February is African American History Month. Sharing these books with young readers comes with the responsibility to discuss ... progress towards equality.

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Ku Klux Klan, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

Blog: The Children's Book Review (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Historical Fiction, Slavery, featured, World War I, Military, Jacqueline Woodson, Roaring Brook Press, Middle Grade Books, Random House Books for Young Readers, Michael Morpurgo, Equal Rights, Steve Sheinkin, Scholastic Press, Deborah Wiles, World War 2, Sharon M. Draper, Lea Wait, Freedom Summer, Ku Klux Klan, Islandport Press, Nancy Paulsen Books, Military Stories, Feiwel & Friends books, Sharon Lovejoy, Ages 9-12, Book Lists, Black History Month, Civil Rights, Books for Boys, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Award Winners, Books for Girls, African American History Month, Teens: Young Adults, Cultural Wisdom, Poetry & Rhyme, Add a tag

Blog: The Children's Book Review (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Ages 9-12, Diversity, Historical Fiction, Black History Month, Civil Rights, African American Authors, African American, featured, Books for Boys, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Great Depression, Books for Girls, Adversity, Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, Segregation, Family Relationships, Sharon M. Draper, African American History Month, Ku Klux Klan, Cultural Wisdom, Books Set in the 1930s, Community Relationships, Add a tag

Stella by Starlight, by esteemed storyteller Sharon M. Draper, is a poignant novel that beautifully captures the depth and complexities within individuals, a community, and society in 1932, an era when segregation and poverty is at the forefront.

Add a CommentBlog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: History, Sociology, Politics, civil rights, America, North Carolina, KKK, *Featured, White supremacy, ku klux klan, David Cunningham, Bob Jones, Klansville, Klansville USA, Add a tag

American Experience asked sociologist and Ku Klux Klan scholar David Cunningham to provide responses to the five questions he is most frequently asked about the Klan. The author of Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era KKK, Cunningham is Professor and Chair of Sociology at Brandeis University.

Before discussing the most pressing questions people tend to have about the KKK, let me add some background for basic context. The Ku Klux Klan was first formed in 1866, through the efforts of a small band of Confederate veterans in Tennessee. Quickly expanding from a localized membership, the KKK has become perhaps the most resonant representation of white supremacy and racial terror in the United States. Part of the KKK’s enduring draw is that it refers not to a single organization, but rather to a collection of groups bound by use of now-iconic racist symbols — white hoods, flowing sheets, fiery crosses — and a predilection for vigilante violence. The Klan’s following has tended to rise and fall in cycles often referred to as “waves.” The original KKK incarnation was largely halted following federal legislation targeting Klan-perpetrated violence in the early 1870s. The Klan’s second — and largest — wave peaked in the 1920s, with KKK membership numbering in the millions. Following the second-wave Klan’s dissolution in the early 1940s, self-identified KKK groups also built sizable followings during the 1960s, in reaction to the rising Civil Rights Movement. Various incarnations have continued to mobilize since — often through blended affiliations with neo-Nazi, neo-Confederate, and Christian Identity organizations — but in small numbers and without significant impact on mainstream politics.

The American Experience documentary Klansville, U.S.A. focuses on the civil rights-era KKK and tells the story of Bob Jones, the most successful Klan organizer since World War II. Beginning in 1963, Jones took over the North Carolina leadership of the South’s preeminent KKK organization, the United Klans of America, and by 1965 his “Carolina Klan” boasted more than 10,000 members across the state, more than the rest of the South combined. Jones’ story illuminates our understanding of the KKK’s long history generally, and in particular provides a lens to consider the questions that follow.

How big a threat is the KKK in the United States today?

In an important sense, this may be the key question about the KKK and whether we should still worry, or care, about the Klan today. Likely for that reason, literally every discussion I’ve had about the Klan — whether in classrooms, community events, radio interviews, or cocktail parties — comes around to some version of this concern. I typically respond, in short, that a greater number of KKK organizations exist today than at any other point in the group’s long history, but that nearly all of these groups are small, marginal, and lacking in meaningful political or social influence.

I might add two caveats to that reassuring portrait, however. The first is that marginal, isolated extremist cells themselves can become breeding grounds for unpredictable violence. At the peak of his 1960s influence, Bob Jones would often tell reporters that, if they were truly concerned about violence perpetrated by Klan members, their greatest fear should be that he would disband the KKK, leaving individual members to commit mayhem free from the structure imposed by the group. As Jones’ followers committed hundreds of terrorist acts authorized by KKK leadership, his claim was of course disingenuous, but it also contained a grain of truth: Jones and his fellow leaders did dissuade members — many of whom combined rabid racism with unstable aggression — from engaging in violence not approved by the KKK hierarchy. In the absence of a broader organization with much to lose from a crack-down by authorities, racist violence can be much more difficult to prevent or police.

The second caveat stems from KKK’s history of emerging and receding in pronounced “waves.” Between the group’s periods of peak influence — say, during the 1880s, or in the 1940s, or the 1980s — the Klan’s fortunes have always appeared moribund. But in each case, some “reborn” version of the KKK has managed to rebound and survive. So, while today the KKK appears an anachronism and, perhaps, less of a threat than other brands of racist hate, we still should vigilantly oppose racist entrepreneurs who seek to exploit the historical cachet of the KKK to organize new campaigns advancing white supremacist ends. To me, this is one primary lesson from the KKK’s past, and a compelling reason not to forget or dismiss the enduring relevance of that history.

Has the KKK had any lasting political impact?

By most straightforward measures, the KKK appears a failed social movement. Despite the Klan’s political inroads during the 1920s, when millions of its members succeeded in electing hundreds of KKK-backed candidates to local, state, and even federal office, the group proved unable to preserve its influence at the ballot box beyond that decade. Later KKK waves have never been able to deliver on promises to rebuild this influential Klan voting bloc. Bob Jones’ Carolina Klan came the closest to winning such influence, with mainstream candidates currying favor (sometimes publicly, and more often covertly at Klan rallies and other events) with Jones and other leaders in 1964 and 1968. But that effort appeared short-lived, with both Jones and the Carolina Klan all but disappearing by the early 1970s.

More generally, the KKK’s commitment to white supremacy, most clearly realized through Jim Crow-style segregation that endured for decades in the South, has by any formal measure receded as a real possibility in the United States. However, in less overt ways, the KKK’s impact can still be felt. Recent studies that I’ve undertaken with fellow sociologists Rory McVeigh and Justin Farrell have demonstrated how counties in which the KKK was active during the 1960s differ from those in which the Klan never gained a foothold in two important ways.

First, counties in which the Klan was present during the civil rights era continue to exhibit higher rates of violent crime. This difference endures even 40 years after the movement itself disappeared, and certainly isn’t explained by the fact that former Klansmen themselves commit more crimes. Instead, the Klan’s impact operates more broadly, through the corrosive effect that organized vigilantism has on the overall community. By flouting law and order, a culture of vigilantism calls into question the legitimacy of established authorities and weakens bonds that normally serve to maintain respect and order among community members. Once fractured, such bonds are difficult to repair, which explains why even today we see elevated rates of violent crime in former KKK strongholds.

Second, past Klan presence also helps to explain the most significant shift in regional voting patterns since 1950: the South’s pronounced move toward the Republican Party. While support for Republican candidates has grown region-wide since the 1960s, we find that such shifts have been significantly more pronounced in areas in which the KKK was active. The Klan helped to produce this effect by encouraging voters to move away from Democratic candidates who were increasingly supporting civil rights reforms, and also by pushing racial conflicts to the fore and more clearly aligning those issues with party platforms. As a result, by the 1990s, racially-conservative attitudes among southerners strongly correlates with Republican support, but only in areas where the KKK had been active.

Is the KKK a movement mostly in the rural South?

While many of the Klan’s most infamous acts of deadly violence — including the 1964 Freedom Summer killings, the 1965 murder of civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo, and the 1981 lynching of Michael Donald that led to the 1987 lawsuit that ultimately put the United Klans of America out of business for good — occurred in the Deep South, during the 1920s the KKK was truly a national movement, with urban centers like Detroit, Portland, Denver, and Indianapolis boasting tens of thousands of members and significant political influence.

Even in the 1960s, when the KKK’s public persona seemed synonymous with Mississippi and Alabama, more dues-paying Klan members resided in North Carolina than the rest of the South combined. KKK leaders found the Tar Heel State fertile recruiting ground, despite — or perhaps because of — the state’s progressive image, which enabled the Klan to claim that they were the only group that would defend white North Carolinians against rising civil rights pressures. While this message resonated in rural areas across the state’s eastern coastal plain, the KKK built a significant following in cities like Greensboro and Raleigh as well.

Today, the Southern Poverty Law Center reports active KKK groups in 41 states, though nearly all of those groups remain marginal with tiny memberships. So, while the KKK originated after the Civil War as a distinctly southern effort to preserve the antebellum racial order, its presence has extended well beyond that region throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Why do KKK members wear white hoods and burn crosses?

Some of the most recognizable Klan symbols date back to the group’s origins following the Civil War. The KKK’s white hoods and robes evolved from early efforts to pose as ghosts or “spectral” figures, drawing on then-resonant symbols in folklore to play “pranks” against African-Americans and others. Such tricks quickly took on more politically sinister overtones, as sheeted Klansmen would commonly terrorize their targets, using hoods and masks to disguise their identities when carrying out acts of violence under the cover of darkness.

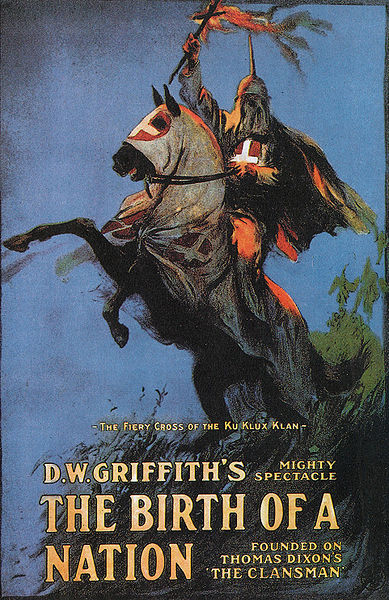

Fiery crosses, perhaps the Klan’s most resonant symbol, have a more surprising history. No documented cross burnings occurred during the first Klan wave in the 19th century. However, D.W. Griffith’s epic 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, which adapted Thomas F. Dixon, Jr.’s novels The Clansman and The Leopard’s Spots to portray the KKK as heroic defenders of the Old South and white womanhood generally, drew on material from The Clansman to depict a cross-burning scene. The symbol was quickly appropriated by opportunistic KKK leaders to help spur the group’s subsequent “rebirth.”

Through the 1960s, Klan leaders regularly depicted the cross as embodying the KKK’s Christian roots — a means to spread the light of Jesus into the countryside. A bestselling 45rpm record put out by United Klans of America included the Carolina Klan’s Bob Jones reciting how the fiery cross served as a “symbol of sacrifice and service, and a sign of the Christian Religion sanctified and made holy nearly 19 centuries ago, by the suffering and blood of 50 million martyrs who died in the most holy faith.” He emphasized cross burnings as “driv[ing] away darkness and gloom… by the fire of the Cross we mean to purify and cleanse our virtues by the fire on His Sword.” Such grandiose rhetoric, of course, could not dispel the reality that the KKK frequently deployed burning crosses as a means of terror and intimidation, and also as a spectacle to draw supporters and curious onlookers to their nightly rallies, which always climaxed with the ritualized burning of a cross that often extended 60 or 70 feet into the sky.

Has the KKK always functioned as a violent terrorist group?

The KKK’s emphasis on violence and intimidation as a means to defend its white supremacist ends has been the primary constant across its various “waves.” Given the group’s brutal history, validating Klan apologists who minimize the group’s terroristic legacy makes little sense. However, during the periods of peak KKK successes in both the 1920s and 1960s, when Klan organizations were often significant presences in many communities, their appeal was predicated on connecting the KKK to varied aspects of members’ and supporters’ lives.

Such efforts meant that, in the 1920s, alongside the KKK’s political campaigns, members also marched in parades with Klan floats, pursued civic campaigns to support temperance, public education, and child welfare, and hosted a range of social events alongside women’s and youth Klan auxiliary groups. Similarly, during the civil rights era, many were drawn to the KKK’s militance, but also to leaders’ promises to offer members “racially pure” weekend fish frys, turkey shoots, dances, and life insurance plans. In this sense, the Klan served as an “authentically white” social and civic outlet, seeking to insulate members from a changing broader world.

The Klan’s undoing in both of these eras related in part to Klan leaders’ inability to maintain the delicate balancing act between such civic and social initiatives and the group’s association with violence and racial terror. Indeed, in the absence of the latter, the Klan’s emphasis on secrecy and ritual would have lost much of its nefarious mystique, but KKK-style lawlessness frequently went hand-in-hand with corruption among its own leaders. More importantly, Klan violence also often resulted in a backlash against the group, both from authorities and among the broader public.

This article first appeared on PBS American Experience.

Heading image: Altar with K eagle in black robe at a meeting of nearly 30,000 Ku Klux Klan members from Chicago and northern Illinois. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Ku Klux Klan in history and today appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: American Experience, *Featured, White supremacy, Images & Slideshows, ku klux klan, David Cunningham, Bob Jones, Klansville, United Klans of America, PBS, History, Politics, american history, civil rights, America, North Carolina, usa, KKK, Add a tag

In the 1960s, the South, was rife with racial tension. The Supreme Court had just declared, in its landmark case Brown vs. Board of Education, that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, and the country was in the midst of a growing Civil Rights Movement. In response to these events, Ku Klux Klan activity boomed, reaching an intensity not seen since the 20s, when they boasted over four million members. Surprisingly, North Carolina, which had been one of the more progressive Southern states, had the largest and most active Klan membership — greater than the rest of the South combined — earning it the nickname “Klansville, USA”. This slideshow features images from the time of the Civil Rights-era Klan.

Be sure to check out the American Experience documentary Klansville U.S.A. airing Tuesday, 13 January on PBS.

Heading image: The Ku Klux Klan on parade down Pennsylvania Avenue, 1928. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Civil Rights era and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: movies, film, hollywood, Racism, silent film, Lincoln, civil war, Cullen, cinema, *Featured, american cinema, D.W. Griffith, TV & Film, ku klux klan, Spielberg, Arts & Leisure, Birth of a Nation, Jim Cullen, Sensing the Past, griffith, griffith’s, Add a tag

By Jim Cullen

Today represents a red letter day — and a black mark – for US cultural history. Exactly 98 years ago, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation premiered in Los Angeles. American cinema has been decisively shaped, and shadowed, by the massive legacy of this film.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

The source material for Birth of a Nation came from two novels, The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden (1902) and The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), both written by Griffith’s Johns Hopkins classmate, Thomas Dixon. Dixon drew on the common-sense version of history he imbibed from his unreconstructed Confederate forebears. According to this master narrative, the Civil War was as a gallant but failed bid for independence, followed by vindictive Yankee occupation and eventual redemption secured with the help of organizations like the Klan.

But Dixon’s fiction, and the subsequent screenplay (by Griffith and Frank E. Woods), was a literal and figurative romance of reconciliation. The movie dramatizes the relationships between two (related) families, the Camerons of South Carolina and the Stonemans of Pennsylvania. The evil patriarch of the latter is Austin Stoneman, a Congressman with a limp very obviously patterned on the real-life Thaddeus Stevens. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Stevens comes, Carpetbagger-style, and uses a brutish black minion, Silas Lynch(!), whose horrifying sexual machinations focused, ironically and naturally, on Stoneman’s own daughter are only arrested by at the last minute, thanks to the arrival of the Klan in a dramatic finale that has lost none of its excitement even in an age of computer-generated imagery.

Historians agree that Griffith, a former actor who directed hundreds of short films in the years preceding Birth of a Nation, was not a cinematic pioneer along the lines of Edwin S. Porter, whose 1903 proto-Western The Great Train Robbery virtually invented modern visual grammar. Instead, Griffith’s genius was three-fold. First, he absorbed and codified a series of techniques, among them close-ups, fadeouts, and long shots, into a distinctive visual signature. Second, he boldly made Birth of a Nation on an unprecedented scale in terms of length, the size of the production, and his ambition to re-create past events (“history with lightning,” in the words of another classmate, Woodrow Wilson, who screened the film at the White House). Finally, in the way the movie was financed, released and promoted, Griffith transformed what had been a disreputable working-class medium and staked its power as a source of genuine artistic achievement. Even now, it’s hard not to be awed by the intensity of Griffith’s recreation of Civil War battles or his re-enactments of events like the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

But Birth of a Nation was a source of instant controversy. Griffith may have thought he was simply projecting common sense, but a broad national audience, some of which had lived through the Civil War, did not necessarily agree. The film’s release also coincided with the beginnings of African American political mobilization. As Melvyn Stokes shows in his elegant 2009 book D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the film’s promoters and its critics alike found the controversy surrounding it curiously symbiotic, as moviegoers flocked to see what the fuss was about and the fledgling National Association for the Advancement of Colored People used the film’s notoriety to build its membership ranks.

Birth of a Nation never escaped from the original shadows that clouded its reception. Later films like Gone with the Wind (1939), which shared much of its political outlook, nevertheless went to great lengths to sidestep controversy. (The Klan is only alluded to as “a political meeting” rather than depicted the way it was in Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel.) Today Birth is largely an academic curio, typically viewed in settings where its racism looms over any aesthetic or other assessment.

In a number of respects, Steven Spielberg’s new film Lincoln is a repudiation of Griffith. In Birth, Lincoln is a martyr whose gentle approach to his adversaries is tragically severed with his death. But in Lincoln he’s the determined champion of emancipation, willing to prosecute the war fully until freedom is secure. The Stevens character of Lincoln, played by Tommy Lee Jones, is not quite the hero. But his radical abolitionism is at least respected, and the very thing that tarred him in Birth — having a secret black mistress — here becomes a badge of honor. Rarely do the rhythms of history oscillate so sharply. Griffith would no doubt be bemused. But he could take such satisfaction in the way his work has reverberated across time.

For Jim Cullen’s selection of films all history and film buffs should see, watch his video syllabus.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jim Cullen teaches history at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City. He is the author of Sensing the Past: Hollywood Stars and Historical Visions (December 2012), The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation, and other books. Cullen is also a book review editor at the History News Network. Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only TV and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Birth of a Nation film poster, 1915, public domain in Wikimedia Commons.

The post The strange career of Birth of a Nation appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: American Experience, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, bloody sunday, *Featured, freedom rides, racial justice, ray arsenault, whites only, ku klux klan, slave market, PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, birmingham, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, KKK, massacre, college students, scottsboro, NAACP, Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 6–May 13: Nashville, TN, to Birmingham, AL

Day 6 started with a torrential downpour–the first bad weather of the trip–that prevented us from walking around the Fisk campus and touring Jubilee Hall and the chapel. So we headed south for Birmingham, passing through Giles County, the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, and by Decatur, AL, the site of the 1932 Scottsboro trial. We arrived in Birmingham in time for lunch at the Alabama Power Company building, a corporate fortress symbolic of the “new” Birmingham. We spent the afternoon at the magnificent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where we were met by Freedom Riders Jim Zwerg and Catherine Burks Brooks, and by Odessa Woolfolk, the guiding force behind the Institute in its early years. Catherine treated the students to a rollicking memoir of her life in Birmingham, and Odessa followed with a moving account of her years as a teacher in Birmingham and a discussion of the role of women in the civil rights movement. Odessa is always wonderful, but she was particularly warm and humane today. We then went across the street for a tour of the 16th Street Baptist Church, the site of the September 1963 bombing that killed the “four little girls.”

The rest of the afternoon was dedicated to a tour of the Institute; there is never enough time to do justice to the Institute’s civil rights timeline, but this visit was much too brief, I am afraid. Seeing the Freedom Rider section with the Riders, especially Jim Zwerg and Charles Person who had searing experiences in Birmingham in 1961, was highly emotional for me, for them, and for the students. As soon as the Institute closed, we retired to the community room for a memorable barbecue feast catered by Dreamland Barbecue, the best in the business. We then went back across the street to 16th Street for a freedom song concert in the sanctuary. The voices o