacob Grimm (1785-1853) was a genius, one of three linguists who deserved such an honor. So who are the other two? It is like the famous question about three common English words ending in -ry: the first two are angry and hungry—what’s the third? (Answer: The third does not exist; the question is a hoax.) But I really meant three. After Grimm came the Swiss Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), who, at the age of 21 (at this age, our undergraduates still need a spellchecker to tell them how to write a lot: one word or two?), offered a reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European vowel system that changed Indo-European studies forever. Later he gave a series of lectures on general linguistics at the University of Geneva. After his death, his students, who had made copious notes (as students should), brought them out in book form. Since their publication, general linguistics and, to a certain extent, all the humanities have never been the same. Finally, N.S. Trubetzkoy (1890-1938), a Russian émigré, who taught most of the time he spent in the West at Vienna University, founded a branch of linguistics called phonology. His achievement influenced the development of 20th-century humanities almost as strongly as de Saussure’s. Close to those three are the German Eduard Sievers (1850-1932) and Trubetzkoy’s friend and collaborator Roman Jakobson (1896-1982). Jakobson also emigrated from Russia after the 1917 revolution, and following the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia, where he lived, fled to Sweden and a short time later to the United States. This is my ranking of the greatest greats. I left out Jean F. Champollion (1790-1832), who deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics. He was certainly a genius, but not exactly a linguist in the modern sense of the word. Neither among the dead nor among the living can I find anyone approaching those three or five, but as I said in the post, linguistics is unlike music or mathematics, and the contours of genius there are blurry. Other nominations to this Hall (Club) of Fame are welcome.

No questions left behind? It depends. A journalism student sent me a series of questions (eight, to be precise) about the power of words, their change, and so on. She also explained that the answers were needed for a paper (she is not generic: there was a signature). I am accosted along these lines all the time, and I am sorry to inform the questioners that I refuse to write papers for students. I believe they should do their research themselves, and also I am afraid of disgracing myself. Rachmaninoff helped his niece (I think it was a niece) to harmonize a short piece for her studies at the Conservatory. The assignment received a C, the only time Rachmaninoff got a grade below an A or A+. He was tickled to death by the result, but I am touchy and do not want to get either the poor girl or myself into trouble.

Generic they/their. No one has asked me anything about this pronoun in recent weeks, but I have two examples in my archive that I find particularly silly. I think I have once quoted the first of them; however, a good joke bears repetition. “As someone who has been pro-life all their life, I believe life begins at the point of conception…” In principle, their with someone is fine, but the syntax is muddled, and the writer (this time a male) seems to have been stultified to the point at which “they” don’t dare use even the pronoun his and my about “themselves.” The second quotation stresses the importance of knowing everything about one’s bedfellows: “If your friend told you they were going to have sex with someone they ‘knew pretty well,’ you’d probably tell them to be careful.” Very reasonable. Always make it clear to those you sleep with on any occasion how wide-awake you are. The advice comes from the student paper of my university, which is predominantly interested in peace, sports, diversity, and condoms.

The change of er to ar in English and French. The change of er to ar in early Modern English is well-known, and I have touched on it in the past while answering a question from one of our correspondents. The anthologized examples are person ~ parson, university ~ varsity, clerk ~ Clark, Derby ~ Darby, and their likes. I even proposed a tentative explanation of the change. During the time Engl. er, ir, and ur merged into the vowel we now hear in fern, fir, and fur, in some words the group er, as I suggested, escaped the merger by going over to ar (hence parson, and so forth). Such movements regularly occur in phonetic systems. But the weak point of such explanations is that identical changes have been recorded in dissimilar languages. The question from our correspondent concerned the French family name Vardun. Assuming that it goes back to the place name Verdun (and there can probably be no doubt about it), are we justified in reconstructing the change of er to ar in French? The answer is yes. As early as the 13th century, rhymes of the sarge (the name of the fabric serge)/ large type and spellings like sarpent (= serpent) occur. Villon (the middle of the 15th century) rhymed terme and arme, among others. French historical linguists tend to account for the broadening of er to ar by the altered articulation of r. If they are right, an explanation of the same type may perhaps be sought for the change er to ar in English, but little is known about the pronunciation of Engl. r half a millennium ago, though its modern realizations, both southern British and American, are not ancient.

WORD ORIGINS

Cobbler and clobber. I received two comments on clobber, for which I am grateful. Here I would like to add something to what I said in my post. Skeat has a note on clopping, which I have known for a long time but did not include in the original discussion. Clop, a phonetic variant of clap, meant and still means (in dialects) “to adhere, cling to.” On the other hand, clop ~ klop is a sound imitative verb (to go clop-clop), related to Dutch kloppen and German klopfen “to knock.” Clob and clop may be variants of the same word, as are cob and cop in some of their meanings, while clobber “a black paste used by cobblers to fill up and conceal cracks in the leather of boots and shoes” seems to have something to do with “adhering.” If there were homonyms clop ~ clob meaning “adhere, stick to” and “knock,” they were probably often confused, and then clobber becomes rather transparent. Perhaps (if we accept the idea of metathesis, that is, a transposition of sounds in lob ~ obl) those words throw a sidelight on cobbler (the designation of someone who knocks on nails and makes parts of leather adhere to one another) and cobble.

Cockney. I will reproduce the question. “At the Greenhill Oak pub, Cuckney, Nottinghamshire, amongst other historical claims, notices state that in the reign of Edward III, the duke of Portland had incompetent men looking after the King’s horses (palfreys). They regularly shoed them badly, and the Duke was obliged to supply others costing 4 marks each. So Cuckney became used as a term for idiot, and changed to Cockney. Local tradition or just whimsy?” (I knew only shod as the past tense of the verb shoe, but the OED reassured me that shoed, though rare, also exists. This, however, is beside the point.) The story looks as though it were cut out of the whole cloth. The initial meaning of cockney was “pampered child, weakling,” not “simpleton, fool.” The Greenhill pub anecdote has no currency outside its walls, and if there were a grain of truth in it, etymologists would have investigated it long ago. Besides, cockney never had u in the first syllable. In my etymological dictionary, a long entry is devoted to the origin of this difficult word. It did indeed surface in the reign of Edward III and may have been borrowed from French. Its native homonym meant “cock’s egg” (that is, “a bad egg”).

Mirror. Is it connected with German Meer “sea”? No, it is not. Its root also occurs in admire and miracle, which means “to look.”

Opaque names. “Do we know when English people stopped recognizing the etymology of given names, that is, when did the English no longer recognize Edward, Edith, etc, as meaning ‘Wealth Guard,’ ‘War Wealth’, etc.?” The problem with such names is the same as with all so-called disguised compounds. As time goes on, their elements change phonetically and/or alter their meanings, so that their initial signification can no longer be recognized. Sometimes the change is slight. Those who rhyme Sunday with Grundy are one step away from sun + day. Monday is worse, because mon- is far removed from the modern pronunciation of moon. Cupboard is still worse, and if it were spelled cubbard (like Hubbard), no one would be able to guess its origin. Bon- in bonfire is a shortened form of bone, but who will believe it without consulting a dictionary? In Edward, -ward still resembles ward(en)/guard(ian), but ed- goes back to ead “property.” Since the word has not continued into Modern English, the sum has become obscure. Edith contains two lost words: ead, as in Edward, and guth “war, battle” (does the whole mean “war wealth”?). English is full of disguised compounds, including such short words as barn (originally “barley house”) and bridal, which at one time was not an adjective but a noun meaning “ale drunk at a wedding.” Names do not have to change so radically (compare Wolfgang), but they most often do.

I will answer some of the questions “left behind” on the last Wednesday (Othin’s/Odin’s day) of November, in the next set of “gleanings.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as

An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins,

The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to

[email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”