new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: what a girl wants, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 23 of 23

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: what a girl wants in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

© Loree Griffin Burns

Colleen Mondor has put up a new post in her "What A Girl Wants" series, and it is a Must Read. The question this month is simple: what books of nonfiction do you wish your seventeen-year-old self could have read? There are some new women nonfiction writers on the panel (Tanya Lee Stone! Pamela S. Turner!) and you should

check out what they and the other panelists have to say on the topic. Have a pad and pencil handy.

(And when you do, you'll know why I have decorated this post with that gnarly beetle up there.)

The question this go-round was very simple - what novel (or novels) do you wish you had read the summer before your senior year in high school? (Consider this post a letter to your teenage self.) This is a question that hit very close to home for me. I spent that last high school summer working a couple of jobs and hitting the beach as much as possible. I read a lot of books, few of which I can remember now. My favorites were the same ones I had loved for years: Little Women and A Wrinkle in Time. Unfortunately, as I was not living through the Civil War nor seeking my lost father on the planet Camazotz, neither book was necessarily helpful to me. I loved them but as far as providing guidance on planning the coming years, they were sorely lacking.

The question this go-round was very simple - what novel (or novels) do you wish you had read the summer before your senior year in high school? (Consider this post a letter to your teenage self.) This is a question that hit very close to home for me. I spent that last high school summer working a couple of jobs and hitting the beach as much as possible. I read a lot of books, few of which I can remember now. My favorites were the same ones I had loved for years: Little Women and A Wrinkle in Time. Unfortunately, as I was not living through the Civil War nor seeking my lost father on the planet Camazotz, neither book was necessarily helpful to me. I loved them but as far as providing guidance on planning the coming years, they were sorely lacking.

There are many books I wish I had been able to read that summer including Pamela Dean's wonderful collegiate fantasy, Tam Lin (a title I still return to every year). Mostly though, I wish Sara Ryan's amazing Empress of the World was available in July 1985. For so many reasons I love this book but most particularly it is the way Sara shows teenagers working things out on their own - falling in and out of love, making friends, making academic choices and most importantly, viewing their parents with eyes both shrewd and wise - that makes me wish it was there for me as I was turning 17. Empress is a book about four teens finding their ways in the world and realizing that those individual paths are theirs to choose, regardless of the actions and expectations of others. The road might be tough and involve some bruising to the heart but it is still their road to choose.

That's what I needed help with back then - owning the choice of my future.

Sara wrote a sequel to Empress, The Rules for Hearts, which is also quite lovely and two companion mini comic books, Click and Me and Edith Head. I have copies of both the comics and love them but Me and Edith Head - well, that one is really special. Set before Empress this is all about the flamboyant character Katrina and how she learned to tap her inner fashionista and emulate the abundant creativity of Oscar winning costume designer, Edith Head. Seeing your parents as someone separate from yourself is a key element to Katrina's story. It is again about making your own choices and seeing where they take you. These are not stories about being wild or foolish (although there is a little bit of that, of course,) but rather being wild and brave and smart. Mostly though, Sara writes about being who you are. That last summer I didn't know how to figure that out and I think her characters would have helped me; they would have saved me many years of frustration until I finally got brave enough on my own.

Sara wrote a sequel to Empress, The Rules for Hearts, which is also quite lovely and two companion mini comic books, Click and Me and Edith Head. I have copies of both the comics and love them but Me and Edith Head - well, that one is really special. Set before Empress this is all about the flamboyant character Katrina and how she learned to tap her inner fashionista and emulate the abundant creativity of Oscar winning costume designer, Edith Head. Seeing your parents as someone separate from yourself is a key element to Katrina's story. It is again about making your own choices and seeing where they take you. These are not stories about being wild or foolish (although there is a little bit of that, of course,) but rather being wild and brave and smart. Mostly though, Sara writes about being who you are. That last summer I didn't know how to figure that out and I think her characters would have helped me; they would have saved me many years of frustration until I finally got brave enough on my own.

Here then are the books the group wish they had read back when they were about enter the wide wide world:

Beth Kephart: "Dear Beth, The world doesn't conform to your own ideas about it. It leaks. It scrambles out toward unseen possibilities, and between the cracks, beauty lies. Read Michael Ondaatje. Read Coming Through Slaughter, his pastiche of a book about Buddy Bolden and New Orleans and crimes of the heart.

Beth Kephart: "Dear Beth, The world doesn't conform to your own ideas about it. It leaks. It scrambles out toward unseen possibilities, and between the cracks, beauty lies. Read Michael Ondaatje. Read Coming Through Slaughter, his pastiche of a book about Buddy Bolden and New Orleans and crimes of the heart.

In honor of the Winter Olympics (which were truly fabulous) and female athletes everywhere, I've been thinking a lot about teen girls in sports. This of course has led me to thoughts of sporty female protags in books and the enormous lack thereof. So I asked the panel to give a thought to literary girls and sports. This ended up being a tough one for many as they responded that they were not athletes and so had never thought about this. I hope that after seeing the books that those who did respond came up with that they will rethink their initial reticence. I think the point is that you don't need to be an athlete to love a book about athletic girls - just as I didn't need to be a downhill skier to love Julia Mancuso. Sports are just another way to be excited about being a girl and honestly the more ways we can encourage that, the better.

So the questions: What books can you think of about famous female athletes in history? Do we honor them on the same level as male athletes? And what about game playing girls in MG & YA novels? Can you think of some great ones and do familiar teen girl tropes (like mean girls and romance) play into those novels? In other words, is a book about boys playing ball crafted the same as one about girls playing ball? Is the sport enough when selling a book about girl athletes?

Jenny Davidson: "I don't know that I'm widely read enough in this field to give a very good answer, but I've approached the question of girls' books about sport with new interest in the past couple years as I have become increasingly obsessed with triathlon. I don't think there's a clear equivalent of, say Chris Crutcher's books if we are thinking about very popular young-adult books and wanting ones that feature female rather than male athletes. I suspect that there aren't a ton of great sport biographies for teenage readers seeking books about athletes of either (any!) sex, since a would-be biographer would almost certainly be wiser to write the book for an adult market and hope that it found its way into the hands of suitable teenagers. (Michael Silver's biography of Natalie Coughlin, for instance, would be highly interesting and enjoyable to a teenager with an interest in swimming or collegiate sport more generally.)

Jenny Davidson: "I don't know that I'm widely read enough in this field to give a very good answer, but I've approached the question of girls' books about sport with new interest in the past couple years as I have become increasingly obsessed with triathlon. I don't think there's a clear equivalent of, say Chris Crutcher's books if we are thinking about very popular young-adult books and wanting ones that feature female rather than male athletes. I suspect that there aren't a ton of great sport biographies for teenage readers seeking books about athletes of either (any!) sex, since a would-be biographer would almost certainly be wiser to write the book for an adult market and hope that it found its way into the hands of suitable teenagers. (Michael Silver's biography of Natalie Coughlin, for instance, would be highly interesting and enjoyable to a teenager with an interest in swimming or collegiate sport more generally.)

A favorite book of mine of recent years that would fit the criteria you describe, Colleen, is Catherine Gilbert Murdock's novels DAIRY QUEEN and THE OFF SEASON. An older book, about a swimmer, is Tessa Duder's IN LANE THREE, ALEX ARCHER. We think of Noel Streatfeild's series (which I grew up rereading obsessively) as being mostly about children who aspire to work professionally as dancers or actors, but she also wrote several ones about girls pursuing sports such as WHITE BOOTS and TENNIS SHOES. And then, of course, there are the copious books about girls who are serious about horse-riding...

In short, I guess if I have an 'answer' to this question, it's that there is lots of good stuff out there, but perhaps it's not collected under a single rubric - as I often want to say, it's children's librarians who can do the best work here, reading w

No, I did not skip out on the conversation because it had to do with sex. I skipped out on the conversation so I could chase butterflies in Costa Rica. Honest. The panel went on without me, though, and shared their thoughts on books, sex, girls, and double standards. Check out the discussion at Chasing Ray.

Not sure what I am talking about? Read this introduction to the What A Girl Wants discussion series.

Passionate about girls and books? Check out the entire What A Girl Wants archive.

Looking for Costa Rica stories and pictures? Er, sorry. Not ready yet. Come back on Friday!?

Feminist Is Not A Dirty Word is the latest in the What A Girl Wants series by Colleen Mondor at Chasing Ray.

What A Girl Wants began in June 2009, and is a series of interviews with authors about the "current status of books for teen girls and what it says about both what they want to read and what publishers think they want to read." Topics since then have covered everything from mysteries to favorite books to recommendations to the most recent entry, about feminism.

I cannot believe I haven't linked to this series before! If you've been reading it, you know how great and in depth it is, with an amazing array of authors. If you haven't been reading it, start now! You'll feel as if Colleen invited all these women to her house, and you're invited, also, and now you're sitting around drinking wine, eating good cheese, and talking about bookish things.

Amazon Affiliate. If you click from here to Amazon and buy something, I receive a percentage of the purchase price.

© Elizabeth Burns of A Chair, A Fireplace & A Tea Cozy

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 2/3/2010

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Lorie Ann Grover,

Laurel Snyder,

Colleen Mondor,

Loree Griffin Burns,

Zetta Elliott,

what a girl wants,

Elaine Showalter,

Margo Raab,

A Jury of Her Peers,

Anne Bradstreet,

Add a tag

For the 11th question of her What a Girl Wants series, Colleen Mondor asked a number of us one of her typically challenging questions: What does it mean to be a 21st century feminist, and on the literary front, what books/authors would you recommend to today's teens who want to take girl power to the next level?

For the 11th question of her What a Girl Wants series, Colleen Mondor asked a number of us one of her typically challenging questions: What does it mean to be a 21st century feminist, and on the literary front, what books/authors would you recommend to today's teens who want to take girl power to the next level?

Lorie Ann Grover, Laurel Snyder, Loree Griffin Burns, Margo Raab, and Zetta Elliott all came through with reliably interesting responses. I was caught up in a series of corporate projects and could not respond in time.

Today, however, I'd like to put my two cents in by recommending Elaine Showalter's A Jury of Her Peers: Celebrating American Women Writers from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx to readers of any age, gender, or race who wish to understand and celebrate just how hard women have had to work to put their voices on the page—and how women's voices have and will continue to shape us.

Anne Bradstreet, one of this nation's first women writers, entered print, in Showalter's words, "shielded by the authorization, legitimization, and testimony of men." In other words, Showalter continues, "John Woodbridge, her brother-in-law, stood guarantee that Bradstreet herself had written the poems, that she had not initiated their publication, and that she had neglected no housekeeping chore in their making."

No vanity allowed, in other words, and no leaving those dishes in the sink.

Showalter's book—which yields insight into the stories of Phillis Wheatley, Julia Ward Howe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Emily Dickinson, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Dorothy Parker, Zora Neale Hurston, Pearl Buck, Shirley Jackson, Harper Lee, Sylvia Plath, S.E. Hinton, Grace Paley, Joan Didion, Lorrie Moore, Jayne Anne Phillips, Sandra Cixneros, Amy Tan, Louis Erdrich, Jhumpa Lahiri, Gish Jen, and so many others—is itself a piece of history, for it is, unbelievably, the first literary history of American women writers.

Showalter suggests that the development of women's writing might be classified into four phases: feminine, feminist, female, and free. Anyone who wants to know just how we got to free (and to ponder, with the evidence, whether or not we're really there) should be reading this book.

In late December I read an article in the Washington Post about Geraldine Ferraro's extreme disappointment over the young women who voted for Obama rather than Hillary Clinton. Her point was that all other things being equal (meaning you were going to vote Democrat anyway) then women should have put Clinton over the top as women should have felt the higher need to place a woman in the Presidency. Here's a bit:

In late December I read an article in the Washington Post about Geraldine Ferraro's extreme disappointment over the young women who voted for Obama rather than Hillary Clinton. Her point was that all other things being equal (meaning you were going to vote Democrat anyway) then women should have put Clinton over the top as women should have felt the higher need to place a woman in the Presidency. Here's a bit:

Ferraro was livid, and distraught. What more did Hillary Clinton have to do to prove herself? How could anyone -- least of all Ferraro's own daughter -- fail to grasp the historic significance of electing a woman president, in probably the only chance the country would have to do so for years to come? Ferraro hung up enraged, not so much at her daughter but at the world. Clinton was being unfairly cast aside, and, along with her, the dreams of a generation and a movement.

What intrigued me about this piece was the notion that feminism means you inherently must support the best qualified woman, over the equally qualified man - at all times. So if I voted for Obama and not Clinton, I am not as "good a feminist" as I should be. This also made me wonder just what being a feminist means in the 21st century and beyond that, if teens today have any idea what feminism used to mean and why it continues to matter. Is feminism an outdated word today? Is it even a negative word? And yet Lily Ledbetter proved that inequalities exist and must be rectified and who can argue with her situation - demanding equal pay for equal work regardless of gender? But do today's teens see gender bias - and should they?

Basically, the question is, what does it mean to be a 21st century feminist and on the literary front, what books/authors would you recommend to today's teens who want to take girl power to the next level?

Lorie Ann Grover: "No way, should a girl vote for a woman just because she's a woman, Colleen! Both my girls would be upset to hear that they were expected to do so. Thankfully, they are not of my mother's world, but their own. They have the luxury of looking at issues over gender representation. That said, a hip young feminist blog is The F Bomb . This was recommended by iheartdaily, and it's a great, fresh voice for teen girls.

Lorie Ann Grover: "No way, should a girl vote for a woman just because she's a woman, Colleen! Both my girls would be upset to hear that they were expected to do so. Thankfully, they are not of my mother's world, but their own. They have the luxury of looking at issues over gender representation. That said, a hip young feminist blog is The F Bomb . This was recommended by iheartdaily, and it's a great, fresh voice for teen girls.

Girldrive by Nona Willis Aronowitz and Emma Bee Bernstein is compelling, both the book and blog. Here two young women hit the road and interview women across the country about feminism. Answers are different, current, and colorful.

Those two sources come immediately to mind. Other than that, I think reading broadly through YA lit will bring a great balance. The books of today empower girls to think for themselves and stride forward."

(ETA: Read a NY Magazine Q&A with Nona Aronowitz.)

Laurel Snyder: "What I cannot stop thinking about, as I ponder this question, is that no matter how much things change, teenage girls are still boy-crazy. For healthy natural reasons, of course, but this reality

Laurel Snyder: "What I cannot stop thinking about, as I ponder this question, is that no matter how much things change, teenage girls are still boy-crazy. For healthy natural reasons, of course, but this reality

Finally, here is part 3 of our December feature on books recommended for teen girls. Be sure to check out Part 1 and Part 2 and please - PLEASE - buy books for the girls in your life this holiday!

Lorie Ann Grover says: "When Colleen asked for a book recommend for What a Girl Wants, I went back and scrolled through my goodreads. What have I read this past year, that I'd want to place in the hands of a teen girl? There are so many books! Certainly every readergirlz main feature and postergirlz recommended read. But what rises to the top for me, personally? I've chosen three:

Lorie Ann Grover says: "When Colleen asked for a book recommend for What a Girl Wants, I went back and scrolled through my goodreads. What have I read this past year, that I'd want to place in the hands of a teen girl? There are so many books! Certainly every readergirlz main feature and postergirlz recommended read. But what rises to the top for me, personally? I've chosen three:

Justina Chen's North of Beautiful because every girl should be challenged to discover her own definition of beauty. Teen girls will identify with Terra as she charts her path away from her constraining, abusive father. They will cheer when she finds truth and beauty through art, and she gathers insight through her new friend Jacob. The beautifully crafted sentences and rounded characters will hold readers with hope and call them to find their own north of beautiful.

Laura Resau's Red Glass is my second recommend. With rich, beautiful language, readers will join Sophie on her journey into Mexico during a summer road trip. An eccentric cast, cultural diversity, and a hint of magical hope infuse this work which will expand the scope of teen girls today. Whether they be touched by the Bosnian war refuge or the six year old Mexican boy who has crossed the U.S. border illegally, the readers' experiences and empathy will be broadened.

And Beth Kephart's House of Dance is my third recommend. The lyrical beauty of Beth's prose just may incite teen readers to reach out to an older generation. As Rosie is charged with tending to her grandfather dying of cancer, she uncovers the life that he loved. Through ballroom dance instruction, Rosie's confidence blossoms until she can stand and give back herself. The sense of community and family love found in this gentle journey will resound in teen readers.

So there are three books of hope, I just realized. As I say to teen readers, "There's hope. Look." (Loose Threads, 2002)"

CM: Oh Justina Chen! Oh Beth Kephart! Can I say how much I love their books? Justina's Nothing but the Truth (and a few white lies) remains one of the funniest and most normal books I've read in ages. And yet it is anything but typical it's just that any reader can see themselves in Patty's frustrations. And Beth's Nothing But Ghosts is a revelation, plain and simple. Such gorgeous writing and such a light touch when it comes to family drama and romance and coming-of-age. A book to sink into!

Laurel Snyder says: "Ah, the randomly-chosen holiday gift book! I remember (seriously, folks) my dad giving me a copy of Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust for Hanukkah one year, no lie.

Laurel Snyder says: "Ah, the randomly-chosen holiday gift book! I remember (seriously, folks) my dad giving me a copy of Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust for Hanukkah one year, no lie.

And while that was kind of an intense experience, I'm going to argue for intensity today. I'm going to say that the

And just as we did last week, here are some more book recs for 12 & up girls from the fabulous What a Girl Wants crew:

Loree Griffin Burns suggests: "My WAGW holiday book picks are a collection of truly fantastic nonfiction that I read this year. The books themselves cross genres and reading levels but are united in their exploration of one amazing organism: the mighty redwood tree. I think it’s fascinating how the different authors explored this single topic, and teenaged girls with an interest in science, discovery, or writing will surely enjoy a jaunt through their pages.

Loree Griffin Burns suggests: "My WAGW holiday book picks are a collection of truly fantastic nonfiction that I read this year. The books themselves cross genres and reading levels but are united in their exploration of one amazing organism: the mighty redwood tree. I think it’s fascinating how the different authors explored this single topic, and teenaged girls with an interest in science, discovery, or writing will surely enjoy a jaunt through their pages.

REDWOODS, by Jason Chin is not exactly written for teenaged girls, but it will interest them anyway. Chin takes the idea of a redwood forest and builds it into a grand, visual adventure. This picture book was actually my first introduction to redwoods, and it inspired me to learn more. (I love when picture books do that!)

OPERATION REDWOOD, by S. Terrell French. This middle-grade novel tells the story of three kids who take the preservation of a certain stand of redwood trees very, very seriously. The math is perfect: Kids = Heroes.

EXTREME SCIENTISTS, by Donna M. Jackson. This middle-grade photo-essay explores three different scientists, one of whom is Steven Sillett, the first scientist to climb up into the redwood canopy and explore. How he gets up there is just as fascinating as what he finds when he gets there, and the stunning photographs make this book a great complement to the others on the list. (CM: I reviewed Extreme Scientists in my feature on nonfiction titles in the new issue of Bookslut. Loved it!)

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC magazine is one of my favorites, and a subscription starting with the October 2009 issue would make a perfect addition to a redwood-themed holiday gift basket, because it features a cover article on these super-trees … complete with a pullout poster that is crazy amazing.

The last redwood book on my list is the one that intrigued me most, and since it was published first, I suspect that it might just have inspired the other books on this list. THE WILD TREES, by Richard Preston is creative non-fiction at its very best: intensely readable and full of information that is so interesting you wonder after reading it why you hadn’t explored the topic before. The book was primarily marketed to adults, but I think it will be equally interesting to teenagers; who can resist a book that inspires, motivates, saddens, and scares one witless all at the same time? [Parents will probably want to know there is a love scene in the book. And, yes, it takes place in the redwood canopy!]

CM: This is an inspired subject and some excellent choices for sure. For readers looking for other woodsy type stories I highly recommend The Wild Girls by Pat Murphy about two girls who meet in the woods, become frien

CM: This is an inspired subject and some excellent choices for sure. For readers looking for other woodsy type stories I highly recommend The Wild Girls by Pat Murphy about two girls who meet in the woods, become frien

We're taking a break from the heavy subjects this month with the What A Girl Wants series and instead offering up the group's collective wisdom when it comes to books and girls. Although we are mostly aimed at the 12 & up crowd, you will find in this post (and Part 2 next week) lots of ideas for what we think you should buy for the girls in your life. I've mostly left the choosing to the WAGW crew although, well, I do chime in with some additional ideas based on their suggestions. Happy shopping - and more than anything, happy reading!!!

Jacqueline Kelly suggests: "The Diary of Anne Frank. This should be compulsory reading for every girl. And for every boy. And every adult, for that matter. This haunting book will stay with you for the rest of your life."

Jacqueline Kelly suggests: "The Diary of Anne Frank. This should be compulsory reading for every girl. And for every boy. And every adult, for that matter. This haunting book will stay with you for the rest of your life."

CM - As it happens, there are two new looks at the diary out this year: Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, the Afterlife by Francine Prose wherein the author suggests that Anne revised her diary and planned to publish it after the war and Anne Frank: Her Life in Words and Pictures by Menno Metselaar, a visual guide to her life published this fall by Roaring Brook.

Melissa Wyatt suggests: "For girls who are looking for more supernatural romance, I highly recommend THE CHINA GARDEN by Liz Berry. A strong female protagonist who finds her own way to accept a seemingly inescapable destiny, a real live human boy for her to love, an intricate and beautiful mystery based in British folklore and enough steam to set off plenty of palpitations.

Melissa Wyatt suggests: "For girls who are looking for more supernatural romance, I highly recommend THE CHINA GARDEN by Liz Berry. A strong female protagonist who finds her own way to accept a seemingly inescapable destiny, a real live human boy for her to love, an intricate and beautiful mystery based in British folklore and enough steam to set off plenty of palpitations.

And this is the perfect time to catch your girl up on Megan Whalen Turner's magnificent Thief series. The fourth book, A CONSPIRACY OF KINGS, will hit bookshelves in March. (And psst! It's fantastic!) So gear up with the first three books: THE THIEF, THE QUEEN OF ATTOLIA and THE KING OF ATTOLIA. Set in a psuedo-Mediterranean/medieval world and full of political intrigue and complex relationships, these books are somewhat demanding, but will reward the sophisticated reader many times over. Give these books to fans of Diana Wynne Jones."

CM - If you are a fan of Turner's and have yet to discover Diana Wynne Jones then can I strongly - STRONGLY - suggest you get yourself right over to her end of the shelves and start ordering? My favorite of hers is Fire & Hemlock, a retelling of the Tam Lin ballad which is sadly out of print (why oh why??) but if you find it in a used store then give it to a teen you know asap. Or you could buy Pamela Dean's amazing version of Tam Lin set on a college campus in the early 1970s which I also adore.

Zetta Elliott suggests: "One of the most compelling books I’ve read recently was Marcelo in the Real World by Francisco X. Stork. Jasmine and Marcelo (who has Asperger’s syndrome) forge an intimat

Zetta Elliott suggests: "One of the most compelling books I’ve read recently was Marcelo in the Real World by Francisco X. Stork. Jasmine and Marcelo (who has Asperger’s syndrome) forge an intimat

Another installment in Colleen Mondor's

"What A Girl Wants" series is posted over at Chasing Ray. This time we are discussing socioeconomics in teen literature.

Check it out.

In question number seven of her fantastic series, What a Girl Wants, Colleen Mondor asked us to reflect on whether historic MG and YA fiction addresses socioeconomic status more effectively than contemporary titles, and whether or not readers need to read about people who are experiencing their same financial struggles, or prefer to live vicariously inside socioeconomic fantasies. As always, I had to think long and hard about this one. Check out what Jenny Davidison, Zetta Elliott, Melissa Wyatt, Laurel Snyder, Sara Ryan, Loree Griffin Burns, Kekla Magoon, Mayra Lazara Dole, and I had to say about the topic. As always, I wish that I could be in a room with these bright lights, talking the issue out.

In question number seven of her fantastic series, What a Girl Wants, Colleen Mondor asked us to reflect on whether historic MG and YA fiction addresses socioeconomic status more effectively than contemporary titles, and whether or not readers need to read about people who are experiencing their same financial struggles, or prefer to live vicariously inside socioeconomic fantasies. As always, I had to think long and hard about this one. Check out what Jenny Davidison, Zetta Elliott, Melissa Wyatt, Laurel Snyder, Sara Ryan, Loree Griffin Burns, Kekla Magoon, Mayra Lazara Dole, and I had to say about the topic. As always, I wish that I could be in a room with these bright lights, talking the issue out.

© Kelly Connors

I know, I know…. I am supposed to be away from my computer all month. But the truth is that I am working a teeny bit, in between summer adventures, and part of that work this week is participating in another ‘What A Girl Wants’ discussion over at Colleen Mondor’s Chasing Ray blog. This week we’re discussing non-fiction, and I’m officially inviting ALL of you to join the discussion. So, if you are so inclined, head on

over, hear what the WAGW panel has to say about nonfiction for teen girls, and let us know what you think about the topic. What great YA nonfiction have you read lately? What inspirational women* would you like to read about? Who and what did you read about when

you were a teen? Come on over and have your say.

*Eleanor Roosevelt, whose statue from the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington DC is pictured above, inspires me constantly. I re-read parts of Russell Freedman’s ELEANOR ROOSEVELT: A LIFE OF DISCOVERY while writing up my WAGW response, and I was inspired all over again. Amazing woman, amazing biography.

** I submitted my WAGW response very late, so if you've already visited the discussion (ahem, Jeannine), then consider a second trip!

This week's entry stems largely from my acute frustration after reading Tanya Lee Stone's Almost Astronauts. The book is fantastic - really really well done - and I can't recommend it enough (It will be formally reviewed in my September column which is all things Moon Landing). What bothered me is that I was raised on the Space Coast of Florida and watched rockets launch from my front yard and yet I had never heard of the women in the Mercury 13 - not once. They never showed up in college either, when I studied Aviation (including Aviation history and they were all killer pilots) or when I studied history (which included the Gemini, Mercury and Apollo programs). It's not that I would have decided to be an astronaut if only I had known about them, but rather that I had no clue that women did this then - before I was born. So I got to looking at nonfiction in general for teens, especially books written about real women and real girls and real subjects that would interest teenage girls who, like teenage boys, generally have no idea what to do with their lives, and what I found was monumentally disheartening. Lots of mythic history (hello Betsy Ross and Molly Pitcher), lots of dead history (poor Amelia Earhart and Marie Curie), lots of commonly known and celebrated but not likely to be repeated history (go Rosa Parks!) but books about women scientists and anthropologists and pilots (who didn't disappear) and marine biologists and artists and writers and museum curators and horse trainers and volcanologists and on and on and on?

This week's entry stems largely from my acute frustration after reading Tanya Lee Stone's Almost Astronauts. The book is fantastic - really really well done - and I can't recommend it enough (It will be formally reviewed in my September column which is all things Moon Landing). What bothered me is that I was raised on the Space Coast of Florida and watched rockets launch from my front yard and yet I had never heard of the women in the Mercury 13 - not once. They never showed up in college either, when I studied Aviation (including Aviation history and they were all killer pilots) or when I studied history (which included the Gemini, Mercury and Apollo programs). It's not that I would have decided to be an astronaut if only I had known about them, but rather that I had no clue that women did this then - before I was born. So I got to looking at nonfiction in general for teens, especially books written about real women and real girls and real subjects that would interest teenage girls who, like teenage boys, generally have no idea what to do with their lives, and what I found was monumentally disheartening. Lots of mythic history (hello Betsy Ross and Molly Pitcher), lots of dead history (poor Amelia Earhart and Marie Curie), lots of commonly known and celebrated but not likely to be repeated history (go Rosa Parks!) but books about women scientists and anthropologists and pilots (who didn't disappear) and marine biologists and artists and writers and museum curators and horse trainers and volcanologists and on and on and on?

Not so much. I should clarify that I'm looking for something more than the short standard biographies and NF titles provided in series for middle grade readers. What I'm looking for is something that dwells between child and adult (as teenagers do) and also offers insight into how ground breaking and amazing women traveled their paths from girlhood to woman. That's what I haven't seen so much of and what I long to discover.

So here is a discussion that has, surprisingly, proven to be the toughest for our panel. The question: How about the real girls? We all know that teen nonfiction is not a popular genre for publishers. The assumption seems to be that teens can jump right into adult NF for information they might need for reports, etc. To me though the adult titles are often densely written and more importantly do not address subjects teens would be interested in - or don't present them in a manner that would be more appealing to teens (more pictures, etc.) What subjects do you think should be addressed in YA NF that teen girls would want to read about and just as important - should read about? Who are the real girls and real issues we are missing and how would learning about them help the girls of today?

Beth Kephart: "I have had the great privilege of spending a lot of time with teens not just my own son, but young aspiring writers, the kids from church, the crowd of adventurous souls with whom I traveled to Juarez, and also, in that virtual way that all of us here understand, the younger bloggers who daily teach me so much. These kids are smart. These kids are outrageous in what they already know, in what they already reach for, in what borders and barriers they already cross.

They yearn, it seems to me, for place. They yearn to know more about worlds that are not theirs, about people they've not met. The anthropological. The sociological. The tribal. The vanishing. I'm not talking about guidebooks. I'm not talking about textbooks. I'm talking about books that respectfully, intelligently, seductively open worlds to teens.

Zetta Elliott: "While visiting my mother last month, I opened a drawer in my old desk and found a high school report I’d written on Wuthering Heights—on the front cover was a lovely image of Brontë, which I distinctly remembered cutting out of the musty encyclopedias we kept in the basement! As a professor, I began instructing my students not to use secondary sources because plagiarism was an issue, and I felt it was important for them to develop their own ideas and analyses instead of relying on theories developed by others. It can be hard for young people to develop their own voice and/or opinion when they’re told over and over that they lack the experience and/or expertise to come to their own conclusions. I’d like to see more nonfiction for teens that incorporates source material, like Tonya Bolden’s Maritcha: A Nineteenth-Century American Girl. I also believe nonfiction writers need to meet teens where they are—and that means incorporating lots of audio and visual content. I begin most of my classes with music because it’s appealing, accessible, and presents text (lyrics) in a different way. We study television commercials, films, essays, fiction, poetry…there are so many ways to approach a given topic. Teens need to understand that history is a story anyone can tell, so long as you substantiate your claims. "

Laurel Snyder: "Ooh! Ooh! Well, it seems to me that part of the problem with nonfiction is that teens are already being crammed full of "information" at school. So, even if you write a good biography of, say, Abigail Adams, who was an amazing woman, I can't help thinking it'll be met with groans of "Mooooore schoolwork?" Same with anyone likely to appear on an AP history test.

BUT! As an author, I wish all the time that I had the resources to research and write nonfiction that's off the beaten track. Biographies and histories of things that never make it into textbooks. I wrote a story for BUST a few years back, about the women of the carnival freakshows. Written well, a book about such women (or just one) would be a chronicle of an age, as it would touch on how/why these women found their way to the carnie world. Many were immigrants, or women of color. Many had disabilities. Some lived in partnerships with other women.

Likewise the dance world (I'd die to write about Anna Pavlova), the theater world, etc. Incarcerated women. I read a CRAZY biography of Tallulah Bankhead last year! WOW! I think dramatic stories like that, from outside the mainstream, would provide an alluring window on history.

Maybe I'll get around to it, once my kids are a little older and I can travel and do the research."

Lorie Ann Grover: "I do believe teens can access adult nonfiction without hesitation, Colleen. So, this hasn't been a concern for me, currently. However, with two teen girls in my house, I can say that when the perfect topic crosses their path in a YA format, that book is well-loved. A perfect example is Deborah Reber and Lisa Fyfe's In Their Shoes: Extraordinary Women Describe Their Amazing Careers. The work is toted about, read again and again, and shared with friends. The nonfiction is accessible and pertinent. In the same vein is The Great Jobs series by Blythe Camenson. Particularly in our house, Great Jobs for Geology Majors and Great Jobs for Anthropology Majors have been checked out repeatedly from the library.

Believing teens can access adult works, I ask myself what subjects are particular to teens that maybe could be explored more? How about: health for teens, more series on careers, dating and relationships, teen finances and savings, and goal setting as a teen. I'm thinking practical topics that are particularly relevant to the teenager.

I'd personally love to see a collection for teens about teen life around the world. Maybe that's a future endeavor for my cultural anthropology major...

Jenny Davidson: "I hear you on the need for accessible and interesting nonfiction books on issues that will be of interest to girls in particular - but isn't it possible that there just isn't a big enough market for it to make sense for publishers and writers to invest their resources this way? It is my strong opinion, as a reader and a writer, that a wonderfully well-written adult nonfiction book will be accessible to thirteen- or fourteen-year-olds who are fully fluent readers. What would be an example? Well, let's say Anne Fadiman: her book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down is in no sense a YA title, and yet I think it would be of considerable interest to many high school students. Popular science writing, at its best, also crosses over in this way - the essays of Oliver Sacks, for instance (or I think of books like Armand-Marie Leroi's Mutants or Jonathan Weiner's Time, Love, Memory as books that would also be very suitable for this age group). So that in this case it seems to me librarians are the ones who have the most to offer, in terms of helping steer kids to the real treasures that exist out there but that will not always be clearly designated for teens. Well-written biography in particular can offer girl readers some of the pleasures of a novel but with access to or insight into various fields of history or science or what have you - but I would think that it will make more sense for most biographers, especially if they are doing original research, to write for the adult market in the first place..."

Sara Ryan: "This is another question I can't answer without thinking about my own reading choices as a teen. Here are three nonfiction titles I remember:

1. Our Bodies, Ourselves. It was put into my hands by an older friend who'd intuited that I would soon benefit from some of the information inside. I would never have taken it off a library shelf, but in the safety of her apartment, it was okay to read. 2. Color Me Beautiful. I wish I didn't have such vivid recollections of this title, but I was fascinated by the premise that if you just knew what season you were, everything else in your life would fall into place. 3. Medieval People, by Eileen Edna Power. I was also fascinated by the Middle Ages, and I appreciated that the book was actually about people from the past, as opposed to Important Historical Events.

None of these titles were written for a teen audience, but they were all about subjects in which I had a compelling interest. If I were a teen today, I'd be looking online for equivalents of the first two, since despite my fascination, I found health information and fashion equally embarrassing to contemplate.

The problem I have when I try to think about teen-girl-specific nonfiction is that so many of the subjects that come to mind are exactly the kind of things I wouldn't have wanted to admit I was interested in. And if the topic was innocuous, as with Medieval People, I'd have found a "For Teens!" treatment condescending.

So maybe teen-girl-specific nonfiction is more for parents, librarians, teachers, and the rare but vital Other Trusted Adults to buy, and simply leave somewhere the girls might stumble across it.

Mayra Lazara Dole: "My main concern isn’t educated girls who read. Soon they’ll have a myriad of YA nonfiction titles written by white authors filled with white successful women. I vouch for popularizing Latina/all women of color scientists and athletes while dispelling female myths in order to inspire girls who don't read. It’s my perspective that we need to update/rewrite history texts to include all Latinas and women of color scientists, politicians, athletes, etc., and LGBTQl’s contribution throughout history. Our stereotypes about Latina/women of color, and LGBTQI's tells us who we are as people, play a role in all our decision-making, in who we choose to interact and befriend or shun, and, in how we advance in life and in our careers.

Rain can erode mountains and boulders. As authors, let’s be the rain…

A silly last thought: in order to inspire teens who don’t read to delve into books, I suggest we consider hyper-manipulating titles:

TEEN SEX! = How to prevent pregnancy and STD’s

GO GREEN & GET the GUY! = Encouraging teens to take care of their bodies and the environment.

READ THIS and DIE! = Nutrition, eating healthy foods so you avoid heart disease, etc.

LGBTQI’s RULE THE WORLD! = text depicting gay characters in history.

WHO ARE OUR FOUNDING MOTHERS = ?"

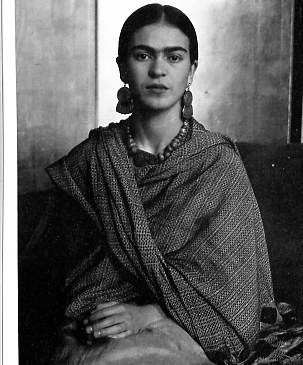

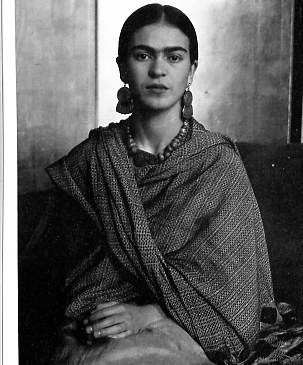

[Post pics: Artist Frida Kahlo in 1931, age 24; Maritcha Rémond Lyons, first Black graduate of Providence High School; Russian dancer Anna Pavlova in 1912; anthropologist Ruth Benedict; author Anne Fadiman; astronaut Eileen Collins - first female shuttle pilot and first female shuttle commander; Cuban singer Celia Cruz]

As many of you may recall, Margo Rabb wrote an article on being published YA in the NYT earlier this year that set off a bit of a firestorm about what it means to be a YA writer vs adult and if one or the other is better. This comes up again and again, if not from authors (although Colson Whitehead found himself in the middle of it just a few months ago after a casual remark) then from readers. There is a constant and continuous question over what is YA and if YA matters or should even exist as a separate genre. We aren't going to solve those questions here today but at the very least I did want to delve into just what subject areas might be more important for a teenage girl than an adult woman - in other words, if YA did not exist would teens still be getting the best reading experience?

As many of you may recall, Margo Rabb wrote an article on being published YA in the NYT earlier this year that set off a bit of a firestorm about what it means to be a YA writer vs adult and if one or the other is better. This comes up again and again, if not from authors (although Colson Whitehead found himself in the middle of it just a few months ago after a casual remark) then from readers. There is a constant and continuous question over what is YA and if YA matters or should even exist as a separate genre. We aren't going to solve those questions here today but at the very least I did want to delve into just what subject areas might be more important for a teenage girl than an adult woman - in other words, if YA did not exist would teens still be getting the best reading experience?

Before I post the question though, I wanted to point everyone in the direction of a new blogger: Young, Black, A Reader. "MIss Attitude" is a Black teen reviewing books with Black characters and after the last WAGW discussion I can't begin to stress how important it is to support this young woman in her endeavors. If you want to get a good taste of what she's trying to do - and how frustrated she is - then read her post on trying to find teen books with Black characters at the local B&N. It's a good blog and an important voice in the blogosphere, so let's send her some encouragement.

Now onto our discussion of just what sort of subjects do teen girls need to address in their reading that they can not simply find in adult titles. In other words, I asked the group why do we need YA titles for girls in particular and what those books could/should include.

Sara Ryan: I was struggling with my response in part because, much like the last question, I feel like I could write a dissertation and not think that I'd covered the topic adequately. So I asked a couple of writer friends why they thought we needed YA titles for girls. Both of their answers had to do with respect: respect for a group of people, teenage girls, who are not, as a rule, respected in contemporary American culture.

It's easy to look at pop culture and think that teen girls -- white, thin, straight, rich teen girls, to be precise -- are held up as some kind of an ideal. But there are, of course, a whole lot of teen girls who do not fit into those categories, and besides, girls -- not to mention adult women -- are only supposed to look like teenage girls, not act like them. How do you insult an adult? One way is to accuse them of acting like a teenager; especially a "bitchy teenage girl." You can denigrate a piece of art or music or literature by calling it adolescent. I don't want to turn this into Identity, Round Two, but I do think that part of why we need YA for girls is so that girls can read books that resonate with what they're experiencing -- or take them very far away from it, depending. The point Alyssa made in the Girl Detective comments is well taken: "As far as the serious/meaningful stuff goes, we teenagers live with the 'hell' of high school and all the moronic teenage angst in general. I've noticed that many adult authors of YA want to 'give us something to think about' and 'change our lives.' Those are the kind of books the teachers make us read in school. But the truth is, when we go shopping for a novel and spend our money, we just want to be swept away and entertained."

So one day you might want the Victorian-style magic, ass-kicking, and wit of the girls in Libba Bray's A Great And Terrible Beauty. Another day, you might want to read about a girl with a messed-up family, whose family is messed up maybe along different lines than yours, but still in a way you can recognize, like Deanna Lambert's in Sara Zarr's Story of a Girl. On yet another day, the matter-of-fact competence and scientific smarts of Dewey Kerrigan in Ellen Klages' Green Glass Sea and White Sands, Red Menace might appeal. Or the torturous crush on a teacher in Jillian and Mariko Tamaki's Skim. Or the hilarious Quinceañera for the Gringo Dummy in Nancy Osa's Cuba 15.

Another reason we need YA for girls is that it can be a way into subjects you might not otherwise encounter -- or admit to yourself you want to know about. I've heard from many girls for whom Empress of the World is the first book they've read that features girls in love with each other. This is, of course, an aspect of YA that causes controversy, since many adults seem unable to understand that you don't necessarily read fiction as a how-to manual. (Otherwise, judging from the popularity of mysteries among adults, the homicide rate would be considerably higher.)

And there's something about voice in the mix, too. I think the YA authors who nail teen girls' voices credibly -- and part of that is recognizing that a monolithic Teen Girl Voice does not exist -- respect girls and their lives in a way that authors of adult books with teen girl characters often don't. The YA authors who get it don't treat being a teenage girl as the best or worst time ever, or -- as is perhaps most common with authors of adult books -- as a time of such excruciating awkwardness that they can barely stand to evoke it. Instead, the authors who get it present girls' teen years simply as a time when a lot is happening, some of it confusing, some of it exhilarating, some of it tragic, some of it amazing. Much like, you know, the rest of life.

Zetta Elliott: I’m new to the field of YA lit so I can’t claim to be an expert, and I don’t remember spending much time on “teen lit” when I was a teenager myself. I recall stealing my older sister’s teen romance novels when I was a pre-teen, but that had more to do with wanting to seem grown. I vividly remember reading Mildred D. Taylor’s novels more than once, and despite the protagonists' young age, the subject matter struck me as very adult; it was my introduction to life in the Jim Crow South, and was probably the start of my lasting interest in the US history of racial violence. I wasn’t learning that history in my suburban Toronto high school, so I suppose I’d say that YA lit should make accessible those topics made “unmentionable” by (well-intending?) adults. When I teach my course on lynching, my college students are often outraged that such vital history wasn’t covered in their school curriculum. But what’s the “right” age to learn about lynching? I’ve written a picture book story that touches on mob violence but no publisher has expressed interest, despite the success of Bird, which also deals with “sensitive” issues. I think any subject can be made comprehensible to young readers without being gratuitously explicit or traumatic, but you’d need to find a press with the courage to take on potential controversy.

The more YA lit I read, the more I’m struck by the split: novels that are about teens versus novels that are marketed to teens. The latter are often marked by “lite” writing and silly gimmicks that aim to make the novel seem experimental or innovative in terms of form. But real daring resides in the writing itself, and I think teens deserve novels on every topic, told from as many different points of view as possible. Books that offer narrative possibility (instead of filling in all the blanks) open the door for continued conversation, so I’d also say that we need adults who have the courage to face the daunting questions that teens need to ask.

Laurel Snyder: Okay, deep breath.

In some ways, this is the part of YA I have trouble with as a writer. It's part of why I don't really write YA (I write MG), why I steer clear of "issues" in my books. Because I haven't figured out how to do it right yet. I don't know how to find a balance, a light touch. I'll be interested to hear what the others have to say.

I worry about writing "about." I would, of course, like to think that young women would find any issues they faced in the literature we provide. That our books would be of use to them as they grow. But what makes a good resource doesn't always make a good book. Right? It's the very process of writing "about" something like cutting or rape or food issues that can get in the way of the story or the language. The sensitivity we bring to bear when we write for the young, the sense of ourselves as educators or mentors or good examples... can turn literature into propaganda. It feels like there's never the option of a tragedy. Like there's no room for nihilism when we're trying to deliver a hopeful message. And that feels limiting to me. I'm intimidated that.

I read Wintergirls this spring, and it KNOCKED MY SOCKS OFF. Because it felt so true. I danced as a teen, and struggled some with food and body image. And the fact that the books explores the death of such a girl, and the near-death of another, in such a poetic, real, painful way, shocked and awed me. I want to think I can write like that, but I'm not sure. And there's so much at stake in such a book, I'm scared to fail.

Whew.

Beth Kephart: We are perpetually in the process of becoming ourselves; when we are teens the yearning, the needing, the bending and unbending is all the more intense. We turn, then, to books that make us feel less alone, that articulate or validate our choices, that embrace our apparent differentness, that show us a way, that make it clear that there is not only one way, that yield, to us, context. I think we also turn to books that help us understand how stories work, that help us find the narrative in our own lives.

Is To Kill a Mockingbird a YA book? Is the Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time? I don't, in fact, care how they are labeled; they are books that are essential for teens. Beautifully written, searingly arranged, brilliantly instructive without for a second being didactic, they set down a path for younger readers - they broach the big issues, subjects, themes of identity, prejudice, toleration, and compassion. Can such things be found in adult titles? Of course they can. But books like these open doors to such issues; they open themselves freely to the hearts of younger yearners.

Lorie Ann Grover: I believe teen girls need stories that express their own voices and introduce them to new ones that speak outside of their worldviews. Any topic can potentially engage a teen if it's contained in a meaningful story. The teen protagonist is merely a conduit which connects the reader, with a shorter life experience, to the writer.

So, what can be found in the teen novel not found in an adult work? Nothing, aside from a guarantee of hope in some measure, even if it's small. At least today, I still find this to be true. Otherwise, there will be the same literary merit, engaging plot, and credible characters. There will be the same value.

At ALA, Libba Bray was recently telling me about her book tour in Germany where she found YA and adult works esteemed equally. I am hopeful we might reach this conclusion in the states. Let writers craft their stories and people from all walks find the words, regardless of age or place in life.

Jackie Kelly: Since I'm apparently the geezer in the group, I'm going to tell you all the things I couldn't read about as a young adult simply because they were not written about in any books. At all. Divorce, adultery, sex, pre-marital sex, sex of any kind, and I'm not kidding. Drug abuse, alcohol abuse, marijuana. Anorexia, bulimia, dieting, laxatives. Birth control, abortion, STD's. Periods, tampons, pads. Homosexuality, lesbianism, bisexuality, transvestism, transgenderism. Masturbation, puberty, body changes. Again, no kidding. Depression, anxiety, suicidality. Beer drinking, pills (although characters who smoked cigarettes were A-okay). Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse. Shop-lifting, cheating, broken friendships. Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists. Native Americans, African-Americans, biracial characters. Asperger's, autism, mental retardation. Rape. Date rape. Murder.

All these things were forbidden, all these topics were locked away, so that any YA reader who had questions/concerns/anxieties about them had to look for the answers somewhere else, hopefully from an informed adult with good information delivered sympathetically, but more likely not.

Margo Rabb: The books that I read as a teenager were so incredibly important in shaping who I am, in figuring out who I was and who I wanted to be, that I sometimes wonder who I would've become without them. Anne of Green Gables, Jo March, Anne Frank, Scout Finch, Davy from Judy Blume's Tiger Eyes and Kate from Zibby O'neal's In Summer Light were as real to me as my friends and family. They were my role models and heroines, and most of all, they helped me understand all my complex and conflicting emotions--feelings that I didn't understand until I saw them on the page. I learned from Anne of Green Gables that my imagination and dreams were even more important than my reality; from Jo that I yearned to be independent and strong; from Davy that I could survive anything, even the very thing I thought I could never survive; and from Kate that I wanted to be mature and thoughtful when I fell in love.

Now that I'm a mother, I often think about the books that I want my daughter to read. I think that one of the best things my mother did--aside from raising us in a house overflowing with books--was always allowing me to read whatever I wanted. No book was off limits. I was allowed to read Judy Blume's Forever when I was ten years old, and it didn't scar me (if anything, I became the most chaste teenager on the planet.) Books helped me see what I didn't want to become as well, what I wasn't ready for, and what mistakes I wanted to try to avoid making.

What I'm trying to say (in a very roundabout way) is: I think that the heroines in YA fiction are even more important than specific subjects...I think girls need to see themselves on the page, and to see the strong girls they'd like to try to become.

The line between adult books and YA books has become completely fluid and often invisible (I wrote an essay about this subject here*)--while researching the essay, one publisher told me that "There is no subject that is off-limits in YA." I think that the incredible diversity and variety of the genre is amazing--and it thrills me to think of all the strong, complicated heroines in YA books today, and all the ones that will be published in the future.

Jenny Davidson: I am going to take a potentially contrarian view. I do not see why specifically YA fiction is necessary. It strikes me as a publisher's category rather than a writer's one, in many respects, and though I do see that so-called middle-grade books offer something that adult fiction can't mimic, this stops seeming to me true as far as the young-adult category goes.

Do I think that there need to be novels dealing with adolescence, figuring out of sexuality, what it means to grow up in a family, etc.? Yes. But I can't see a real difference between The Fountain Overflows (Rebecca West, published for adults) and Nobody's Family Is Going to Change (Louise Fitzhugh, published for children). There are "classics" that are suitable for teenagers to read (Jane Austen and Dickens come to mind, though I have always found it slightly perverse that people seem to think that Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre is a good book to assign to tenth-grade boys!). There is quite a bit of good contemporary fiction that's published for adults but that's highly suitable for teenagers (I'm thinking of specific examples like Danzy Senna's Caucasia, the novels of Tayari Jones and Joshilyn Jackson, Helen DeWitt's The Last Samurai, Richard Powers' The Time of Our Singing) - and if those are too challenging, well, there's a WORLD of genre fiction out there - whether you like romance or crime or science fiction or fantasy or westerns, there are books written in relatively accessible styles and narrative modes that will give the feel and experience of reading with deep enjoyment to people passing out of the years of childhood but not yet adults.

I'm not saying that YA doesn't make sense as a publishing category. To pick high-quality writers from two different subcategories of YA, Scott Westerfeld and E. Lockhart both have a real feel for writing for teenagers. But could their books be published for adults? Yes, with very few changes; and could the kids that love their books be reading books published for the adult market? Again, certainly.

Melissa Wyatt: What girls can find in YA that they will not find in adult books is an emotional experience more specific to where they are in their lives. But also--for teens more so than anyone else--a book needs to provide a safe place where you can try on emotions. A sort of emotional playground where they can take out ideas and thoughts that they maybe can't talk about with even their closest friends or are even embarrassed to admit and see how it all feels. A place where nobody is watching over their shoulder to tell them they're wrong to think or feel this way. It's the great hiding place and playground of the secret heart-of-hearts.

And it's tough, but I think this is where we have to trust girls and let them read where that need takes them, even if it's something that we don't think is obviously important--or we misunderstand what it is they are getting out of a book. Look at the enormous appeal of books like A Child Called It. I don't think this book is being read in an effort to develop empathy for children in such a terrible situation. I think it's the secret delight of utter utter horror and debasement. That sounds awful. It sounds callous. But it's important. It's a stretching of emotional muscles. It's not why I would read that book, but it's the way I would have read it at fourteen.

So I think this is something that's important to remember when we see girls responding to books that might trouble us for one reason or another. What they're getting from those books may not necessarily be what we--from our adult perspective--might fear. But it could be filling a need only they can define and one they ought to be allowed to pursue in that safe place of the book.

Do teen girls need YA books? Is there something innate in the genre that shapes growing up like nothing else can? Colleen Mondor at Chasing Ray is asking that question today, and some really smart people are offering their perspectives. Here, for example, is Zetta Elliott:

Do teen girls need YA books? Is there something innate in the genre that shapes growing up like nothing else can? Colleen Mondor at Chasing Ray is asking that question today, and some really smart people are offering their perspectives. Here, for example, is Zetta Elliott:

The more YA lit I read, the more I’m struck by the split: novels that are about teens versus novels that are marketed to teens. The latter are often marked by “lite” writing and silly gimmicks that aim to make the novel seem experimental or innovative in terms of form. But real daring resides in the writing itself, and I think teens deserve novels on every topic, told from as many different points of view as possible. Books that offer narrative possibility (instead of filling in all the blanks) open the door for continued conversation, so I’d also say that we need adults who have the courage to face the daunting questions that teens need to ask.

I've contributed my two cents to the conversation as well, for what they are worth, and I encourage you to take a look—and to join in the discussion.

As a corollary to last week's What a Girl Wants entry on race and identity in YA lit, I've been thinking about the question of what it means to be white. When I was teaching (soldiers and dependents at Ft Wainwright, AK) we would discuss ethnicity as part of our survey of war in the 20th century. For a classroom exercise, everyone would identify their own ethnicity. It was always a United Nations in my classes: Native American, African American, Asian American (Cambodian, Filipino, Japanese, etc.), Hispanic (Mexican, Guatemalan, Honduran, etc.), Jamaican, Puerto Rican and on and on. Then we would get to the Caucasian students and always - without fail - the first response would be "I'm white". It always took a few minutes to explain to them that white was a color and really, means nothing at all.

As a corollary to last week's What a Girl Wants entry on race and identity in YA lit, I've been thinking about the question of what it means to be white. When I was teaching (soldiers and dependents at Ft Wainwright, AK) we would discuss ethnicity as part of our survey of war in the 20th century. For a classroom exercise, everyone would identify their own ethnicity. It was always a United Nations in my classes: Native American, African American, Asian American (Cambodian, Filipino, Japanese, etc.), Hispanic (Mexican, Guatemalan, Honduran, etc.), Jamaican, Puerto Rican and on and on. Then we would get to the Caucasian students and always - without fail - the first response would be "I'm white". It always took a few minutes to explain to them that white was a color and really, means nothing at all.

My white students identified more with skin than ethnicity while all of my other students identified much more strongly in the opposite manner. It did not occur to any of them to say they were black or brown - they preferred to discuss how they were raised, where they were born or what their families taught them. There was a lot of head shaking as we discussed what it meant - and didn't mean - to be white. After the first few times I knew to expect it, and was ready to ask the questions about where their parents and grandparents were from and tease out the immigrant stories that everyone has (no matter how far back you have to go).

I've been thinking about my students a lot lately as I put together the post on minority characters in YA lit. While there is certainly a dearth of such characters in most teen novels (which is why I posed last week's question) there is also something very odd going on in novels with Caucasian protagonists. It has been ages since I've read a YA novel that is not pointedly about minorities where the characters are described as anything other than just white. There is no mention of a religion (even so much as a sentence about going to church, synagogue, etc.) or culture or any kind of ethnic clues at all. There is a blandness to these books - and these characters - that would seem to defy the way most of us live. It is not that I expect ethnicity to be part and parcel of every novel - plots do not need to revolve around it - but I can't possibly be the only person in the country who grew up with a parent that spoke endearments in his native language (my father first language was French) or enjoyed a cup of tea served the Irish way by my grandmother. Also, as someone half Irish and half French Canadian, I came from a very Roman Catholic background. While we may not have discussed God on a daily basis (please) we were in church every Sunday, every funeral is a Catholic Mass and every member of my family (except for my generation) carried rosaries on their person pretty much all the time. (I imagine my mother still carries some sort of religious medal or rosary in her purse somewhere, if for no other reason then to honor her parents.)(I do the same thing.) There is food that we ate, stories we told and sports we watched (the Montreal Canadians were my father's saints) that we all related to our ethnicity. And everyone I know lived this way to one degree or another. But that's not the world I've been reading about and I'd love to know why.

Author Alma Alexander raised something similar to this in one of her comments last week about white authors: "There is such a breadth of human experience out there. Just as I don't for a moment believe that there is a generic "black experience", I believe at the same time that a reverse error is often made when people speak of "white writers" - WHICH white writers? A Swedish writer? A British writer? A Greek writer? Someone from Sydney...? Rome...? Chicago...? Just what EXACTLY are all those wildly diverse "white" writers supposed to have in common to write about in terms of "white experience"?"

I see a similar catch-all of "white experience" for characters. There is a misconception that being white is a totality of experience by itself and yet, and yet, really that is not true. Again, in my classes I would divide the classes to break down what made us different and what made us the same. First we split by race (Caucasian and non Caucasian) as that was how the class saw themselves most different. But then I asked them to divide by who had given birth and who hadn't which led to a lot of comments from every mother in the class saying that unless you had done that you didn't know anything about pain. (This was usually a huge mood lightener which was the chief reason why I did it.) From there we split on region (westerners thought they were cooler, easterners smarter, northerners tougher, southerners claimed bbq - and no one could argue that.) We split on who had lost a parent, who had survived cancer, who loved Star Trek vs who hated it. Things always got a little goofy but the point, as everyone walked back and forth across the room, was that there were a lot of things we had in common that transcended race. Skin color was just skin color and in the grand scheme of things only part of who we are.

Which wasn't really news to anyone but something that became so obvious no one in the class could ignore it.

In reading most YA novels for girls these days the protagonist is some generic white girl whose parents do an indefinable job for a living, lives in a house or apartment that is easily paid for, and has nondescript features that are either beautiful, mousy, appealing, understated, or plain....depending on the book's message. She goes to school, she has friends, she has drama. She is sick or someone she loves is sick. She is in love or pines for love. She is bright and appreciated or shy and unnoticed. She is the obvious heroine or becomes one by the end. But regardless of all those plot points, she rarely has any aspect of her life that lets the reader know the slightest thing about who her people are or where they came from.

We might as well be reading glorified versions of Dick and Jane for all these books really tells us.

I bring this up not to suggest that white characters are in some sort of competition with minority ones, but rather to show that homogeneity is more the order of the day in our stories then we imagine. Part of why it might be more difficult for minority characters to break through is because white characters are so blank that any character with any ethnic sensibility (even when it is only descriptive and not the point of the story) stands way out. The point is to make the characters to identifiable to all readers (or who the publishers want them to appeal to) that they have become not everyone but no one. It's all about blonde and white and middle class. And beyond that, well beyond that you pretty much might as well be an illegal immigrant for all that these books tell us about ourselves.

I hated Dick and Jane, by the way. What bloody boring stories. That's not the world I grew up in and I don't understand why it still pervades our reading experience today.

[Post pic: my father and grandfather - proud French Canadians. Circa 1942. My father was the first one in his paternal family to be born in this country.]

Colleen Mondor at Chasing Ray has inspired another interesting discussion about teen girls and reading. This time, Colleen asked us panelists to discuss how important it is (or isn’t) for writers to identify with their protagonists. Specifically, she asked:

Do you think writers and publishers address this identity issue strongly enough and in a balanced manner in current teen fiction?

Can authors write characters of different race/ethnicity or sexual preference from their own?

Beyond that, what special responsibility, if any, do authors of teen fiction have to represent as broad a swath of individuals as possible?

You can read the thoughtful responses of Colleen’s WAGW Panel here.

I tackled the question from a non-fiction point of view, of course, and only the issue of identifying with my subject as an author. I also linked over to a similar discussion that was started at the I.N.K. (Interesting Nonfiction for Kids) blog. If you feel strongly on these topics, do stop by and join in the discussions.

In the meanwhile, I’m rubbing my hands together in anticipation of reading three new titles in Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Scientists in the Field series. Together these books share the work of five scientists, among them a female microbiologist/spelunker and an African American biologist:

As a reviewer of MG and YA literature one of the things I have struggled with is to include diversity in my columns. It is difficult enough to include a balance of books between male and female protagonists but if you throw in having a fair number of titles with minority characters then it really gets tough. In the sea of titles with straight white female (blonde) main characters, there are disturbingly few that are African American, Native American, Jewish, Muslim, Asian American, Indian, LBGT and on and on. In some ways, it is a chicken and egg problem however - are their fewer teen books published with minority characters because publishers do not think they will sell or is the problem that writers capable of crafting such books from their own experience are uncommon?

As a reviewer of MG and YA literature one of the things I have struggled with is to include diversity in my columns. It is difficult enough to include a balance of books between male and female protagonists but if you throw in having a fair number of titles with minority characters then it really gets tough. In the sea of titles with straight white female (blonde) main characters, there are disturbingly few that are African American, Native American, Jewish, Muslim, Asian American, Indian, LBGT and on and on. In some ways, it is a chicken and egg problem however - are their fewer teen books published with minority characters because publishers do not think they will sell or is the problem that writers capable of crafting such books from their own experience are uncommon?

In other words - are white writers (who are in the majority) afraid to write books with minority characters or are minority authors prevented from being published because the kids they write about don't have the purchase power of the white kids?

These are complicated questions and there are no easy answers. However no one can argue that there is a glaring lack of books for teens with minority characters. It is ridiculous how many books are published each season with characters who look the same, sound the same and come from the same economic circumstance. Something needs to change. The questions put to the group this time addressed this issue in several ways. Do you think that writers and publishers address this identity issue strongly enough and in a balanced matter in current teen fiction? Can authors write characters of different race/ethnicity or sexual preference from their own and beyond that, what special responsibility, if any, do authors of teen fiction have to represent as broad a swath of individuals as possible? Here are their very well considered, deeply personal and fascinating answers (please note the book covers depicted are either mentioned in their answers or titles with minority protagonists I highly recommend):