new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2015 middle grade novels, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2015 middle grade novels in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/2/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

middle grade historical fiction,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 historical fiction,

2015 middle grade novels,

Reviews,

Best Books,

Add a tag

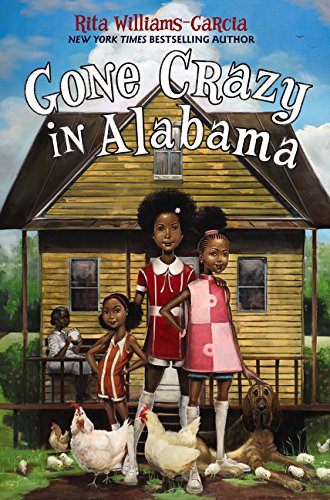

Gone Crazy in Alabama

Gone Crazy in Alabama

By Rita Williams-Garcia

Amistad (an imprint of Harper Collins)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0062215871

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

I’m a conceited enough children’s librarian that I like it when a book wins me over. I don’t want them to make it easy for me. When I sit down to read something I want to know that the author on the other side of the manuscript is scrabbling to get the reader’s attention. Granted that reader is supposed to be a 10-year-old kid and not a 37-year-old woman, but to a certain extent audience is audience. Now I’ll say right off the bat that under normal circumstances I don’t tend to read sequels and I CERTAINLY don’t review them. There are too many books published in a current year to keep circling back to the same authors over and over again. There are, however, always exceptions to the rule. And who amongst us can say that Rita Williams-Garcia is anything but exceptional? The Gaither Sisters chronicles (you could also call them the One Crazy Summer Books and I think you’d be in the clear) have fast become modern day literary classics for kids. Funny, painful, chock full of a veritable cornucopia of historical incidents, and best of all they stick in your brain like honey to biscuits. Read one of these books and you can recall them for years at a time. Now the bitter sweetness of “Gone Crazy in Alabama” gives us more of what we want (Vonetta! Uncle Darnell! Big Ma!) in a final, epic, bow.

Going to visit relatives can be a chore. Going to visit warring relatives? Now THAT is fun! Sisters Delphine, Vonetta, and Fern have been to Oakland and Brooklyn but now they’ve turned South to Alabama to visit their grandmother Big Ma, their great-grandmother Ma Charles, and Ma Charles’s half sister Miss Trotter. Delphine, as usual, places herself in charge of her younger, rebellious, sisters, not that they ever appreciate it. As she learns more about her family’s history (and the reason the two half sisters loathe one another) she ignores her own immediate family’s needs until the moment when it almost becomes too late.

I’m an oldest sister. I have two younger siblings. Unlike Delphine I didn’t have the responsibility of watching over my siblings for any extended amount of time. As a result, I didn’t pay all that much attention to them growing up. But like Delphine, I would occasionally find myself trying, to my mind anyway, to keep them in line. Where Rita Williams-Garcia excels above all her peers, and I do mean all of them, is in the exchanges between these three girls. If I had an infinite revenue stream I would solicit someone to adapt their conversations into a very short play for kids to perform somewhere (actually, I’d just like to see ALL these books as plays for children, but that’s neither here nor there). The dialogue sucks you in and you find yourself getting emotionally involved. Because Delphine is our narrator you’re getting everything from her perspective and in this the author really makes you feel like she’s on the right side of every argument. It would be an excellent writing exercise to charge a class of sixth graders with the task of rewriting one of these sections from Vonetta or Fern’s point of view instead.

As I might have mentioned before, I wasn’t actually sold initially on this book. Truth be told, I liked the sequel to One Crazy Summer (called P.S. Be Eleven) but found the ending rushed and a tad unsatisfying. That’s just me, and my hopes with Gone Crazy were not initially helped by this book’s beginning. I liked the set-up of going South and all that, but once they arrived in Alabama I was almost immediately confused. We met Ma Charles and then very soon thereafter we met another woman very much like her who lived on the other side of a creek. No explanation was forthcoming about these two, save some cryptic descriptions of wedding photos, and I felt very much out to sea. My instinct is to say that a child reader would feel the same way, but kids have a way of taking confusing material at face value, so I suspect the confusion was of the adult variety more than anything else. Clearly Ms. Williams-Garcia was setting all this up for the big reveal of the half-sister’s relationship, and I appreciated that, but at the same time I thought it could have been introduced in a different way. Things were tepid for me for a while, but then the story really started picking up. By the time we got to the storm, I was sold.

And it was at this point in the book that I realized that I’d been coming at the book all wrong. Williams-Garcia was feeding me red herrings and I’m gulping them down like there’s no tomorrow. This book isn’t laser focusing its attention on great big epic themes of historical consequence. All this book is, all it ever has been, all the entire SERIES is about in its heart of hearts, is family. And that’s it. The central tension can be boiled down to something as simple and effective as whether or not Delphine and Vonetta can be friends. Folks are always talking about bullying and bully books. They tend to involve schoolmates, not siblings, but as Gone Crazy in Alabama shows, sometimes bullying is a lot closer to home than anyone (including the bully) is willing to acknowledge.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about needing more diverse books for kids, and it’s absolutely a valid concern. I have always been of the opinion, however, that we also need a lot more funny diverse books. When most reading lists’ sole hat tip to the African-American experience is Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (no offense to Mildred D. Taylor, but you see what I’m getting at here) while the white kids star in books like Harriet the Spy and Frindle, something’s gotta change. We Need Diverse Books? We Need FUNNY Diverse Books too. Something someone’s going to enjoy reading and want to pick up again. That’s why Christopher Paul Curtis has been such a genius the last few years (because, seriously, who else would explore the ramifications of vomiting on Frederick Douglass?) and why the name Rita Williams-Garcia will be remembered long after you and I are tasty toasty worm food. Because this book IS funny while also balancing out pain and hurt and hope.

An interviewer once asked Ms. Williams-Garcia if she ever had younger sisters like the ones in this book or if she’d ever spent a lot of time in rural Alabama, like they do here. She replied good-naturedly that nope. It reminded me of that story they tell about Dustin Hoffman playing Richard III. He put stones in his shoes to get the limp right. Laurence Olivier caught wind of this and his response was along the lines of, “My dear boy, why don’t you try acting?” That’s Ms. Williams-Garcia for you. She does honest-to-goodness writing. Writing that can conjure up estranged siblings and acts of nature. Writing that will make you laugh and think and think again after that. Beautifully done, every last page. A trilogy winds down on just the right note.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 8/25/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

middle grade,

Simon and Schuster,

Best Books,

Kenneth Oppel,

Jon Klassen,

scary books for kids,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 middle grade novels,

Add a tag

The Nest

The Nest

By Kenneth Oppel

Illustrated by Jon Klassen

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-4814-3232-0

On shelves October 6th

Oh, how I love middle grade horror. It’s a very specific breed of book, you know. Most people on the street might think of the Goosebumps books or similar ilk when they think of horror stories for the 10-year-old set, but that’s just a small portion of what turns out to be a much greater, grander set of stories. Children’s book horror takes on so many different forms. You have your post-apocalyptic, claustrophobic horrors, like Z for Zachariah by Robert C. O’Brien. You have your everyday-playthings-turned-evil tales like Doll Bones by Holly Black. You have your close family members turned evil stories ala Coraline by Neil Gaiman and Wait Till Helen Comes by Mary Downing Hahn. And then there are the horror stories that shoot for the moon. The ones that aren’t afraid (no pun intended) to push the envelope a little. To lure you into a false sense of security before they unleash some true psychological scares. And the best ones are the ones that tie that horror into something larger than themselves. In Kenneth Oppel’s The Nest, the author approaches us with a very simple idea. What if your desire to make everything better, everyone happier, released an unimaginable horror? What do you do?

New babies are often cause for true celebration, but once in a while there are problems. Problems that render parents exhausted and helpless. Problems with the baby that go deep below the surface and touch every part of your life. For Steve, it feels like it’s been a long time since his family was happy. So when the angels appear in his dream offering to help with the baby, he welcomes them. True, they don’t say much specifically about what they can do. Not at the beginning, but why look a gift horse in the mouth? Anyway, there are other problems in Steve’s life as well. He may have to go back into therapy, and then there are these wasps building a nest on his house when he’s severely allergic to them. A fixed baby could be the answer to his prayers. Only, the creatures visiting him don’t appear to be angels anymore. And when it comes to “fixing” the baby . . . well, they may have other ideas entirely . . .

First and foremost, I don’t think I can actually talk about this book without dusting off the old “spoiler alert” sign. For me, the very fact that Oppel’s book is so beautifully succinct and restrained, renders it impossible not to talk about its various (and variegated) twists and turns. So I’m going to give pretty much everything away in this review. It’s a no holds barred approach, when you get right down to it. Starting with the angels of course. They’re wasps. And it only gets better from there.

It comes to this. I’ve no evidence to support this theory of mine as to one of the inspirations for the book. I’ve read no interviews with Oppel about where he gets his ideas. No articles on his thought processes. But part of the reason I like the man so much probably has to do with the fact that at some point in his life he must have been walking down the street, or the path, or the trail, and saw a wasp’s nest. And this man must have looked up at it, in all its paper-thin malice, and found himself with the following inescapable thought: “I bet you could fit a baby in there.” And I say unto you, it takes a mind like that to write a book like this.

Wasps are perhaps nature’s most impressive bullies. They seem to have been given such horrid advantages. Not only do they have terrible tempers and nasty dispositions, not only do they swarm, but unlike the comparatively sweet honeybee they can sting you multiple times and never die. It’s little wonder that they’re magnificent baddies in The Nest. The only question I have is why no one has until now realized how fabulous a foe they can be. Klassen’s queen is particularly perfect. It would have been all too easy for him to imbue her with a kind of White Witch austerity. Queens come built-in with sneers, after all. This queen, however, derives her power by being the ultimate confident. She’s sympathetic. She’s patient. She’s a mother who hears your concerns and allays them. Trouble is, you can’t trust her an inch and underneath that friendliness is a cold cruel agenda. She is, in short, my favorite baddie of the year. I didn’t like wasps to begin with. Now I abhor them with a deep inner dread usually reserved for childhood fears.

I mentioned earlier that the horror in this book comes from the idea that Steve’s attempts to make everything better, and his parents happier, instead cause him to consider committing an atrocity. In a moment of stress Steve gives his approval to the unthinkable and when he tries to rescind it he’s told that the matter is out of his hands. Kids screw up all the time and if they’re unlucky they screw up in such a way that their actions have consequences too big for their small lives. The guilt and horror they sometimes swallow can mark them for life. The queen of this story offers something we all can understand. A chance to “fix” everything and make the world perfect. Never mind that perfect doesn’t really exist. Never mind that the price she exacts is too high. If she came calling on you, offering to fix that one truly terrible thing in your life, wouldn’t you say yes? On the surface, child readers will probably react most strongly to the more obvious horror elements to this story. The toy telephone with the scratchy voice that sounds like “a piece of metal being held against a grindstone.” The perfect baby ready to be “born” The attic . . . *shudder* Oh, the attic. But it’s the deeper themes that will make their mark on them. And on anyone reading to them as well.

There are books where the child protagonist’s physical or mental challenges are named and identified and there are books where it’s left up to the reader to determine the degree to which the child is or is not on such a spectrum. A book like Wonder by R.J. Palacio or Out of My Mind by Sharon Draper will name the disability. A book like Emma-Jean Lazarus Fell Out of a Tree by Lauren Tarshis or Counting by 7s by Holly Sloan won’t. There’s no right or wrong way to write such books, and in The Nest Klassen finds himself far more in the latter rather than former camp. Steve has had therapy in the past, and exhibits what could be construed to be obsessive compulsive behavior. What’s remarkable is that Klassen then weaves Steve’s actions into the book’s greater narrative. It becomes our hero’s driving force, this fight against impotence. All kids strive to have more control over their own lives, after all. Steve’s O.C.D. (though it is never defined in that way) is part of his helpless attempt to make things better, even if it’s just through the recitation of lists and names. At one point he repeats the word “congenital” and feels better, “As if knowing the names of things meant I had some power over them.”

When I was a young adult (not a teen) I was quite enamored of A.S. Byatt’s book Angels and Insects. It still remains one of my favorites and though I seem to have transferred my love of Byatt’s prose to the works of Laura Amy Schlitz (her juvenile contemporary and, I would argue, equivalent) there are elements of Byatt’s book in what Klassen has done here. His inclusion of religion isn’t a real touchstone of the novel, but it’s just a bit too prevalent to ignore. There is, for example, the opening line: “The first time I saw them, I thought they were angels.” Followed not too long after by a section where Steve reads off every night the list of people he wants to keep safe. “I didn’t really know who I was asking. Maybe it was God, but I didn’t really believe in God, so this wasn’t praying exactly.” He doesn’t question the angels of his dreams or their desire to help (at least initially). And God makes no personal appearance in the novel, directly or otherwise. Really, when all was said and done, my overall impression was that the book reminded me of David Almond’s Skellig with its angel/not angel, sick baby, and boy looking for answers where there are few to find. The difference being, of course, the fact that in Skellig the baby gets better and here the baby is saved but it is clear as crystal to even the most optimistic reader that it will never ever been the perfect baby every parent wishes for.

It’s funny that I can say so much without mentioning the language, but there you go. Oppel’s been wowing folks with his prose for years, but that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy a cunning turn of phrase when you encounter it. Consider some of his lines. The knife guy is described like “He looked like his bones were meant for an even bigger body.” A description of a liquid trap for wasps is said to be akin to a, “soggy mass grave, the few survivors clambering over the dead bodies, trying in vain to climb out. It was like a vision of hell from that old painting I’d seen in the art gallery and never forgotten.” Or what may well be my favorite in the book, “… and they were regurgitating matter from their mouths and sculpting it into baby flesh.” And then there are the little elements the drive the story. We don’t learn the baby’s name until page 112. Or the very title itself. When Vanessa, Steve’s babysitter, is discussing nests she points out that humans make them as well. “Our houses are just big nests, really. A place where you can sleep and be safe – and grow.”

The choice of Jon Klassen as illustrator is fascinating to me. When I think of horror illustrations for kids the usual suspects are your Stephen Gammells or Gris Grimleys or Dave McKeans. Klassen’s different. When you hire him, you’re not asking him to ratchet up the fear factor, but rather to echo it and then take it down a notch to a place where a child reader can be safe. Take, for example, his work on Lemony Snicket’s The Dark A book where the very shadows speak, it wasn’t that Klassen was denying the creepier elements of the tale. But he tamed them somehow. And now that same taming sense is at work here. His pictures are rife with shadows and faceless adults, turned away or hidden from the viewer (and the viewer is clearly Steve/you). And his pictures do convey the tone of the book well. A curved knife on a porch is still a curved knife on a porch. Spend a little time flipping between the front and back endpapers, while you’re at it. Klassen so subtle with these. The moon moves. A single light is out in a house. But there’s a feeling of peace to the last picture, and a feeling of foreboding in the first. They’re practically identical so I don’t know how he managed that, but there it is. Honestly, you couldn’t have picked a better illustrator.

Suffice to say, this book would probably be the greatest class readaloud for fourth, fifth, or sixth graders the world has ever seen. When I was in fourth grade my teacher read us The Wicked Wicked Pigeon Ladies in the Garden by Mary Chase and I was never quite the same again. Thus do I bless some poor beleaguered child with the magnificent nightmares that will come with this book. Added Bonus for Teachers: You’ll never have to worry about school attendance ever again. There’s not a chapter here a kid would want to miss.

If I have a bone to pick with the author it is this: He’s Canadian. Normally, this is a good thing. Canadians are awesome. They give us a big old chunk of great literature every year. But Oppel as a Canadian is terribly awkward because if he were not and lived in, say, Savannah or something, then he could win some major American children’s literary awards with this book. And now he can’t. There are remarkably few awards the U.S. can grant this tale of flying creepy crawlies. Certainly he should (if there is any justice in the universe) be a shoo-in for Canada’s Governor General’s Award in the youth category and I’m pulling for him in the E.B. White Readaloud Award category as well, but otherwise I’m out to sea. Would that he had a home in Pasadena. Alas.

Children’s books come with lessons pre-installed for their young readers. Since we’re dealing with people who are coming up in the world and need some guidance, the messages tend towards the innocuous. Be yourself. Don’t judge a book by its cover. Friendship is important. Etc. The message behind The Nest could be debated ad nauseam for quite some time, but I think the thing to truly remember here is something Steve says near the end. “And there’s no such thing as normal anyways.” The belief in normality and perfection may be the truest villain in The Nest when you come right down to it. And Klassen has Steve try to figure out why it’s good to try to be normal if there is no true normal in the end. It’s a lesson adults have yet to master ourselves. Little wonder that The Nest ends up being what may be the most fascinating horror story written for kids you’ve yet to encounter. Smart as a whip with an edge to the terror you’re bound to appreciate, this is a truly great, truly scary, truly wonderful novel.

On shelves October 6th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus,

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/31/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

fantasy,

middle grade,

middle grade fantasy,

Best Books,

Kelly Jones,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 fantasy,

2015 middle grade novels,

funny fantasy,

Katie Kath,

Add a tag

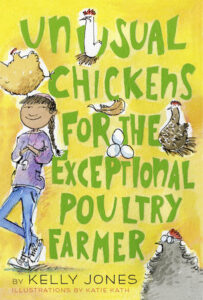

Unusual Chickens for the Exceptional Poultry Farmer

Unusual Chickens for the Exceptional Poultry Farmer

By Kelly Jones

Illustrated by Katie Kath

Alfred A. Knopf (an imprint of Random House Children’s Books)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-385-75552-8

On shelves now

The epistolary novel has a long and storied history. At least when it comes to books written for adults. So too does it exist in novels for children, but in my experience you are far more likely to find epistolary picture books than anything over 32 pages in length. That doesn’t stop teachers, of course. As a children’s librarian I often see the kiddos come in with the assignment to read an epistolary novel and lord love a duck if you can remember one on the spot. I love hard reference questions but if you were to ask me to name five such books in one go I’d be scrambling for my internet double quick time. Of course now that I’ve read Unusual Chickens for the Exceptional Poultry Farmer I will at long last be able to pull at least one book from my crazy overstuffed attic of a brain instantaneously. Kelly Jones’s book manages with charm and unexpected panache to take the art of chicken farming and turn it into a really compelling narrative. Beware, though. I suspect more than one child will leave this book desirous of a bit of live poultry of their very own. You have been warned.

After her dad lost his job, it really just made a lot of sense for Sophie and her family to move out of L.A. to her deceased great-uncle Jim’s farm. Still, it’s tough on her. Not only are none of her old friends writing her back but she’s having a hard time figuring out what she should do with herself. She spends some of her time writing her dead Abuelita, some of her time writing Jim himself (she doesn’t expect answers), and some of her time writing Agnes of the Redwood Farm Supply. You see, Sophie found a chicken in her back yard one day and there’s something kind of strange about it. Turns out, Uncle Jim used to collect chickens that exhibited different kinds of . . . abilities. Now a local poultry farmer wants Jim’s chickens for her very own and it’s up to Sophie to prove that she’s up to the task of raising chickens of unusual talents.

There are two different types of children’s fantasy novels, as I see it. The first kind spends inordinate amounts of time world building. They will never let a single thread drop or question remain unanswered. Then there’s the second kind. These are the children’s novels where you may have some questions left at the story’s end, but you really don’t care. That’s Unusual Chickens for me. I simply couldn’t care two bits about the origins of these unusual chickens or why there was an entire company out there providing them in some capacity. What Ms. Jones does so well is wrap you up in the emotions of the characters and the story itself, so that details of this sort feel kind of superfluous by the end. Granted, that doesn’t mean there isn’t going to be the occasional kid demanding answers to these questions. You can’t help that.

There are two different types of children’s fantasy novels, as I see it. The first kind spends inordinate amounts of time world building. They will never let a single thread drop or question remain unanswered. Then there’s the second kind. These are the children’s novels where you may have some questions left at the story’s end, but you really don’t care. That’s Unusual Chickens for me. I simply couldn’t care two bits about the origins of these unusual chickens or why there was an entire company out there providing them in some capacity. What Ms. Jones does so well is wrap you up in the emotions of the characters and the story itself, so that details of this sort feel kind of superfluous by the end. Granted, that doesn’t mean there isn’t going to be the occasional kid demanding answers to these questions. You can’t help that.

I have a bit of a thing against books that present you with unnecessary twists at their ends. If some Deus Ex Machina ending solves everything with a cute little bow then I am well and truly peeved. And there is a bit of a twist near the end of Unusual Chickens but it’s more of a funny one than something that makes everything turn out all right. The style of writing the entire book in letters of one sort or another works very well when it comes to revealing one of the book’s central mysteries. Throughout the story Sophie engages the help of Agnes of the Redwood Farm Supply (the company that provided her uncle with the chickens in the first place). When she at last discovers why Agnes’s letters have been so intermittent and peculiar the revelation isn’t too distracting, though I doubt many will see it coming.

Now the book concludes with Sophie overcoming her fear of public speaking in order to do the right thing and save her chickens. She puts it this way: “One thing my parents agree on is this: if people are doing something unfair, it’s part of our job to remind them what’s fair, even if sometimes it still doesn’t turn out the way we want it to.” That’s a fair lesson for any story and a good one to drill home. I did find myself wishing a little that Sophie’s fears had been addressed a little more at the beginning of the book rather that simply solved without too much build up at the end, but that’s a minor point. I like the idea of telling kids that doing the right thing doesn’t always give you the outcome you want, but at least you have to try. Seems to have all sorts of applications in real life.

In an age where publishers are being held increasingly accountable for diverse children’s fare, it’s still fair to say that Unusual Chickens is a rare title. I say this because it’s a book where the main character isn’t white, that’s not the point of the story, but it’s also not a fact that’s completely ignored either. Sophie has dark skin and a Latino mom. Since they’ve moved to the country (Gravenstein, CA if you want to be precise) she feels a bit of an outsider. “I miss L.A. There aren’t any people around here- especially no brown people except Gregory, our mailman.” She makes casual reference to the ICE and her mother’s understanding that “you have to be twice as honest and neighborly when everyone assumes you’re an undocumented immigrant…” And there’s the moment when Sophie mentions that the librarian still feels about assuming that Sophie was a child of the help, rather than the grandniece of the Blackbird Farm’s previous owner. A lot of books containing a character like Sophie would just mention her race casually and then fear mentioning it in any real context. I like that as an author, Jones doesn’t dwell on her character’s ethnicity, but neither does she pretend that it doesn’t exist.

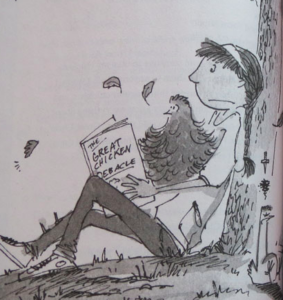

You know that game you sometimes play with yourself where you think, “If I absolutely had to have a tattoo, I think I’d have one that looked like [blank]”? Well, for years I’ve only had one figure in mind. A little dancing Suzuki Beane, maybe only as large as a dime, on the inner wrist of my right hand. I’ll never get this tattoo but it makes me happy to think that it’s always an option. I am now going to add a second fictional tattoo to my roster. Accompanying Suzuki on my left wrist would be Henrietta. She’s the perpetually peeved, occasionally telekinetic, and she makes me laugh every single time I see her. Henrietta’s creator, in a sense, is the illustrator of this book, Ms. Katie Kath. I was unfamiliar with her work, prior to reading Unusual Chickens and from everything I can tell this is her children’s book debut. You’d never know it from her style, of course. Kath’s drawing style here has all the loose ease and skill of a Quentin Blake or a Jules Feiffer. When she draws Sophie or her family you instantly relate to them, and when she draws chickens she makes it pretty clear that no other illustrator could have brought these strange little chickies to life in quite the same way. These pages just burst with personality and we have her to thank.

You know that game you sometimes play with yourself where you think, “If I absolutely had to have a tattoo, I think I’d have one that looked like [blank]”? Well, for years I’ve only had one figure in mind. A little dancing Suzuki Beane, maybe only as large as a dime, on the inner wrist of my right hand. I’ll never get this tattoo but it makes me happy to think that it’s always an option. I am now going to add a second fictional tattoo to my roster. Accompanying Suzuki on my left wrist would be Henrietta. She’s the perpetually peeved, occasionally telekinetic, and she makes me laugh every single time I see her. Henrietta’s creator, in a sense, is the illustrator of this book, Ms. Katie Kath. I was unfamiliar with her work, prior to reading Unusual Chickens and from everything I can tell this is her children’s book debut. You’d never know it from her style, of course. Kath’s drawing style here has all the loose ease and skill of a Quentin Blake or a Jules Feiffer. When she draws Sophie or her family you instantly relate to them, and when she draws chickens she makes it pretty clear that no other illustrator could have brought these strange little chickies to life in quite the same way. These pages just burst with personality and we have her to thank.

Now there are some fairly long sections in this book that discuss the rudimentary day-to-day realities of raising chickens. Everything from the amount of food (yes, the book contains math problems worked seamlessly into the narrative) to different kinds of housing to why gizzards need small stones inside of them. These sections are sort of like the whaling sections in Moby Dick or the bridge sections in The Cardturner. You can skip right over them and lose nothing. Still, I found them oddly compelling. People love process, particularly when that process is so foreign to their experience. I actually heard someone who had always lived in the city say to me the other day that before they read this book they didn’t know that you needed a rooster to get baby chickens. You see? Learning!

I don’t say that this book is going to turn each and every last one of its readers into chicken enthusiasts. I also know that it paints a rather glowing portrait of chicken ownership that is in direct contrast to the farm situation perpetuated on farmers today. But doggone it, it’s charming to its core. We see plenty of magical animal books churned out every year. Magical zoos and magical veterinarians and magical bestiaries. So what’s wrong with extraordinary chickens as well? Best of all, you don’t have to be a fantasy fan to enjoy this book. Heck, you don’t have to like chickens. The writing is top notch, the pictures consistently funny, and the story rather moving. Everything, in fact, a good chapter book for kids should be. Hand it to someone looking for lighthearted fare but that still wants a story with a bit of bite to it. Great stuff.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Reviews: educating alice

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 2/25/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 historical fiction,

2015 middle grade novels,

Alison DeCamp,

Crown Books for Young Readers,

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Random House,

Best Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

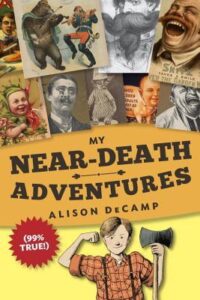

My Near-Death Adventures (99% True)

My Near-Death Adventures (99% True)

By Alison DeCamp

Crown Books for Young Readers (an imprint of Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-385-39044-6

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Children’s historical fiction novels often divide up one of two ways. In the first category you have your important moments in history. In such books our heroes run about and encounter these moments by surprise. Extra points if it happens to be a Great Big Bad Moment in history as well. Then in the second category are the books that have opted to go a more difficult route. They may be well grounded in a time period of the past, but they do not require historical cameos or Great Big Bad Moments to transport their readers. Such books run a very great risk of, quite frankly, becoming dull. Read enough of them and, with the exception of a few, they all run together. Humor often helps me distinguish them from the pack. After all, would Catherine Called Birdy command quite so many hearts and minds if it weren’t also deeply amusing? Still, it’s rare to find fiction set in the past for kids that’s quite that original. It takes a certain kind of devious brain to hit on an all-new take. Enter My Near-Death Adventures by Alison DeCamp. Falling squarely into the second category rather than the first, this 1895 charmer utilizes plenty of visuals along with an unreliable narrator and classic comedic setting. I can say with certainty that your kids will never read a work of lumberjack fiction quite as fast and funny as this ever again.

Well, sir, it looks like Stan’s found himself in a heap of trouble. First off there’s the difficulty with his dead father. The problem? He’s not dead. He’s nowhere around, and now he seems to have divorced Stan’s mama, but dead he is not. Then there’s the fact that it’s the middle of winter yet Stan’s mama and his 95% evil Granny (her percentage fluctuates a lot) are packing him up and they’re all heading up to some godforsaken lumber camp in the middle of nowhere. Of course, that’s good for Stan since he’s been hoping to build up his manly skills so that he can support his mama. Unfortunately his cousin Geri, who seems to revel in torturing him, will be there as well. Can Stan fight off his mother’s multiple suitors, keep his eye on the lumberjack he’s dubbed “Stinky Pete”, and learn to be a man (if Geri doesn’t kill him first) all at once? If anyone can, it’s Stan. Probably.

Humor in historical fiction can come across as a case where the contemporary author is shoehorning his or her own beliefs onto characters from the past. Often when this happens it feels fake. I remember once reading a children’s novel set in the Civil War South where an enterprising young woman, with no outside influences, actually said, “Corsets don’t just restrict the waist. They restrict the mind,” or something equally out of left field. So to what extent are anachronisms a threat in books of this sort? For example, would someone like Stan really have called his cousin “Scary Geri”? For me, I don’t worry as much about the small details. If the language isn’t strictly of the late 19th century variety then who in the Sam Hill cares? (Forgive my language, granny.) It’s the big things (like mind restricting corsets) that catch my eye. With that in mind, I was somewhat relieved when I realized that Stan is a sexist jerk. He quite believably does not look on women’s accomplishments as something to commend (which, in turn, is an interesting way of building up sympathy for his cousin Geri). In other words, he’s of his time.

To bring the funny, DeCamp does two things I’ve not seen done in works of historical fiction before. The first involves a ton of late 19th/early 20th century advertisements. Using the conceit that this is Stan’s scrapbook, each image makes some kind of commentary on what Stan is describing. They’re also hilarious. I cannot help but imagine the countless hours DeCamp spent poring through advertisement after advertisement. One wonders if there were parts of the narrative wholly reliant on the existence of one ad or another. Hard to say.

The second clever and hitherto unknown thing DeCamp does with her storytelling is to make Stan an unreliable narrator with unreliable narration. Which is to say, you’ll be reading his private thoughts on the page when suddenly another character will comment on what clearly should have been kept inside Stan’s brain. The end result is that the reader will lapse into a continual sense of security, safe in the knowledge that what they’re reading isn’t dialogue (after all, there aren’t any quotation marks) and then, exactly like Stan, the reader will be shocked when someone comments on information they shouldn’t know anything about. It really puts you directly into Stan’s shoes and helps to make him more relatable. Which is good since he runs the risk of being considered unsympathetic as a character.

Unreliable as a narrator, potentially unsympathetic as a human being, Stan still wins our love. Why? He’s Kid Falstaff! A coward you root for and love, yet still don’t always approve of. Still, even in the depths of his own delusion, how can you not love the guy? He’s a Yooper Telemachus fending unworthy suitors off of his mama. And even when you’ve taken almost all you can take from the guy, you’ll find him saying something like, “This is the furthest I’ve ever felt from being a man. All I really want to do is cuddle up in bed and have Mama read me a book. Or play with the toy soldiers still lined up on my windowsill in the apartment house. But I can’t. Because that’s not manly, and being manly is the only way I’ll ever understand my father . . .” Poor kid.

A good author, by the way, allows their supporting characters some personal growth as well. It doesn’t all have to come from the protagonist, after all. In this particular case it’s Stan’s mama, a character that could easily have just been some passive, maternal bit of nothingness, who comes into her own. For years she’s been held down pretty effectively by her own mother. Now she has a chance at making a bit of a life for herself, choosing her own mate (or not choosing, as the case may be), and generally having a bit of fun. I know no kid reading this book is going to care, but I appreciated having someone other than Stan learn and grow.

I sit here secure in the knowledge that somewhere, at some time, an enterprising adult (be it teacher, parent, or librarian) will take it upon themselves to actually follow Mrs. Cavanaugh’s recipe for Vinegar Pie. The recipe is right there in black and white in the book, clear as crystal. If you have any goodness in your heart and you are tempted to tread this path, here is a bit of advice: don’t. It’s called Vinegar Pie, for crying out loud! What part of that sounds appetizing? You know what is appetizing? This book. Hilarious and heartbreaking and funny funny funny. You know what you hand a kid that gets the dreaded, “Read one work of historical fiction” assignment in school? You hand them this and then sit back to wait for their inevitable gratitude. They may never say thank you to your face, but you’ll be able to rest safe and secure in the knowledge that they loved this book. Or, at the very least, found it enticing and intriguing. 99-100% fantastic.

On shelves now.

Source:

Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

Videos:

Oo! Peppy little trailer here, no?

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 2/5/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Best Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

Kimberly Brubaker Bradley,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 historical fiction,

2015 middle grade novels,

2016 Newbery contender,

Add a tag

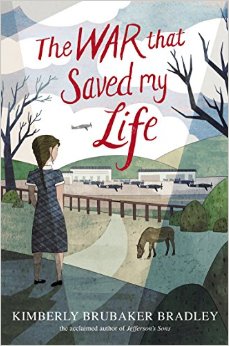

The War That Saved My Life

The War That Saved My Life

By Kimberly Brubaker Bradley

Dial Books for Young Readers (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISBN: 9780803740815

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

As a child I was what one might call a selective reader. Selective in that I studiously avoided any and all works of fiction that might conceivably be considered “depressing”. Bridge to Terabithia? I’ll have none please. Island of the Blue Dolphins? Pass. Jacob Have I Loved? Not in this lifetime. Lord only knows what caused a book to be labeled “depressing” in my eyes before I’d even read it. I think I went by covers alone. Books picturing kids staring out into the vast nothingness of the universe were of little use to me. Happily I got over this phase and eventually was able to go back to those books I had avoided to better see what I had missed. Still, that 10-year-old self is always with me and I confer with her when I’m reading new releases. So when I read The War That Saved My Life I had to explain to her, at length, that in spite of the premise, cover (again with the kids staring out into nothingness), and time period this isn’t the bleak stretch of depressingness it might appear to be. Enormously satisfying and fun to read, Bradley takes a work of historical fiction and gives the whole premise of WWII evacuees a kick in the pants.

Ada is ten and as far as she can tell she’s never been outdoors. Never felt the sun on her face. Never seen grass. Born with a twisted foot her mother considers her an abomination and her own personal shame. So when the chance comes for Ada to join her fellow child evacuees, including her little brother Jamie, out of the city during WWII she leaps at the chance. Escaping to the English countryside, the two are foisted upon a woman named Susan who declares herself to be “not nice” from the start. Under her care the siblings grow and change. Ada discovers Susan’s pony and is determined from the get-go to ride it. And as the war progresses and things grow dire, she finds that the most dangerous thing isn’t the bombs or the war itself. It’s hope. And it’s got her number.

I may have mentioned it before, but the word that kept coming to mind as I read this book was “satisfying”. There’s something enormously rewarding about this title. I think a lot of the credit rests on the very premise. When a deserving kid receives deserving gifts, it releases all kinds of pleasant endorphins in the brain of he reader. It feels like justice, multiple times over. We’re sympathetic to Ava from the start, but I don’t know that I started to really like her until she had to grapple with the enormity of Susan’s sharp-edged kindness. As an author, Bradley has the unenviable job of making a character like Ada realistic, suffering real post-traumatic stress in the midst of a war, and then in time realistically stronger. This isn’t merely a story where the main character has to learn and grow and change. She has this enormous task of making Ava strong in every possible way after a lifetime of systematic, often horrific, abuse. And she has to do so realistically. No deus ex machina. No sudden conversion out of the blue. That she pulls it off is astounding. Honestly it made me want to reread the book several times over, if only to figure out how she managed to display Ada’s anger and shock in the face of kindness with such aplomb. For me, it was the little lines that conveyed it best. Sentences like the one Ada says after the first birthday she has ever celebrated: “I had so much. I felt so sad.” It’s not a flashy thing to say. Just true.

You can see the appeal of writing characters like Ada and Jamie. Kids who have so little experience with the wider world that they don’t know a church from a bank or vice versa. The danger with having a character ignorant in this way is that they’ll only serve to annoy the reader. Or, perhaps worse, their inability to comprehend simple everyday objects and ideas will strike readers as funny or something to be mocked. Here, Bradley has some advantages over other books that might utilize this technique. For one thing, by placing this book in the past Ada is able to explain to child readers historical facts without stating facts that would be obvious to her or resorting to long bouts of exposition. By the same token, child readers can also pity Ada for not understanding stuff that they already do (banks, church, etc.).

Ms. Bradley has written on her blog that, “I don’t write in dialect, for several reasons, but I try to write dialogue in a way that suggests dialect.” American born (Indiana, to be specific) she has set her novel in historical England (Kent) where any number of accents might be on display. She could have peppered the book with words that tried to replicate the sounds of Ada’s London accent or Susan’s Oxford educated one. Instead, Ms. Bradley is cleverer than that. As she says, she merely suggests dialect. One of the characters, a Mr. Grimes, says things like “Aye” and ends his sentences with words like “like”. But it doesn’t feel forced or fake. Just mere hints of an accent that would allow a reader to pick it up or ignore it, however they preferred.

Basically what we have here is Anne of Green Gables without quite so much whimsy. And in spite of the presence of a pony, this is not a cutesy pie book. Instead, it’s a story about a girl who fights like a demon against hope. She fights it with tooth and claw and nail and just about any weapon she can find. If her life has taught her anything it’s that hope can destroy you faster than abuse. In this light Susan’s kindness is a danger unlike anything she’s ever encountered before. Ms. Bradley does a stellar job of bringing to life this struggle in Ada and in inflaming a similar struggle in the hearts of her young readers. You root for Ada. You want her to be happy. Yet, at the same time, you don’t want your heart to be broken any more than Ada does. Do you hope for her future then? You do. Because this is a children’s book and hope, in whatever form it ultimately takes, is the name of the game. Ms. Bradley understands that and in The War That Saved My Life she manages to concoct a real delight out of a story that in less capable hands would have been a painful read. This book I would hand to my depression-averse younger self. It’s fun. It’s exciting. It’s one-of-a-kind.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Notes on the Cover: I may poke fun at the fact that this cover looks so much like the “serious” ones I avoided like the plague in my youth, but I should point out that it’s doing something that almost no other similar children’s books dare. Inevitably if a book is about a kid with a physical ailment of some sort, that ailment will not make the cover. Much as publishers avoid putting overweight kids on book jackets, so too do they avoid physical disabilities. Here, however, the artist has shown Ada’s foot, albeit in a simplified manner. It’s not particularly noticeable but it’s there. I’ll take what I can get.

Professional Reviews:

Misc: The author stops by Matthew Winner’s fabulous Let’s Get Busy podcast to chat.

Video: And finally, see Ms. Brubaker Bradley talk about the book herself.

Gone Crazy in Alabama

Gone Crazy in Alabama

I think this is the best book of 2015.

It’s interesting. I think the reason it took me so long to get to reviewing it was that I had to talk to lots of people about it and process it myself. In the end, I really do think it has a Newbery chance. It wouldn’t be the first book in a series to win the Award where its predecessor did not (though One Crazy Summer tends to be my It Shoulda Won example time and time again). But I needed something like seven months to reach this conclusion.

I appreciate the work and time you put into your blog each day. Reading your thoughts and comments help deepen my appreciation and understanding of each book you review. The interactions among Delphine, Vonetta, Fern, and all their relatives greatly interested and often amused me. These three books are favorites of mine. I look forward to visiting these three sisters again during rereads and also look forward to future work from Ms. Williams-Garcia.

Thank you again, Betsy, for all you do.

About family and, even moreso, about sisters. The character development of those three girls is simply brilliant. Through talk, through body language (I think of Fern’s punching down of her fists when upset), through circumstances (Fern and the chickens), the cool little things like Charlotte’s Web versus Things Fall Apart. I adore this book and am overdue writing my own blog post — which will be arguing for why it should be a serious Newbery contender, even as the final book in a series.

I usually don’t read past the first book in a series. I just don’t have time with all the great books out there calling for my attention, but I find myself drawn to these characters.