new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: thomas hardy, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: thomas hardy in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Celine Aenlle-Rocha,

on 9/18/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

Philosophy,

Thomas Mann,

Language,

thomas hardy,

renaissance,

francis bacon,

beethoven,

Charles Perrault,

*Featured,

modern literature,

Ben Hutchinson,

European identity,

Late Style and its Discontents,

Lateness and Modern European Literature,

modern european literature,

modernism in literature,

post-Enlightenment,

The old age of the world,

Add a tag

At the home of the world’s most authoritative dictionary, perhaps it is not inappropriate to play a word association game. If I say the word ‘modern’, what comes into your mind? The chances are, it will be some variation of ‘new’, ‘recent’, or ‘contemporary’.

The post The old age of the world appeared first on OUPblog.

By: LaurenH,

on 6/23/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Arts & Humanities,

book vs movie,

far from the madding crowd,

Books,

Literature,

Videos,

adaptation,

thomas hardy,

comparisons,

Oxford World's Classics,

film adaptation,

*Featured,

victorian literature,

Add a tag

A new film adaptation of Far From the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy was recently released, starring Carey Mulligan as the beautiful and spirited Bathsheba Everdene and Matthias Schoenaerts, Tom Sturridge, and Michael Sheen as her suitors.

The post Book vs. Movie: Far From the Madding Crowd appeared first on OUPblog.

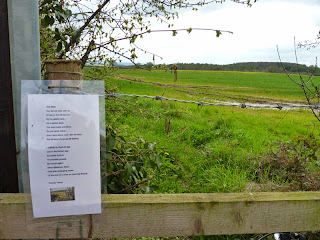

Out with Marjorie the other week, pootling to the Post Office which is two miles away. On the way back, I spotted a notice pinned to a gate post and, as one does, stopped to investigate.

However, it wasn't a planning application for a new housing estate (although that is in the pipeline for this area). It was a Thomas Hardy poem. Rather random, but lovely.

The Walk

You did not walk with me

Of late to the hill-top tree

By the gated ways,

As in earlier days;

You were weak and lame,

So you never came,

And I went alone, and I did not mind,

Not thinking of you as left behind.

I walked up there to-day

Just in the former way;

Surveyed around

The familiar ground

By myself again:

What difference, then?

Only that underlying sense

Of the look of a room on returning thence.

Pondering this and wondering 'who, what why and when?', I cycled on. And came then stopped.

Another country poem, pinned to another gatepost, with the brooding Wrekin just showing in the background.

A sonnet, by John Clare.

A Spring Morning

THE Spring comes in with all her hues and smells,

In freshness breathing over hills and dells;

O’er woods where May her gorgeous drapery flings,

And meads washed fragrant by their laughing springs.

Fresh are new opened flowers, untouched and free

From the bold rifling of the amorous bee.

The happy time ofsinging birds is come,

And Love’s lone pilgrimage now finds a home;

Among the mossy oaks now coos the dove,

And the hoarse crow finds softer notes for love.

The foxes play around their dens, and bark

In joy’s excess, ’mid woodland shadows dark.

The flowers join lips below; the leaves above;

And every sound that meets the ear is Love.

I have been meaning to read Thomas Hardy for ages so when Danielle proposed we read Far From the Madding Crowd together it was easy to say yes. I was expecting a very depressing book because that’s my impression of Hardy, but I apparently managed to read his least depressing story. In fact, as I mentioned when I began the book, it was actually full of humor. The humor fades out to occasional as the book progresses and the farmhands are always the ones who provide it, which ends up coming across as mocking the uneducated worker at times.

The story is about Bathsheba, a young, pretty and clever woman whom Gabriel Oak declares vain upon first meeting her. Bathsheba ends up inheriting her uncle’s farm and instead of hiring someone to take care of it for her, decides to do it herself. It is a brave move on her part since women aren’t supposed to have a head for farming or business, but she holds her own and even does better than many. Unfortunately it is subtly hinted that part of her success comes from the use of her feminine charms to disarm the men and confuse them into paying her more for her grain.

Bathsheba’s strength is also further undermined by the steady Gabriel Oak who, unbeknownst to Bathsheba, performs many of the duties the hired overseer would do if Bathsheba had decided to have one. Oak begins the book as his own farmer, just starting out with his own sheep, an undertaking he has scrimped and saved for and invested everything in. All is going well until he decides to get a new dog to help his ageing dog herd the sheep. Only the new dog takes too well to his sheep herding training and manages to herd the entire flock of sheep off a cliff! I know I am not supposed to find this funny but it makes me laugh every time I think about it. Gabriel is ruined and ends up working as the shepherd for Bathsheba on her farm. Oh, and Oak loves Bathsheba and when he was still a farmer had asked if he could court her and she turned him down with “You’re a nice man and all but I’m not interested in marrying so can we just be friends?”

Bathsheba’s farming neighbor is Mr. Boldwood who is, as his name suggests both wooden and bold. First we get the wood. A prosperous farmer, he is the most eligible bachelor around but in spite of all the ladies trying to catch him he is just not interested. His inability to be swayed by flirtation provokes Bathsheba to send him a Valentine card as a joke. But the joke backfires as the wooden man suddenly is swept away by love and becomes bold to the point of harassment. Bathsheba does not love him though and when finally pressed, tells him so, even says she suspects she would never love him. She apologizes repeatedly for her bad joke but Boldwood refuses to leave the woman alone so certain is he that she will eventually love him back.

When the dashing Sergeant Troy meets Bathsheba one evening as she is walking around her farm checking on things before retiring for the night, he is immediately charmed. Troy catches his spur in Bathsheba’s dress which forces many minutes of inappropriate closeness while Troy bumblingly (on purpose) disentangles himself. Troy is actually in love with another woman with plans to marry her, but is so taken up with the challenge of making Bathsheba love him that he abandons poor Fanny Robin to an ultimately sad end. Bathsheba falls hard for Troy just like boldwood fell for her. Troy’s flirtation is relentless and he is all things charming and irresistible given that her other prospects were Oak and Boldwood. The pair marry which causes Boldwood to slip into a depression so deep he begins neglecting his farm and losing money.

Bathsheba starts losing money too because it turns out Troy is not what he represented himself to be and takes distinct pleasure in neglecting his new duties as head of farm and instead going to the racetrack to lose Bathsheba’s money. If this isn’t soapy enough for you, the suds increase when Troy runs away, goes skinny dipping in the ocean, gets caught in a ripetide and rescued just in time by some men in a boat at which point he decides to ship out with them. But someone from the neighborhood saw Troy being pulled out to sea and missed the rescue. Of course no body is found. Nonetheless, Boldwood is back on harassment duty and forces Bathsheba into to agreeing to marry him after seven years when Troy can be legally declared dead.

The years fly by but as the seven year date approaches and Boldwood is readying to swoop in for the win, well, you will just have to read the book yourself to find out. It’s very Days of Our Lives. But the book can’t end without Bathsheba being married because a woman on her own is not allowable.

Throughout the book Hardy makes comments and observations about marriage and relations between men and women. His culminating statement comes down to this:

This good-fellowship—camaraderie—usually occurring through similarity of pursuits, is unfortunately seldom superadded to love between the sexes, because men and women associate, not in their labours, but in their pleasures merely. Where, however, happy circumstance permits its development, the compounded feeling proves itself to be the only love which is strong as death—that love which many waters cannot quench, nor the floods drown, beside which the passion usually called by the name is evanescent as steam.

Far From the Madding Crowd was an early novel, published the same year Hardy married his first wife with whom he was passionately in love. The pair eventually became estranged and two years after her death in 1912, Hardy married his secretary who was 39 years his junior. So I’m not sure one would want to take any kind of relationship advice from him. I have to admit though, the man really knew how to rock a mustache.

Do pop over to A Work in Progress for Danielle’s thoughts about the book.

Filed under:

Books,

Reviews Tagged:

Thomas Hardy

By: Hannah Paget,

on 8/30/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Louis simpson,

*Featured,

war poetry,

jon stallworthy,

WWI centenary,

first world war poetry,

men who march away,

On the Late Massacre in Piedmont,

the heroes,

Books,

Literature,

war,

WWII,

thomas hardy,

emily dickenson,

extract,

John Milton,

Humanities,

Add a tag

‘Poetry’, Wordsworth reminds us, ‘is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’, and there can be no area of human experience that has generated a wider range of powerful feelings than war: hope and fear; exhilaration and humiliation; hatred—not only for the enemy, but also for generals, politicians, and war-profiteers; love—for fellow soldiers, for women and children left behind, for country (often) and cause (occasionally).

So begins Jon Stallworthy’s introduction to his recently edited volume The New Oxford Book of War Poetry. The new selection provides improved coverage of the two World Wars and the Vietnam War, and new coverage of the wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Below is an extract of two poems from the collection.

JOHN MILTON

1608–1674

On the Late Massacre in Piedmont* (1673)

Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughtered saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold,

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old

When all our fathers worshipped stocks and stones,

Forget not; in thy book record their groans

Who were thy sheep and in their ancient fold

Slain by the bloody Piedmontese that rolled

Mother with infant down the rocks. Their moans

and his Latin secretary, John Milton.

The vales redoubled to the hills, and they

To Heaven. Their martyred blood and ashes sow

O’er all th’ Italian fields where still doth sway

The triple tyrant, that from these may grow

A hundredfold, who having learnt thy way,

Early may fly the Babylonian woe.

* The heretical Waldensian sect, which inhabited northern Italy (Piedmont) and southern France, held beliefs compatible with Protestant doctrine. Their massacre by Catholics in 1655 was widely protested by Protestant powers, including Oliver Cromwell and his Latin secretary, John Milton.

LOUIS SIMPSON

The Heroes (1955)

I dreamed of war-heroes, of wounded war-heroes

With just enough of their charms shot away

To make them more handsome. The women moved nearer

To touch their brave wounds and their hair streaked with gray.

I saw them in long ranks ascending the gang-planks;

The girls with the doughnuts were cheerful and gay.

They minded their manners and muttered their thanks;

The Chaplain advised them to watch and to pray.

They shipped these rapscallions, these sea-sick battalions

To a patriotic and picturesque spot;

They gave them new bibles and marksmen’s medallions,

Compasses, maps, and committed the lot.

A fine dust has settled on all that scrap metal.

The heroes were packaged and sent home in parts

To pluck at a poppy and sew on a petal

And count the long night by the stroke of their hearts.

Image credit: Menin Gate, Ypres, Belgium. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post War poetry across the centuries appeared first on OUPblog.

Almost two weeks ago now I started reading Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd. I’ve not ever read Hardy before. I know! I have seen a movie version of Tess a very long time ago, does that count? Anyway, whenever I’ve mentioned Hardy on this blog over the years I’ve gotten two reactions:

- He’s sooo good, you have to read him!

- He’s really depressing so be prepared

The so good and the really depressing even come from the same people, implying that depressing does not mean a bad book. So when I began Far from the Madding Crowd I was expecting a really good book that is also a downer. Maybe it’s me, or maybe this is Hardy’s only non-depressing book, but I’ve been laughing while reading it. Laughing a lot. This I did not expect and was confused at first, worried perhaps I was misreading or something. But no, Hardy is funny. How can this not make you laugh?

Oak sighed a deep honest sigh—none the less so in that, being like the sigh of a pine plantation, it was rather noticeable as a disturbance of the atmosphere.

Or this:

‘Come, Mark Clark—come. Ther’s plenty more in the barrel,’ said Jan. ‘Ay—that I will, ’tis my only doctor,’ replied Mr. Clark, who, twenty years younger than Jan Coggan, revolved in the same orbit. He secreted mirth on all occasions for special discharge at popular parties.

Or that one man in the neighborhood is known only as “Susan Tall’s husband” because he has no distinguishing characteristics of his own. I find myself giggling every time Susan Tall’s husband shows up, which isn’t often enough if you ask me, but I suppose you have to play lightly with that joke or it will wear itself out too quickly.

It’s not like Hardy’s humor slaps you in the face, it is pretty subtle most of the time. It doesn’t make me laugh out loud but it does make me grin. I’m far enough along to know there is trouble ahead for Bathsheba, but I’m not sure that it will be enough to turn everything depressing. Am I safe to put my hanky away or should I keep it in reserve?

Filed under:

Books,

In Progress Tagged:

Thomas Hardy

By: DanP,

on 7/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

wilfred owen,

war poetry,

The Great War,

john balaban,

jon stallworthy,

new oxford book of war poetry,

stallworthy,

adiuzdccgw8,

dexyjf_dppc,

balaban,

ymhsxz5,

wyton,

Books,

History,

Poetry,

WWII,

Videos,

Vietnam War,

thomas hardy,

soldiers,

iraq war,

America,

Multimedia,

British,

wwi,

first world war,

Second World War,

*Featured,

Add a tag

There can be no area of human experience that has generated a wider range of powerful feelings than war. Jon Stallworthy’s celebrated anthology The New Oxford Book of War Poetry spans from Homer’s Iliad, through the First and Second World Wars, the Vietnam War, and the wars fought since. The new edition, published to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, includes a new introduction and additional poems from David Harsent and Peter Wyton amongst others. In the three videos below Jon Stallworthy discusses the significance and endurance of war poetry. He also talks through his updated selection of poems for the second edition, thirty years after the first.

Jon Stallworthy examines why Britain and America responded very differently through poetry to the outbreak of the Iraq War.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy on his favourite war poems, from Thomas Hardy to John Balaban.

Click here to view the embedded video.

As The New Oxford Book of War Poetry enters its second edition, editor Jon Stallworthy talks about his reasons for updating it.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy is a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University. He is also a Fellow of the British Academy. He is the author of many distinguished works of poetry, criticism, and translation. Among his books are critical studies of Yeats’s poetry, and prize-winning biographies of Louis MacNiece and Wilfred Owen (hailed by Graham Greene as ‘one of the finest biographies of our time’). He has edited and co-edited numerous anthologies, including the second edition of The New Oxford Book of War Poetry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

The post What can poetry teach us about war? appeared first on OUPblog.

If you’d asked me what I’d expect to be working on five years ago, I definitely wouldn’t have said ‘I’ll be retelling Tess of the d’Urbervilles for children.’ I might have shuddered at the very idea of compressing a book I loved so much into 6,500 words. I’d have thought of Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, and worse, Bowdler!

But I’m in good company. Michael Rosen retold Romeo and Juliet, and recently Philip Pullman published his version of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I knew the publishers of the Real Reads series from another connection, and sitting in their garden one day I gulped and said ‘I’d like to do one of those’ - and then wondered what I’d let myself in for.

When I looked at the books I began to see the point, and the skilful way these little books lead readers from the shallows into deeper, perhaps more satisfying waters. Gill Tavner, who tackled Dickens, Jane Austen and more greats for Real Reads, puts it this way:

‘I have long thought that there must be a way of making the qualities of ‘classics’ accessible to most readers, but I was unconvinced that abridging was the answer. As a mother of two young children, I have endured the pain of reading abridged fairy tales and Disney films. These often machine-gun the reader with a list of events. Rarely do they offer the reader an opportunity to develop interest in or appreciation of varied vocabulary, style or themes. Do abridged versions need to be like this? Surely there is a way to make an abridged version an enjoyable and enriching rather than simply informative reading experience? Surely this is an important distinction if we aim to nurture keen, confident readers?’

The format for Real Reads includes a list of the main characters, questions to follow up the story, a list of follow-up books, films and websites, the historical context of the book and some thoughts about what readers might find if they braved the whole thing. There are also some lovely illustrations. The books were originally intended for children aged about 8-11, but they sell well to readers of English as a Second Language, and to adults who want a way into difficult books - I’ve just ordered a copy of the Ramayana, for example, as I just can’t get into reading the whole thing.

I was lucky - I got to choose my writer and which books I’d like to do. Tess of the d’Urbervilles was the first, and perhaps the easiest. I had to retell the story in a way which makes it come alive, and with something of Hardy’s style. My usual writing voice is about as far away from Hardy’s as you could get, so it was quite a challenge.

But I learned a lot from the process. First, I learned to step a long way back from the story, not to immerse myself in it. What were the key themes, the journeys of the characters? What was essential? What made it live? Those are important questions to ask of any book.

Then I realised that I couldn’t go through chapter by chapter summing them up as I went. That would end up as a list of events, not a story. I had to put the book aside and tell Tess’s story from her humble beginnings to her tragic arrest for murder. And I had to think of Hardy’s feelings about Tess. He used a sub-title for the book - ‘A Pure Woman’. He clearly didn’t think Tess is to blame for what happens to her, but blamed a society with double standards. Angel Clare, who becomes Tess’s husband, has had an affair, but he leaves Tess when she admits to the same.

There were some tricky issues too - like the scene where Alec d’Urberville rapes Tess in the forest. How could I write that essential scene for a children’s book? Hardy isn’t explicit, but he’s clear enough. I watched all the films and TV series for some help - but the directors fudged the issue, or came down on one side or the other. Here’s how I did it:

'Alec got lost in the wood. Tess was exhausted, and he helped her to lie down on the ground and covered her with his coat, while he went off to find his bearings.

When he came back, she was asleep. Alec could just make out her face in the dark. He knelt beside her, his cheek next to hers. He could still see a tear on her face.

As her people would say, it was to be. This was the last they would see of the Tess who left home to try her fortune.

A chasm was to divide her from that former self.'

The last sentence is direct from Hardy’s book. The scene’s very close to his own.

The Mayor of Casterbridge was the most difficult of the Hardy novels to retell - it’s so rich in plot, so much happens, that I felt I had to butcher some of the story to get it into the word count. But I learned so much about editing, about looking at a book from a long way back, and from very close up, from the work I did on Hardy’s books. I still love the originals. But I’m quite proud of what I’ve done with them.

The Mayor of Casterbridge was the most difficult of the Hardy novels to retell - it’s so rich in plot, so much happens, that I felt I had to butcher some of the story to get it into the word count. But I learned so much about editing, about looking at a book from a long way back, and from very close up, from the work I did on Hardy’s books. I still love the originals. But I’m quite proud of what I’ve done with them.

‘What are your books about?’ That’s a question I often get asked when I say I’m a novelist writing for, or about, young adults. My first book, Vintage, is easy to describe. Vintage is about a 17 year old girl living in 2010 who swaps places with a seventeen year old living in 1962. That seems to satisfy, and interest people, including adults who were around in 1962!

The second book, Closer, is harder to describe. In the blurb on the back we chose to focus on Mel, the main character - on who she is, her gritty and quirky take on the world, and on her finding the courage to speak out. But I was a bit naive if I thought it would stop there. As soon as the book came out, the reviews on Amazon and in magazines spelt out the story - Closer is about a girl whose stepfather gets too close. It involves sexual abuse.

Some parents have said that they don’t think their children are ready to read it, and I can understand that. Some young people have said they don’t want to read about incest or abuse (yukk!, as one graphically put it). But the feedback I’ve had from those who read it is that they find Closer inspiring, compelling and not remotely explicit. And some of the best feedback has been from teachers and social workers who have said that it’s realistic - better than reading a case study, one said. I have to admit I'm really proud of that.

There’s something about ‘issue’ books which puts me off too. If I feel I’m being asked to think in a particular way, if I feel lectured or taught, it’s a huge turnoff. I want to be told a story. I want to find a way of getting inside someone else’s world and knowing something I’d never otherwise have known. I want to be gripped, to have to read on, and to be satisfied by the ending even if it doesn’t give me all the answers. I want to be interested in the characters and where they’re going. I want to make my own mind up.

I've learned so much from reading novels about difficult times in their characters' lives. Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar comes to mind, and Roddy Doyle's The Woman who walked into Doors. Most recently, Patrick Ness wrote so movingly about grief in A Monster Calls. When something new comes up in my life, whether it's working out how to knit socks or how to find a way through grief, I'll reach for a book, or the internet, or a friend - or all three.

It’s a conundrum, how to pose questions about an issue without giving easy answers - and then how to describe the book without giving away the story. I wrote Closer partly because I’d read the YA novels I could find at that time about sexual abuse, and the outcome in the stories was often disastrous. I knew from my work as a psychotherapist that this wasn't always the case, or it didn't have to be.

I imagined a reader, possibly young, who read these books and had gone through something like Mel’s experience - or had a friend going through it. I wanted her, or him, to have a story where there are no monsters, and where there’s a way through. I feel passionately about that. And when sexual abuse has been so much around in the news in the last few months, we need ways of making sense of it, and stories about coming through.

So that's my first blog for ABBA - phew!

But I still don’t know how to say what Closer is about...

Bloomsbury has published my story about Facebook in their series Wired Up for reluctant readers. It's called Breaking the Rules.

I've retold three Thomas Hardy novels for Real Reads - The Mayor of Casterbridge, Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd. They're read by 9-13s, and by adults learning English as a foreign language.

By: Kirsty,

on 1/16/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

UK,

thomas hardy,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Humanities,

dorset,

hardy,

*Featured,

phillip mallett,

westminster abbey,

16 january,

stinsford,

thomas hardy's funeral,

under the greenwood tree,

wessex,

hardy’s,

‘hardy,

Add a tag

By Phillip Mallett

At 2.00 pm on Monday 16 January 1928, there took place simultaneously the two funerals of Thomas Hardy, O.M., poet and novelist. His brother Henry and sister Kate, and his second wife Florence, had supposed that he would be buried in Stinsford, close to his parents, and beneath the tombstone he had himself designed for his first wife, Emma, leaving space for his own name to be added. But within hours of his death on 11 January, Sydney Cockerell and James Barrie had established themselves at his home at Max Gate, and determined that he should be laid in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Trapped between family pieties and what the men of letters bullyingly assured her were the claims of ‘the nation’, the exhausted Florence agreed to a compromise as grotesque as anything in Hardy’s fiction: his ashes were be buried in the Abbey, together with a spadeful of Dorset earth, and his heart in Stinsford churchyard.

![Thomas Hardy's Grave by Caroline Tandy [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons Thomas Hardy's grave, Stinsford churchyard - geograph.org.uk - 336325](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/96/Thomas_Hardy%27s_grave%2C_Stinsford_churchyard_-_geograph.org.uk_-_336325.jpg/256px-Thomas_Hardy%27s_grave%2C_Stinsford_churchyard_-_geograph.org.uk_-_336325.jpg) The Dorset funeral was a quiet affair. Kate, who went to the Abbey, while Henry attended in Stinsford, recorded that ‘the good sun shone & the birds sang & everything was done simply, affectionately & well.’ That at the Abbey was a national event. Crowds waited outside in the rain to file past the open grave; Stanley Baldwin and Ramsay MacDonald were among the pall bearers. So too were Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw, as ill-matched in their height as in their politics; according to Shaw’s secretary, Blanche Patch, Kipling shook hands ‘hurriedly, and turned away as if from the Evil One’. Hardy had once proposed the creation of ‘a heathen annexe’, suitable for non-believers like Swinburne, Meredith and himself, but T. E. Lawrence, absent in Karachi, thought he might have been amused at his belated capture by Church and Establishment: ‘Hardy was too great to be suffered as an enemy to their faith: so he must be redeemed.’

The Dorset funeral was a quiet affair. Kate, who went to the Abbey, while Henry attended in Stinsford, recorded that ‘the good sun shone & the birds sang & everything was done simply, affectionately & well.’ That at the Abbey was a national event. Crowds waited outside in the rain to file past the open grave; Stanley Baldwin and Ramsay MacDonald were among the pall bearers. So too were Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw, as ill-matched in their height as in their politics; according to Shaw’s secretary, Blanche Patch, Kipling shook hands ‘hurriedly, and turned away as if from the Evil One’. Hardy had once proposed the creation of ‘a heathen annexe’, suitable for non-believers like Swinburne, Meredith and himself, but T. E. Lawrence, absent in Karachi, thought he might have been amused at his belated capture by Church and Establishment: ‘Hardy was too great to be suffered as an enemy to their faith: so he must be redeemed.’

Dorchester is famously Hardy’s ‘Casterbridge’, at the centre of Wessex, and many a biographer has remarked that his heart rightly belongs there. Yet when Hardy began writing, he had no reason to suppose that for more than fifty years his imagination would linger in the southwestern counties of England. Rather than a calculated first step, as he later liked to suggest, the name ‘Wessex’ was introduced casually in Far from the Madding Crowd, in a description of Greenhill Fair as ‘the Nijni Novgorod of Wessex’, when most readers must have been struck as much by the reference to Nijni Novgorod as by the disinterment of the ancient name of Wessex. In a miniature way the sentence is revealing about Hardy’s position as a regional writer. In describing the sheep fair, on ‘the busiest, merriest, noisiest day of the whole statute number’, the narrator associates himself not only with its regular visitors but also with those outsiders for whom Greenhill and Nijni Novgorod, since 1817 the site of the annual Makaryev Fair, are equally places to read about rather than to visit. He is at once a participant in local life and custom, and an educated observer of it.

Perhaps it is only just that the town has a slightly uneasy relation with Hardy and his legacy. It is at least a profitable one. Tourists began using his fiction as a guide to the area as early as the 1890s, and Hardy was canny enough to identify his work with the Wessex ‘brand’; his first volume of short stories was titled Wessex Tales, his first collection of verse Wessex Poems. ‘Wessex’ was not only what he knew; it was what he brought to the literary market-place. The brand remains: contemporary visitors can stay at the Wessex Royale hotel, travel by Wessex taxis, or have their used cars broken up by Wessex Metals. But the visitor who asks in the town centre for directions to Max Gate, or to Hardy’s birthplace at Higher Bockhampton, is likely to ask in vain. When in 1999 Prince Edward was created Earl of Wessex (an earldom defunct since the eleventh century), it was the film Shakespeare in Love, not Hardy’s work, which suggested the title.

Divided in life, then, as divided in death? The trope is obviously tempting. Hardy’s fiction is full of characters caught between two ways of life, of natives who return to find that rather than ‘native’ they have become harbingers of a wider and typically newer way of life. But the simple metaphor of division does less than justice to Hardy’s constant negotiation with the class stratification of Victorian society. Part of what Hardy took from his Wessex background, and his family ties, was the strength and will to leave, but the struggle to return imaginatively, and to recreate a past informed by the sense of its own passing, marks all his fiction and most of his verse. It is not division for which Hardy should be remembered, still less in lazy terms of a ‘snob’ trying to disown his roots, or a ‘self-educated peasant’ who could never disguise them, but the search for connection, between social groups, modes of speech, aspiration and memory, the complex sense of participancy and the still more complex right of individuals to be themselves. If the double funerals have an element of the grotesque, easily attached to the marginalising adjective ‘Hardyan’, his achievement as a poet and novelist makes him central to the ‘great tradition’ of English writing.

Phillip Mallett teaches English Literature at the University of St Andrews. He is editor of the Thomas Hardy Journal and Vice-Preseident of both the Thomas Hardy Society and the Thomas Hardy Association. His edition of Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree for Oxford World’s Classics is forthcoming in May 2013.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Thomas Hardy’s Grave by Caroline Tandy [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The two funerals of Thomas Hardy appeared first on OUPblog.

In a long profile of J.K. Rowling at The New Yorker, journalist Ian Parker shared some juicy tidbits about The Casual Vacancy–a novel for adults by the Harry Potter author that has been guarded by nondisclosure agreements and a strict embargo.

In a long profile of J.K. Rowling at The New Yorker, journalist Ian Parker shared some juicy tidbits about The Casual Vacancy–a novel for adults by the Harry Potter author that has been guarded by nondisclosure agreements and a strict embargo.

If you want to find out more about the top secret novel before it comes out on September 27th, you should read the whole “Mugglemarch” profile.

SPOILER ALERT: If you don’t want to know more about the book, you should stop reading now. Below, we’ve collected five spoilers from the article that show us more about the book.

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Lucia Perillo,

on 5/3/2012

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

William Shakespeare,

Thomas Hardy,

Charles Baxter,

John Berryman,

T S Eliot,

Sylvia Plath,

Laura Kasischke,

Original Essays,

Lucia Perillo,

James Dickey,

Add a tag

It should not be so hard to write both poetry and fiction. Both arts, after all, make use of the same materials, words and punctuation. Poems frequently utilize the strategies of fiction, which in turn, in the hands of the best writers, listens carefully to the sounds that it is making. Even poems which do [...]

By: Alice,

on 2/22/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

thomas hardy,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

dude,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Jude the Obscure,

oelrichs,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

I borrowed the title of this post from an ad for an alcoholic beverage whose taste remains unknown to me. The picture shows two sparsely clad very young females sitting in a bar on both sides of a decently dressed but bewildered youngster. I assume their age allows all three characters to drink legally and as much as they want. My concern is not with their thirst but with the word dude. After all, this blog is about the origin of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, rather than the early stages of alcoholism.

My experience confirms the observations of several people who have published on dude: it has become an all-purpose form of address among young men. Surveys show that college age women also use it, but my notes contain no examples. In future, dude may develop like guy. You guys is now unisex; one day, you dudes may become equally “cool.” A very full overview of the history of dude can be found in the journal Comments on Etymology 23/1, 1993, 1-46. Not surprisingly, the origin of dude is unknown. Monosyllables beginning and ending with b, d, g (and even with p, t, k) are the dregs of etymology. Consider bob, bib, gig, gag, and tit (exchange tit for tat if you care). I believe that kick is a borrowing from Scandinavian, but its Icelandic etymon is merely “expressive” and shares common ground with bib, bob, and their ilk.

Dude is a member of a small but happy family: dod “cut off, lop, shear,” dud, duds, and dad. Only did has an ancestry any word can be proud of; the same is partly true of agog, but then agog is not a monosyllable. The OED (in an entry first published in 1897) called dude a factitious slang term. This statement inspired a rebuff from one of our best experts in the history of slang: “There is not a shred of evidence that dude arose factitiously, i.e., somehow artificially. OED simply should have said: ‘Origin unknown’.” Yet a non-artificial origin of dude is hard to come by. I never miss an opportunity to refer to Frank Chance and Charles P.G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, a sadly underquoted, undercited work (among the greats only Skeat seems to have recognized its value). This is what Scott wrote about dude:

“A slang term which has been the subject of much discussion. It first became known in colloquial and newspaper use at the time of the so-called ‘esthetic’ movement in dress and manners in 1882-3. The term has no antecedent record, and is prob. one of the spontaneous products of popular slang. There is no known way, even in slang etymology, of ‘deriving’ the term, in the sense used, from duds (formerly sometimes spelled dudes…), clothes in the sense of ‘fine clothes’; and the connection, though apparently natural, is highly improbable.”

It will be seen that Scott and the OED had a similar attitude toward dude.

Perhaps both the OED’s editor James A.H. Murray and Scott were right. Yet one point should be made in connection with their opinion. The history of slang words deserves as much attention as that of more genteel words. Quite often even good dictionaries, in the etymological parts of their entries, confine themselves to the “explanation” slang, as though saying that a word had at one time was “low” sheds ligh

.jpg?picon=1806)

By:

Susan Price,

on 2/6/2009

Blog:

An Awfully Big Blog Adventure

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

teaching,

Thomas Hardy,

Rewriting,

Susan Price,

Ghost Drum,

creative writing groups,

rewrites,

Jordan,

ghost-writer,

Tess of the D'Urburvilles,

Creative Writing Classes,

Add a tag

When I was a child, our house was littered with drawings, on used, opened-out envelopes, or old wallpaper, and even drawing-pads. My brother drew dinosaurs or battles (and battling dinosaurs), my sister drew swimming seals or people, and my father's drawings were usually of aeroplanes or birds.

They all had one thing in common: there would be repeated attempts at the drawings. My Dad, for instance, would do a sketch of the whole plane, and then, underneath, another drawing of its undercarriage, and another of its wings. He hadn't been happy with the first drawing, so he practiced the bits he felt needed improving. Turn the paper over, and there would be another, larger, better drawing of the whole plane.

These sketches taught me something without my ever realising I'd learned anything at all - 'You won't get things right the first time, so repeat them until you do'.

My own drawings were usually of people. As a child, I drew far more than I wrote; in my early teens, I drew and wrote about equally. After my first book was accepted, when I was sixteen, writing took over from drawing (and I haven't seriously drawn anything for about thirty years now). But the lesson that I never knew I'd learned moved with me from drawing to writing. If I wasn't happy with something I'd written, I rewrote it – and if I still wasn't happy, I rewrote it again, and again, many times if need be, until I thought I couldn't improve it any more.

I didn't think I was doing anything noteworthy. Rewriting was part and parcel of writing. It was just what you did; as much a part of writing as using a pen.

Years passed, and, in the way of impoverished writers, I started teaching Creative Writing. But between you and me, gentle reader, I was puzzled as to what 'Creative Writing' was exactly. And even more puzzled as to what I could teach my students. If I had ever stopped to think about what I did when I wrote a book, I couldn't remember doing it.

I consulted a few 'How to Write' books, to find out what those authors told their students, and it was enlightening. “Oh, I do that! Who'd have thought it?” I resolved only to steal those 'creative writing' tips that I could honestly say I used myself. (So you'll hear only a perfunctory mention in my classes about keeping notebooks, or meditating, or doing ten minutes of 'automatic writing' every morning.) My classes were about setting scenes, writing dialogue, building plots. It never occurred to me to tell anyone to rewrite, because to me rewriting was writing. I didn't think anyone would need to be told that.

Slowly, over weeks, it became apparent to me that the idea of rewriting had never, ever occurred to many – not just a few, but many – of my students. A lot of them seemed to think it was cheating. A real writer, they seemed to think – Thomas Hardy, let's say – just sat down and wrote Tess of the D'Urbervilles straight off, from beginning to end, never blotting a word; and then he packed it off to his publishers who printed it without asking for a single change. That's the kind of genius he was. That's the way a real writer works.

If my students wrote a story, and found themselves dissatisfied with it, they concluded that it was another failure, put it away, and tried to forget about it. The next thing they wrote, that might be perfect.

“Couldn't you,” I suggested nervously, not at all sure I was on firm ground here, “couldn't you rewrite it?”

They were astonished. But they'd finished it! And it wasn't any good. What was the point of wasting more time on it?

“But nothing I've ever written,” I said, “was much good in its first draft. But if I like the idea – if there are bits that are good – I rewrite it, and improve it. I've rewritten some things dozens of times over. I rewrote the whole of GHOST DRUM six or seven times, and I rewrote the ending many more times than that.”

Some of the class were quite excited by this revolutionary idea. Others were as plainly horrified, reminding me of a little girl in Year 4 of a school I once visited. Her story was so good, I told her, that she should rewrite it. The look she gave me would have reduced a lesser writer to a pair of smouldering boots.

But having belatedly realised that rewriting was actually a tool of the writer's trade that I'd never before suspected I was using, I became evangelistic about it. “Rewrite!” I cried to each new intake of students. “You must rewrite!”

And then one of my students stopped me in my tracks by asking, “But how do I know what parts I have to rewrite? How do I know which words I should change?”

Well – er – quite. Obviously, these are the technical complexities Jordan was referring to when she spoke of her ghost writer 'putting it into book words'. When a writer, like wot I am, takes the raw first draft and puts it into book words, what exactly is it I are doing?

I hadn't a clue. Look, I only write the stuff – I don't waste my time thinking about it, any more than a ditch-digger thinks much about ditch-digging. She just heaves another shovel-ful of mud.

But there were my students, waiting for an answer. So I gave thinking about it a try. And boy, did my brain hurt...

To be continued....

Here in the UK it’s getting close to the time of year when school exam results start landing on doormats across the country (A-Level results are out on August 14th), which made me think back to the nail-biting morning waiting to see if I’d got the marks I needed for my university course (I did, phew). So, in the spirit of testing your knowledge to the maximum, today I bring you a handful of questions from our book So You Think You Know Thomas Hardy? by John Sutherland. I studied Hardy at high school, and while I have to confess that my 16-year-old self was less than enthusiastic about him, I have grown to appreciate his novels much more since.

Let’s get down to business. A few easy ones to start you off…

1. What is the name of the cow who is the occasion of Oak’s second meeting with Bathsheba in Far From The Madding Crowd?

2. What is Susan’s nickname among the children of the town in The Mayor of Casterbridge?

3. In The Woodlanders, of what does Grace dream, on her first night back at Hintock?

4. In Tess of the D’Urbervilles, who, as best the reader can piece together, are the Durbeyfield

children and what are their ages?

5. What did Jude’s father die of in Jude the Obscure?

OK. So you should be warmed up by now. Let’s get a little trickier.

6. In Far From The Madding Crowd, what is the great communal beer mug at Warren’s Malthouse

called, and why?

7. In The Mayor of Casterbridge, why does Henchard go to Mrs Goodenough’s ill-fated furmity tent?

8. Back to The Woodlanders. Why does Marty habitually call Giles (who calls her ‘Marty’) ‘Mr Winterborne’?

9. What colour are Tess’s eyes?

10. Jude (the Obscure) has given Arabella a framed lover’s photograph of himself. What happens to it?

Last set coming up - these are the hardest questions of all!

11. To what does Bathsheba attribute her lack of ‘capacity for love’?

12. ‘Casterbridge’, the narrator tells us, ‘announced old Rome in every street’. What can one read into this antiquarian observation, if anything?

13. What do Mr and Mrs Melbury wear to Giles’s ‘randy-voo’, intended to welcome Grace back as his lover?

14. What is ‘scroff’ and what part does it play in Tess’s downfall?

15. Jude and Sue sleep together at the old woman’s cottage, on their ill-fated day’s excursion. Do they do anything more than (literally) sleep?

Check back tomorrow for the answers!

ShareThis

I quoted part of this poem on Tuesday in my post for the Scholar's Blog Book Discussion on Penelope Lively's The House in Norham Gardens, but here's the poem in full:

Old Furniture

I know not how it may be with others

Who sit amid relics of householdry

That date from the days of their mothers' mothers,

But well I know how it is with me

Continually.

I see the hands of the generations

That owned each shiny familiar thing

In play on its knobs and indentations,

And with its ancient fashioning

Still dallying:

Hands behind hands, growing paler and paler,

As in a mirror a candle-flame

Shows images of itself, each frailer

As it recedes, though the eye may frame

Its shape the same.

On the clock's dull dial a foggy finger,

Moving to set the minutes right

With tentative touches that lift and linger

In the wont of a moth on a summer night,

Creeps to my sight.

On this old viol, too, fingers are dancing

-- As whilom

-- just over the strings by the nut,

The tip of a bow receding, advancing

In airy quivers, as if it would cut

The plaintive gut.

And I see a face by that box for tinder,

Glowing forth in fits from the dark,

And fading again, as the linten cinder

Kindles to red at the flinty spark,

Or goes out stark.

Well, well.

It is best to be up and doing,

The world has no use for one to-day

Who eyes things thus -- no aim pursuing!

He should not continue in this stay,

But sink away.

Also on Tuesday, I watched Michael Winterbottom's Jude, starring Christopher Eccleston as Jude. (I freely admit, I watched it for the sake of seeing David Tennant in his first ever (tiny) film role!) So it's been a Hardyesque week and I looked up some more of his poetry to share. Also on the theme of the past (which is appropriate to the Book discussion) is this:

The Ghost of the Past

We two kept house, the Past and I,

The Past and I;

I tended while it hovered nigh,

Leaving me never alone.

It was a spectral housekeeping

Where fell no jarring tone,

As strange, as still a housekeeping

As ever has been known.

As daily I went up the stair,

And down the stair,

I did not mind the Bygone there --

The Present once to me;

Its moving meek companionship

I wished might ever be,

There was in that companionship

Something of ecstasy.

It dwelt with me just as it was,

Just as it was

When first its prospects gave me pause

In wayward wanderings,

Before the years had torn old troths

As they tear all sweet things,

Before gaunt griefs had torn old troths

And dulled old rapturings.

And then its form began to fade,

Began to fade,

Its gentle echoes faintlier played

At eves upon my ear

Than when the autumn's look embrowned

The lonely chambers here,

The autumn's settling shades embrowned

Nooks that it haunted near.

And so with time my vision less,

Yea, less and less

Makes of that Past my housemistress,

It dwindles in my eye;

It looms a far-off skeleton

And not a comrade nigh,

A fitful far-off skeleton

Dimming as days draw by.

And finally, a poem, written in July 1914, about a poet:

A Poet

Attentive eyes, fantastic heed,

Assessing minds, he does not need,

Nor urgent writs to sup or dine,

Nor pledges in the roseate wine.

For loud acclaim he does not care

By the august or rich or fair,

Nor for smart pilgrims from afar,

Curious on where his hauntings are.

But soon or later, when you hear

That he has doffed this wrinkled gear,

Some evening, at the first star-ray,

Come to his graveside, pause and say:

'Whatever his message his to tell

Two thoughtful women loved him well.'

Stand and say that amid the dim:

It will be praise enough for him.

![Thomas Hardy's Grave by Caroline Tandy [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons Thomas Hardy's grave, Stinsford churchyard - geograph.org.uk - 336325](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/96/Thomas_Hardy%27s_grave%2C_Stinsford_churchyard_-_geograph.org.uk_-_336325.jpg/256px-Thomas_Hardy%27s_grave%2C_Stinsford_churchyard_-_geograph.org.uk_-_336325.jpg)

In

In

Hi - enjoyed your post - are you Sue Clarke's friend Maxine? I'm Celia who lives down the road from her - we seem to have both turned to children's writing at the same time, roughly, so I've heard about you from her (if you're the right one!)

Greetings!

Celia

Hi Celia

Yes, of course, such coincidences!

Give her a wave and a hug from me.

Maxine.