new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Mexican-American War, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 3 of 3

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Mexican-American War in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: AlyssaB,

on 4/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

mexico,

America,

Humanities,

religion in america,

*Featured,

Mexican-American War,

patricios,

pinheiro,

Add a tag

By John C. Pinheiro

Few Americans today would have difficulty imagining a United States where the citizens disagree over the wisdom of immigration, question the degree to which Mexicans can be fully American, and dispute about the value of religious pluralism. But what if the America in question was not that of 2014 but rather the 1830s and 1840s? Along with being a high point of anti-Catholic nativism, these two decades witnessed the Texas Revolution, the US annexation of Texas, violence in US cities against Catholic immigrants, and the Mexican-American War. As Americans struggled to negotiate their identity as a people in terms of race, religion, and political culture, the war with Mexico clarified and for one century afterward cemented American identity as a Protestant, Anglo-Saxon republic.

Manifest Destiny held that American Anglo-Saxons, by reason of their cultural and racial superiority, were destined to overtake the western hemisphere. This Anglo-Saxonism was not so much based on attributes like skin color, as it was on unique attitudinal traits that predisposed Anglo-Saxons to be the most effective guardians of liberty. From this innate love of freedom had sprung Protestantism and republicanism—the religion and government for free men.

While the majority of Americans condemned a series of mob attacks against Catholic convents, churches, and schools in Boston and in Philadelphia, they nevertheless agreed with nativists that Catholicism was incompatible with representative—or what they called, “republican”—government. Politically unstable Mexico, they said, was proof of this.

When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, doubts quickly surfaced about the patriotic fortitude of foreign-born, Irish-Americans in a war against a Catholic nation. Irish immigrant soldier John Riley fled the US army on 12 April 1846, about two weeks before the first battle of the war. American authorities suspected that in September 1846 he was the leader of a group of mostly Irish and Catholic deserters at the Battle of Monterey. These rumors were true, and in late 1847 the US Army captured the San Patricios, or Saint Patrick Battalion. In the United States, debate ensued over the San Patricios’ motives and goals. At stake was the question of immigrant Catholic loyalty to the United States.

So, what were the factors in the San Patricio desertion? Abuse by nativist American officers was one of them. For a given crime, officers would sometimes merely demote native-born soldiers while imprisoning, whipping, or dishonorably discharging foreign-born men. Atrocities, church looting, and violence against priests by some American troops aggravated the fear that the Protestant United States was attacking not just Mexico but the Catholic faith.

The causes of this desertion, however, were not a one-sided affair. Mexican propaganda enticed Americans to leave their ranks. One broadside was addressed to “Catholic Irishmen” by General Antonio López de Santa Anna but the writer probably was Riley. It beckoned Americans to “Come over to us; you will be received under the laws of that truly Christian hospitality and good faith which Irish guests are entitled to expect and obtain from a Catholic nation.” It then asked, “Is religion no longer the strongest of all human bonds? Can you fight by the side of those who put fire to your temples in Boston and Philadelphia”?

It is most accurate, then, to say that while religion was involved in the defection, most of the San Patricios deserted because of intense abuse by officers, not for love of Mexico or the Catholic Church. This includes Riley. In all, 27 San Patricios were hanged.

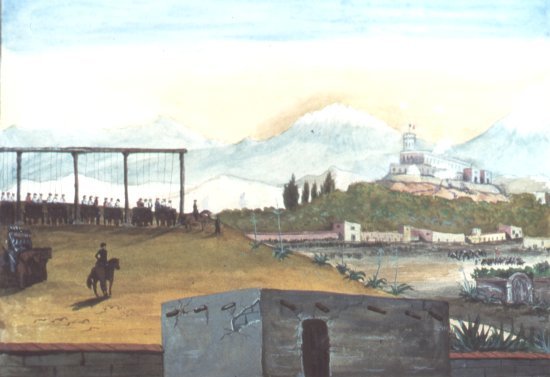

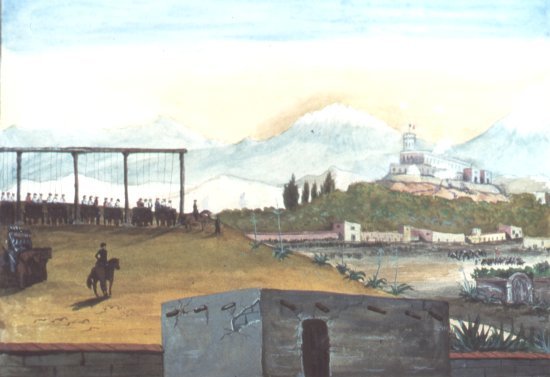

Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec. Painted in the 1840s by Sam Chamberlain. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The capture and punishment of the San Patricios may have been dramatic, but the questioning of Catholic loyalty was just one small part of religion’s interplay with the war. Religious rhetoric constituted an integral piece of nearly every major argument for or against the war. This civil religious discourse was so universally understood that recruiters, politicians, diplomats, journalists, soldiers, evangelical activists, abolitionists, and pacifists used it. It helped shape everything from debates over annexation to the treatment of enemy soldiers and civilians. Religion also was the primary tool used by Americans to interpret Mexico’s fascinating but alien culture.

More than any other event during the nineteenth century, the Mexican-American War clarified the anti-Catholic assumptions inherent to American identity. At the same time, from the crucible of war emerged an American civil religion that can only be described as a triumphalist Protestant and white, anti-Catholic republicanism. That civil religion lasted well into the twentieth century. The degree to which it is still alive today in current debates over Latino immigration is debatable, but one can hardly miss the resemblance and connection between the issues of the 1840s and those of 2014.

John C. Pinheiro is Associate Professor of History at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He has written two books on the Mexican-American War. His newest book is Missionaries of Republicanism: A Religious History of the Mexican-American War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Mexican-American War and the making of American identity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: JonathanK,

on 2/2/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

US,

Oxford,

mexico,

Current Affairs,

immigration,

Geography,

border,

Berlin Wall,

Tijuana,

*Featured,

Mexican-American War,

Guadalupe Hidalgo,

Michael Dear,

Polk,

Third Nation,

nafta,

Add a tag

By Michael Dear

Not long ago, I passed a roadside sign in New Mexico which read: “Es una frontera, no una barrera / It’s a border, not a barrier.” This got me thinking about the nature of the international boundary line separating the US from Mexico. The sign’s message seemed accurate, but what exactly did it mean?

On 2 February 1848, a ‘Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement’ was signed at Guadalupe Hidalgo, thus terminating the Mexican-American War. The conflict was ostensibly about securing the boundary of the recently-annexed state of Texas, but it was clear from the outset that US President Polk’s ambition was territorial expansion. As consequences of the Treaty, Mexico gained peace and $15 million, but eventually lost one-half of its territory; the US achieved the largest land grab in its history through a war that many (including Ulysses S. Grant) regarded as dishonorable.

In recent years, I’ve traveled the entire length of the 2,000-mile US-Mexico border many times, on both sides. There are so many unexpected and inspiring places! Mutual interdependence has always been the hallmark of cross-border communities. Border people are staunchly independent and composed of many cultures with mixed loyalties. They get along perfectly well with people on the other side, but remain distrustful of far-distant national capitals. The border states are among the fastest-growing regions in both countries — places of economic dynamism, teeming contradiction, and vibrant political and cultural change.

A small fence separates densely populated Tijuana, Mexico, right, from the United States in the Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector.

Yet the border is also a place of enormous tension associated with undocumented migration and drug wars. Neither of these problems has its source in the borderlands, but border communities are where the burdens of enforcement are geographically concentrated. It’s because of our country’s obsession with security, immigration, and drugs that after 9/11 the US built massive fortifications between the two nations, and in so doing, threatened the well-being of cross-border communities.

I call the spaces between Mexico and the US a ‘third nation.’ It’s not a sovereign state, I realize, but it contains many of the elements that would otherwise warrant that title, such as a shared identity, common history, and joint traditions. Border dwellers on both sides readily assert that they have more in common with each other than with their host nations. People describe themselves as ‘transborder citizens.’ One man who crossed daily, living and working on both sides, told me: “I forget which side of the border I’m on.” The boundary line is a connective membrane, not a separation. It’s easy to reimagine these bi-national communities as a ‘third nation’ slotted snugly in the space between two countries. (The existing Tohono O’Odham Indian Nation already extends across the borderline in the states of Arizona and Sonora.)

But there is more to the third nation than a cognitive awareness. Both sides are also deeply connected through trade, family, leisure, shopping, culture, and legal connections. Border-dwellers’ lives are intimately connected by their everyday material lives, and buttressed by innumerable formal and informal institutional arrangements (NAFTA, for example, as well as water and environmental conservation agreements). Continuity and connectivity across the border line existed for centuries before the border was put in place, even back to the Spanish colonial era and prehistoric Mesoamerican times.

Do the new fortifications built by the US government since 9/11 pose a threat to the well-being of borderland communities? Certainly there’s been interruptions to cross-border lives: crossing times have increased; the number of US Border Patrol ‘boots on ground’ has doubled; and a new ‘gulag’ of detention centers has been instituted to apprehend, prosecute and deport all undocumented migrants. But trade has continued to increase, and cross-border lives are undiminished. US governments are opening up new and expanded border crossing facilities (known as ports of entry) at record levels. Gas prices in Mexican border towns are tied to the cost of gasoline on the other side. The third nation is essential to the prosperity of both countries.

So yes, the roadside sign in New Mexico was correct. The line between Mexico and the US is a border in the geopolitical sense, but it is submerged by communities that do not regard it as a barrier to centuries-old cross-border intercourse. The international boundary line is only just over a century-and-a-half old. Historically, there was no barrier; and the border is not a barrier nowadays.

The walls between Mexico and the US will come down. Walls always do. The Berlin Wall was torn down virtually overnight, its fragments sold as souvenirs of a calamitous Cold War. The Great Wall of China was transformed into a global tourist attraction. Left untended, the US-Mexico Wall will collapse under the combined assault of avid recyclers, souvenir hunters, and local residents offended by its mere presence.

As the US prepares once again to consider immigration reform, let the focus this time be on immigration and integration. The framers of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were charged with making the US-Mexico border, but on this anniversary of the Treaty’s signing, we may best honor the past by exploring a future when the border no longer exists. Learning from the lives of cross-border communities in the third nation would be an appropriate place to begin.

Michael Dear is a professor in the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Why Walls Won’t Work: Repairing the US-Mexico Divide (Oxford University Press).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “Third Nation” along the US-Mexico border appeared first on OUPblog.

by Rudy Ch. Garcia

by Rudy Ch. Garcia

The San Patricios Brigade is one of my favorite topics in bars and classrooms. On St. Patrick's Days I've asked bar patrons who were celebrating St. Pat's with beers if they knew about La Brigada; in all of my years of polling, only one red-haired American ever did. The majority of the others didn't look pleased nor thank me for filling out their historical ignorance about a period of their homeland's shameful past.

And each Sept. in my primary classrooms I've introduced the history of the Irish immigrants who fought on the side of Mexico in the War to Steal the SW from Underdeveloped Mexico. It quickly made my students more historically aware than most Anglo American adults. About their own country's history. The children were always greatly affected, by the brutality perpetrated against those white immigrants and by their solidarity with their Mexican ancestors.

It doesn't seem ironic to me that Hispanic Hispanic Heritage Month in this country, officially celebrated from Sept 15-Oct.15. doesn'tcoincide with Mexico's annual recognition of The San Patricio Brigade earlier in Sept. It seems in keeping with typical American denial of dismal historical crimes.

After my reading/singing of my fantasy novel at the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque* will follow a special event. La Bloga has written before about this event that is greatly celebrated in Mexico and Ireland. In this past post two significant books were reviewed, Irish Soldiers of Mexico and Molly Malone and the San Patricios, that describe the events leading to the torture, beatings, brandings and hangings of those Irish-American heroes. You can read additional background info from The Society for Irish Latin American.Studies, among others.

As important to read about and contemplate as Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, it's something every American should know, not just those of us of Spanish-speaking heritage or seven-year-old Mexican immirgrant children, or those in Ireland or Mexico. Below is the information from NHCC on the Albuquerque commemoration:

El Día de los San Patricios

Saturday, September 29th at 4:00 pm

Wells Fargo Auditorium

National Hispanic Cultural Center

Free Admission

For the third year, the NHCC commemorates the courage of the St. Patrick’s Battalion whose soldiers fought for Mexico, forging strong ties between Ireland and Mexico that continue to this day. During the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, more than five hundred immigrant soldiers, mostly Irish, deserted the U.S. Army and joined forces with Mexico. These men became known as the San Patricios. Every year this event is commemorated in Mexico and in Ireland at the highest levels of government.

For the third year, the NHCC commemorates the courage of the St. Patrick’s Battalion whose soldiers fought for Mexico, forging strong ties between Ireland and Mexico that continue to this day. During the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, more than five hundred immigrant soldiers, mostly Irish, deserted the U.S. Army and joined forces with Mexico. These men became known as the San Patricios. Every year this event is commemorated in Mexico and in Ireland at the highest levels of government.

A lecture by UNM Professor Caleb Richardson, live music by Gerry Muissener and Chuy Martinez and a screening of The San Patricios: the Tragic Story of the St. Patrick’s Battalion, a video documentary by Mark Day will be offered to the public free of charge by the National Hispanic Cultural Center in the Wells Fargo Auditorium on Saturday Sept. 29th at 4 PM.

Dr. Caleb Richardson is an expert on Irish, British, and European history and will give his perspective on the reasons for the formation of the St. Patrick’s Battalion during the U.S.-Mexican War. Gerry Muissener of the Irish American Society will perform live music as will Chuy Martinez of Los Trinos.

Commenting on the Mark Day film, historian Howard Zinn said, “Absolutely enthralling. Dynamite material. It is a perfect example of historical amnesia in America that this story is virtually unknown to every American. A superb job.” Howard Zinn author of A People’s History of the United States. For more information, call Greta Pullen at 505-724-4752 or Laura Bonar at 505-352-1236.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

* LaBloga-ero Rudy Ch. Garcia will do a reading & signing of his Chicano fantasy novel tomorrow Sat. Sept. 29th at 2:00pm in the National Hispanic Cultural Center, 1701 4th St. SW, in Albuquerque. Please inform anyone in that area that you think might be interested. The Closet of Discarded Dreams on sale for $16. (NHCC contact Greta Pullen 505-724-4752)