‘Public Servant’ — in the sense of ‘government employee’ — is a term that originated in the earliest days of the European settlement of Australia. This coinage is surely emblematic of how large bureaucracy looms in Australia. Bureaucracy, it has been well said, is Australia’s great ‘talent,’ and “the gift is exercised on a massive scale” (Australian Democracy, A.F. Davies 1958). This may surprise you. It surprises visitors, and excruciates them.

The post Australia in three words, part 3 — “Public servant” appeared first on OUPblog.

By Geordan Hammond

The ideal of primitivism was common feature in eighteenth-century British society whether in architecture, art, economics, landscape gardening, literature, music, or religion. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s six London neo-classical churches are one example of the primivitist ideal in architecture and religion.

Primitivism featured prominently in the plans the Georgia Trustees in the founding of the last of the thirten American colonies in 1732. The Trustees, who governed Georgia for its first twenty years, chose the motto Non sibi sed aliis (Not for self, but for others) for their official seal. This in itself was an indication of their attraction to primitivism as the Latin phrase was derived from the closing words of St Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine).

The motto also helped the Trustees to express the philanthropic intention at the heart of their establishment of Georgia. This slogan interpreted within the context of the eighteenth-century economic debates on trade and luxury, illustrates the Trustees’ appeal to a traditional classical notion of virtue. And it was in their economic ideals for the new colony that the Trustees’ appeal to primitivism can be seen most clearly.

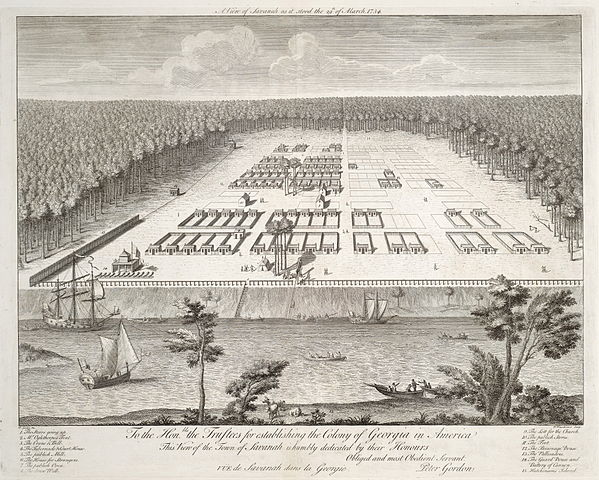

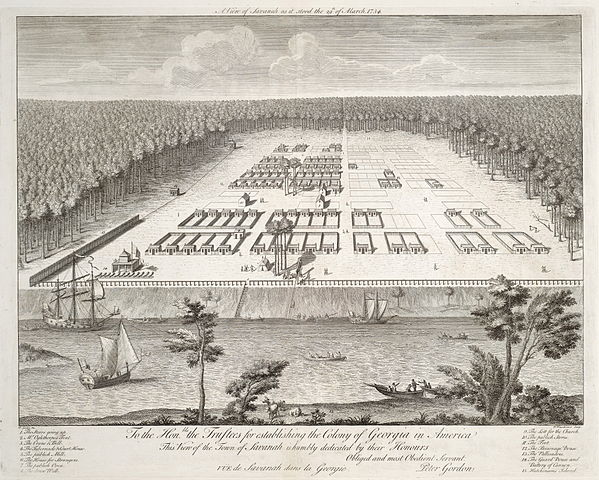

A view of Savannah as it stood the 29th of March 1734. By Pierre Fourdrinier and James Oglethorpe. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The ideal of disinterested charity was enshrined in the colony’s charter which prevented the Trustees “and their Successors from receiving any Salary, Fee, Perquisite, or Profit whatsoever by or from this undertaking.” The Trustees’ philosophy of disinterested charity was intimately bound up with their overarching ideal of economic primitivism. Much of the promotional literature for the Georgia colony appealed to the primitivist ideal widely espoused in eighteenth-century Britain, especially by Tory opposition to the Walpole government. The opposition polemic advocated a return to a mythical age when all people worked together primarily for the good of the community rather than for their own prosperity.

The Georgia colony was designed to avoid the twin dangers of luxury and idleness through a return to primitive community based economic life. For the Trustees, this was exemplified by the proper balance between moral and economic development achieved in ancient Rome. Though in obvious conflict with the reality of life in ancient Rome, the Trustees prohibited rum, slavery, and large landholdings with the aim of restoring ancient virtue. They believed that proper social restraints needed to be in place in order to militate against vice and encourage civic responsibility. By critiquing British luxury, the Georgia colony was intended to be an example of a more pure and primitive form of community oriented economic life.

This was all undergirded by a clear religious motive. For the Trustees, economic primitivism, as a means of imitating Christ, was conceived of as an expression of their Christian faith. Their desire was for Georgia to be a religious utopia modelled on the ideal of reviving a lost age of primitive Christian virtue. Toward this aspiration they sought divine blessing on their endeavours by implementing notions of economic biblical communitarianism. They also consciously modelled the town plan of Savannah on biblical and classical patterns.

Was the Trustees’ vision achievable? Was it doomed to fail when brought into contact with the realities of a colony in an undeveloped primitive wilderness? While often sympathizing with the Trustees’ ideals, many historians of colonial Georgia have answered the latter question in the affirmative. For example, the Trustees’ determination to manage social life in Georgia combined with their distrust of the colonists’ ability to govern themselves led to weak and often ineffective social structures such as the dysfunctional court which habitually became a centre of conflict when de facto governor James Oglethorpe was absent from the colony.

The Trustees’ idealistic policies, in part, led a loose group they labelled ‘malcontents’ to advocate for the reversal of the banns on rum, slavery, and large landholdings which were central to the Trustees’ hopes of moulding Georgia into a primitive utopia. In A True and Historical Narrative of the Colony of Georgia in America (1741) discontented colonists mocked the Trustees for giving them “the opportunity of arriving at the integrity of the Primitive Times, by entailing a more than Primitive Poverty on us … As we have no Properties to feed Vain-Glory and beget Contention.” Over time the Trustees grudgingly gave up on their prohibitions of rum, slavery, and large landholdings.

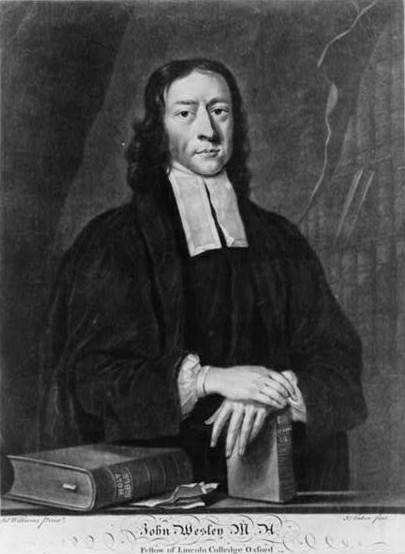

In the midst of the conflict between the Trustees’ lofty ideals and the realities of life in early Georgia, John Wesley, the co-founder of Methodism, arrived in the colony in 1736. Wesley himself was a primitivist of a slightly different order than the Trustees. Having spent much of the last fifteen years in the academic surroundings of Oxford, Wesley arrived in Georgia with a burning passion to restore the doctrine, discipline, and practice of the primitive church in the primitive Georgia wilderness.

While his motivation was primarily religious, and was driven by a High Church Anglican ideal, he sympathized with the Trustees’ economic primitivism. The authors of A True and Historical Narrative claimed that he “frequently declared, that he never desired to see Georgia a Rich, but a Religious Colony.” Ironically, however, in the minds of some Trustees, Wesley became a ‘malcontent’ who undermined their authority by becoming an advocate for poor colonists whom he believed were being oppressed by the magistrates and court in Savannah.

The early years of colonial Georgia provide a fascinating case study to observe attempts to apply the eighteenth-century British cultural phenomenon of primitivism in a primitive environment.

Geordan Hammond is Senior Lecturer in Church History and Wesley Studies at the Nazarene Theological College, Manchester, UK. He is the author of John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity. He is co-organizer of the June 2014 ‘George Whitefield at 300′ conference. He serves as co-editor of the journal Wesley and Methodist Studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The appeal of primitivism in British Georgia appeared first on OUPblog.

By Stephen Foster

Finishing a book is a burden lifted accompanied by a sense of loss. At least it is for some. Academic authors, stalked by the REF in Britain and assorted performance metrics in the United States, have little time these days for either emotion. For emeriti, however, there is still a moment for reflecting upon the newly completed work in context—what were it origins, what might it contribute, how does it fit in? The answer to this last query for an historian of colonial America with a collateral interest in Britain of the same period is “oddly.” Somehow the renascence of interest in the British Empire has managed to coincide with a decline in commitment in the American academy to the history of Great Britain itself. The paradox is more apparent than real, but dissolving it simply uncovers further paradoxes nested within each other like so many homunculi.

Begin with the obvious. If Britain is no longer the jumping off point for American history, then at least its Empire retains a residual interest thanks to a supra-national framework, (mostly inadvertent) multiculturalism, and numerous instances of (white) men behaving badly. The Imperial tail can wag the metropolitan dog. But why this loss of centrality in the first place? The answer is also supposed to be obvious. Dramatic changes, actual and projected, in the racial composition of late twentieth and early twenty-first century America require that greater attention be paid to the pasts of non-European cultures. Members of such cultures have in fact been in North America all along, particularly the indigenous populations of North America at the time of European colonization and the African populations transported there to do the heavy work of “settlement.” Both are underrepresented in the traditional narratives. There are glaring imbalances to be redressed and old debts to be settled retroactively. More Africa, therefore, more “indigeneity,” less “East Coast history,” less things British or European generally.

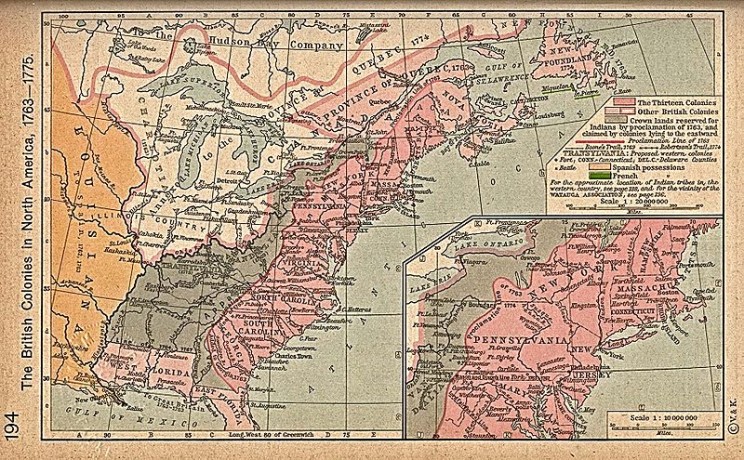

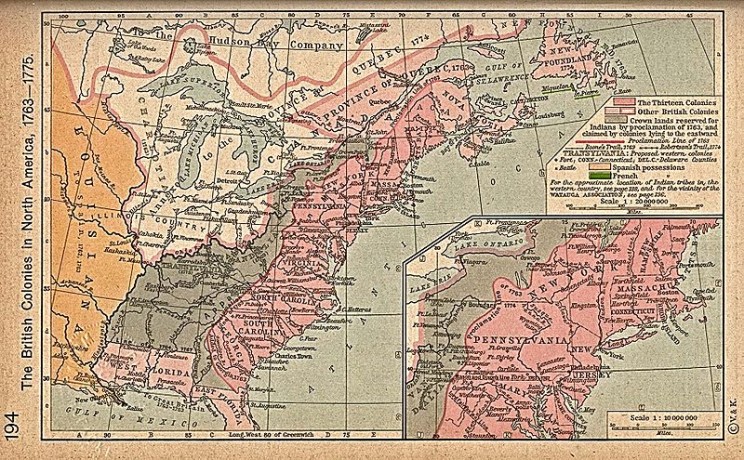

The British Colonies in North America 1763 to 1776

The all but official explanation has its merits, but as it now stands it has no good account of how exactly the respective changes in public consciousness and academic specialization are correlated. Mexico and people of Mexican origin, for example, certainly enjoy a heightened salience in the United States, but it rarely gets beyond what in the nineteenth century would have been called The Mexican Question (illegal immigration, drug wars, bilingualism). Far more people in America can identify David Cameron or Tony Blair than Enrique Peña Nieto or even Vincente Fox. As for the heroic period of modern Mexican history, its Revolution, it was far better known in the youth of the author of this blog (born 1942), when it was still within living memory, than it is at present. That conception was partial and romantic, just as the popular notion of the American Revolution was and is, but at least there was then a misconception to correct and an existing interest to build upon.

One could make very similar points about the lack of any great efflorescence in the study of the Indian Subcontinent or the stagnation of interest in Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War despite the increasing visibility of individuals from both regions in contemporary America. Perhaps the greatest incongruity of all, however, is the state of historiography for the period when British and American history come closest to overlapping. In the public mind Gloriana still reigns: the exhibitions, fixed and traveling, on the four hundredth anniversary of the death of Elizabeth I drew large audiences, and Henry VIII (unlike Richard III or Macbeth) is one play of Shakespeare’s that will not be staged with a contemporary America setting. The colonies of early modern Britain are another matter. In recent years whole issues of the leading journal in the field of early American history have appeared without any articles that focus on the British mainland colonies, and one number on a transnational theme carries no article on either the mainland or a British colony other than Canada in the nineteenth century. Although no one cares to admit it, there is a growing cacophony in early American historiography over what is comprehended by early and American and, for that matter, history. The present dispensation (or lack thereof) in such areas as American Indian history and the history of slavery has seen real and on more than one occasion remarkable gains. These have come, however, at a cost. Early Americanists no longer have a coherent sense of what they should be talking about or—a matter of equal or greater significance–whom they should be addressing.

Historians need not be the purveyors of usable pasts to customers preoccupied with very narrow slices of the present. But for reasons of principle and prudence alike they are in no position to entirely ignore the predilections and preconceptions of educated publics who are not quite so educated as they would like them to be. In the world’s most perfect university an increase in interest in, say, Latin America would not have to be accompanied by a decrease in the study of European countries except in so far as they once possessed an India or a Haiti. In the current reality of rationed resources this ideal has to be tempered with a dose of “either/or,” considered compromises in which some portion of the past the general public holds dear gives way to what is not so well explored as it needs to be. Instead, there seems instead to be an implicit, unexamined indifference to an existing public that knows something, is eager to know more, and, therefore, can learn to know better. Should this situation continue, outside an ever more introverted Academy the variegated publics of the future may well have no past at all.

Stephen Foster is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus (History), Northern Illinois University. His most recent publication is the edited volume British North America in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The British Colonies 1763 to 1776. By William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Declaration of independence appeared first on OUPblog.