new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: nineteenth century, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 17 of 17

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: nineteenth century in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: John Priest,

on 10/17/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Literature,

Data,

ireland,

nineteenth century,

Nineteenth Century Literature,

irish lit,

nineteenth century europe,

nineteenth century ireland,

ordinance survey,

*Featured,

big data,

Arts & Humanities,

european literature,

Cóilín Parsons,

data science,

Irish Literature,

Add a tag

Initially, they had envisaged dozens of them: slim booklets that would handily summarize all of the important aspects of every parish in Ireland. It was the 1830s, and such a fantasy of comprehensive knowledge seemed within the grasp of the employees of the Ordnance Survey in Ireland.

The post Big data in the nineteenth century appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lizzie Furey,

on 3/12/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

letters,

America,

letter writing,

Thomas Jefferson,

nineteenth century,

*Featured,

nineteenth-century America,

The Edinburgh Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Letters and Letter-Writing,

Add a tag

Nowadays letter-writing appeals to our more romantic sensibilities. It is quaint, old-fashioned, and decidedly slower than sending off a winking emoji with barely half a thought. But it wasn't even that long ago that letter-writing dominated and served as a practical means of communication.

The post Nineteen things you never knew about nineteenth century American letters appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 11/26/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

France,

BBC,

drama,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Impressionism,

french literature,

nineteenth century,

Timelines,

Emile Zola,

French History,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

rougon-macquart,

Arts & Humanities,

Glenda Jackson,

l'assommoir,

BBC Radio Four,

Dreyfus,

Add a tag

To celebrate the new BBC Radio Four adaptation of the French writer Émile Zola's, 'Rougon-Macquart' cycle, we have looked at the extraordinary life and work of one of the great nineteenth century novelists.

The post The life and work of Émile Zola appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Connie Ngo,

on 7/6/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

Videos,

adaptation,

film adaptations,

Oxford World's Classics,

Gustave Flaubert,

french literature,

nineteenth century,

Madame Bovary,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

flaubert,

book vs movie,

Bovary,

Emma Bovary,

Emma Rouault,

Add a tag

The tragic story of Madame Bovary has been told and retold in a number of adaptations since the text's original publication in 1856 in serial form. But what differences from the text should we expect in the film adaptation? Will there be any astounding plot points left out or added to the mix?

The post Capturing the essence of Madame Bovary appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 4/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

darwin,

principia,

1830,

History,

Literature,

Education,

Philosophy,

knowledge,

British,

Charles Darwin,

Humanities,

nineteenth century,

thomas carlyle,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

origin of species,

Science & Medicine,

James Secord,

UKpophistory,

Thomas De Quincey,

british victorian history,

Charles lyell,

cultural transformation,

Jim Secord,

set text,

secord,

quincey,

Add a tag

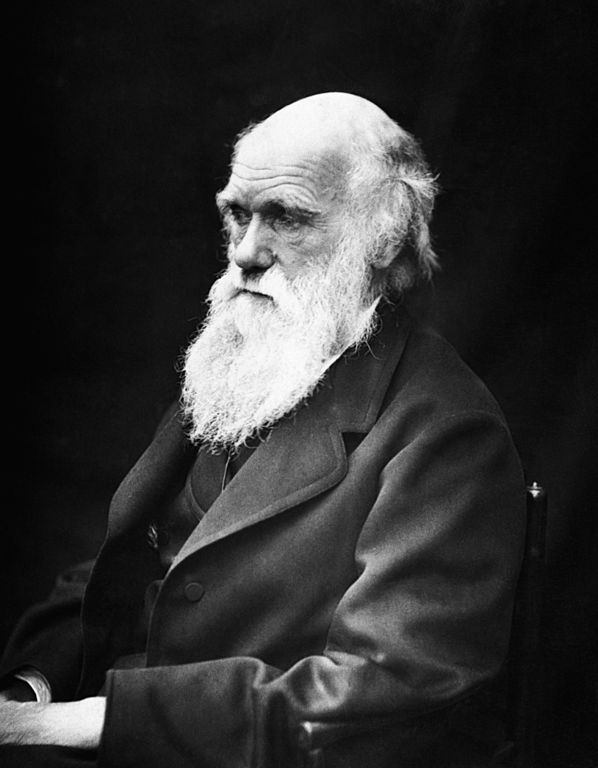

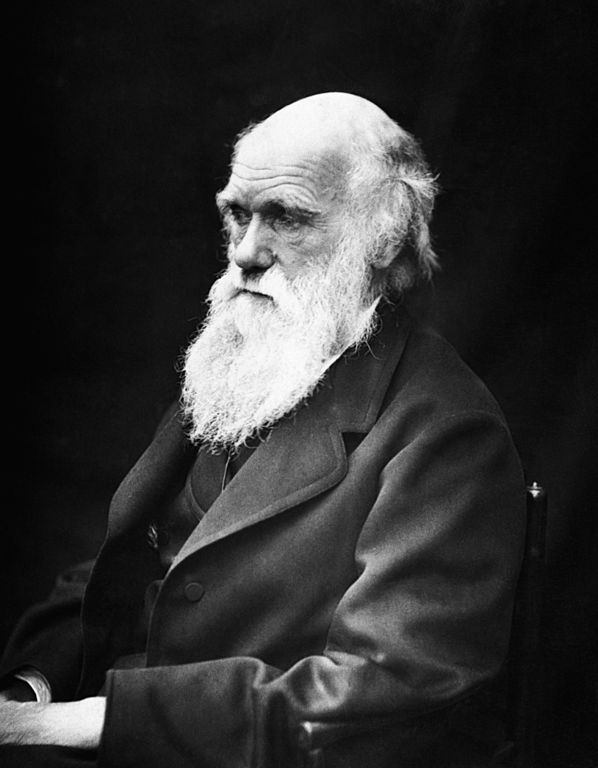

By James Secord

We tend to think of ‘science’ and ‘literature’ in radically different ways. The distinction isn’t just about genre – since ancient times writing has had a variety of aims and styles, expressed in different generic forms: epics, textbooks, lyrics, recipes, epigraphs, and so forth. It’s the sharp binary divide that’s striking and relatively new. An article in Nature and a great novel are taken to belong to different worlds of prose. In science, the writing is assumed to be clear and concise, with the author speaking directly to the reader about discoveries in nature. In literature, the discoveries might be said to inhere in the use of language itself. Narrative sophistication and rhetorical subtlety are prized.

This contrast between scientific and literary prose has its roots in the nineteenth century. In 1822 the essayist Thomas De Quincey broached a distinction between the ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power.’ As De Quincey later explained, ‘the function of the first is to teach; the function of the second is to move.’ The literature of knowledge, he wrote, is left behind by advances in understanding, so that even Isaac Newton’s Principia has no more lasting literary qualities than a cookbook. The literature of power, on the other hand, lasts forever and draws out the deepest feelings that make us human.

The effect of this division (which does justice neither to cookbooks nor the Principia) is pervasive. Although the literary canon has been widely challenged, the university and school curriculum remains overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of key authors and texts. Only the most naive student assumes that the author of a novel speaks directly through the narrator; but that is routinely taken for granted when scientific works are being discussed. The one nineteenth-century science book that is regularly accorded a close reading is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). A number of distinguished critics have followed Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots in attending to the narrative structures and rhetorical strategies of other non-fiction works – but surprisingly few.

It is easy to forget that De Quincey was arguing a case, not stating the obvious. A contrast between ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power’ was not commonly accepted when he wrote; in the era of revolution and reform, knowledge was power. The early nineteenth century witnessed remarkable experiments in literary form in all fields. Among the most distinguished (and rhetorically sophisticated) was a series of reflective works on the sciences, from the chemist Humphry Davy’s visionary Consolations in Travel (1830) to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33). They were satirised to great effect in Thomas Carlyle’s bizarre scientific philosophy of clothes, Sartor Resartus (1833-34).

These works imagined new worlds of knowledge, helping readers to come to terms with unprecedented economic, social, and cultural change. They are anything but straightforward expositions or outdated ‘popularisations’, and deserve to be widely read in our own era of transformation. Like the best science books today, they are works in the literature of power.

James Secord is Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project, and a fellow of Christ’s College. His research and teaching is on the history of science from the late eighteenth century to the present. He is the author of the recently published Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post When science stopped being literature appeared first on OUPblog.

What a good story The Black Spider by Jeremias Gotthelf turned out to be. What’s not to like about a story with the Devil himself and spiders in it? It was even a little creepy at times.

The story begins with a christening. After much eating, the celebrants push themselves away from the table for a little walk to make room for more food. One of them notices an old black post in the window frame of this lovely new house and asks Grandfather about it. And boy, does Grandfather have a tale to tell!

Long ago a powerful knight named Hans von Stoffeln took possession of the land and the peasants of the area. He decided he needed a new castle, bigger and better than the old one, and forced the peasants to build it for him on top of a barren hill. After long and hard labor during which the peasants were forced to neglect their own fields and families and come near to starvation, the castle was finished. But the knights made fun of von Stoffeln and his castle on the barren hill, so von Stoffeln decided he needed an avenue of one hundred trees. He ordered the peasants to uproot trees from miles away and bring them to the castle and plant them in an avenue. This work had to be done within a month’s time. The peasants were beside themselves, worn out and hungry their carts and tools and animals on the verge of falling apart and collapse, what were they to do?

Suddenly in their midst appears a hunter dressed in green with a “beard so red it seemed to crackle and sparkle like fir twigs on the fire.” He offers to help but the peasants, unable to see how a huntsman could help them, refuse. The green man chides them, tells them he can make their work fast and easy for only a small payment: an unbaptized child. Horrified, the peasants refuse again.

The next day they begin their work and it quickly becomes clear that they will not be able to complete the task in the allotted time. But Christine, a “frightfully clever and daring woman” decides that they can beat the Devil at his own game and convinces the men to agree to the offer of help. The Devil seals it with a kiss on Christine’s cheek. Suddenly the work becomes easier and the peasants complete their task so quickly that they have time to start work in their own fields.

But soon the time for the first baby to be born draws near. Christine, who is the midwife, plans on having the priest present at the birth so the baby can be immediately baptized and saved from the Devil’s clutches. The plan works. But then Christine’s cheek where the Devil had kissed her starts burning. A small black mark appears on it. As the time for the birth of the next baby arrives the black mark has grown bigger. As the woman gives birth inside the house with the Priest present, Christine is outside in the midst of her own labor except instead of birthing a baby, she gives birth to one large spider and thousands of tiny ones from the black mark on her face. It is a gruesome scene:

And now Christine felt as if her face was bursting open and glowing coals were being birthed from it, quickening into life and swarming across her face and all her limbs, and everything within her face had sprung to life, a fiery swarming all across her body. In the lightning’s pallid glow she saw, long-legged and venomous, innumerable black spiderlings scurrying down her limbs and out into the night, and as they vanished they were followed, long-legged and venomous, by innumerable others.

These spiders first killed all the peasants’ livestock. And the peasants, placing all the blame on Christine, now start to plan on how to get their hands on the next baby before the priest can baptize it.

Isn’t this a delicious story? You will have to read it yourself to find out what happens and what it has to do with the black post at the beginning of the story. It is safe to say that the Godly win. And, of course, as long as the people in the valley remain Godly they have nothing to fear from the spider. We are reminded that inborn purity, like family honor,

must be upheld day after day, for a single unguarded moment can besmirch it for generations with stains as indelible as bloodstains, which are impervious to whitewash.

Of course it is the clever woman, Christine, who persuades the men to allow evil into the community. And generations later when the spider strikes again it is also women who are at the root of its reappearance. But you know Eve set the precedent in the Garden so the fault is always with the women because men just can’t say no to their persuasive powers. Given that the story was originally written in 1842 the sexism can be noted but tolerated and the story enjoyed for its delicious horrors.

I can chalk this one up as another RIP Challenge read as well as mark it down as my NYRB subscription October read. Woo! Two birds, one stone and all that. The Mysteries of Udolpho is almost done too. Next week for sure. I’d say I am doing really well with my October reading plan but I don’t want to jinx myself. Oops, I think I just did.

Filed under:

Books,

Challenges,

Gothic/Horror/Thriller,

Nineteenth Century,

Reviews Tagged:

Jeremias Gotthelf,

NYRB Classics

By: Nicola,

on 12/12/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

Psychology,

charles dickens,

200th anniversary,

Humanities,

nineteenth century,

victorian poet,

the poet's mind: the psychology of victorian poetry 1830-1870,

the ring and the book,

browning’s,

oddness,

*Featured,

dickens 2012,

@drgregorytate,

alfred tennyson,

bicentary,

browning society,

gregory tate,

robert browning,

browning,

Add a tag

By Gregory Tate

This year marked the bicentenary of the birth of the Victorian poet Robert Browning in 1812, although this news might come as something of a surprise. The bicentenary of Browning’s contemporary Charles Dickens was celebrated with so many exhibitions, festivals, and other events that an official Dickens 2012 group was set up to co-ordinate and keep track of them all. The writings of Alfred Tennyson, Browning’s (consistently more popular) rival, also cropped up in some high-profile places throughout the year. But although academic specialists and other Browning enthusiasts organised conferences and special publications in 2012, media commentators and cultural institutions remained almost wholly silent about the Browning anniversary.

There are many possible reasons for this silence. There’s the issue of religion: Browning’s robust Christian faith, and his love of abstruse theological speculation, are perhaps less congenial to twenty-first-century tastes than the yearning doubt of Tennyson or the pious sentimentality of Dickens. Browning’s habit of writing poems about arcane subjects (such as the thirteenth-century troubadour Sordello or the sixteenth-century alchemist Paracelsus) might also alienate readers. The reason might, however, be something even more fundamental: Browning’s poetry is difficult, and discomfiting, to read. When Browning was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey on 31 December 1889, Henry James wrote that “a good many oddities and a good many great writers have been entombed in the Abbey; but none of the odd ones have been so great and none of the great ones so odd.” For James, Browning’s oddness was an essential part of his poetic achievement. Today, it seems, the general view (if there is a general view on him at all) is that his oddness precludes greatness.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

Browning’s approach is exemplified in what is arguably his greatest poem, The Ring and the Book (1868-1869), a psychological epic which recounts the events of a seventeenth-century murder case from nine different perspectives. Browning sets out to integrate these conflicting perspectives into an authoritative and morally educational account of the murder, describing them as:

The variance now, the eventual unity,

Which make the miracle. See it for yourselves,

This man’s act, changeable because alive!

Action now shrouds, now shows the informing thought.

The poem’s concern is not with the murder itself, “this man’s act”, but with tracing “the informing thought,” the motive behind the act. This poetic analysis of thought, Browning argues, enables the synthesis of conflicting accounts into an “eventual unity,” and the dense style of his verse is a key element of this process. “Art,” he states “may tell a truth / Obliquely, do the thing shall breed the thought.” By testing and confounding his readers, Browning’s difficult (and odd) poetry invites them to think carefully about the minds of other people, breeding new thoughts and telling oblique truths.

In The Ring and the Book Browning addresses the “British Public, ye who like me not.” The publication of this poem, however, marked a sea change in Victorian opinions of the poet. In the 1870s and 1880s his writing was admired simultaneously for its evident Christianity and its intellectual richness, and he was venerated as a sage and a moral teacher by the Browning Society which was founded in 1881 to study and champion his work. He was also celebrated, by Henry James and by Modernists such as Ezra Pound, as (in James’s words) “a tremendous and incomparable modern.” In 2012, though, Browning’s modernity and relevance have not been sufficiently emphasised. This is a shame, because, in his psychological sophistication and in his awareness of the complexities and limitations of language, he still has truths to tell to the British public, who like him not. Those truths, and Browning’s poems, might be oblique and difficult, but they’re worth the effort.

Gregory Tate is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Surrey. His book, The Poet’s Mind: The Psychology of Victorian Poetry 1830-1870, was published by OUP in November 2012. You can follow him on Twitter @drgregorytate.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Robert Browning. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Robert Browning in 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

You already know about Dickens making frequent use of repetition in A Tale of Two Cities and you also know how much I was enjoying it. Now that I have finished I am not sure what else to say. Fantastic. A page turner. Two thumbs up. Let’s see what else I can winkle out of it.

You may or may not know, that the two cities are London and Paris and that the story takes place during the lead up to and as far as the middle of the French Revolution. We start out going back and forth between London and Paris and eventually all things converge on Paris where the various tributaries of the story finally merge into one rushing river.

I realized that Dickens, in all his exuberance, really is the master of small, seemingly inconsequential details or characters turning out to be important later on. I know he wrote his books for serial publication, but he must have had an outline ahead of time to be able to work the plot marvels that he does.

Dickens, we all know, is quite good at describing the downtrodden:

The mill which had worked them down, was the mill that grinds young people old; the children had ancient faces and grave voices; and upon them, and upon the grown faces, and ploughed into every furrow of age and coming up afresh, was the sigh, Hunger. It was prevalent everywhere.

Those are the poor in Paris who will later rise up, and in a breathtaking scene, take the Bastille. I cheered. I loved the Defarges and all the Jaques, I was terrified one or more would die. And even in the aftermath I continued to be afraid for them. But then things begin to turn as those who were oppressed become the new oppressors and set about killing as many who belonged to the aristocracy or had any association with them as they possibly can. Anyone who questions what is happening is a sympathizer and also sent to the guillotine:

Above all, one hideous figure grew as familiar as if it had been before the general gaze from the foundations of the world—the figure of the sharp female called La Guillotine. It was the popular theme for jests; it was the best cure for headache, it infallibly prevented the hair from turning grey, it imparted a peculiar delicacy to the complexion, it was the National Razor which shaved close: who kissed La Guillotine, looked through the little window and sneezed into the sack.

And so those with whom I was so sympathetic to begin with slowly become cruel and horrible people. Madame Defarge is the one it was most distressing to see change. She is a strong, female character who plots and plans with her husband, is equal to her husband, who leads a charge of women against the Bastille. She is

Of a strong and fearless character, of shrewd sense and readiness, of great determination, of that kind of beauty which not only seems to impart to its possessor firmness and animosity, but to strike into others an instinctive recognition of those qualities; the troubled time would have heaved her up, under any circumstances. But, imbued from her childhood with a brooding sense of wrong, and an inveterate hatred of a class, opportunity had developed her into a tigress. She was absolutely without pity. If she had ever had the virtue in her, it had quite gone out of her.

It is that sense of wrong that she has harbored nearly all her life that turns her from being a sympathetic character into zealot who doesn’t know when to stop. It is terribly frightening and sad. And I think with her and the residents of St. Antoine (the district of the most violent uprising), Dickens has shown us how this story of the French Revolution is still relevant today; how one can assume that because a person belongs to Group A he must therefore be bad because Group A is the enemy. There is no account taken of individuals, no bothering to notice that some people in the hated group are supporters of the other group&rsq

In that far-off time superstition clung easily round every person or thing that was at all unwonted, or even intermittent and occasional merely, like the visits of the pedlar or the knife-grinder. No one knew where wandering men had their homes or their origin; and how was a man to be explained unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother? To the peasants of old times, the world outside their own direct experience was a region of vagueness and mystery: to their untravelled thought a state of wandering was a conception as dim as the winter life of the swallows that came back with the spring; and even a settler, if he came from distant parts, hardly ever ceased to be viewed with a remnant of distrust.

George Eliot has been added to my list of writers with amazing powers of description who know just the perfect detail that evokes so much more. The quote above is about the town of Raveloe where Silas Marner, a stranger to the town, arrives after being betrayed by those he trusted most. Marner is a weaver, a very good weaver, and he sets up house in a little place on the edge of a deserted stone-pit. It suits him just fine to be all alone. He’s been deeply wounded by the betrayal and the only interactions he wants to have with people are in relation to his work. He doesn’t do anything to earn the trust of the community, to try and fit in or make friends. He is so solitary and hunched and near-sighted from all his weaving that he looks older than he is and not a little bit crazy.

He used to be an outgoing and friendly man who gave a good portion of his earnings to his church. But now, in his solitude, his earnings have nothing to be spent on and Marner turns into a miser, hoarding his coins and taking pleasure in watching their number increase.

And then his money is stolen. But soon after the theft of his gold guineas, a golden-haired child arrives at his hearth, her mother dead nearly on Marner’s doorstep. Marner calls her Eppie after his much-loved and deceased younger sister. Eppie becomes Marner’s salvation and redemption:

By seeking what was needful for Eppie, by sharing the effect that everything produced on her, he had himself come to appropriate the forms of custom and belief which were the mould of Raveloe life; and as, with reawakening sensibilities, memory also reawakened, he had begun to ponder over the elements of his old faith, and blend them with his new impressions, till he recovered a consciousness of unity between his past and present.

Eppie rescues Marner from his solitude, brings him back to life, connects him to the town of Raveloe. Marner believes that his lost money was actually a payment of sorts for Eppie. And Eppie of course grows into a kind and beautiful young woman.

But Marner is faced with one more test, as is Eppie. Eppie’s “real” father comes to claim her. He is a well-respected, comfortably situated man in Raveloe who knew all along Eppie was his child but didn’t dare say anything for a variety of selfish reasons. Marner doesn’t want to give Eppie up but he wants what is best for her and understands that her biological father could give her much more than he ever could. So he tells Eppie that if she wants to go she can. Eppie’s love for Marner never waivers for a second, she and Marner will not be separated. And so they are rewarded with the return of the money that was stolen all those years ago, found on a dead man when the water at the bottom of the stone-pit was drained for irrigation purposes.

Silas Marner is one of those wonderful stories in which everyone gets what they deserve. This means it is heavily moralistic, but the writing itself is so marvelous that I mostly didn’t mind. How could I mind with descriptions like this:

Mrs. Crackenthorp—a small blinking woman, who fidgeted incessantly with her lace, ribbons, and gold chain, turning her head about and making subdue

Are there many people who haven’t seen one of the many adaptations of H.G. Wells’ book War of the Worlds? When I was a kid I saw the old black and white movie version on some Saturday afternoon TV program that ran old movies. I also knew about the Orson Welles’ radio adaptation that scared the pants off quite a few people when it aired because they had missed the beginning and thought it was real. And then of course there is the movie The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension in which it is discovered that Welles’ radio play was not fiction, but that aliens had indeed landed and have been living among us. And even if you have never seen a movie version you still probably know the plot:

Martians invade. Kill a lot of people. Humans are helpless against them. Things look grim. But then the Martians catch the flu or the common cold or some other earthly bug and they all keel over. Humanity wins!

While the book is definitely a fun, and short, Victorian page-turner, there are still some interesting things that go on in it. Humanity doesn’t have the ability to fight back. Our weapons are pretty much useless against the Martians and their heat-ray and black clouds that kill instantly. And at one point the narrator has an epiphany:

For that moment I touched an emotion beyond the common range of men, yet one that the poor brutes we dominate know only too well. I felt as a rabbit might feel returning to his burrow and suddenly confronted by the work of a dozen busy navvies digging the foundations of a house. I felt the first inkling of a thing that presently grew quite clear in my mind, that oppressed me for many days, a sense of dethronement, a persuasion that I was no longer a master, but an animal among the animals, under the Martian heel. With us it would be as with them, to lurk and watch, to run and hide; the fear and empire of man had passed away.

But while he feels beaten down he is still determined to survive. He spends time with a curate who goes increasingly insane wondering what sins humanity had committed to deserve such wrath from God. Our narrator ends up aiding in the curate’s death by Martian and only feels mildly guilty about it because he had done it in order to save his own life.

Our narrator also spends time with an artilleryman who has escaped death and who goes on and on about how the two of them will put together a rebel group of humans who will live underground and survive while all the people who are “useless and cumbersome and mischievous” can just die. Our narrator goes along for a little while until he realizes that the artilleryman is as nutty as the curate.

When the Martians finally die, the epiphany goes out the window. Suddenly humans deserved to live because we had been fighting a war already for all those hundreds of years against the bacteria that killed the Martians. Humans deserved to live because

By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain.

And then our narrator imagines the human race going out into space and conquering new worlds!

The one thing that bothered me about the book is that the narrator dumps his wife at the cousin’s in Leatherhead and then spends the rest of the book without her. Oh, he insists that he is trying to get to Leatherhead but each time he says that he ends up going in the opposite direction and eventually ends up in London where he still is when the Martians die and where he still insists that he is trying to get to Leatherhead. His wife survives. He goes to their house near Woking and she shows up looking to see if he is still alive. We are then supposed to believe

Yesterday I left off talking about how Bleak House is a novel about “the system.” The idea of the system was relatively new at the time, at least to the general public. But to Dickens, it probably only brought further clarification to what he had been writing about all along. With the concept of a system, rather than an individual problem, an issue like poverty suddenly becomes something bigger and one can start seeing all of the parts and pieces that create it and keep someone who is in it from getting out. Also within a system, we can start looking at how things are connected together, how something over here affects something over there.

In Bleak House Dickens tries to give us a view of both the forest and the trees. We have the Chancery court and the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce that has gone on for so long there are few who can remember what it was all about in the first place. And then we have the current Mr. Jarndyce who wisely stays away from the court and tries to pretend there is no case to which he is a party. Instead he busies himself with taking in three orphans. Two of the orphans, Richard and Ada, are cousins of Mr. Jarndyce, wards of the court, and, as it turns out, a competing party in the suit. The third orphan, Esther Summerson, has a long backstory, but has just finished school compliments of Mr. Jarndyce, and is now brought to Bleak House along with Richard and Ada to be both housekeeper and companion to Ada.

Esther is one of the two narrators of the book. The story moves back and forth between her personal first person narrative and a limited third person narrator. Through Esther’s eyes we watch the long and drawn out coming of age of Richard and his subsequent obsession with the suit followed by a sad ruin as he had pinned all his hopes on getting a settlement out of the suit.

This is the core but there is a cast of dozens and dozens and dozens. And because this is a book about the system, all of these characters at one point or another touch one or more of the other characters in ways that are both expected and unexpected. It is therefore imperative that the reader pays attention to everything because later on it will matter 9I did not know this at first and at time had a hard time figuring out who characters were and what they had done prior to their present appearance). And so it happens that Jo, a poor, homeless orphan boy who gets pennies and half crowns from sweeping and the kindness of a few neighbors, a boy who doesn’t know “nothink,” becomes a pivotal part of the story, touching the lives of the poor and wealthy alike.

The system also has a way of allowing those who work for it to deny having any kind of responsibility for it. Mr. Gridley, a man ruined by the courts says it all:

“There again!” said Mr. Gridley with no diminution of his rage. “The system! I am told on all hands, it’s the system. I mustn’t look to individuals. It’s the system. I mustn’t go into court and say, ‘My Lord, I beg to know this from youis this right or wrong? Have you the face to tell me I have received justice and therefore am dismissed?’ My Lord knows nothing of it. He sits there to administer the system. I mustn’t go to Mr. Tulkinghorn, the solicitor in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and say to him when he makes me furious by being so cool and satisfied as they all do, for I know they gain by it while I lose, don’t I?I mustn’t say to him, ‘I will have something out of some one for my ruin, by fair means or foul!’ HE is not responsible. It’s the system. But, if I do no violence to any of them, hereI may! I don’t know what may happen if I am carried beyond myself at last! I will accuse the individual workers of that system against me, face to face, before the great eternal bar!”

This is not a book in whic

In many ways Bleak House by Charles Dickens is very much like any other Dickens book. There are orphans, abject poverty, very wealthy people, stingy people, people with hearts of gold, light satire, mild humor, passages of purple prose and great verbosity, and unforgettable characters.

In other ways this is not a typical Dickens book. There are two different narrators, there is quite a bit of death and one of those deaths is from spontaneous combustion, there is also a murder which accounts for another of the numerous deaths, it is very tightly plotted and everything introduced into the story is accounted for by the end, and while there are cheerful scenes it is not a cheerful book. In addition, there were times when Dickens seemed like he was foreshadowing Kafka’s The Trial.

Bleak House was published in serial form between March 1852 and September 1853. Before Dickens landed on the title he tried out several others: Tom-All-Alone’s (an area of London with abandoned and falling down buildings in which the poor and homeless squatted); The Ruined House; Bleak House Academy; The East Wind (When things are not good Mr. Jarndyce always declares the wind to be in the east. This also references the east wind in London coming out of the poor quarters spreading stench and disease across the rest of the city).

We have Peter Ackroyd’s biography of Dickens on our bookshelves. It is a big fat thing and has a nice 20 pages or so on the period when Dickens was writing Bleak House. I was prompted to learn more about the book because of the murder mystery, a part of the plot that doesn’t happen until the last third or so of the book. I was surprised by the murder but the subsequent investigation by Inspector Bucket had me wanting to know what sort of influence Wilkie Collins may have had because it seemed to me lifted from one of Collins’ books. Ackroyd doesn’t say anything about Collins helping Dickens with the book or giving him advice, however, he was a frequent visitor at that time and even stayed with Dickens who was ill and living abroad when he wrote the final three or four installments of the book. Perhaps Collins had an indirect influence simply because of his presence and because the two were friends.

I did learn some other things about the book though. The character of Skimpole is based on Dickens’ friend Leigh Hunt. Skimpole is not the most likable of characters even though he is well liked in the book. He is a freeloader, always getting into debt and relying on his friends to get him out. He claims he doesn’t understand money, that he is an innocent child and one is never sure if he is telling the truth or if it is a convenient fiction Skimpole uses to get out of being responsible for anything.

When Leigh Hunt read the book he did not recognize himself in Skimpole but Hunt’s close friends did and were not pleased. When Hunt came around and finally realized what Dickens had done, he protested. The friendship cooled for awhile but it was never ruined.

Bleak House was popular with readers but not so much with critics. They declared it “dull and wearisome” and lacking in the “freedom” and “freshness” of Dickens’ previous eight novels. The book was also attacked for its “unreality,” but far from upsetting Dickens, the critique served to increase his belief that what he wrote was true and important.

The main plot of the book circles around the Chancery court and the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce. The suit is over a will and has gone on for so long that the original litigants are no longer alive. There is so much paperwork that an army of clerks is needed to carry it all in and out of court whenever the case comes up. It seems the lawyers are purposefully dragging it on forever. The case has become a joke both ins

It’s about time I get around to writing about The Warden by Anthony Trollope. I finished almost two weeks ago and just haven’t had the time to do it justice. Even having the time at the moment I’m not sure I can do it justice, but I’ll give it a go.

The Warden was published in 1864. For a Victorian novel it is quite short. For a Trollope novel, I have heard, it has a very small cast of characters. The town of Barchester where the novel is set, seems to be a quiet, bucolic sort of place. It gives the impression of being a small town but there is a rather grand cathedral there and lots of newer sorts of middle class houses.

The Warden, Mr. Harding, makes 800 a year for his very easy duties of overseeing the charity hospital that houses and feeds twelve men. The hospital was established a very long time ago by one Mr. Hiram who made his fortune off the wool industry. The Church oversees the lands and the rents and all that feed the legacy that funds the hospital and pays the warden.

Everything is hunky-dorey until the young John Bold causes a ruckus with his reformist zeal. He questions whether Hiram’s will is being carried out as he intended, whether the men living at the hospital are being cheated of income because the Church and the Warden are sucking it all up. Fair enough. But the conundrum for Bold is that he is good friends with Mr. Harding and in love with his daughter.

The novel is straightforward, pleasant, easy reading disguising a host of moral dilemmas and questions about integrity. Does Mr. Bold give up his pursuit of reform because of who the warden is? And once Mr. Harding finds out there is a question about his legitimacy can he turn a blind eye like the lawyers and the Archdeacon, who happens to be his son-in-law (married to Harding’s other daughter), tell him to? Or, having had his eyes opened must he, in order to have a clear conscious give up his wardenship? And of course, what response should the Church and church leaders have? Do they fight to retain their alleged fat-cat status or do they re-examine their values?

It is a serious story lightly told with much humor, a little sentiment, and a dash of self-mocking melodrama. Trollope also takes a few jabs at Thomas Carlyle, naming him Dr. Pessimist Anticant:

According to him nobody was true, and not only nobody, but nothing; a man could not take off his hat to a lady without telling a lie – the lady would lie again in smiling. The ruffles of the gentleman’s shirt would be fraught with deceit, and the lady’s flounces full of falsehood. Was ever anything more severe than that attack of his on chip bonnets, or the anathemas with which he endeavoured to dust the powder out of the bishops’ wigs?

Oh how this made me giggle! It would not have made sense if not for having read Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus last year with it’s philosophy of clothes.

Trollope takes a swipe at Dickens too, calling him Mr. Popular Sentiment:

Of all reformers Mr. Sentiment is the most powerful. It is incredible the number of evil practices he has put down: it is to be feared he will soon lack subjects, and that when he has made the working classes comfortable, and got bitter beer put into the proper-sized pint bottles, there will be nothing left for him to do. Mr. Sentiment is certainly a very powerful man, and perhaps not the less so that his good poor people are so very good; his hard rich people so very hard; and the genuinely honest so very honest.

Trollope prefers shades of gray. None of his characters in The Warden are wholly good or completely bad. And while they might lack somewhat for subtle nuance

Ever since I read Emerson I have been interested in reading Thomas Carlyle’s “novel” Sartor Resartus because Emerson loved it, got it published in the United States, and it influenced New England Transcendentalism. If it weren’t for the Scottish Challenge sponsored by Wuthering Expectations, I don’t when I would ever have read the book or, when I did, that I would have finished it. It is a crazy book; a philosophical treatise in the guise of satirical fiction. Here is Carlyle’s description of the book from a letter to Fraser, his publisher. Carlyle had tried to get Fraser to publish it before but was refused, and now he is trying again:

It is put together in the fashion of a Didactic Novel; but indeed properly like nothing extant. I used to characterize it briefly as a kind of “Satirical Extravaganza on Things in General”; it contains more of my opinions on Art, Politics, Religion, Heaven Earth and Air, than all the things I have yet written.

[...]

My own conjecture is that Teufelsdröckh, whenever published, will astonish most that read it, be wholly understood by very few; but to the astonishment of some will add touches of (almost the deepest) spiritual interest, with others quite the opposite feeling.

I can’t say that Carlyle’s letter does much to recommend the book, but nonetheless, Fraser published it in installments from 1833 – 1834. It did not meet with immediate success.

The title of the book means the tailor retailored which will make a little sense in a minute. The premise of the book is an unnamed British editor presenting one Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, a German Professor of Things in General, and his philosophy of clothes. Teufelsdröckh, by the way, translates as “devil’s excrement” and he is from the town of Weissnichtwo, or “Know-not-where.” The clothes in the philosophy of clothes, are, of course, actual clothes and what they say about a person as well as a metaphor of the ideas and thoughts, manners and actions we clothe ourselves in.

The unnamed editor translates the philosophy of clothes,

endeavour[ing], from the enormous, amorphous Plumpudding, more like a Scottish Haggis, which Herr Teufelsdröckh had kneaded for his fellow mortals, to pick out the choicest Plums, and present them separately on a cover of our own.

We are also given a pieced together biography of Teufelsdröckh which pretty much amounts to a spiritual journey from the Everlasting No to the Everlasting Yea with some stops in between. When Teufelsdröckh gets hot under the collar about cant, the corruption of modern life and Utilitarianism he sounds just like Carlyle when he’d get going on a rant in letters to Emerson.

Carlyle, and later Emerson, are both heavily influenced by Goethe. Sartor has numerous references to Goethe’s works, especially The Sorrows of Young Wether. The only Goethe I have had the pleasure of reading was when I took German in college and we read the fantastic poem Erlkönig (gave me poetry stomach even in my halting German), and Faust. After reading Sartor I feel like I need to read more Goethe, only this time in English as I have sadly neglected my German.

But back to Carlyle. Sartor is often compared to Tristram Shandy (another book I haven’t read) in terms of technique. It is also considered by some to be an early Existentialist text.

I worried that the book would be hard to read and I would have no idea what it was talking about. I did have to look up a few things like Sansculottism, but over all it was not hard to follow. Sometimes the book was funny; sometimes it was just flat out weird. I can’t say t

Today I welcome Elizabeth Gaskell on her Classics Circuit blog tour. The idea behind the Classics Circuit is to celebrate and encourage the reading of classic works. The Classics Circuit intends to do for dead authors what blog tours do for living authors. Anyone is welcome to join in, so if you feel inspired, don’t be shy, sign up! Sign up for the February Harlem Renaissance tour will start in a few weeks. Currently the Wilkie Collins tour is winding down and Gaskell will be out and about through the end of December. In January Edith Wharton will be making the rounds. You can find everything you need to know on the Classics Circuit blog.

Today I welcome Elizabeth Gaskell on her Classics Circuit blog tour. The idea behind the Classics Circuit is to celebrate and encourage the reading of classic works. The Classics Circuit intends to do for dead authors what blog tours do for living authors. Anyone is welcome to join in, so if you feel inspired, don’t be shy, sign up! Sign up for the February Harlem Renaissance tour will start in a few weeks. Currently the Wilkie Collins tour is winding down and Gaskell will be out and about through the end of December. In January Edith Wharton will be making the rounds. You can find everything you need to know on the Classics Circuit blog.

I’ve always wanted to read Gaskell but the works of hers that I knew about were so huge I put them off and put them off. I never thought of looking up whether she had written anything short. It turns out, she has. Lois the Witch comes in at a slim 100 pages. Published in 1859 or 1861 depending on the source, it is the only one among Gaskell’s writings set entirely in America.

Gaskell was fascinated by Americans and America. She had several American friends and correspondents. She thought of America as being a wild and mysterious place even though many of her friends lived in very civilized Boston. In spite of her interest in America she never did set foot there. This fact did not mattr when it came to writing Lois the Witch, however. Gaskell did her research.

The novella is the story of Lois Barclay, eighteen and recently orphaned. She has no family left in England. On her deathbed, Lois’s mother entreats her to go to her uncle in America. A letter is written and after her mother’s death, Lois sets sail to strange shores. But, it is Lois’s misfortune to arrive in Salem, Massachusetts a few months before the Salem witch craze strikes.

She presents herself at her uncle’s house only to find that he is on his deathbed. He leaves behind a wife, Grace Hickson, and three children. The eldest, a son named Manasseh, a girl, Faith, the same age as Lois, and a another girl, Prudence age twelve. They are a righteously Puritan family who don’t look kindly on Lois’s “Popish ways.” Lois is taken in by the Hicksons but never exactly welcome.

In spite of the lack of hospitality and family feeling, Lois does her best to fit in. She is a good, kind girl who does what she is told and contributes to the running of the household. No one can say a bad word against her until accusations of witchcraft break out.

I don’t know what Gaskell’s sources on the Salem witch trials were, but her accounting of the 1692 trials is accurate. Except for Cotton Mather she changes the names of those involved and takes some liberty with the story but adheres closely to the events.

The only thing I didn’t like about the story is the narrator breaking into it from time to time. She does so as a way to move the story forward through narrative summary instead of through writing out the events. The narrator also breaks in to remind and explain to the reader that these events happened long ago and that even England accused and killed people for being witches at one time. It seemed when she did this that she was also defending America from being labeled superstitious and backwards. Aside from these narrative interruptions, the story is enjoyable and, I think, a good, and short, introduction to Gaskell.

Information on Gaskell and America comes from an article entitled “Alligators infesting the stream: Elizabeth Gaskell and the USA&rdq

I discovered a rather snobby essay by Edith Wharton today as I was looking her up in the library catalog. Wharton has nothing to do with law that I know of and law students weren’t clamoring to know about her. It was a down moment and I thought, I wonder what Wharton books are available? So I looked her up just because and found an essay called The Vice of Reading, published in the North American Review, October, 1903.

In the essay Wharton differentiates between two kinds of readers, the mechanical reader and the intuitive reader. The intuitive reader is the reader who was “born to read,” the good reader, the one who understands books and learns from books, the one for whom “reading forms a continuous undercurrent to all his other occupations.” For the born reader, reading is not a vice. Wharton has her beef with the mechanical reader.

Mechanical readers are the ones that read the books that everyone else is reading. They are also the ones who read because they think they ought to and they deliberately undertake reading for the purpose of being able to pass opinions and display how culturally with it they are. These are poor readers because they don’t know how to read and often don’t understand what they read. If these readers just stuck to reading the mediocre trash that they seem to like so well, then everything would be fine. But they don’t and because they don’t they pose a menace to Literature.

Mechanical readers are like tourists “who drive from one ’sight’ to another without looking at anything that is not set down in Baedeker.” The delights of allusions and turns of phrase are lost on them. For these readers

books once read are not like growing things that strike root and intertwine branches, but like fossils ticketed and put away in the drawers of a geologist’s cabinet; or rather, like prisoners condemned to lifelong solitary confinement. In such a mind the books never talk to each other.

The menace mechanical readers pose to literature is fourfold:

- Because mechanical readers are most satisfied with mediocre writing, they facilitate the careers of mediocre authors. Not only does this allow people who shouldn’t be writing to write, but it keeps those who do have creative talent from being encouraged to reach their full potential.

- “Secondly, by his passion for “popular” renderings of abstruse and difficult subjects, by confounding the hastiest rechauffe of scientific truisms with the slowly-matured conceptions of the original thinker, he retards true culture and lessens the possible amount of really abiding work.”

- The mechanical reader has the habit of confusing moral and intellectual judgments. He cannot separate and grasp the difference between the portrayal of life and incidents in the book from the “author’s sense of their significance.”

- The mechanical reader’s “demand for peptonized literature” has created the mechanical critic who simply summarizes the plot and calls it a day instead of doing any kind of thoughtful analysis.

Wharton’s snobbery in the essay is both appalling and amusing. Perhaps I am mistaken, but I get the sense that she doesn’t believe that poor readers can, with practice become good readers. You can either read or you can’t and if you can’t then you shouldn’t. Not very democratic.

Read the essay when you have a free 15-20 minutes. I’m pretty sure Wharton meant every word, but part of me wonders if she isn’t writing tongue in cheek. Your thoughts and opinions welcome.

Posted in Essays, Nineteenth Century

You know, I’ve been contemplating adding a Jane Austen book to my binge pile and have been waffling between Persuasion which I have read twice and loved, or Mansfield Park which I have read once and, to the dismay of many particularly my graduate seminar professor, did not like.

My dislike for it was made worse because I had to write my seminar paper on the book. The professor didn’t want us all writing about the same book and so no more than two people were allowed to write about each one. She passed around a signup list. We always sat in a circle and on the evening the list went around I was sitting on the immediate right of the professor. Guess which way the list went? By the time it got to me the only spot left was for Mansfield Park.

Fortunately, I don’t still have the paper because it would probably be an embarrassment. But I was so unhappy about having to write about the book that my dislike for it flared larger than was warranted and I made a rousing argument for how horribly flawed the book was, focusing mainly on the character of Fanny and the way the book ends. I managed to dig up a few good articles to support my argument so my professor begrudgingly gave me an A-.

Time has erased my memory of the details of my dislike and I have for many years felt as though I have done the book and Austen a disservice in some way. Which brings me to why I have been thinking about reading the book again.

Today my decision to include the book in my binge pile was sealed when I came across this article about a Jane Austen exhibit, The Divine Jane: Reflections on Austen at the Morgan Library and Museum.

There was a short documentary film made especially for the exhibit, A Woman’s Wit: Jane Austen’s Life and Legacy. It’s fifteen minutes long and well worth the time. It features interviews with writers, scholars and actors all reflecting on Austen and her art and what makes it so great.

I was still waffling between choosing Persuasion or Mansfield Park when I began watching the video and it was Colm Toibin who helped me decide. At one point he suggests that taking Mansfield Park to bed is more satisfying in many ways than taking a person to bed.

I have no intention of slighting my dear husband, but it does seem like a good time to give Fanny a second chance. I’ll just have to be sure she doesn’t come to bed with me; I wouldn’t want my Bookman to get jealous.

Posted in Books, Jane Austen, Nineteenth Century