new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: new_voice_2016, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 24 of 24

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: new_voice_2016 in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsJoAnne Stewart Wetzel is the first-time novelist of

Playing Juliet (Sky Pony, 2015). From the promotional copy:

Beth Sondquist, 12 1/2, secretly dreams of playing William Shakespeare’s Juliet. When she learns the children’s theatre in her town is threatened with closure, she and her best friend, Zandy Russell, do everything they can to save it. But since Beth keeps breaking one theatre superstition after another in the process, she may never get onstage again.

Quotes from Shakespeare bookmark each chapter and foreshadow the next plot twist as a multicultural cast of kids fights to keep their theatre open.

Could you describe both your pre-and-post contract revision process? What did you learn along the way? How did you feel at each stage? What advice do you have for other writers on the subject of revision?I love to revise. When I started my first novel, Playing Juliet, I worked on the first chapter for months. It was polished and perfect before I went on to the second chapter.

But by the time I had finished the first draft, the characters had changed, the plot had changed and I had to throw the whole first chapter out.

When the draft was finished, a New York editor read the first ten pages at a

SCBWI conference. Of course I was expecting her to offer to buy it on the spot (don't we all) or at least to ask to see the full. Instead, she said she didn't find my main character, Beth, charming.

Charming? A 12-and-a-half-year-old narrator focused on getting onstage while her costume was falling apart had other things to worry about besides being charming. But I read over the chapter carefully. While Beth's focus was appropriate, was she a little self-centered? What if I had her do something for someone else?

|

| Inspiration! Just So Stories, Palo Alto (CA) Children's Theater |

I added exactly six sentences to an early scene that showed the cast waiting in the wings to go on. Beth notices that a younger actor playing a mouse is nervous, remembers that it's the Mouse's first play and that she'd seen her reapply her make-up in the dressing room at least four times.

Though they have to be very quiet backstage, Beth whispers, "Great nose." and outlines a circle on her own.

Sometimes it only takes six sentences. When the book was published, the review in the School Library Journal began "In this charming story featuring a relatable narrator and action-driven plot..." A blurb by the author Miriam Spitzer Franklin ended by saying the book "introduces a protagonist who will steal your heart as she chases after her dreams."

Another reader pointed out that while Playing Juliet started with lots of references to the superstitions around MacBeth and ended with a production of Romeo and Juliet, a few of the earlier chapters had almost no reference to Shakespeare. Was there a way to weave him into the rest of the book?

There was no room to introduce another play into this middle-grade story but I'd always loved reading books with epigraphs. Could I find enough quotes from Shakespeare's writings to serve as appropriate epigraphs before each chapter?

I used the

Open Source Shakespeare search engine, typed in a word like "jewel" or "duchess" and got a list of all the appearances of these words in his works. The perfect epigraph kept jumping out at me.

For the chapter in which the kids are looking for a lost diamond bracelet, I quoted "Search for a jewel that too casually Hath left mine arm" from

"Cymbeline.""What think you of a duchess? have you limbs to bear that load of title?" from

"Henry VIII" made the perfect epigraph for the chapter in which Beth is asked if she can cover the part of a Duchess for an actor down with the flu during the run of "Cinderella!"

|

| Joanne & daughter seeing Royal Shakespeare Co. |

I was excited when an editor told me she'd brought the manuscript to committee, even when she added that they'd like to see a rewrite. They were uncomfortable with a scene in which Beth and two of her friends sneak out at night to break into the Children's Theatre.

I loved that scene. It was scary and exciting and the kids had the best of intentions. But I could make the plot work without it, so I took it out.

That editor didn't take the book. The next two editors it was sent to both commented that they felt the story was too quiet.

I put the scene back in. It wasn't necessary to the plot but it was vital to the development of the characters, for it showed what they would sacrifice to save their theater. The book sold right after that scene was restored.

I've brought all of the lessons I learned writing my first novel to the next one I'm currently working on. I'm going to finish the whole manuscript before I start to revise.

I will honor each critique I get, and find a way to solve any problem that's been identified. It could lead to a much richer book and may only take six sentences. But I will also evaluate how the changes have affected the story and if they don't help, I'll change it back.

Post-contract Revision Process |

| Sis-in-law, Elephant Cafe, Edinburgh |

When Julie Matysic at Sky Pony Press acquired the manuscript, she sent her editorial comments to me in a Word document. I had the chance to approve, change or comment on the suggested changes. Most of the revision was copy edits and most of the time I couldn't believe I'd let such a glaring grammatical error slip through.

But one set of edits I disagreed with. I had capitalized the names of all the characters in the two plays that are performed in the book. The copy editor kept all the proper names—Juliet, Romeo, Cinderella— as I wrote them, but changed all the animal characters—the cat, horse, mice—to lower case.

I decided to email Julie to ask if I could change them back. She said yes, and suggested that since many of the parts were names that would not normally be capitalized, I make up a list of all the characters for the copy editor to work with. I'm so glad I asked for clarification.

Remember that you and your editor are working toward the same goal: to make your manuscript great. And you know she has impeccable taste: she picked your manuscript to publish.

Post-contract BonusJulie suggested I do a mood board for the cover. I'd never heard of this but she explained that all I had to do was open a PowerPoint file and create a collage using the covers of books that I like then include a second page with a written explanation of why I had chosen the images. It might be the font, the color, the mood or a combination of all three. When it was done, she would send the collage to the artist creating the design to use for inspiration.

It was so much fun to search through online bookstores to find covers I liked. Beth, my 12-year-old heroine, is threatened with losing the children's theater she has been performing in for years, but I didn't want the cover to be sad.

I wanted it to be a reminder of what Beth loves about theater, about being on stage and what she will lose if her theater closes.

The mood I wanted was joy, the joy of acting, of being onstage. The covers that showed images of flying, fairies, a figure with fantastically long fingers, captured the unlimited world the stage offers.

Because so much of the story takes place in a theater, I was drawn to covers that featured theater curtains opening. Three of the twelve covers I chose had a frame of red theater curtains and two others repeated that shape and color in the clothing of the women depicted: a partially open red coat, billowing red bell bottoms. That rich red set the color pallet that dominated my collage.

When Julie sent me the final cover, I opened the attachment with some trepidation. Up popped a design with a frame of rich red curtains opening onto a dark background that showcased the title of the book. And my name was in lights, just like on a Broadway marquee.

I loved my cover. And the Children's Books manager at

Keplers, my local independent bookstore, told me the cover was so effective, the book was jumping off the shelves. My mood board had worked.

How have you approached the task of promoting your debut book? What online or real-space efforts are you making? Where did you get your ideas? To whom did you turn for support? Are you enjoying the process, or does it feel like a chore? What advice do you have on this front for your fellow debut authors and for those in the years to come? |

| Shakespeare puppets & stamp for JoAnne's signing |

When the

Royal Shakespeare Company announced it was devoting 2016, the year of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death, to celebrating him and his work, I knew I had a great tie-in with Playing Juliet.

When I was in Stratford-upon-Avon last summer, I took a lot of pictures of the buildings that were standing when Shakespeare lived there to use on my web site and in my talks.

I also bought three Shakespeare puppets: a regular hand-puppet for most of my presentations, an elegant figure in a cloth-of-gold costume to use with a sophisticated audience and a finger puppet, because sometimes a smaller figure will just work better.

When I got home, I ordered a Shakespeare stamp to use at my book signings. After all, the Bard wrote all of my epigraphs.

I've struggled to get my web pages up. I have now checked off a

web page for myself, with all of my books on it, and a web page for

Playing Juliet with links to 13 Superstitions Every Theater Kid Should Know as well as links to photos of Shakespearian sites at Stratford-upon-Avon.

I've got an author's page on

Amazon and

Goodreads and

SCBWI. I did a Launch Page on the new SCBWI web program. This all took a very long time.

|

| Author/illustrator guest book, New York Public Library |

Kepler's Bookstore, has been a great help. They invited me to have my book launch party there, which, on their advice, was held a week after the pub date because every now and then, books are delayed. The copies of Playing Juliet arrived on time but I was happy to have the extra week to prepare for the talk.

Kepler's is still supporting me. Want a signed or inscribed copy of my book? Just order it online from them.

I worked with my publicist at Sky Pony Press to have her send copies of the books to the winner of the giveaways I ran on Goodreads and to my alumni connections.

This resulted in a featured review, with a color picture of the cover of the book, in the ASU magazine, which is sent to 340,000 people.

So far I've spoken at an event at our local library, at my grandsons' school in Ghana, and sold copies at our regional SCBWI conference. I'll be talking at other schools in the fall. When I was in New York City recently, I introduced myself to the librarians at the Children's Room at the New York Public Library, and was invited to sign the guest book they keep for visiting authors and illustrators.

And online I've been invited to do an interview on Library Lions and Cynsations.

I've been enjoying the process, but it takes a lot of time and I'm impatient to dive into my next middle grade.

|

| the Lincoln Community School in Accra, Ghana |

What advice do you have on this front for your fellow debut authors and for those in the years to come?Start early. Well before your pub date, get your author's pages up on SCBWI, Amazon and Goodreads. Figure out how the book giveaways on Goodreads work, and think about posting one before your book is out. Don't wait until your book comes out to publicize any good news about it.

Jane Yolen wrote the most incredible blurb for Playing Juliet, saying "I couldn't stop reading," but I waited until the book came out to share it with everyone. I'm not making that mistake again.

My next book, My First Day at Mermaid School, is a picture book that will be coming out from Knopf in the summer of 2018 and

Julianna Swaney is bringing her amazing talent to the illustrations.

Cynsational Notes |

| Waylon, writer cat |

JoAnne's other publications include:

- Onstage/Backstage, with Caryn Huberman (Carolrhoda, 1987);

- The Christmas Box (Alfred A. Knopf, 1992);

- and My First Day at Mermaid School, illustrated by Julianna Swaney, (Alfred A. Knopf, Summer, 2018).

In Playing Juliet, Beth continually quotes the web page, "13 Superstitions Every Theater Kid Should Know," which can be found on

www.playingjuliet.com. This site also includes photos of Shakespearian sites in Stratford-upon-Avon (see below).

Cynsational GalleryView more

research photos from JoAnne.

|

| Shakespeare's Childhood Home |

|

| Shakespeare's Childhood Bedroom |

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsKatie Kennedy is the first-time author of

Learning to Swear in America (Bloomsbury, 2016). From the promotional copy:

An asteroid is hurtling toward Earth. A big, bad one. Maybe not kill-all-the-dinosaurs bad, but at least kill-everyone-in-California-and-wipe-out-Japan-with-a-tsunami bad. Yuri, a physicist prodigy from Russia, has been recruited to aid NASA as they calculate a plan to avoid disaster.

The good news is Yuri knows how to stop the asteroid--his research in antimatter will probably win him a Nobel prize if there's ever another Nobel prize awarded. But the trouble is, even though NASA asked for his help, no one there will listen to him. He's seventeen, and they've been studying physics longer than he's been alive.

Then he meets (pretty, wild, unpredictable) Dovie, who lives like a normal teenager, oblivious to the impending doom. Being with her, on the adventures she plans when he's not at NASA, Yuri catches a glimpse of what it means to save the world and live a life worth saving.

Prepare to laugh, cry, cringe, and have your mind burst open with the questions of the universe.How did you approach the research process for your story? What resources did you turn to? What roadblocks did you run into? How did you overcome them? What was your greatest coup, and how did it inform your manuscript?Research was a huge part of writing

Learning to Swear in America. The book is about an incoming asteroid, and the main character, Yuri, is a physics genius. I’m not.

I knew I didn’t want the book to be science-free. I mean, how could it be? It would be like a biography of a poet that doesn’t talk about the poetry—it would be missing a crucial element.

A physician friend told me about a Morbidity & Mortality meeting he attended as a young doctor. The physician in charge strode out onto the stage and wrote on the marker board:

- I didn’t know enough.

- Bad stuff happens.

- I was lazy.

The man turned to the assembled doctors and said, “The first two will happen. You will have patients die for both those reasons.”

Then he slammed the side of his fist against the board and roared, “But by God it better never be because you were too lazy to Do. Your. Job.”

That’s how I felt about approaching research for Learning to Swear. I didn’t know enough. I would make mistakes. But it wouldn’t be for lack of trying.

I read

Neil deGrasse Tyson,

Brian Greene,

Michio Kaku, and articles written by astrophysicists—for astrophysicists. You can find science simplified for the average educated reader—the basics on asteroids, for example. But if you want simplified information on spectral analysis? Forget it.

NASA’s website has all sorts of tables about asteroids, and it was a go-to source—until I discovered that the government shutdown also shuttered NASA. It was inconvenient not to be able to access information on which I was used to relying. It was chilling to realize that the people who usually stand sentry for Earth had been pulled in.

I should mention that a physicist who’s involved in security issues read for me—this is Dr. Robert August—and did me a world of good. Not only did he help me get the equipment right, but he corrected me on little cultural things. For example, he said that the computer programmers would have the name of their favorite pizza place written on their marker board. I included that.

Almost everything in the scenes with the programmers came from information Bob shared. He’s been in these kind of meetings, so that was incredibly helpful.

My biggest problem—outside of lack of background knowledge—was that I had envisioned exacerbating the problem mid-book by having the asteroid’s speed increase, so that it would arrive sooner than they expected.

Then I discovered this would violate the laws of nature.

Stupid laws of nature. By this point I had half the book written, and knew I had to find another way to make it harder for Yuri to stop the asteroid.

So I ate a lot of mint chocolate chip ice cream and did more reading—and somewhere in the tiny print I found my answer.

I did a little happy dance, and my husband asked why. “I found a way for an asteroid to smash the Earth, and we couldn’t do anything to stop it!”

He gave me a very strange look.

As a teacher-author, how do your two identities inform one another? What about being a teacher has been a blessing to your writing?Learning to Swear in America is based on an

Immanuel Kant quote:

"Do what is right, though the world should perish."

I teach college history, and we talk about Kant as part of the Enlightenment. That quote is one that hooked my imagination—I remember walking across the college parking lot thinking,

Yeah, but what if the world really would perish? What then?This book is the outgrowth of my conversation with Kant about that.

So I think being an instructor is helpful in several ways. First, history is narrative--essentially I tell stories to my students. Some of them are pretty good!

|

| Charlemagne and Pope Adrian I. |

I look at the names in my lectures—the

Gracchi,

Charlemagne,

George Washington—and I’m so grateful that I get to share their stories with my students. What a privilege!

Also—what good practice in storytelling. I get to see immediately when the students’ attention flags.

Second, I come in contact with interesting material all the time, through reading in support of my day job, and even through my own lectures—like the Kant quote.

In fact, the main character of my next book was inspired by an historical figure—but I’m not saying who it is.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsTracy Edward Wymer on

Soar (Aladdin, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Seventh grader Eddie is determined to honor his father’s legacy and win the school science fair in this fun and quirky debut novel.

Eddie learned everything there is to know about birding from his dad, including the legend of the Golden Eagle, which Dad claimed he saw once down near Miss Dorothy’s pond. According to his dad, the Golden Eagle had wings wider than a creek and talons the size of bulldozer claws. But when Eddie was in sixth grade, Dad “flew away” for good, leaving Eddie on his own to await the return of the elusive raptor.

Now Eddie is starting seventh grade and trying to impress Gabriella, the new girl in town. The annual seventh grade Science Symposium (which Dad famously won) is looming, and Eddie is determined to claim the blue ribbon for himself. With Mr. Dover, the science teacher who was Dad’s birding rival, seemingly against him, and with Mouton, the class bully, making his life miserable on all fronts, Eddie is determined to overcome everything and live up to Dad’s memory. Can Eddie soar and make his dream take flight? Was there one writing workshop or conference that led to an "ah-ha!" moment in your craft? What happened, and how did it help you?Three words.

Linda. Sue. Park. I took her writing workshop at the SCBWI-Los Angeles Summer Conference two years in a row. Back then, the workshop was embedded in the other four conference days. The workshop was one hour a day for four days.

Linda taught us how to focus on scenes instead of chapters or plot points. She told us about the “magic camera” that follows the main character everywhere in the story. If that camera stops, then your reader “stops” too. She talked about narration versus dialogue, and how to measure those in your manuscript, while finding the proper balance.

I think you get the picture here. Linda Sue Park is a master storyteller. I learned

a lot of deeper level writing techniques from her.

I’d say to anyone looking for a community of writers, SCBWI provides a wealth of opportunity. Not only do the conferences offer sound advice and suggestions to writers and illustrators about the craft and business of publishing, but there is also great potential to meet writers who will become your friends, mentors, and critique partners.

As a teacher-author, how do your two identities inform one another? What about being a teacher has been a blessing to your writing?I have been an educator for 15 years, at the same school. I have experience teaching elementary and middle school students. Now I’m an assistant principal.

I love my job. I love being around young people who are learning at breakneck speeds. I especially love being surrounded with their enthusiasm for reading.

Ages 8-12 are the golden years of reading, and it’s no coincidence that I ended up writing stories for that age group.

I began reading a lot around the same age, and authors like

Roald Dahl have a special place in my heart, and I’m sure many other adult readers feel the same way. The best part of being an educator is being at the center of book-loving teachers, librarians, and students all the time.

My years of teaching led me to read all kinds of authors. I quickly fell in love with authors like

Jerry Spinelli,

Lois Lowry, and

Gary Schmidt. My literary tastes have always sided with realistic fiction, and I’m lucky to have found these authors early on in my writing journey. I still prefer realistic fiction, and there are always new voices hitting the scene.

This year, I’m lucky to be one of those voices.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsJenn Bishop is the first-time author of

The Distance To Home (Knopf, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Last summer, Quinnen was the star pitcher of her baseball team, the Panthers. They were headed for the championship, and her loudest supporter at every game was her best friend and older sister, Haley.

This summer, everything is different. Haley’s death, at the end of last summer, has left Quinnen and her parents reeling. Without Haley in the stands, Quinnen doesn’t want to play baseball. It seems like nothing can fill the Haley-sized hole in her world. The one glimmer of happiness comes from the Bandits, the local minor-league baseball team. For the first time, Quinnen and her family are hosting one of the players for the season. Without Haley, Quinnen’s not sure it will be any fun, but soon she befriends a few players. With their help, can she make peace with the past and return to the pitcher’s mound?

Was there one writing workshop or conference that led to an "ah-ha!" moment in your craft? What happened, and how did it help you? After querying two projects and having plenty of full requests but no offers, I felt stuck in that place I'm sure many other writers have found themselves in. You're so close, but still not there yet.

There's something holding you back, but no one has been able to articulate it. And since you're the writer, you don't have the capacity to objectively evaluate your own finished product. Of course the story works for you; you wrote it!

It was at this point in my writer's journey—after feeling frustrated with being so close and still not there yet, that I applied to

Vermont College of Fine Art's MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

The ah-ha moment for me came during the first residency, and was followed by many ah-ha moments in the subsequent ones.

In workshop, each time we met, two writers had their work critiqued by the group. You might think my ah-ha moment came during my own critique, but as I remember, it came from looking closely at the work of my peers.

Suddenly, it started to click—what all those agents had been trying to tell me, but which I had failed to see. I wasn't letting the reader along on the journey with the character, not entirely.

You see, on the surface there was nothing wrong with my writing. Like so many English lit majors, I knew how to write at the sentence level. But what I didn't know—what I was only just beginning to learn—was how to tell a story. Maybe still that language is not perfectly precise.

What I was failing to do was let the reader in on the journey of the story. I was trapping the reader outside of it; it wasn't a lived, breathed experience for them.

I could see this difference as I read my peers' work. Some of us were still in the same stage as me; perfectly suitable writing, but not a lived experience. And others, with interiority and voice, had allowed the reader to become an active participant in the story.

Later in the program,

Rebecca Stead came as a visiting writer and lectured on this participant quality. She spoke of how writing is providing the 2+2 of the equation, and letting the reader put that together to make four.

Like so many beginning writers, I was always writing out the full equation. Not letting the reader to inhabit the story and do the work.

This revelation was one that shook the big picture. It didn't allow for an easy or quick fix. What it meant was that I had to start all over in my thinking of how to tell a story, what to share with the reader and how.

Like so many things in writing, it was just the beginning.

As a contemporary fiction writer, how did you deal with the pervasiveness of rapidly changing technologies? Did you worry about dating your manuscript? Did you worry about it seeming inauthentic if you didn't address these factors? Why or why not? Coming from a librarian background, I tend to have the long haul in mind. The truth is most books will have longer shelf lives in libraries than they ever will in a bookstore. Who wouldn't want their book to be serendipitously discovered by a teen three, five, ten years after it was published?

As a teen librarian, I assessed the teen fiction collection annually, having to—gulp—discard the books that were no longer circulating to make room for new books.

In truth, some books don't have a long shelf life because they are so technology-obsessed that they date themselves within a few years.

As a middle grade writer, I have it a little easier than YA authors, with technology being not quite as big a part of a ten-year-old's life. That said, there are certain technologies that don't seem to be going away, and it's not in my interest to avoid anything my characters would be using in real life.

In The Distance To Home, text messaging plays a key role in the plot. While I'm a little wary of using branded applications, like Facebook and Twitter, whose purposes and uses have evolved quite a bit in the past five years, it's important at the end of the day to be true to your reader's world.

Anytime you avoid their reality, you risk the chance of a reader feeling jolted out of the story by something that feels inaccurate or false.

|

| This revision kitty always rests on freshly printed manuscripts. |

|

| Christina & kiddos |

By

Erin Petti &

Christina Soontornvatfor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsToday Erin and Christina talk about their new releases and lives as newly published authors. Then offer tips as to how to survive and thrive your literary debut experience.Erin Petti is the first-time author of

The Peculiar Haunting of Thelma Bee (Mighty Media, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Eleven-year-old budding scientist Thelma Bee has adventure in her blood. But she gets more than she bargained for when a ghost kidnaps her father.

Now her only clues are a strange jewelry box and the word "return," whispered to her by the ghost.

It's up to Thelma to get her dad back, and it might be more dangerous than she thought--there's someone wielding dark magic, and they're coming after her next.

Christina Soontornvat is the first-time author of

The Changelings (Sourcebooks, 2016). From the promotional copy:

All Izzy wants is for something interesting to happen in her sleepy little town. But her wish becomes all too real when a mysterious song floats through the woods and lures her little sister Hen into the forest...where she vanishes.

A frantic search leads to a strange hole in the ground that Izzy enters. But on the other side, she discovers that the hole was not a hole, this place is not Earth, and Hen is not lost.

She's been stolen away to the land of Faerie, and it's up to Izzy to bring her home.

CHRISTINA:

The Peculiar Haunting of Thelma Bee (Mighty Media, 2016) hit the shelves this fall. Has life changed for you now that you are a published author?

ERIN: Life is busier now with events and all that good stuff, but I wouldn't trade it for anything.

Also, it's totally and completely amazing to walk into a bookstore and see something I wrote on the shelves.

Pretty much a lifelong dream come true!

CHRISTINA: Yeah, seeing my book on the shelf is still kind of a shock. When friends snap a photo of

The Changelings (Sourcebooks, 2016) in a store halfway across the country, that’s when it hits me that all of this really happened.

Because otherwise life isn’t too different, you know?

It’s not like publishing a book gets you out of doing the laundry or the dishes! And meanwhile I can’t help putting even more pressure on myself to write the next thing.

ERIN: Oh absolutely, but writing that next thing is exactly what you have to do. That’s the biggest piece of advice I share with writers who are querying or about to debut - "keep writing!"

It took me a long time to write, revise, and query and there were moments where it was hard to get back to the actual writing part.

But the writing is really all you have control over so as long as you're creating and getting words on the page, you're doing your job.

|

| Erin |

CHRISTINA: That’s a good reminder – the author’s job is to write the books!

And you’re so right – there is a lot you don’t have control over, which can be stressful but also liberating in a way.

Speaking of “jobs,”you have a young daughter and another baby on the way as well as other work that you are passionate about.

How do you juggle life and writing?

ERIN: It's not super easy to schedule, and I've definitely had a measure of trouble keeping the house clean and my kid’s shoes on the right foot - but we're getting by.

My husband is more or less super-dad, and I rely on him an awful lot. But you are one to talk with your own work and two young kids!

CHRISTINA: Well, meeting other writers – like you – who have similarly jam-packed lives has been good for me. It’s a reminder that the vast majority of us have to purposefully and doggedly carve time out from our crazy lives to write, even after we get published.

Some days I get a couple hours, other days just enough time to jot down notes. But I’ve found that if I don’t write every day I get into trouble, and it’s harder to pick it back up. Oh, and I definitely gave up on having a clean house years ago!

Readers are going to fall in love with

The Peculiar Haunting of Thelma Bee. Your book isn't just for the Halloween season, but it definitely explores the paranormal.

Do you have a favorite spooky scene from the book?

ERIN: One of my favorite scenes is when the three young heroes are walking alone through the cold, dark New England woods searching for a certain (possibly haunted) cottage.

I got to play with the environment a lot--exploring just what is lurking in those tall shadows--and it really shows the kids at their bravest.

CHRISTINA: And those illustrations really build the suspense! They remind me of

Edward Gorey’s drawings, which I totally love.

ERIN: I love the illustrations, too! We’ve both talked about how we lucked out with our books’ art. Your beautiful cover jumps off the shelf! It definitely gives you the feeling that these fairies are no Tinkerbelles, that there is something darker going on.

CHRISTINA: Yes, the story was inspired by old folktales of fairies who steal babies and swap them with Changelings, so definitely a little dark. Their motivation for doing that was one of the most fun things to explore in the book. Why would they want human babies? And why would a Changeling sign up for that exchange?

Tips for Debut Authors1. Enjoy the moment: As much as we hate to start things off with a sentiment that should be cross-stitched onto a pillowcase, this one happens to be very true.

Celebrate the big and small milestones – your first signing, seeing your book on the shelf for the first time. And then there will be a moment when a reader loves your book so much that they tell you.

Soak that in. Don't skim over the beautiful moments. You only do this debut thing once.

2. Connect with a community: Other authors are the best and most supportive people to have in your corner, and sometimes the only way to maintain your sanity.

Twitter, conferences, and debut groups are wonderful ways to connect with other debut authors who are going through the same ups and downs as you are.

It also feels so satisfying to cheer on their successes and root for people whose books you love.

3. Turn that dang thing off: Social media can help keep you connected when you need it. But it can also suck the hours right out of your day – and time is going to be your most precious resource when your book comes out.

So as much fun as it is to chat and retweet clever

"Stranger Things" gifs, know when to put down the phone and work/read/rest.

Social media can sometimes also make you feel like everyone in the world is getting a book deal/winning awards/getting a movie contract/selling millions of copies – everyone but

you. If you ever feel that way, turn off that app for a little while, and see Tip #2.

4. Make it easy on your publicist: Your publicist will be your ally in helping to set up events, pitch you for conferences, and make connections for a blog tour.

But as much as they love you and your book, they will have other authors they are also working with and new books continuously coming down the pipe. Do what you can to help them help you.

During your first meeting or conference call, ask them for concrete ways you can help. Maybe you know of a local area children's book festival that your author friends rave about. Or perhaps your critique partner has a great blog and she wants to do a giveaway for you. Doing your research ahead of time will make everyone's jobs easier.

5. Get ready for things to change: Have you ever gone to a

SCBWI Conference and sat next to a debut author who told you, "Just enjoy the freedom of not being published yet. You can write so unselfconsciously," and you wanted to stab them with the pen that came in your registration tote bag? Turns out there's a little bit of truth to that.

For a lot of authors, getting published creates this paradox of delusional thinking that now they will never be published again. I blame some of this on the overemphasis of "being a debut." and the accompanying feeling that once your debut is over, you are used goods.

But whatever the reason, there are expectations now, real and imagined, from you, your agent, your publisher about you as a professional author. And you may find yourself longing just a little for the days when you wrote just to write, and there was less expectation, less self criticism, more freedom. (But don't say that to unpublished writers at conferences. Those pens are sharp).

6. Get ready for things to be exactly the same: After the initial sparkly, Instagram-worthy swirl of launch date subsides, life is likely going to feel pretty same-ish.

Yes, there may be events and school visits, book signings and festivals. But for most of us, the bulk of our days will carry on as before.

Your non-writer friends will assume you are out shopping for a Tesla Roadster or having brunch with

Ann Patchett when really you are cleaning a lint trap or scraping an exploded baked ziti off the oven door.

If in that moment you think to yourself, "I shouldn't be doing this – I'm a published author," you are in big trouble.

7. Keep writing: The best way to simultaneously get over your anxiety and celebrate your newfound authordom is to write more things.

If you have gotten to this point of having a book published, you must love the work of writing. There is no other reason that a sane person would endure the long, unpaid hours, the sting of rejection letters, the glacial delay of gratification, if that person didn't love to write.

You may have to write more things because you signed a contract for another book. If so, lucky you! But even if that's not the case, start on a new project before your debut comes out. You may have to set it aside during the busy days of your launch, but it will feel so good to open up your laptop and have something ready and waiting for you.

8. Find joy in other things: These things may be hobbies or your day job or your daily walk, or art museums or jiu jitsu. Or they may be people, like your spouse or your friends or your children.

These things matter very much, just as much as writing. And unlike writing, these things will hug you and they will eat your cruddy, over-baked ziti. And when you are having a hard day, they will hold up your new book and smile and say, "Look what you did! You did this!"

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

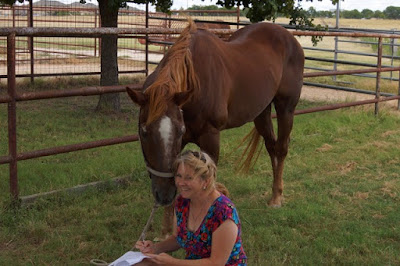

CynsationsDonna Janell Bowman is the first-time author of

Step Right Up: How Doc and Jim Key Taught the World About Kindness, illustrated by

Daniel Minter (Lee & Low, 2016). From the promotional copy:

A Horse that can read, write, and do math?Ridiculous! That’s what people thought until former slave and self-taught veterinarian Dr. William Key, with his “educated” horse Beautiful Jim Key, proved that, with kindness, anything is possible. Over nine years of exhibiting across the country, Doc and “Jim” broke racial barriers, fueled the humane movement, and inspired millions of people to step right up and choose kindness. What was your initial inspiration for writing this book?This question ties so perfectly into my belief that there’s a piece of us in everything we write.

In 2006, I read a

book about Beautiful Jim Key, authored by Mim Eichler Rivas (William Morrow 2005/Harper Paperbacks 2006). It was a given that I would be drawn to a horse book. I grew up on a Quarter Horse ranch, where life revolved around raising, training, and showing horses, and caring for the myriad livestock and other animals. I have always been an animal lover, and I know firsthand how powerful the human-animal bond can be—how the combination of time, trust, and affection can create such synergy that you can practically read each other’s minds.

|

Courtesy of Tennessee State Library and Archives. |

That kind of relationship bonded William “Doc” Key and his horse, Beautiful Jim Key. While the horse was what drew me to the story, I was immediately awed by Doc. His greatest historical contribution was an unmistakable message about kindness, in a time of extreme racial prejudice, and brutal treatment of animals.

How could I not love the story of a man who overcame so much to make a real difference in the world?

Thanks to Doc, “Jim,” the horse, became a sort of poster child for the emerging humane movement, while Doc overcame injustices, broke racial barriers, and helped change the way people thought about and treated animals. Doc was awarded a Service to Humanity Award, and Jim was awarded a “Living Example” award.

So, back to your question, Cyn, about what inspired me to write this story—it spoke to my heart. I dived into research with zeal.

What were the challenges (literary, research, psychological, logistical) in bringing the text to life?There were a number of challenges to writing this story, but three that most stand out:

First, the research. It was claimed that Beautiful Jim Key could read, write, calculate math problems, compete in spelling bees, identify playing cards, operate a cash register, and more. I had to get to the bottom of how this could be possible.

I used the adult book as my jumping off point, but I wasn’t satisfied to rely solely on somebody else’s research.

This is a story that straddles the 19th and 20th centuries, so I read a great deal about the period, including slavery, the Reconstruction Era in the distinct regions of Tennessee, the history of the humane organizations; the related World’s Fairs, Doc’s business interests, etc.

Emotionally, the most difficult part was reading about how animals were treated in the 19th century, and, more importantly, how enslaved people were often treated with similar brutality. Only a tiny fraction of my research appears in the book’s back matter, but it all deeply affected my approach to the story.

I visited the

Shelbyville (TN) Public Library and skimmed through their microfilm. Then I spent some time at the Tennessee State Archives, donning white gloves as I perused the crumbling scrapbooks from the BJK collection.

During that 2009 trip, I also visited the humble Beautiful Jim Key memorial in Shelbyville, TN, and Doc’s grave site at the Willow Mount Cemetery. (I might have shed a few sentimental tears.) We then tracked down what I think was Doc’s former property, though the house is long gone.

This kind of onsite research, along with old photos and local news accounts, allowed me to imagine the setting of Doc’s hometown. Back home, I collected binders-full of newspaper articles, playbills, and promotional booklets. Through these, I got a feel for how people thought about Doc and Jim.

And, most importantly, I found some of Doc’s explanations for how he taught the horse. What became clear was, though we may never know exactly how the horse was able to do so many remarkable things, the countless news reporters and professors who tried to prove trickery or a hoax, never found anything beyond “education.” Jim only rarely made mistakes.

Ultimately, what Doc and Jim did for the humane movement is even more significant than what the horse performed on stage.

Originally, I had planned the story for middle grade audiences until my agent (who wasn’t my agent yet) suggested that I try a picture book version. I already had half of the chapters written by this time, so I was aghast at the thought of starting over. And I didn’t know how to write a picture book biography. I spent the next two years analyzing and dissecting a couple hundred picture book biographies to figure out how they work.

I decided to

blog about some of my craft observations, using the platform as a quasi-classroom for myself and anyone else who might happen upon my site.

Many, many, many drafts later, I had a manuscript that attracted the attention of a few editors. Lee and Low was the perfect home for Doc and Jim.

There was a built-in challenge in writing this story about a formerly-enslaved African American man. Because I don’t fit any of Doc’s descriptors, it was doubly important that I approach the subject with respect and sensitivity.

I couldn’t merely charge through with the mindset that I’m just the historian sharing documented facts.

How are you approaching the transition from writer to author in terms of your self-image, marketing and promotion, moving forward with your literary art?It is so exciting to finally be crossing the threshold into this new role. The past nine years, which is how long I’ve had the story in my head and in my heart, have felt like the longest-ever pregnancy.

There’s a mixture of joy, relief, and fear during this delivery stage. Fortunately, so far, very nice starred reviews have praised the book, and each reviewer wisely sings the praises of Daniel Minter’s spectacular lino-cut acrylic art.

As I think ahead to marketing and promotion, I’m planning for the Oct. 15 release, the Oct. 23 launch party, and how the book might raise awareness of the need for more kindness in the world—not only toward animals but toward each other.

From my very first draft, nine years ago, I knew I’d revive the original Beautiful Jim Key Pledge—originally signed by two million people during Doc and Jim’s time.

I plan to incorporate the pledge into my author presentations, and it will be downloadable from my website soon. I also hope to align with some humane organizations to help them raise awareness.

I have two more books under contract, several others on submission or in revision, and a novel-in-progress.

In 2018, Peachtree Publishers will release En Garde! Abraham Lincoln’s Dueling Words, illustrated by

S.D. Schindler, followed in 2019 by King of the Tightrope: When the Great Blondin Ruled Niagara, illustrated by

Adam Gustavson.

Such is the author’s life, right? We write, we rewrite, we revise, we sell, we wait, we celebrate, then we do it all over again. Because we can’t imagine not writing something that moves us. And we can’t imagine not writing for young people.

Cynsational GiveawayBook Launch! Join

Donna Janell Bowman at 3 p.m. Oct. 23 at BookPeople in Austin. Donna will be speaking and signing.

Fundraiser: Step Right Up and Help The Rescued Horses of Bluebonnet Equine Human Society: "They are horses, donkeys, and ponies that are helpless and hopeless. And they are hurting. The lucky ones land at Bluebonnet Equine Humane Society. Under the loving care of professional staff and volunteers, the animals are medically and nutritionally rehabilitated, then placed with trainers to prepare them for re-homing/adoption." See also

Interview: Step Right Up Author Donna Janell Bowman by Terry Pierce from Emu's Debuts.

Enter to win two author-signed copies of

Step Right Up: How Doc and Jim Key Taught the World About Kindness by

Donna Janell Bowman, illustrated by

Daniel Minter (Lee & Low, 2016).

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsJonah Lisa Dyer and Stephen Dyer are the first-time authors of

The Season (Viking, 2016). From the promotional copy:

She can score a goal, do sixty box jumps in a row, bench press a hundred and fifty pounds…but can she learn to curtsy?

Megan McKnight is a soccer star with Olympic dreams, a history major, an expert at the three Rs of Texas (readin’, ridin’, and ropin’), but she’s not a girly girl. So when her Southern belle mother secretly enters her as a debutante for the 2016 deb season in their hometown of Dallas, she’s furious—and has no idea what she’s in for. When Megan’s attitude gets her on probation with the mother hen of the debs, she’s got a month to prove she can ballroom dance, display impeccable manners, and curtsey like a proper Texas lady or she’ll get the boot and disgrace her family. The perk of being a debutante, of course, is going to parties, and it’s at one of these lavish affairs where Megan gets swept off her feet by the debonair and down-to-earth Hank Waterhouse. If only she didn’t have to contend with a backstabbing blonde and her handsome but surly billionaire boyfriend, Megan thinks, being a deb might not be so bad after all. But that’s before she humiliates herself in front of a room full of ten-year-olds, becomes embroiled in a media-frenzy scandal, and gets punched in the face by another girl.

The season has officially begun…but the drama is just getting started. How did you discover and get to know your protagonist? How about your secondary characters? Your antagonist?The Season is a modern retelling of

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen set in Texas in 2016 so our main character, Megan McKnight, is based on Elizabeth Bennet.

We really examined that classic, well-loved character and asked ourselves: What traits make her who she is? What makes her the woman Mr. Darcy falls in love with? The woman we

all fall in love with?

We literally made a list of important traits: Brash, forms strong opinions, speaks her mind, loves to read, more physically active than other women, witty, fiercely loyal, loves the outdoors, isn't as interested in men as other young women her age, her singularity. Things like that. Then we tried to imagine what a modern young woman, who embodied all those traits, would be like.

We decided she'd be a history major and an athlete and we chose soccer as her sport. She'd be the kind of girl dedicated to practicing and playing even if it meant she was a little intimidating to guys and didn't have much time for dating. She'd be more interested in fueling her body for athletics than in fitting into a size two. She'd throw her hair in a ponytail, put on some Chapstick and pull on track shorts rather than care about makeup and fashion. She'd be funny and snarky, but so much so that it would get her into trouble sometimes. She'd be more loyal to her sister and her teammates than to any guy.

And also, like Elizabeth Bennet, she'd have no idea how to be coy. While other girls (like her sister) might hide their feelings, she just wouldn't be capable of keeping her opinions to herself.

As you can see, we had a really strong blueprint to build our main character from, which is a wonderful. But the kinds of questions we were focused on are no different when you're creating a character from scratch.

I think the most helpful thing with any character is to know where you want them to end up. What lesson must they learn by the end? If the lesson, as in the case of Elizabeth Bennet and our Megan McKnight, is to not form knee-jerk opinions about things, then you better start that character as far away from that point as realistically possible. You have to allow every character, not just your protagonist, room to grow, and change.

A book is not a journey for the reader if it's not a journey for the characters.

And so, the same method applies to all our secondary characters as well. We found modern ways for them to embody the traditional Austen characters' traits. Our Mrs. Bennet is a social climber trying to set he daughters up for success, our Jane Bennet is the embodiment of the perfect young woman, albeit a contemporary one, and our Mr. Darcy is proud and aloof.

Real people always play a role in characterizations, too. Sometimes we think of certain real people that we know or even famous people to help us envision a certain character. I've always found it easier to describe a setting if I've seen it, and the same holds true for people.

Of course, you always add and take away from reality when you're creating fiction, but you often end up with characters who are an amalgamation of people who really exist.

As a comedic writer, how do you decide what's funny? What advice do you have for those interested in either writing comedies or books with a substantial amount of humor in them?Writing comedy is so hard. Humor is in the eye of the beholder and because of this, and perhaps more all other types of writing, it cannot be done in a vacuum.

Like most things having to do with writing, it starts with observation. You know what

you think is funny to you and your friends. Start there. Make notes. Have little booklets full of funny conversations you'd had and witty things you've said. Research isn't just dry reading about some place you've never been or some historical period. Research is about watching human behavior, listening to speech patterns, and being tuned in to what makes people laugh.

Stephen and I have the benefit of having each other. But we had already been together for seven years when we accidentally discovered that we were good writing partners.

I was an actress and was starting to do stand-up comedy in New York City. I was writing my stand-up material and would try things out on him at home in the evenings. He was my sounding board and was almost always able to build on what I had, and make it better.

We started working on all my material together, cracking each other up in the process. It's a really good example of how having a someone to be your sounding board is so important with comedy.

Maybe that's why sitcoms and

"Saturday Night Live" fill hire six-to-fifteen writers who work together or why so many of the old screwball comedies were penned by a two-person writing team.

But even if you don't use a partner to write comedy, you got to find that person or people to give you a gut-check.

To answer the most important question:

Is this funny to anyone besides me?So whether it's your best friend, or an online writing group, or just one other writer who understands your genre, find those Beta Readers.

And if they are good, be good to them. If you can't offer a quid pro quo of also reading their work, then small gifts are a really nice way of saying thank you and keeping them in your corner.

The other important factor in writing comedy is just to do it, and do it often. Your funny bone isn't a bone at all, its a muscle!

Okay, it's really a nerve but that doesn't fit into my metaphor so just go with me. The point is, if you want it to be strong, you have to exercise it! The funnier you are, the funnier you will be. I have never been funnier than when I was doing stand-up because I was doing it every day. My mind was just set to that channel!

If you are writing a comedic piece, you need to immerse yourself in comedy. Hang out with your funny friends! Watch funny shows and movies. Go to a comedy club.

Basically, put yourself in a funny world so you have something to play/write off of.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsJenny Kay Dupuis is the first-time author of

I Am Not a Number, co-authored by

Kathy Kacer, illustrated by

Gillian Newland (Second Story, 2016). From the promotional copy:

When eight-year-old Irene is removed from her First Nations family to live in a residential school she is confused, frightened, and terribly homesick. She tries to remember who she is and where she came from, despite the efforts of the nuns who are in charge at the school and who tell her that she is not to use her own name but instead use the number they have assigned to her. When she goes home for summer holidays, Irene's parents decide never to send her and her brothers away again. But where will they hide? And what will happen when her parents disobey the law? Based on the life of co-author Jenny Kay Dupuis’ grandmother, I Am Not a Number is a hugely necessary book that brings a terrible part of Canada’s history to light in a way that children can learn from and relate to. As an author-educator, how do your various roles inform one another?My roles as an educator and author are intrinsically interconnected. I'm always searching for meaningful, engaging ways to reach out to young people so they can learn more about topics pertaining to Indigenous realities, diversity, social and cultural justice, and respectful relationships.

While working in the field of education, I realized that there were not many children's picture books available that focused on Indigenous realities through the lens of a First Nations family.

Co-writing I Am Not a Number with

Kathy Kacer gave me the opportunity to reflect on the value of literature for young people and how educators and families can make use of picture books to start conversations about critical, real-world issues.

When writing my granny's story, I realized that I was drawing on my expertise as an Indigenous community member, educator and learning strategist. I was cognizant of how children's literature can be used as a gateway to encourage young readers to unpack a story ("community memories"), think critically, and guide them to form their own opinions about issues of assimilation, identity loss, oppression, and injustice; all of which are major themes deeply rooted in policies that have either impacted or still impact Indigenous peoples.

|

| Jenny Kay Dupuis |

A children's picture book like, I Am Not a Number can support educators, students, and families to engage in deep and meaningful conversations.

The story is about my granny, who was taken from

Nipissing First Nation reserve at a young age to live at a residential school in 1928.

The book can be used to direct conversations about not only Indigenous histories, but also the importance of exploring the underlying concepts of social change, including aspects of power relations, identity, and representation. For instance, young readers can engage in a character analysis by exploring the characters' ethics, motivations and effects of behaviours, and the impact of social, cultural, and political forces.

Through strong characters, written words, and vivid illustrations, the readers can also explore aspects of imagery, the settings, and the power of voice (terminology) used to express feelings of strength, fear, loss, and hope.

My hope as an educator-author is that the book, I Am Not a Number, will inspire others to use children's literature to encourage young people to begin to talk about past and present injustices that Indigenous communities face.

How did the outside (non-children's-YA-lit) world react to the news of your sale?I Am Not a Number was released on Sept. 6. The reviews have been overwhelmingly positive in Canada and the United States so far. One of the review sources,

Kirkus Reviews, described it as "a moving glimpse into a not-very-long-past injustice."

Booklist also gave it a starred review and highly recommended it. Other book reviewers have recommended it for teachers, librarians, and families.

As a lead up to the launch of the book, I was asked by various groups (mostly educators) to present either in person or through Skype about topics linked to Indigenous education and the value of children's young adult literature. The sessions have been helpful for the participants to see how a book like I Am Not a Number and others can be used.

The book will also be available in French in early January by Scholastic.

What would you have done differently?  |

| By Jenny's co-author, Kathy Kacer |

A children's book is typically limited to a set number of pages. If more space was permitted, I would have liked to include a short description in the afterword of what happened after my granny and her siblings returned home from the residential school.

In my granny's case, she enrolled in an international private school. The school was located nearby on the shores of Lake Nipissing.

It offered her an opportunity to stay in her community with her family while still receiving an education. Her siblings also each chose their own life path.

What advice do you have for beginning children's YA-writers? How about diverse writers for young people? Native/First Nations writers for young people?Although my first book is a story about my granny who was taken from her First Nations community at a young age to live in a residential school, we need to recognize that there are countless other community stories that need to be told by Indigenous peoples.

My advice for anyone who wants to get started writing children's-YA literature is relatively straightforward.

|

| photo credits to Les Couchi for restoration of the photo |

- Have confidence in your abilities. Start by exploring a topic that you know about.

- Be honest and authentic. Prepare to gather information to ensure the authenticity of the story through an accurate portrayal of the people, place, time period, experiences, language, and setting.

- Be purposeful, thoughtful, and intentional. Take the time to identify what is the intended impact of the story. Writers need to continually ask themselves, "How will the readers be influenced by the characters, language, and overall messaging? How will the reader's view of their own world be expanded?

- Be authentic. Since I Am Not a Number is a children's picture book, it was important that it include authentic imagery. A relative of mine, Les Couchi, had restored a series of old family photos. The old photos helped to inform decisions when communicating with the illustrator, Gillian Newland about the hairstyles, what items to include in my great-grandfather's shop, etc. One of the old photos is included in the book and shows my granny and her siblings outside their house.

- Identify your responsibilities. Sometimes writers from diverse backgrounds have a greater responsibility that includes not just writing the story, but also educating others and transmitting knowledge about cultural, social, political, or economic issues buried within the story. In this instance, I Am Not a Number is not just about a First Nation's girl who was taken to live in a residential school, but it is a story that raises consciousness that Irene (my granny) is one of over hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children impacted by assimilation policies and racialized injustice.

- Be patient and anticipate a lengthy process that may involve information gathering, several rounds of edits, fact checking, searching for the right illustrator, etc. As such, I regularly turned to my family between edits to get their feedback and continued to listen to their memories. Some of the stories included memories of how my great-grandmother often made the best homemade meat pies, baked breads, jams, and preserves.

- Realize that your work is reflection of you. Just because something was done a certain way in the past, does not always make it right today. Be prepared to speak up and ask questions when you feel something does not feel right as you progress throughout the process, especially if you feel it feel it impacts your own ethics and values, or misrepresents a person's/group's racial or cultural identity or nation.

- Discuss participation, consent and consultation. It is essential that publishers who engage with Indigenous authors fully recognize Indigenous expertise and honour the importance of how to respectfully work in collaboration with Indigenous peoples by ensuring their full participation, consultation, and informed consent at all stages.

Cynsational NotesDr. Jenny Kay Dupuis is of Anishinaabe/Ojibway ancestry and a proud member of Nipissing First Nation. She is an educator, community researcher, artist, and speaker who works full-time supporting the advancement of Indigenous education.

Jenny's interest in her family's past and her commitment to teaching about Indigenous issues through literature drew her to co-write I Am Not a Number, her first children's book. The book can be ordered from a favourite bookstore (

Indiebound) and online from

Amazon.ca,

Amazon.com, and

Indigo.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsBridget Hodderis the first-time author of

The Rat Prince (FSG/Margaret Ferguson, 2016). From the promotional copy:

The dashing Prince of the Rats–who’s in love with Cinderella–is changed into her coachman by the Fairy Godmother on the night of the big ball. And he’s about to turn the legend (and the evening) upside down on his way to a most unexpected happy ending! How did you discover and get to know your protagonist?Is it okay for me to say that getting to know Prince Char of the Northern Realm was a bit more like spirit possession than a process of discovery?

One day I was thinking about my dissatisfaction with the story of Cinderella and so many of its modern versions--the weak, passive main character, the inexplicable behavior of her negligent father, the mysteriousness of her stepmother and the insta-love between her and the prince.

Then I kid you not, I suddenly heard a voice in my head.

It was Prince Char, telling me to write his story--the real story. He has a commanding way about him (as befits royalty), and I basically just gave in. I couldn't believe the words that were coming from my fingertips; details that were unique to his way of life, and the person he was, and the upbringing he'd been given at Lancastyr Manor in the Kingdom of Angland.

After that first otherworldly contact with Prince Char, I saw the events in the book as if they were a movie happening in front of me in real time, and I simply described what I saw and heard. It was incredible, exhilarating...and exhausting.

As an autism specialist-author, how do your two identities inform one another? What about being an autism specialist has been a blessing to your writing? Though I'm devoting myself to writing full time now, I worked for many years with children who have various learning differences, primarily on the autism spectrum.

Interacting daily with people who sometimes literally can't speak for themselves has taught me to listen, to pay attention, and be present with others in a much deeper way than I ever did before.

Human beings are wired for quick judgment based on obvious traits, like the way someone speaks or looks. But these things are not the totality of a person; they are the beginning of a story.

If you let others tell you their own stories, in their own ways, rather than making up stories about them in your head, you open up a whole new level of meaning in life.

I think that new awareness helped me go deeper into the point of view of every single character in The Rat Prince. People have asked me how I "figured out" the motivations for personalities on the fringe of the original Cinderella story, like Cinderella's father, and the fairy godmother.

The answer is: I paid attention, and I realized their situations spoke for themselves. Just like with Prince Char, all I needed to do then was write what I heard them telling me.

|

| Bridgit's living room |

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

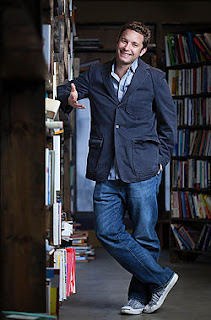

CynsationsChristian McKay Heidicker is the first-time author of

Cure for the Common Universe (Simon & Schuster, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Sixteen-year-old Jaxon is being committed to video game rehab...ten minutes after he met a girl. A living, breathing girl named Serena, who not only laughed at his jokes but actually kinda sorta seemed excited when she agreed to go out with him.

Jaxon's first date. Ever.

In rehab, he can't blast his way through galaxies to reach her. He can't slash through armies to kiss her sweet lips. Instead, he has just four days to earn one million points by learning real-life skills. And he'll do whatever it takes—lie, cheat, steal, even learn how to cross-stitch—in order to make it to his date.

If all else fails, Jaxon will have to bare his soul to the other teens in treatment, confront his mother's absence, and maybe admit that it's more than video games that stand in the way of a real connection.

Prepare to be cured. How did you approach the research process for your story? What resources did you turn to? What roadblocks did you run into? How did you overcome them? What was your greatest coup, and how did it inform your manuscript?This all began when I told my agent,

John Cusick, that I’d write a YA book about a kid committed to video game rehab. His excitement was infectious, and I got that fluttery feeling of embarking on a new adventure. Of darkness unlit. Of stones unturned. Of all the little surprises that come with blindly slashing out with my pen and hoping for the bloody best.

That fluttery feeling vanished when I realized I hadn’t played video games for years, let alone had any clue what it was like to be addicted to them.

In order to survive as a freelance writer, my entire life had become carefully structured to eliminate time-wasters. I worked all possible hours, filled my downtime with reading, exercising, eating healthily, and not buying expensive things like the next generation of PlayStation or Xbox. I had become completely unversed in the world of video games and unhealthy amounts of playing.

I realized if I tried to write a book about video games, I’d out myself as a fraud. I’d make out-of-date gaming references, the community would eat me for breakfast, and I’d become next on

Gamergate’s death list. (Now that I know a thing or two, I can confidently say that many gaming references do not go out of fashion, and that being on Gamergate’s threat list is actually a good thing.)

Let’s face it. As novelists we’re all impostors. We don’t really remember what it’s like to have that first kiss. We’ve never reached to the back of the wardrobe and in place of fur felt pine needles. Our goal is to seem the least impostery as possible. To convince the reader that this stuff is legit.

|

| Christian's office & Lucifer Morningstar Birchaus (aka writer cat) |

Still, the idea was good. Video game rehab? I’d never seen that before, and that’s a rare thing in any medium. So I needed a plan. My plan was this: get addicted to video games.*

So out with work!

Sod off, schedules!

Be gone, exercise routines!

Forget healthy eating and gluten intolerance. Forget that coffee turns me into an absolute monster and dairy turns my insides into the Bog of Eternal Stench!

I bought myself a month and turned my life into that of a sixteen-year-old video game addict on summer vacation. I drank coffee from noon (when I woke up) until three in the morning when I went to sleep. (My character drinks energy drinks, but one can only go so far, dear reader.) I slept too much. I didn’t exercise. Sometimes I put whiskey in my morning coffee. I only read gaming news, but only if I really felt like it and only if I had to wait for a game to download.

Mostly, I played video games. I played a

lot of video games. I continued to play throughout the duration of writing the book, but in October 2012, I played so much it would have made the characters in my book quirk their eyebrows.

I was trying to get addicted. All of my dopamine release came from beating levels, leveling up characters, downloading DLCs. When I went to the bathroom, I brought my iPad with me and played Candy Crush. (Considering what my new and worsened diet was doing to my digestion, I played a lot of Candy Crush.)

I beat Dark Souls. I beat Sword & Sworcery. I played Starcraft and Hearthstone and Diablo III. I bought a Nintendo 3DS and played through all the Mario and Zelda games I’d missed out over all the years. (Definitely the highlight.) I got lost in world after world, and adulthood as I knew it became a faint haze around an ever-glowing screen.

And guess what? It was hard.

You’d think it would be easy doing as little as humanly possible, only filling one’s time with video games.

Video games are fun. Many are designed to keep you falling into them again and again, to captivate you enough to stick around for hours on end. But I had so carefully trained myself to not be that way so I could write.

During this indulgent month of October, I felt lazy. I felt sick. I felt jittery and uncomfortable in my skin and a little voice inside my head kept saying, “No, no, no. Stop doing nothing. You’re dying.”

I was disgusted with myself. I liked the games I was playing, but they didn’t bring the same satisfaction of selling a short story.

Like I said, it was really hard. But it was nothing compared to what I was going to embark on next.

I ended my month of terror with a bang. On Halloween night, at 11:56 p.m., I drank four shots of whiskey and became a vomiting sprinkler on my friends’ front lawn. (Apologies, Alan and Alan).

My girlfriend at the time drove me home and poured me into bed. I slept for thirteen hours. . . and when I awoke late afternoon on Nov. 1, I began something new. I didn’t put on the coffee pot. I didn’t boot up the PlayStation to see if any system updates needed downloading. I didn’t bring the iPad to the bathroom.

Instead, I entered Phase 2 of my research.

The character in my book was going to rehab, where all creature comforts would be taken away from him. And so I spent the entirety of November without sugar, caffeine, music, phone, books*, internet*, or of course, video games.

I called it my no-nothing November.

(Er, no stimulants, at least. But that isn’t quite as catchy.)

After surviving a two-day hangover unaided by stimulants of any sort, I crawled out of bed . . . and I went out into the world. I ran in the morning. I talked to people at coffee shops while sipping herbal tea. I took ukulele lessons. I learned how to cross-stitch. I cleaned Alan’s and Alan’s puke-covered lawn (just kidding I didn’t; I just realized this would have been a nice thing to have done (sorry again, Alans)). I studied life without my nose buried in a book.*

And mostly, I wrote. I wrote about a kid who had all of his comforts taken away and was forced to earn points through a sort of gamified therapy. I don’t know if any of this actually worked or not . . . I’m not sure if it really added anything to the book.

So, um, take that into consideration before flying off the rails for your own book.

*I use the term "addicted" lightly. Read

Cure for the Common Universe for a full explanation.

**The most difficult, by far.

***I also didn’t surf the internet, save my email—for emergencies and so I wasn’t fired from my job.

****Ug, this is starting to sound like some sort of new age instruction manual, which I swear it is not; I just wanted to see what it would be like to be the character in my book.

As a contemporary fiction writer, how did you deal with the pervasiveness of rapidly changing technologies? Did you worry about dating your manuscript? Did you worry about it seeming inauthentic if you didn't address these factors? Why or why not?Video games are the fastest growing medium in the world, so it’s pretty difficult to remain relevant when writing about current games. Fortunately, there’s a persistent spine in gaming (your Blizzards, your Nintendos, your Easter eggs). I tried to focus on those mainstays and accept the fact that no matter what I did I would probably piss off and please an equal number of gamers.

If I had attempted to copy the language of gamers verbatim, I would have set myself up for failure. (Although having a game-addicted roommate during the edits of this book definitely helped me sprinkle in some legit jargon.) That’s why I like to follow the

Joss Whedon rule of leading the charge on language instead of attempting to copy it.

For the dialogue, I ended up stealing a lot of hilarious lines from my friends—truly iconic things that I lifted straight out of real-life conversations and put into the text. During a rousing game of racquetball, a friend aced me, stuck his racquet in my face, and screamed, “Nobody puts princess in a castle!” A barista once mentioned how stepping on a LEGO was a lot more rage inducing than playing Grand Theft Auto. And a previous student told me about a—ahem—particular sensory combination involving Nutella. I blushed . . . and then I stole it.

I stole all of these with everyone’s permission, of course.

By:

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

on 9/26/2016

Blog:

cynsations

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

picture books,

picture book fiction,

Paula Yoo,

Tara Lazar,

Ammi-Joan Paquette,

Kirsten Cappy,

Maria Gianferrari,

new_voice_2016,

Carrie Charley Brown,

Add a tag

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsMaria Gianferrari writes both fiction and nonfiction picture books from her sunny, book-lined study in northern Virginia, with her dog Becca as her muse.

Maria’s debut picture book,

Penny & Jelly: The School Show, illustrated by

Thyra Heder (2015) led to

Penny & Jelly: Slumber Under the Stars (2016)(both HMH Books).

Maria has seven picture books forthcoming from Roaring Brook Press, Aladdin Books for Young Readers, GP Putnam’s Sons and Boyds Mills Press in the coming years.

Could you tell us about your writing community--your critique group or partner or other sources of emotional, craft and/or professional support? In the spirit of my main character, Penny, an avid list maker, here are my top five answers:

1.

Ammi-Joan Paquette:

I am so grateful for my amazing agent, Ammi-Joan Paquette!

Where do I begin? I owe my writing career to Joan, for taking a chance on and believing in me. She has been sage guide, a cheerleader and champion of my writing from the get go.

She’s made my writing dream come true!!

2. Crumpled Paper Critique (CP):

I would not be where I am today without my trusted writing friends and critique partners: Lisa Robinson,

Lois Sepahban,

Andrea Wang, Abigail Calkins Aguirre and Sheri Dillard. They have been such a wonderful source of support over the years, in good times, and in bad.

Yes—it’s kind of like a marriage—that’s how dedicated we are to each other’s work! They’re smart, thoughtful, insightful, well read, hard-working and the best critique partners one could hope for!

We have a private website where we share not only our manuscripts, but our opinions on books, ideas, writing inspiration and doubts. I treasure them and wish we lived closer to one another to be able to meet regularly in person. Hugs, CPers!

3.

Emu’s Debuts: