By Kirk Curnutt

Ask folks who came of age in the 1980s what they remember about the movie Eddie and the Cruisers and one of the following responses is likely:

- It spawned the great rock-radio staple “On the Dark Side” and briefly made MTV stars of the improbably named John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band.

- It was such a shameless Bruce Springsteen rip-off that Boss fans considered it as sacrilegious as devout Christians do Jesus Christ Superstar.

- It had a whiplash-inducing twist ending that Roger Ebert called “so frustrating, so dumb, so unsatisfactory that it gives a bad reputation to the whole movie.”

- It was a box-office flop that thirty years ago this month shocked Hollywood by becoming a surprise HBO hit.

- It was a movie you rented repeatedly during the decade’s video boom because it fit perfectly VHS’s promise of cheap home entertainment: undemanding, toe-tapping, and eminently re-watchable, it was an ideal 99-cent diversion that helped you forget VCRs cost $500 and were as boxy as Samsonite suitcases.

What you’re less likely to hear, unfortunately: it was based on one of the best, most criminally underappreciated rock ‘n’ roll novels ever.

In a preface to Overlook Press’s 2008 reissue (the book’s first widely available trade paperback), no less than Sherman Alexie admits he never knew Eddie was originally a novel by P. F. Kluge until deep into his own career, long after “obsessing” over the movie as a high-schooler. It’s indicative of how the film overshadows its source material that Kluge’s Eddie doesn’t even make this supposedly comprehensive list of rock novels published since the 1950s.

The novel’s relative obscurity is a shame, for as Alexie notes, it has literary “ambitions and secrets and qualities” that far surpass the movie’s “mainstream” pleasures. Director Martin Davidson, who co-wrote the script with his wife, Arlene, made several changes to Kluge’s tale of a Jersey rock star who may or may not be haunting former bandmates twenty years after his supposed death. The most significant is seemingly the most cosmetic. Whereas Kluge conceived hero Eddie Wilson as a Dion-esque doo-wop rocker, Davidson turned him into an awkward splice of Springsteen and Jim Morrison. In so doing, the filmmaker altered the literary inspiration that in Kluge gives the musician a model for imagining rock ‘n’ roll as an art form instead of mere entertainment. The change is decisive to how differently each version of Eddie depicts the purpose of popular music.

Une saison en enfer, Arthur Rimbaud, Bruxelles, Alliance typographique, 1873. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the movie, college dropout Frank “Wordman” Ridgeway, the story’s Nick Carraway, introduces Eddie to the 19th-century French symboliste Arthur Rimbaud. Literature spurs the hunky frontman to make “serious” music instead of cranking out bar-band favorites for Jersey beachgoers: “I want songs that echo,” Eddie insists. “The [music] we’re doing now is like bed sheets. Spread ’em, soil ’em, ship ’em out to laundry. Our songs — I like to fold ourselves up in them forever.” Soon enough, Eddie pens a concept album called A Season in Hell, after Rimbaud’s most famous work. His slimy record-company owner refuses to release it, however, because the music sounds “like a bunch of jerkoffs making weird sounds.” The rejection sends Eddie squealing away in his ’57 Chevy, which hurtles off the Raritan Bridge, either an accident or a suicide. The Cruisers are forgotten for two decades later until an Entertainment Tonight-type reporter begins hyping Hell as an ominous foreshadowing of the late sixties, “a new age, an age of confusion, an age of passion, of commitment!” Suddenly, someone claiming to be the dead rock star is stalking the surviving Cruisers, intent on finally releasing the missing opus so the public can recognize Eddie’s brilliance.

Serious scholarly papers have drawn parallels between Eddie and Rimbaud, but the script’s invocation of the poet never really rises above literary window dressing. Davidson mainly uses Rimbaud to allude to Morrison, who idolized the literary libertine and who, according to a farcical urban legend, faked his 1971 death to escape the rock biz (much as Rimbaud abandoned literature before he was twenty). The movie asks us to believe that the Beatlemania-era Eddie predicted the Dionysian extremes of the Doors’ “The End” or (God help us) “Horse Latitudes,” but the song that’s supposed to illustrate his visionary genius, “Fire,” hardly qualifies as “weird sounds”. It’s merely an arthritic gloss on Springsteen’s “Adam Raised a Cain” with none of the Boss’s blistering vitality.

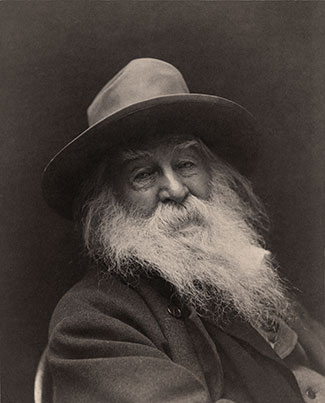

Walt Whitman. Photo by George C. Cox, restoration by Adam Cuerden. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

For Kluge’s Eddie, by contrast, the spirit father isn’t Rimbaud but Walt Whitman, and Eddie’s magnum opus is Leaves of Grass. Having seen Leaves appropriated to do everything from woo interns to expose unlikely meth kingpins, I’ll be the first to say that the Good Gray Poet’s popularity as the Go-To Lit Reference sometimes leaves me craving a Longfellow revival. Yet his role in Kluge isn’t gratuitous. Whitman inspires Eddie to reimagine rock ‘n’ roll as the vox populi, a medium not for becoming famous but for creating the true song of democracy. To produce his rock version of Leaves, Eddie recruits black and white greats from Elvis to Sam Cooke to Buddy Holly (the novel is set in 1957-58, a half-decade earlier than the film). Their mission is to snip the American barbed wire of segregation through a series of secret jam sessions designed to “to bring off the impossible, some fantastic union of black and white music.” What breakthroughs Eddie achieved before his supposed death is as compelling a page-turner as the mystery of who’s harassing the surviving Cruisers. (Spoiler alert: Eddie does not predict “Ebony and Ivory”).

In ditching Whitman for Rimbaud, Davidson’s film became a story not about the Gordian knot of race in American music but about rock-star greatness and fame. That point is bashed home like a gong by the movie’s trick ending, which reveals Eddie is indeed alive but indifferent to the hullaballoo the media creates when his masterwork is finally released. Despite the adaptation’s defects, Kluge speaks appreciatively of it, and rightly so: as a cult favorite, the movie kept the novel’s name alive during the decades the book was out of print. Besides, when the other movie based on your writing is Dog Day Afternoon, you can afford to be generous.

Nevertheless, the lack of attention Book Eddie receives feels like a missed opportunity for rock novels in general. The genre is a diverse, unruly one. Some of its entries are romans à clef that do little more than pencil fictional names into legends rock fans already know by heart (Paul Quarrington’s Brian Wilson-retelling Whale Music). Many others are coming-of-age novels in which that form’s traditional theme of lost innocence plays out like a Behind the Music episode, all downward-spiral cocaine and coitus. Still others are less about music-making than about the grotesquery of fame and fan worship (Don DeLillo’s Great Jones Street). What rock novels aren’t nearly as often about is race — or, at least, the alchemies of ethnic interchange explored in such great nonfiction music histories as Peter Guralnick’s Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom (1986). A handful of exceptions do come to mind, Alexie’s own Reservation Blues (1995) most notably. Yet for the most part storylines about ahead-of-their-time geniuses predominate, and frankly, the plot of making personal art instead of appeasing a hits-happy public is as tired as the playlist at my local oldies station.

The idea of rock ‘n’ roll as both the promise and impasse of a racially egalitarian barbaric yawp, on the other hand… That’s a song in fiction we still don’t hear nearly enough.

Kirk Curnutt is professor and chair of English at Troy University’s Montgomery, Alabama, campus, where Scott Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre in 1918. His publications include A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald (2004), the novels Breathing Out the Ghost (2008) and Dixie Noir (2009), and Brian Wilson (2012). He is currently at work on a reader’s guide to Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not. Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Roll over, Rimbaud: P. F. Kluge, Walt Whitman, and Eddie and the Cruisers appeared first on OUPblog.