new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Congo, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 9 of 9

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Congo in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Maggie Belnap,

on 4/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

infographic,

law enforcement,

*Featured,

victor,

Images & Slideshows,

#Cambodia,

Gary A. Haugen,

Locust Effect,

Victor Boutros,

locust,

boutros,

haugen,

imprisons,

Books,

Law,

Current Affairs,

Brazil,

human rights,

violence,

poverty,

Peru,

Congo,

gary,

Add a tag

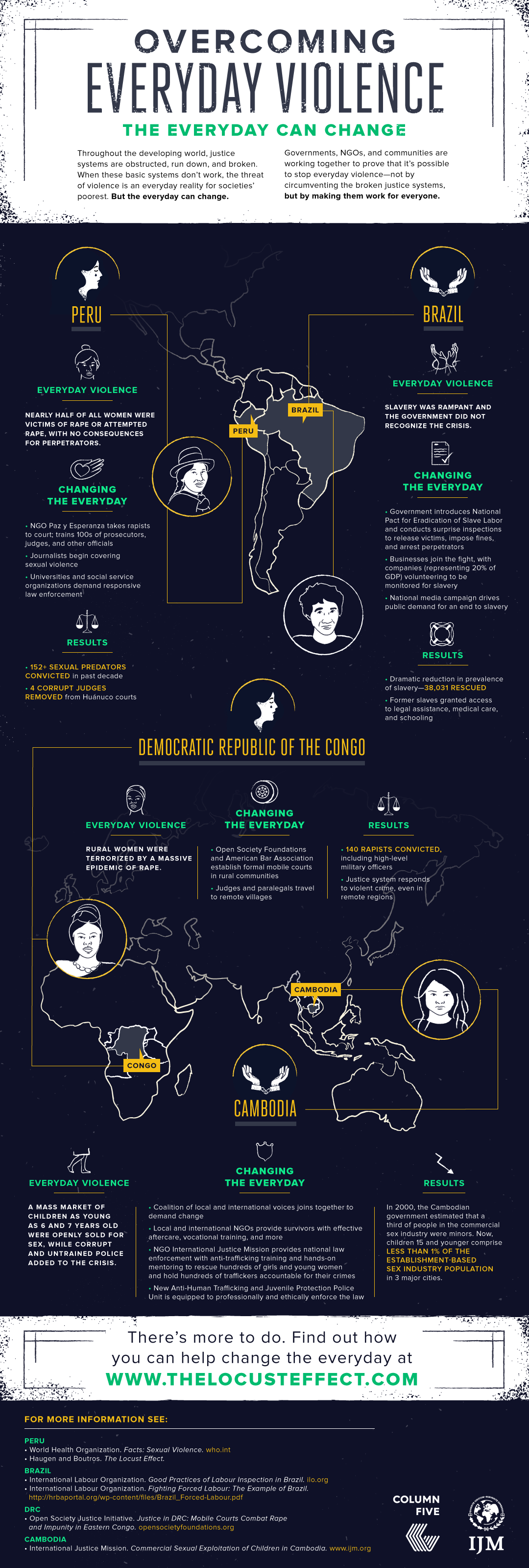

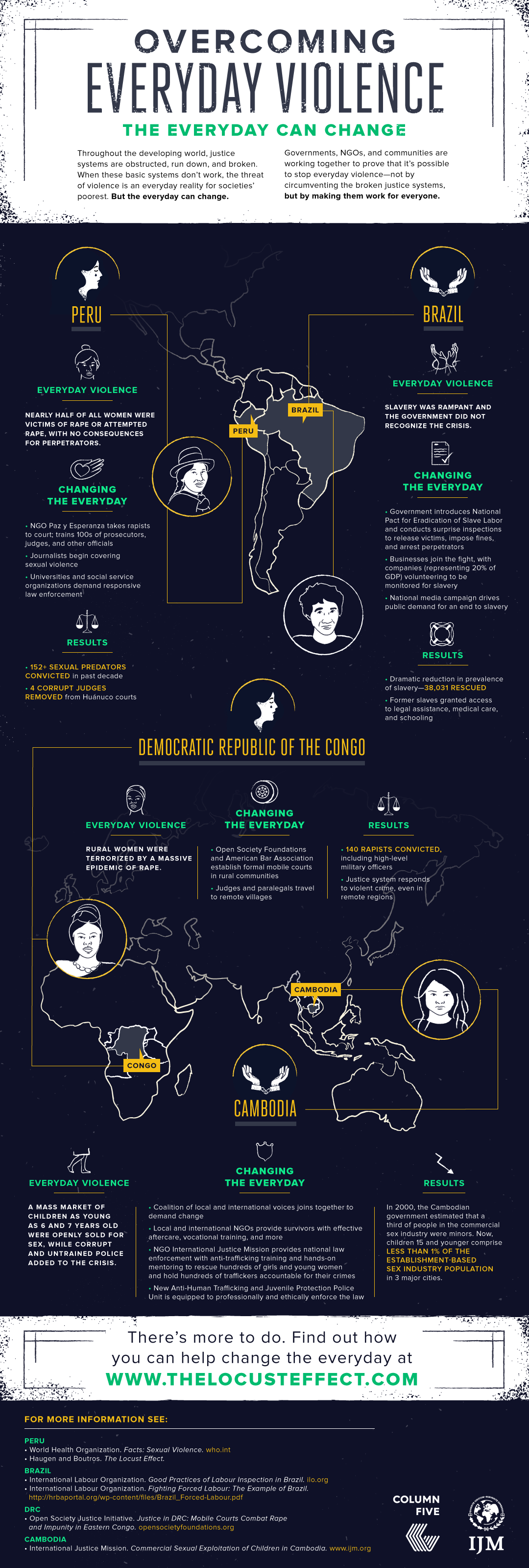

The struggle for food, water, and shelter are problems commonly associated with the poor. Not as widely addressed is the violence that surrounds poor communities. Corrupt law enforcement, rape, and slavery (to name a few), separate families, destroys homes, ruins lives, and imprisons the poor in their current situations. Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros, authors of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, have experience in the slums, back alleys, and streets where violence is a living, breathing being — and the work to turn those situations around. Delve into the infographic below and learn how solutions like media coverage and business intervention have begun to positively change countries like the Congo, Cambodia, Peru, and Brazil.

Download a copy of the infographic.

Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros are co-authors of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence. Gary Haugen is the founder and president of International Justice Mission, a global human rights agency that protects the poor from violence. The largest organization of its kind, IJM has partnered with law enforcement to rescue thousands of victims of violence. Victor Boutros is a federal prosecutor who investigates and tries nationally significant cases of police misconduct, hate crimes, and international human trafficking around the country on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email .or RSS.

The post Overcoming everyday violence [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Africa,

Politics,

Congo,

Tutsi,

hutu,

rwandan genocide,

*Featured,

decolonization,

Burundi,

ethnic violence,

Great Lakes Region,

Gregoire Kayibanda,

J. J. Carney,

Melchior Ndadaye,

Mwami Kigeli V,

Mwami Mutara Rudahigwa,

Rwanda Before the Genocide,

ciat,

Add a tag

By J. J. Carney

A few years ago an American Catholic priest asked me about my dissertation research. When I told him I was studying the intersection of Catholicism, ethnicity, and violence in Rwandan history, he responded, “Those people have been killing each other for ages.”

Such is the common if misguided popular stereotype. But even the better informed are often unaware of the longer historical trajectories of violence in Rwanda and the broader Great Lakes region. Although the 1994 genocide in Rwanda has garnered the most scholarly and popular attention–and rightfully so–it did not emerge out of a vacuum. As the world commemorates the 20th anniversary of the genocide, it is important to locate this epochal humanitarian tragedy within a broader historical and regional perspective.

Northwestern Rwanda by CIAT. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

First, explicitly “ethnic” violence has a relatively recent history in Rwanda. Although precolonial Rwanda was by no means a utopian paradise, the worst political violence occurred in the midst of intra-elite dynastic struggles, such as the one that followed the death of Rwanda’s famous Mwami Rwabugiri in 1895. Even after the hardening of Hutu and Tutsi identities under the influence of German and Belgian colonial rule, there was no explicit Hutu-Tutsi violence throughout the first half of the 20th century.

This all changed in the late 1950s. As prospects for decolonization advanced, Hutu elites began to mobilize the Rwandan masses on the grounds of “Hutu” identity; Tutsi elites in turn encouraged a nationalist, pan-ethnic paradigm. The latter vision may have carried the day save for the sudden July 1959 death of Rwanda’s long-serving king, Mwami Mutara Rudahigwa. Mutara’s death opened up a political vacuum, emboldening extremists on all sides. After an escalating series of incidents in October 1959, a much larger wave of ethnic violence broke out in November 1959. Hutu mobs burned Tutsi homes across northern Rwanda, killing hundreds and forcing thousands from their homes. Scores of Hutu political leaders were killed in retaliatory attacks. Even here, however, motivations could be more complicated than an ethnic zero-sum game. For example, many Hutu militia leaders later claimed that they were defending Rwanda’s Tutsi king, Mwami Kigeli V, from a cabal of Tutsi chiefs. In other cases Hutu and Tutsi self-defense forces collaborated to defend their communities.

Supported by key figures in the Catholic hierarchy and the Belgian colonial administration, Hutu political leaders like Gregoire Kayibanda soon gained the upper hand in the political struggle that followed the November 1959 violence. In turn, political violence took on increasingly ethnic overtones during election cycles in 1960 and 1961; hundreds of mostly Tutsi civilians were killed in a series of local massacres between March 1960 and September 1961. Marginalized inside Rwanda, Tutsi exile leaders launched raids into Rwanda in early 1962, sparking further retaliatory violence against Tutsi civilians in the northern town of Byumba. For their part, European missionaries and colonial officials deplored the violence even as they blamed much of it on Tutsi exile militias, attributing the Hutu reactions to uncontrollable “popular anger.”

If these earlier episodes could be classified as “ethnic massacres,” a larger genocidal event unfolded in December 1963 and January 1964. Shortly before Christmas, a Tutsi exile militia invaded Rwanda from neighboring Burundi. The incursion was quickly repulsed by a combined force of Belgian and Rwandan army units. In the immediate aftermath, the Rwandan government launched a vicious repression of Tutsi opposition political leaders. In the weeks that followed, local government “self-defense” units executed upwards of 10,000 Tutsi civilians in the southern Rwandan province of Gikongoro. Vatican Radio among other media sources deplored “the worst genocide since World War II.” Local religious leaders like Archbishop André Perraudin stood by the government, however, calling the invoking of “genocide” language “deeply insulting for a Catholic head of state.”

Rwanda’s “ethnic syndrome” spread to neighboring Burundi during the 1960s. After a failed Hutu coup d’état in April-May 1972, Burundi’s Tutsi-dominated military launched a fierce repression known locally as the “ikiza” (“curse”). Over 200,000 mostly educated Hutu were killed that summer. In Rwanda, anti-Tutsi violence broke out in February 1973. Although the number of deaths was much lower than in 1963-64, hundreds of Tutsi elites were driven into exile as pogroms broke out at Rwanda’s national university, several Catholic seminaries, and a multitude of secondary schools and parishes.

Rwanda and Burundi were both dominated by one-party military dictatorships during the 1970s and 1980s. For some years each regime paid lip service to a pan-ethnic ideal. However, as economic and political conditions worsened in the late 1980s, ethnic violence flared again in 1988 in the northern Burundian provinces of Ntega and Marangara. In October 1990, the Tutsi-dominated Rwanda Patriotic Front invaded northern Rwanda, sparking a three-year civil war that profoundly destabilized Rwandan society. Following the pattern of the early 1960s, Hutu militias responded by targeting Tutsi civilians in six separate local massacres between October 1990 and February 1994. In turn, the October 1993 assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, Burundi’s first Hutu Prime Minister, sparked a massive outbreak of ethnic violence and civil war in Burundi that would ultimately take the lives of over half a million.

In turn, one should not forget the post-1994 violence that continued to plague the region. Not only did Rwanda suffer more massacres (some directed at Hutu) between 1995 and 1998, but Burundi’s civil war continued until 2006. Perhaps worst of all, Eastern Congo after 1996 became the epicenter of what many scholars have dubbed “Africa’s World War.” The precipitous cause of the conflict was Rwanda’s invasion of Congo in October 1996, ostensibly to clear Hutu refugee camps that were serving as staging grounds for cross-border raids into Rwanda. Upwards of four million Congolese died from war-related causes over the next six years. Over a decade later, Rwandan-backed militias continue to dominate Congo’s Kivu provinces. The “afterlife” of the Rwanda genocide thus continues even in 2014.

The 1994 genocide took the lives of an estimated 800,000 Rwandans, the vast majority of them Tutsi. This genocide–and the world’s utter abandonment of the Rwandan people–should never be forgotten. But nor should we overlook the political and ethnic violence that preceded and followed the genocide, whether in Rwanda, Burundi, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo. One can only hope that the next 20 years will be kinder to a region that has suffered so much over the past generation.

J. J. Carney is Assistant Professor of Theology at Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska. His research and teaching interests engage the theological and historical dimensions of the Catholic experience in modern Africa. He has published articles in African Ecclesial Review, Modern Theology, Journal of Religion in Africa, and Studies in World Christianity. He is author of Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes region appeared first on OUPblog.

Hold a book in your lap and it will take you some place. If you let it take you.

This morning I have sat with Eliot Schrefer's

Endangered, which is to say that I've been living in the Congo. That skittering spectrum of butterflies. That sizzle of manioc and wild garlic. Those high, rattling screams of animals, and of war.

Sophie, our guide, is a teen whose American father lives in Miami, and whose mother has stayed behind in her own country to lead a bonobo sanctuary. In the opening pages, Sophie saves an orphaned bonobo from a cruel fate by buying him from a starving pedestrian. It's not the right way to save this endangered species, but it is the only way, and soon Sophie, now at living for the summer at her mother's sanctuary, becomes this scrawny, mangled Otto's best friend.

Paradise is, however, short-lived. A coup has occurred. All madness breaks out in a part of the world whose mineral resources make it wealthy beyond compare, but whose people have learned to live with little and survive on less. Sophie will have to journey through a war-torn country to safety. She will have to earn the trust of bonobos, find a way to eat, determine what matters most, keep her Otto safe, allow Otto to protect her. She will have to understand love and its limits. Along the way Schrefer's readers come to know a part of the world and a species of animal that deserves our knowing—and attention.

Schrefer comes by his love for bonobos honestly, having spent some time in the Congo himself. (He has the photos to prove it!) He (and his book) exude, as well, great purpose—elevating readerly compassion with a determined heroine, hinting at the complexity of life in a fragile country, making it clear that survival comes, always, at great cost. It's the perfect conversation book, the perfect story for a classroom, the perfect ticket to the Congo.

Three final things:

The photographs above are not of bonobos, but they are the closest I had in my own photo library (images snapped in Berlin last summer).

I loved reading, in the acknowledgments, that my friend and former editor Jill Santopolo had a hand in shaping Eliot's book. Everything that Jill touches sparkles.

If you want to see pictures of Eliot debuting his book at Children's Book World this past Friday, go

here.

One snowy morning in early February, I was sitting on a runway in Cincinnati, Ohio, waiting for the plane to be de-iced before take off, checking emails on my phone. Amongst the mundane messages one leapt out: from Christine McNab of the Measles and Rubella Initiative, the subject line read, "Proposal to travel to the DR Congo/ Illustrate." Through this small device in my hand, I was whisked from the icy Mid-West to Africa, to communities devastated by measles, to children dying in the thousands from this preventable disease. The proposal was very compelling, to visit these communities to talk with families and the immunization workers who travel across the country, often on foot, to distribute the vaccine. And then to draw. To create posters and maybe a book and a video, to communicate the toll of measles and show the ways we can prevent deaths and eliminate this disease.

I could barely wait to get back to New York so that I could say yes. In spite of reading terrible news every day from Central Africa, and in spite of my father's thoughtful links to reports of Congolese plane crashes, there were three insistent reasons to go: 1. I have never been to Africa. 2. I can hear all the news and all the statistics about measles, I can read that 380 children die a day, and yet, as I wave my own healthy children off to school in the morning, I can't possibly imagine the truth of this until I see it. 3. I love my work. I love making pictures that encourage children to turn pages or that cheer up subway commuters, but I've never worked on pictures which might conceivably save lives.

Throughout the past months of conversation and planning, Christine has sent me updates on her work with the Measles Initiative. She has told me about health workers in Nepal who climb mountains to reach remote villages, and immunization campaigns in Myanmar, where the children sit patiently in the shade with circles of bark paste on their faces to cool the skin. Inspired by her beautiful photographs, and because I was itching to get started on this project, I painted this image of a newly vaccinated family.

8 Comments on Africa!, last added: 6/1/2012

By: EDonegan,

on 5/19/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

africa,

Religion,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Media,

World History,

genocide,

Rwanda,

Congo,

Notes From Africa,

Kabila,

Mubotu,

Prunier,

Add a tag

By Eve Donegan, Sales & Marketing Assistant

I thought it would be interesting to provide a quick peek into Gérard Prunier’s thoughts on the history of Congo and the impact of the West. Below is an excerpt from Prunier’s most recent book, Africa’s World War, in which he looks at the history of Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and the events that led up to Africa’s world war.

In many ways Africa was - and remains - the bad conscience of the world, particularly of the former colonialist powers of the Western world. They entertain a nagging suspicion, played up on by the Africans themselves, that perhaps the continent wouldn’t be in such a mess if it hadn’t been colonized. So in the ten years that followed jettisoning the heavy African baggage of apartheid, the international community was only too happy to support the so-called African Renaissance, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development, the New Millennium Goals, and the Peer Review Mechanism of the newly revamped African Union. Within this new paradigm the continental war began as a seemingly bright illustration of the new trend, but then began to evoke an embarrassing reincarnation of some very old ghosts.

Caught in the web of its own tangled guilt - that of having long supported the gross Mobutu regime, combined with the more recent sin of not having helped the Tutsi in their hour of need - the international community tried to hang on to the image of the new Tutsi colonizers of the Congo as basically decent men devoted to making Africa safe for democracy. Of course, there was a bit of a problem factoring in the personality of the leader they had put in power as their Congolese surrogate. It was difficult to smoothly include Laurent-Désiré Kabila in the New Leader movement because the others were reformed communists whereas he was an unreformed one and his democratic credentials were hard to find. So, in a way, when the break occurred in 1998 and the Rip Van Winkle of Red African politics sided with the surviving genocidaires, it was almost a relief: the good Tutsi could go on incarnating Africa’s decent future while the fat Commie could symbolize its refusal to change. The massacre of a number of Tutsi in Kinshasa and the obliging incendiary remarks of the Yerodia Ndombasi helped the international community integrate the new war into its pro-democracy and anti-genocide ideology. But there were lots of contradictions, and it was going to be a harder and harder conjuring trick to pull off as time went on.

Gérard Prunier is a widely acclaimed journalist as well as the Director of the French Centre

for Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. He has published over 120 articles and five books, including

The Rwanda Crisis and

Darfur: A 21st Century Genocide. His most recent book,

Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophefocuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. Living in Ethiopia allows Prunier a unique view of the politics and current events of Central and Eastern Africa. Be sure to check back on Tuesdays to read more

Notes From Africa.

By: EDonegan,

on 2/10/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

africa,

Religion,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Darfur,

Rwanda,

Congo,

Gérard Prunier,

Africa's World War,

Bosco Ntaganda,

Coltan,

Congolese Armed Forces,

Kigali,

Kinshasa,

Laurent Nkunda,

Rwandese Patriotic Army,

Tutsi,

Add a tag

Eve Donegan, Sales and Marketing Assistant

Gérard Prunier is a widely acclaimed journalist as well as the Director of the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. He has published over 120 articles and five books, including The Rwanda Crisis and Darfur: A 21st Century Genocide. His most recent book, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe focuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. Living in Ethiopia allows Prunier a unique view of the politics and current events of Central and Eastern Africa. Below Prunier discusses the involvement of the Rwandan Patriotic Army in Congo.

On the morning of Tuesday January 20th, at the invitation of the Kinshasa government, a column of at least 2,000 soldiers from the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) crossed the border into the Congo towards Goma. This was the first time Rwandese forces had walked on Congolese soil since their evacuation at the end of the war in 2002. Why had they come?

The official purpose was to eliminate the continuing threat posed by the genocidaires remnants of the former Hutu Rwandese regime, the forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), which the Congolese Armed Forces (FARDC) had consistently failed to dislodge. A less visible purpose was to eliminate Congolese Tutsi rebel General Laurent Nkunda who had gotten too big for his breeches and was beginning to embarrass his (un)official sponsors in Kigali. The third – and unacknowledged – purpose was to redistribute the local wildcat mining interests.

Nkundahad fought with the anti-Kinshasa rebels during the 1998-2003 war. But then he had refused to integrate the new national army and claimed to lead a movement to “save the Congolese Tutsi from genocide.” Later, he created his own political movement, the Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP) with the avowed ambition to “liberate” the whole Congo. This began to place him in a rather ambiguous position vis-à-vis his sponsors in Rwanda who did not mind using him to keep a piece of the mining action in Kivu but who certainly did not want to upset the whole international game by attempting to overthrow a legally elected government.

Aware of the fact that Nkunda had only limited support in Kigali, the Kinshasa government attacked him in October of last year but got miserably trounced, given the sorry state of the FARDC. In fact, the whole military-political confrontation was being played out on a background of complex – and contradictory – mining operations. During the war the main source of illegal mining wealth was Columbium-Tantalite(“Coltan”) which had reached very high prices. After 2002-2003 Coltan prices plummeted down due to the massive development of Australian mines. Other minerals (Niobium, Tungsten, Nickel, and Gold) took the place of Coltan. The mines were fairly special: small, illegal, located in hard-to-access places, exploited with very low-tech means, and produced at a very low cost. Kigali agents and FDLR former genocidaires often worked together since FDLR was beyond the pale and the politically correct Tutsi were better able to commercialize the minerals. But this was not a very satisfying solution for the Rwandese regime which ended up sponsoring its enemies. Once it became obvious that the FDLR’s role as a pretext for intervention was getting obsolete, a direct deal between Rwanda’s President, Kagame and Congo’s President,Kabila seemed like a good idea. It would squeeze out both Nkunda (now arrested and replaced by his number two, Bosco Ntaganda) and the FDLR, which would lead to a more beneficial sharing of the mining interests and please the international community. But there was only one problem with this sweet scenario: the Rwandese Army is still hated in the Eastern Congo for the atrocities it committed there during the war. Inviting it in was a very delicate matter.

President Kabila thought he could go over the head of the public opinion, but this is not working very well: the public is incensed at seeing the Rwandese back in the Congo, especially since they were called in by the President they have elected (Kabila’s majority vote came mainly from the East). Extirpating the FDLR might not be as easy as the two Presidents thought. The Rwandese Army is not welcome locally and neither are the violent and undisciplined FARDC. The Rwandese intervention is likely to become another episode of the “post-war war,” not the end of it.

By: EDonegan,

on 2/3/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

pirates,

africa,

Religion,

Politics,

Current Events,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

Media,

Somalia,

Darfur,

Rwanda,

Saudi Arabia,

Congo,

Gérard Prunier,

Blackwater,

Suez Canal,

Ukraine,

Add a tag

Eve Donegan, Sales and Marketing Assistant

Gérard Prunier is a widely acclaimed journalist as well as the Director of the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. He has published over 120 articles and  five books, including The Rwanda Crisis and Darfur. His most recent book, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe focuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. Below is a brief look at the current movements of the Somalia pirates and a proposed alternate way of understanding these so-called “terrorists.”

five books, including The Rwanda Crisis and Darfur. His most recent book, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe focuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. Below is a brief look at the current movements of the Somalia pirates and a proposed alternate way of understanding these so-called “terrorists.”

This piece could be taken as being tongue-in cheek. In fact it should be thoughtfully considered, beyond its apparently provocative aspect.

Since the spectacular seajacking of a Ukrainian transport carrying thirty-three battle tanks heading for Southern Sudan last September 25th followed by the capture of a Saudi tanker carrying $100m of crude oil, the international community has been in a big huff about the notorious Somali pirates operating off the coast of Puntland. They have been called “terrorists” and are now chased by naval units from Germany, France, the United States, China, Australia, India, Russia, Japan, Great Britain, and even Iran. The highly respectable American Enterprise Institute, which in this case seems not to see the original quality of their business initiatives, has declared that “even if ridding Somalia of pirates would by no means solve the country’s problems, it is an absolute first step.” Seven Private Military Companies (PMCs) are on the ranks for the privilege of shooting them with the most advanced technology, including Blackwater of Iraq renown. An energetic blogger is calling for “shooting them on sight.” Their sin? Capturing about 110 ships in 2008 and making $150m in ransom money. The main loss was for the shipping companies, forced to pay higher insurance premiums. If we look more closely at the phenomenon, what do we see?

• Starving young men in small fiberglass boats powered by outboard motors going hundreds of miles from shore on dangerous seas.

• They shoot but try not to kill. So far only one hostage has been shot out of hundreds of seamen taken.

• Many die, like the five man crew who drowned after getting the ransom for the Sirius Star tanker. They lost their lives and their money. One body was washed ashore with $153,000 in his pocket. His relatives put the money to dry. A hard way to keep your family alive.

• Yes, they build big houses, buy shiny cars and sweep beautiful girls off their feet. PMCs operatives who hope to shoot them have fairly similar career plans.

• Those who are captured go to jail, contrary to their militia fellow countrymen on land who murder, loot and rape civilians without any international interference.

Let’s be frank, those boys are no angels. But why focus so much on them? The reason is simple. They cost international business a lot of money, which is absolutely scandalous: Somalis are supposed to kill each other and not come out and tamper with shipping lanes and insurance rates. The Suez Canal Authority is losing millions because of these fellows. Why can’t they get themselves some Toyotas with rocket launchers and join the ranks of the Islamists? If they did, nobody would bother them. But then no more booze, beautiful girls or shiny cars. All they could do would be to pray to Allah and highjack a Red Cross truck, like true Somalis.

By: EDonegan,

on 1/14/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Rwanda,

Central Africa,

Congo,

Gérard Prunier,

Africa's World War,

Lord's Resistance Army,

History,

Religion,

Politics,

Current Events,

Add a tag

Eve Donegan, Sales and Marketing Assistant

Yesterday we posted an essay by Gérard Prunier, the author of Africa’s World War, on the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the effect it has had on the people of Central Africa. Below Prunier answers a few questions that we had regarding the current situation in Africa.

OUP: How has the involvement of the world increased or decreased in Africa since the initial conflict?

Gerard Prunier: I don’t think international involvement of a non-commercial nature in Africa has increased or diminished since the 14 nation war. Basically what you see towards Africa is humanitarian goodwill (of a slightly weepy nature) backed up by celebrity photo ops, journalistic disaster reporting (unfortunately justified), “Out of Africa” type of exotic reporting and diplomatic shuttle diplomacy on Darfur and assorted crisis spots. None of this results in very much action. Meanwhile the United States drinks up crude oil from the gulf of Guinea, India and China export cheap trinkets to the continent and in exchange (particularly China) chew up vast amount of natural resources and build cheap roads and sports stadiums. The Africans at first loved it. Non-imperialistic aid, they said. As the Chinese shoddily-built roads already show signs of wear and tear and as their stadiums and presidential palaces (another Beijing specialty) begin to look slightly out of place, they are beginning to have second thoughts.

(of a slightly weepy nature) backed up by celebrity photo ops, journalistic disaster reporting (unfortunately justified), “Out of Africa” type of exotic reporting and diplomatic shuttle diplomacy on Darfur and assorted crisis spots. None of this results in very much action. Meanwhile the United States drinks up crude oil from the gulf of Guinea, India and China export cheap trinkets to the continent and in exchange (particularly China) chew up vast amount of natural resources and build cheap roads and sports stadiums. The Africans at first loved it. Non-imperialistic aid, they said. As the Chinese shoddily-built roads already show signs of wear and tear and as their stadiums and presidential palaces (another Beijing specialty) begin to look slightly out of place, they are beginning to have second thoughts.

OUP: How has the 2006 election in Congo affected the country?

Prunier: It has stabilized it internationally and tranquilized it internally. But an election is only an election. Phase Two of the Congolese recovery program has so far failed to get off the ground. Security Sector Reform never started (the Congolese Army is still basically a gaggle of thugs who are more dangerous for their own citizens than for the enemy they are supposed to fight), mining taxation is still touchingly obsolete, enabling foreign mining companies to work in the country for a song and a little developmental dance, the political class mostly talks but does not act very much, foreign donors have forgotten the country as it made less and less noise, the Eastern question is a continuation of the endless Rwandese civil war which has been going on with ups and downs for the last fifty years and the sleeping giant of Africa still basically sleeps.

OUP: What sort of future do you see for Central Africa?

Prunier: Only God knows. It will depend a lot on the capacity of the Congolese government to move from a secularized form of religious incantations to real action. Mobutu is dead but his ghost is still with us. One typical feature of Mobutism was the replacement of action by discourse. Once something had been said (preferably forcefully and with a lot of verbal emphasis) everybody was satisfied and had the impression that a serious action had been undertaken. This allowed everybody to relax with a feeling of accomplishment. In a way the last Congolese election was a typical post-Mobutist phenomenon. A very important and valid point was made. This led to a great feeling of satisfaction and a series of practical compromises and lucrative arrangements. The Congolese elite sat back, relaxed and enjoyed its new-found tranquility. Meanwhile the ordinary population saw very little result of this new blessed state of affairs. Beginning to rejoin reality might be a good idea.

OUP: Why do you think the Rwandan genocide and the following occurrences were typically ignored or belittled in comparison to other world catastrophes?

Prunier: I might beg to disagree on that point. For a catastrophe which had no impact on the international community, contrary to 9/11 for example, there was quite a bit of follow-up. The follow-up was in a way easy because it was painless for the international community. Just a little money (very little when one sees the costs of the war in Iraq or of the present financial crisis) and an embarrassed way of looking the other way when President Kagame rode roughshod over the Eastern Congo. Rwanda became a second little Israel, for the same reasons as the first one. Where were we when the people were getting killed? Since we simply had left the question hanging on the answering service, there was a slight feeling of unease when we saw the heaps of dead bodies. As a way of atoning for our sins, we asked somebody else to pay the price of our neglect. The Arabs made a lot of noise about this. But the Congolese had neither oil nor an aggressive universal religious creed. As a result they are still trying to deal with the consequences of our absent-mindedness.

OUP: As someone who resides in Ethiopia part-time, what is the attitude of the country towards the conflict-filled history of Central Africa?

Prunier: Basically the Ethiopians do not care. They have never felt “African” and the only reason Haile Selassie had been able to create the OAU in 1963 is that his country had been the only one in Africa NOT to be colonized. Ethiopia is IN Africa but not OF Africa. Let us forget skin color. Skin color is irrelevant (and many Abyssinians are very light-skinned if one wants to get into that futile line of argument). But let us consider culture. Abyssinia, the old historical core of Ethiopia (i.e. pre 1890), pre-Menelik) is basically an offshoot of the Byzantine Empire, complete with Christian icons, a Monophysite Church, imperial intrigues and forms of writing, worshipping, cultivating, behaving and warring which have almost nothing to do with Africa. Between 1890 and 1900 Emperor Menelik conquered a slice of “real” Africa as a buffer zone against British and Italian imperial ambitions, that’s all. It did not “Africanize” Ethiopia. The average Ethiopian person is much more preoccupied with what goes on in Europe or the US than with what goes on in Angola, the Congo or Nigeria. The only African countries Ethiopia feels vitally implicated with are those of the Horn, of the “neighborhood” so to speak: Eritrea, Djibouti, the Sudan and Somalia. Perhaps a little bit Kenya and Uganda. Seen from Addis Ababa, Rwanda is as far as the moon.

OUP: How do you think the world’s understanding of Africa has changed since the genocide in Rwanda?

Prunier: I don’t think it has changed at all.

OUP: What other books should we read on this topic?

Prunier: In English there are only three: Jean-Pierre Chretien: The Great Lakes of Africa, Danielle de Lame: “A hill among one thousand” and that old classic by Rene Lemarchand:”Rwanda and Burundi” which was published by Praeger in 1970 but which is now out of print. There is a lot of other stuff but it’s all in French.

OUP: What do you read for fun?

Prunier: Milan Kundera, Tony Judt, David Lodge, Edmund Wilson, Nietzsche, Panait Istrati, Chateaubriand, Samuel Pepys, Nicolas Bouvier, Guy Debord, Valeri Grossman, Montaigne, Elmore Leonard, the Duke of Saint Simon, Karl Marx, Dostoievski, Tintin, Jared Diamond, Max Weber, Lord Chesterfield, Balzac, Andre Malraux, Philip Larkin, Witold Gombrowicz, V.S. Naipaul, Bakunin, Orlando Figes, Guillaume Apollinaire, Czeslaw Milocz, the list is endless, I am a very eclectic reader.

By: EDonegan,

on 1/13/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Religion,

Politics,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

genocide,

Sudan,

Darfur,

Rwanda,

Central Africa,

Congo,

Gérard Prunier,

Joseph Kony,

Lord’s Resistance Army,

Uganda,

Add a tag

Eve Donegan, Sales and Marketing Assistant

Gérard Prunier is a widely acclaimed journalist as well as the Director of the French Centre for  Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. He has published over 120 articles and five books, including The Rwanda Crisis and Darfur. His most recent book, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe focuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. In this original post, Prunier discusses the history of the Joseph Kony led Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the ongoing conflict that led to almost 200 deaths this Christmas.

Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. He has published over 120 articles and five books, including The Rwanda Crisis and Darfur. His most recent book, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe focuses on Congo, the Rwandan genocide, and events that led to the death of some four million people. In this original post, Prunier discusses the history of the Joseph Kony led Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the ongoing conflict that led to almost 200 deaths this Christmas.

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) had its own way of celebrating Christmas: on December 25th it hacked an estimated 189 people to pieces in the Congolese town of Faradje, 80 km from the Sudanese border.

This homicidal explosion was a direct result of the combined attack by Congolese, Southern Sudanese, and Ugandan troops on the LRA stronghold in Garamba National Park in the DRC where the political-religious sect had been holed up for the past two years.

The LRA is made up of a semi-deranged leadership manipulating abducted illiterate children who have been brainwashed into committing atrocities. Indeed, its leader Joseph Kony has time and time again reneged on promises of turning up in Juba for peace talks with the Ugandan government, but the LRA’s murderous actions put it beyond the pale of civilized society. Beyond this moral judgment it remains for the social analyst to explain – not excuse – what is going on.

• Atrocious as it is, the LRA is the expression of the 23 year old alienation of the populations of Northern Uganda who have been punished beyond reason for the atrocities that they themselves visited upon the Southerners during the period of the Obote II and Okello governments (1980-1986). In spite of being preyed upon by the LRA vultures, the Northern Ugandan Acholi tribe still half supports it because it fights the Museveni regime.

• During its long history of fighting the Kampala government, the LRA has been aided and abetted by the Sudanese regime in Khartoum; not because it is Islamic (Kony’s confused “religion” is a hazy blend of Christianity, traditional cults, and messianic inventions), but because its is both a thorn in the side of Uganda and a problem for the potentially secessionist semi-autonomous government of Southern Sudan. Khartoum’s regime loves to mess things up towards the Great Lakes which it sees as an area of Islam’s future expansion.

• If we broaden our view even more, we can say that unfortunately the International Criminal Court which has indicted Kony and his officers for crimes against humanity (of which they are fully guilty) has cut off any avenue of negotiation with the cult leader who now prefers to die fighting than to end his days in prison in Europe.

• And last but not least, the LRA has acted as an evil magnet for all the social flotsam and jetsam resulting from years of war and insurgency in the whole region, from the Congo to Northern Uganda and from Southern Sudan to the Central African Republic. The LRA traffics in prohibited game animals, exploits various mines, and it gets money and weapons from Khartoum. Worse, it gives “employment” to disenfranchised young men (and even the girls it uses as servants and sex objects) who are left to fall through the supposed “safety net” of their inefficient governments and of a bewildered and slow-moving “international community.”

The tragic dimension of the LRA saga is a direct expression of the situation in Central Africa where neither guns nor diplomatic action seem to get anywhere. Given Kony’s messianic bend the best solution might be an exorcist.

I guess this might be considered 'old news' but I bought "Flow" the beginning of the year on the annual Paul Rodebaugh Book Hunt. Paul was a historian, retired history teacher, history guide, Quaker and a mad book collector who passed away about 10 years ago. He taught me to just 'buy it and read it when you get a chance' so I did!

I read mostly non-fiction and love history. Rivers are an interest and I have collected the complete 'Rivers of America' series and have read some of them. Since I live near the Schuylkill, go back and forth over it, love the history associated with it and other rivers, I was intrigued to have the river talk to me in first person!

It took me a few pages to get into it but once I did, I just couldn't put it down! You gave it a life: the boats and the canal, the crews, the waterworks and the horrible condition as it got into the 20th century. Why am I telling you; you know it as you lived and wrote about the river!

What a delightful read! I read it twice just to make sure I didn't miss what the river said! Now I have even more goodies to look at as the bibliography showed me a few items I had already read(Nolan, WPA American Guide on Phila)but now I have more!

My daughter is an elementary school librarian. I'll have to see if she has read any of your books!