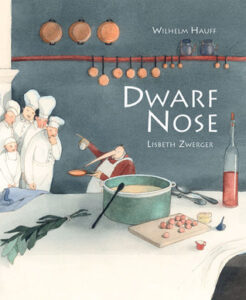

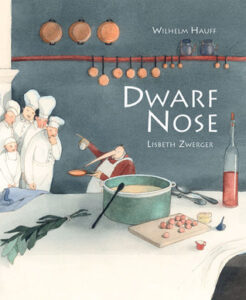

Dwarf Nose

Dwarf Nose

By Wilhelm Hauff

Illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger

Translated by Anthea Bell

Minedition

$19.99

ISBN: 97898888341139

Ages 8-12

On shelves April 1st

It seems so funny to me that for all that our culture loves and adores fairytales, scant attention is paid to the ones that can rightfully be called both awesome and obscure. There is a perception out there that there are only so many fairytales out there that people really need to know. But for every Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty you run into, there’s a Tatterhood or Riquet with the Tuft lurking on the sidelines. Thirty or forty years ago you’d sometimes see these books given a life of their own front and center with imaginative picture book retellings. No longer. Folktales and fairytales are widely viewed by book publishers as a dying breed. A great gaping hole exists, and into it the smaller publishers of the world have sought to fulfill this need. Generally speaking they do a very good job of bringing world folktales to the American marketplace. Obscure European fairytales, however, are rare beasts. How thrilled I was then to discover the republication of Wilhelm Hauff and Lisbeth Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose. Originally released in America in 1995 by North-South books, the book has long been out-of-print. Now the publisher minedition has brought it back and what a beauty it is. Strange and sad and oddly uplifting, this tale has all the trappings of the fairytales you know and love, but somehow remains entirely unexpected just the same.

For there once was a boy who lived with his two adoring parents. His father was a cobbler and his mother sold vegetables and herbs in the market. One day the boy was assisting his mother when a very strange old woman came to them and starting digging her dirty old hands through their wares. Incensed, the boy insulted the old woman, which as you may imagine didn’t go down very well. When the boy is made to help carry the woman’s purchases back to her home he is turned almost immediately into a squirrel and made to work for seven years in her kitchen. After that time he awakes, as if in a dream, only to find seven years have passed and his body has been transformed. Now he has no neck to speak of, a short frame, a hunched back, and a extraordinarily long nose. Sad that his parents refuse to acknowledge him as their son, he sets forth to become the king’s cook. And all would have gone without incident had he not picked up that enchanted goose in the market one day. Written in 1827 this tale is famous in Germany but remains relatively obscure in the United States today.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

We like it when our fairytales give us nice clear-cut morals. Be clever, be kind, be good. This may be another reason why Dwarf Nose never really took off in the States. At first glance one would assume that the moral would be about not judging by appearances. Dwarf Nose’s parents cannot comprehend that their beautiful boy is now ugly, and so they throw him out. He gets a job as a chef but does not search out a remedy until the goose he rescues gives him some hope. I was fully prepared for him to remain under his spell for the rest of his life without regrets, but of course that doesn’t happen. He’s restored to his previous beauty, he returns to his parents who welcome him with open arms, and he doesn’t even marry the goose girl. Hauff ends with a brief mention of a silly war that occurred thanks to Dwarf Nose’s disappearance ending with the sentence, “Small causes, as we see, often have great consequences, and this is the story of Dwarf Nose.” That right there would be your moral then. Not an admonishment to avoid judging the outward appearance of a thing (though Dwarf Nose’s talents drill that one home pretty clearly) but instead that a little thing can lead to a great big thing.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

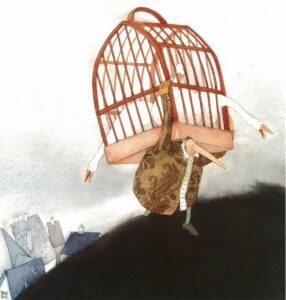

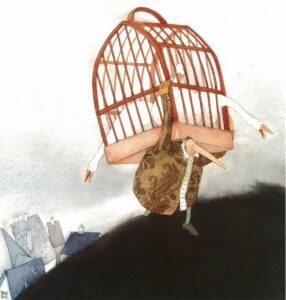

Lisbeth Zwerger is a fascinating illustrator with worldwide acclaim everywhere except, perhaps, America. It’s not that her art feels too “foreign” for U.S. palates, necessarily. I suspect that as with the concerns with the length of Dwarf Nose, Zwerger’s art is usually seen as too interstitial for this amount of text. We want more art! More Zwerger! I’ve read a fair number of her books over the years, so I was unprepared for some of the more surreal elements of this one. In one example the witch Herbwise is described as tottering in a peculiar fashion. “…it was as if she had wheels on her legs, and might tumble over any moment and fall flat on her face on the paving stones.” For this, Zwerger takes Hauff literally. Her witch is more puppet than woman, with legs like bicycle wheels and a face like a Venetian plague doctor. We have the slightly unnerving sensation that the book we are reading is, in fact, a performance put on for our enjoyment. That’s not a bad thing, but it is unexpected.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

On shelves April 1st.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Misc: Check out this fantastic review of the same book by 32 pages.

.

.

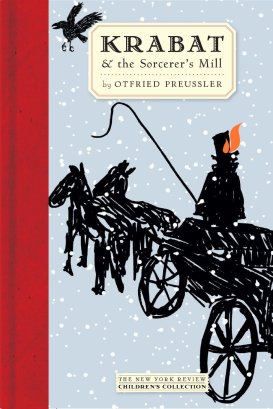

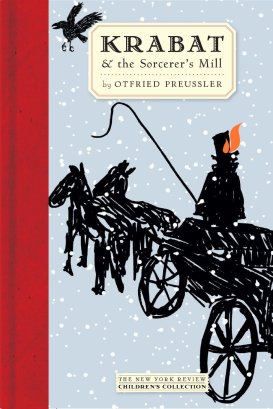

Krabat and the Sorcerer’s Mill

written by Otfried Preussler

translated from German by Anthea Bell

The New York Review Children’s Collection 9/23/2014

978-1-59017-778-5

Age 9 to 13 258 pages

.

.“New Year’s has passed. Twelfth Night is almost here. Krabat, a fourteen-year-old beggar boy dressed up as one of the Three Kings, is travelling from village to village singing carols. One night he has a strange dream in which he is summoned by a faraway voice to go to a mysterious mill—and when he wakes he is irresistibly drawn there. At the mill he finds eleven other boys, all of them, like him, the apprentices of its Master, a powerful sorcerer, as Krabat soon discovers.

During the week the boys work ceaselessly grinding grain, but on Friday nights the Master initiates them into the mysteries of the ancient Art of Arts. One day, however, the sound of church bells and of a passing girl singing an Easter hymn penetrates the boys’ prison: At last they hatch a plan that will win them their freedom and put an end to the Master’s dark designs.”

Opening

“It was between New Year’s Day and Twelfth Night, and Krabat, who was fourteen at the time, had joined forces with two other Wendish beggar boys.”

The Story

Krabat has a strange dream he feels he must follow. The next day he slips away from the other two boys in his vagabond group and goes to the mill of the sorcerer. Krabat and eleven other boys work grinding grain for long days and nights. It is hard work and Krabat has a difficult time keeping up, until Tonda, the lead journeyman and Krabat’s new best friend, lightly touches Krabat while uttering a few words under his breath. Suddenly, Krabat can work as if he gained the strength of many men; the work is still laborious, yet Krabat can work with ease. Krabat has been with the mill almost one year when Tonda dies. Days later, Krabat, now three years older, becomes a full journeyman and a new boy replaces Tonda, sleeping in his bed and wearing his old clothes, just as Krabat had done one year earlier, though he did not know this until the new apprentice arrived that he slept in the bed and wore the clothes of the journeyman he replaced.

Year 2 is not much easier for Krabat. He thinks of Tonda regularly, who, in a dream, tells Krabat to trust Michal. Michal is similar to Tonda and helps Krabat when he needs help. The millwork is still long and hard, but he can easily get through it with the magic the Master teaches his little ravens in his Black School. Once a year, the boys mark each other with the sign of the Secret Brotherhood, pass under the yoke at the door, and take a blow to the check delivered by the Master, reaffirming their roles for another year.

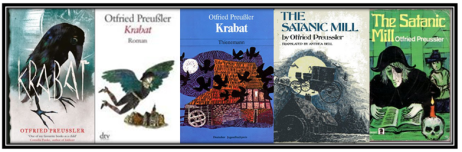

Various Covers, pt. 1

Year 3 sees Krabat ready to leave the mill. He tries to leave three times and three times, he finds himself back in the mill. He runs to the east as far as he can run—but is still on the grounds of the mill. Krabat runs to the north—only to be at the mill. Krabat can escape but one way—death. Year three’s new apprentice is one of the friends Krabat left when called to the mill. The young boy recognizes the name Krabat, tells of having a friend by that name, but does not recognize Krabat who is now many years older than the boy is. Krabat takes his friend under his wing; much like Tonda had done for him.

Krabat cannot let go of the voice of a young singer from the village. Girls and journeymen of the Master’s mill tend to end in tragedy for at least the girl—including Tonda’s girl—and often the boy as well. Krabat knows this, yet still wants to meet this girl. She could become his savior, except no one has ever outwitted the Master. With the help of a couple of other journeymen, Krabat sets about a plan to gain not only his freedom, but also that of the other journeymen as well. This would mean the end of the mill, the end of magic, and the end of the Master. The Master has his own plan involving Krabat; an offer Krabat should find hard to resist yet does. Instead, Krabat places his life in the hands of the village girl. Can this girl pull off what no one before her could?

Various Covers, pt. 2

Review

I have never been disappointed by a New York Review Children’s Book and Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill is no exception. When originally written in 1971, winning many children’s book prizes, some of the German words were archaic and difficult, especially for American children. The translator replaced those words, never losing the story or its basic scheme of horror, love, and friendship between those held in bondage. It is easy to understand why Neil Gaiman calls Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill “one of his favorite books.”

After his dream, when Krabat is walking to the mill, each person he asks for directions or simply meets, tells him to stay far away from the mill. The villagers tell him dark, strange things occur at the mill; yet Krabat ventures on, compelled to find this it. For a beggar boy the mill must seem like Heaven. Krabat gets a warm bed and filling meals that do not scrimp on meat. No more singing for his supper and traveling on foot from village to village is indeed a blessing. But the work grinding grain from dusk to dawn is laborious and leaves Krabat exhausted. Then an older boy, Tonda, steps up to help Krabat. Krabat must keep Tonda’s help secret, as the Master would not be pleased his new apprentice received assistance.

Movie Posters

The Master is unsympathetic, mysterious, and dangerous. He has secrets of his own. With only one eye, the Master seems to be able to see everything, regardless of where it might occur. Many times, he follows Krabat into town, showing up as a one-eyed raven, or a one-eyed horse, and even a one-eyed woman, all with a black patch over the useless eye—that he cannot disguise. Krabat sees these creatures but never makes the complete connection as to it being the Master.

Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill will delight kids who like adventures, mysteries, and magic. Though the Master deals in the black arts, there is nothing in the story that will scare anyone. At times, the writing feels long, and at times, it is long, yet never arduous or out of place. Preussler spins a tale so complete one wonders if such goings on really occurred in seventeenth-century Germany. Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill will keep kids entranced as they read this gothic tale of orphaned boys finding a home with a dangerous wizard. I enjoyed every word of this captivating story. Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill tends to be best for the advanced reader. Adults will also immensely enjoy this alluring tale.

KRABAT & THE SORCERER’S MILL. Text copyright © 1971 by Otfried Preussler. Copyright © 1981 by Thienemann Verlag. Translatation copyright © 1972 by Anthea Bell. Published in 2014 by the New York Review of Books.

.

Purchase Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill at Amazon —B&N—Book Depository—New York Review of Books—at your favorite bookstore.

—B&N—Book Depository—New York Review of Books—at your favorite bookstore.

Learn more about Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill HERE.

Meet the author, Otfried Preussler, at his website: http://www.preussler.de/

Meet the translator, Anthea Bell, bio wiki: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthea_Bell

Find other classic children’s books at the New York Review Children’s Collection website: http://www.nybooks.com/books/imprints/childrens/

New York Review Children’s Collection is an imprint of the New York Review of Books. http://www.nybooks.com/

Originally published in 1972, under the title The Satanic Mill.

.

Also by Otfried Preussler, (soon to be published by NYRB)

The Little Witch

The Robber Hotzenplotz

The Little Water Sprite

Also Translated by Anthea Bell

Pied Piper of Hamelin

Inkheart (Inkheart Trilogy)

The Flying Classroom (Pushkin Children’s Collection) 3/10/2015

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

copyright © 2014 by Sue Morris/Kid Lit Reviews

Filed under:

5stars,

Children's Books,

Favorites,

Library Donated Books,

Middle Grade Tagged:

Anthea Bell,

children's book reviews,

classic tale,

journeyman,

Krabat & the Sorcerer’s Mill,

magic,

middle grade book,

New York Review of Books,

Otfried Preussler,

ravens,

The New York Review Children’s Collection,

wizards

Dwarf Nose

Dwarf Nose I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus. When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one. When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

The Sendak/Orel edition was one of my favorite books as a child. Still have it. Glad to see this new interpretation by another fairy tale master.