We celebrate the 50th anniversary of the holiday classic with a gallery of rare artwork from the film.

The post ‘How The Grinch Stole Christmas!’ is 50 Years Old Today—And It’s Still Great appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

We celebrate the 50th anniversary of the holiday classic with a gallery of rare artwork from the film.

The post ‘How The Grinch Stole Christmas!’ is 50 Years Old Today—And It’s Still Great appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Can Warner Bros. reboot Pepe Le Pew for modern audiences?

The post Comic-Con 2016: Warner Bros. Developing Animated Pepe Le Pew Feature appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Figuring out how to make the characters in "The Angry Birds Movie" look simple was a big challenge for Sony Imageworks.

The post A Big Challenge: Making Characters in ‘Angry Birds Movie’ Look Simple appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

The creator of "Hamilton" reveals an unlikely source of inspiration.

The post ‘Hamilton’ Creator Lin-Manuel Miranda Learned About the Creative Process From The Best appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Dante calls this unproduced film the "heartbreaker" of his filmmaking career.

The post Joe Dante Talks About ‘Termite Terrace,’ The Film He Tried To Make About Warner Bros. Animators appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Sixty years ago on this day — December 31, 1955 — a short masterpiece was released into movie theaters: Chuck Jones’ One Froggy Evening. No one said anything at the time because hardly anyone ever said anything about animation at the time.

Eventually the short gained its due recognition. “The Citizen Kane of animated shorts,” Steven Spielberg once called it, and even if Spielberg had said nothing, this wordless wonder would still qualify as one of the finest of Jones’ couple of hundred Warner Bros. shorts.

Before we proceed any further though, let’s watch the film:

Let me admit: as many times as I’ve watched this film, I still cannot understand how it was made. Technically, I get it, but there’s something else going on that is impenetrable. Every member of Jones’ team is operating at the peak of their craft, a level achieved through decades of toil and refinement, yet their collaboration appears so seamless and absolute that it does not seem possible for the cartoon to have been created by mere mortals. As the skies above us and the ground below us, this cartoon is a perfectly formed natural wonder that cannot be improved upon.

The credit is due to just a couple handfuls of key individuals: Michael Maltese’s story structure reveals just enough but not all of the mystery; Abe Levitow, Richard Thompson, Ken Harris, and Ben Washam bring the characters to life through perfectly timed and funny animation (it’s funny because it’s perfectly timed); the layouts of Bob Gribbroek and background paintings of Phil DeGuard drop us into the middle of a believable mid-20th century American metropolis. And let’s not forget the musical stylings of Milt Franklyn, the sound effects of Treg Brown, and certainly not the voice of Michigan J. Frog himself, Bill Roberts.

And consider this: Jones’s crew made a new short every three weeks or so. These guys didn’t labor over this film for years, and they certainly didn’t have time to reflect or be precious about it. They simply churned it out, as they did countless others, over and over again. Lather, rinse, repeat, and eventually retire.

But it is director Jones himself who reminds us why he is considered one of animation’s greats. The presence of Jones, who created more layout drawings per film than almost any other Golden Age theatrical short director, can be felt in every expression and pose of One Froggy Evening. Jones doesn’t rely on pre-existing stock poses or expressions. He is a cartoonist who is a master of his universe, and he effortlessly creates custom poses and expressions for each and every scene, in his inimitable style that can only be described as Jonesian.

Jones’ advantage is that he has something that most comedy animation directors, then or now, don’t have, which is an obsession for detail. When he couldn’t find the proper ragtime tune for his singing frog, he wrote his own from scratch with the help of Maltese, resulting in “The Michigan Rag.” The song sounds so authentic that to this day people wonder which songs in the film were pre-existing and which were created specifically for the film (this site explains it all).

His gift for observation extended to his amphibian star. As a frog owner myself, I’m routinely annoyed when animators don’t take the time to get frogs right. When a frog swallows his food, his eyes sink deep into his head. Few animators seem to notice this. But there is no such laziness in Jones’s work. “I remembered from when I was a kid,” Chuck Jones once explained. “Any boy that’s ever picked up a frog knows how the body sits and the limbs hang down. So we had to be certain, in those first few seconds on the screen, that when [Michigan] appeared he looked like a frog. Even that his eyes blinked upward.”

Perhaps audiences didn’t notice every single directorial choice that Jones made during the course of the production. Eyes blinking upward certainly won’t make or break any cartoon. But those hundreds of directorial choices in an animated film eventually add up. And audiences always notice one thing: does the director care? Jones cared. He obsessed. And in this rare instance, he made all the right choices, resulting in a perfect cartoon gem.

Frankly, I’m content with the fact that I’ll never understand how he and his crew made it.

The post An Appreciation of Chuck Jones’ ‘One Froggy Evening’ On Its 60th Birthday appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

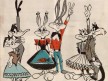

Add a CommentNow 75, Bugs Bunny remains a towering influence. We look at some of his greatest hits.

Add a CommentThe filmmaking essay series "Every Frame A Painting" takes a trip into the wondrous, disciplined mind of legendary animation director Chuck Jones.

Add a Comment"Inside Out" production designer Ralph Eggleston and historian John Canemaker will introduce some of the screenings.

Add a CommentCut through the clutter with our handy guide to the must-see animation events happening in San Diego this year.

Add a CommentThese rare videos document the presentation of the animated short Oscar from 1949 through 2013.

Add a CommentIn this 1980 tribute to legendary animation director Tex Avery, fellow legendary director Chuck Jones shared six lessons that he learned about comedy from working with Avery in the 1930s. The advice remains essential to animation director working today.

Add a CommentThe exhibit “Chuck Jones: Doodles of a Genius” has opened at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California. We've previously written about the show, which features random non-production doodles by the great Golden Age theatrical short director, and now we have a preview of some of those doodles on display thanks to the official Chuck Jones Tumblr.

Add a CommentWhat's the only thing better than a Chuck Jones museum show? How about TWO Chuck Jones museum shows?

Add a Comment

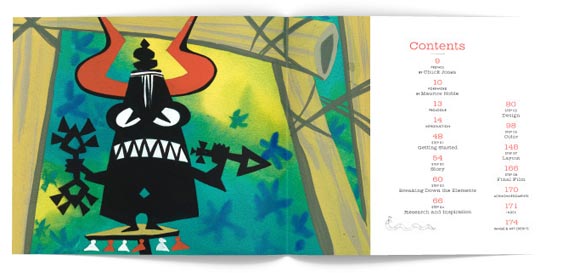

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and

The Zen of Animation Design

By Tod Polson, based on the notes of Maurice Noble

(Chronicle Books, 176 pages, $40, pre-order for $26.50 on Amazon)

By the modest standards of celebrity in the animation world, Maurice Noble is already a rockstar. Few Golden Age layout artists and background designers, with the exception of Eyvind Earle, Mary Blair, and possibly Jules Engel, command Noble’s name recognition. Maurice’s fame is primarily attributable to his long-term association with Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones.

Noble’s collaborations with Jones include such classics as Robin Hood Daffy, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, What’s Opera, Doc?, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, The Dot and the Line and the long-running Wile E. Coyote/Roadrunner series. Thanks to that beloved resume, Noble has been spared the ignoble anonymity of so many other classic animation artists.

With such standing in the animation world, and even an entire book-length biography already devoted to his life, one could reasonably expect that everything that could be said about Noble has already been said. Tod Polson’s The Noble Approach proves that that’s not the case. Polson has put together an irresistible package that fuses biography and art instruction, each of its page filled with invaluable insights and incredible artwork, much of it never-before-published.

Polson is one of the Noble Boys, the informal name given to a group of men (and women) whom Noble trained throughout the 1990s at studios like Chuck Jones Film Productions, Turner Feature Animation and his own company, Noble Tales. The Noble Boys have gone on to big things in the animation industry: Ricky Nierva was the production designer of Pixar’s Up and Monsters University; Don Hall directed Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and is writing and directing the upcoming Big Hero 6; Jorge Gutierrez co-created the Nick series El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera and is directing Reel FX’s 2014 feature Book of Life.

Some of the Noble Boys encouraged Maurice to write down his thoughts about design and layout for an eventual book. Polson has adeptly compiled and edited those notes for this book, and has combined them with the remembrances of the other Noble Boys about their interactions with Maurice and lessons learned from him, as well as archival interviews with Noble and original commentary from artists like Susan Goldberg and Michael Giaimo.

Polson devotes thirty-four pages of the book to providing a biography of Noble that follows his path which began professionally at Disney on films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Bambi. In spite of its brevity, this biographical section manages to be more revealing and historically well-rounded than the disappointing 2008 book Stepping into the Picture: Cartoon Designer Maurice Noble by Robert J. McKinnon. That well-intentioned book missed the mark—badly. It was understandable that McKinnon’s layperson understanding of the animation process prevented him from providing the kind of process detail that is in Polson’s new book, but his sins of omission made it a letdown as personal biography, too.

Basic and vital details about Noble’s personal and professional relationships that were omitted in that earlier biography are thankfully included in Polson’s book. For example, we learn hat Mary Blair and Maurice Noble were not only classmates at Chouinard Art Institute, but also a romantic couple. That’s a revealing historical tidbit considering that Noble’s giddy use of color is second in animation only to Mary Blair. Polson clearly expresses Noble’s unflattering thoughts about Sleeping Beauty production designer Eyvind Earle, with whom he worked during the production of the industrial film Rhapsody of Steel, whereas the earlier biography only vaguely acknowledged that Noble “may have had some difficulty working with Earle.” Polson also discusses Noble’s more-important-than-acknowledged role on Chuck Jones’ Oscar-winning short The Dot and the Line, an issue that was left untouched in the earlier book.

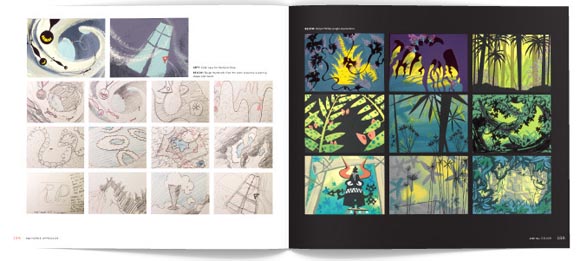

For all its historical value, the real meat of the Noble Approach follows the biography. In these subsequent sections, we learn Noble’s artistic process step-by-step from the start of a film to its completion. Chapters are devoted to starting a film, story, breaking down the elements, research, design, color, layout, and an oddly ineffectual and anticlimatic two-page chapter devoted to the finished film.

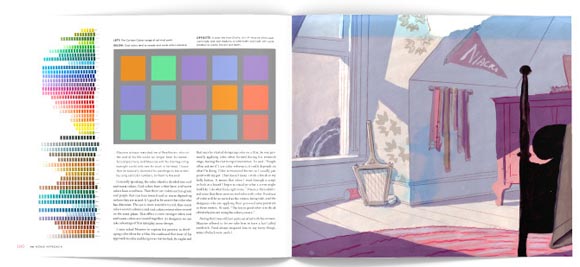

The material covered in these chapters will undoubtedly be familiar to anyone with an art background—values, contrast, simplifying elements, visual hierarchy, compositional grids—but the examples of Maurice’s own work gives us a fresh entry point into these topics. The section on color is particularly fantastic. Color is one of the hardest elements to get right in animated film, and Maurice knew how to walk the thin line between playful and tacky. Polson does a superb job of explaining how Maurice managed to do this by doing a deep analysis of his color palettes.

The section on color, for all its strengths, also represents one of the parts of the book that I wish the author had expanded his scope. Polson makes clear from the outset that this is “Maurice’s book,” but I can’t help but think our appreciation for Noble would have been enhanced further by offering some discussion of his contemporaries at Warner Bros., like layout artist Hawley Pratt and background painter Paul Julian. Contrasting the color theories of Julian, who was the studio’s true master of color in my opinion, would have been an enlightening sidetrip.

A lot of the best information the book isn’t technical, but rather practical advice and the wisdom of experience. This is true of Noble’s thoughts on selling an idea:

To be a successful designer, being able to sell a good idea is just as important as coming up with the idea itself. It’s hard to sell something simply because you think it feels right. You have to be able to logically discuss why it feels right.

—and his thoughts on why the production methods of yesteryear produced better cartoons:

There is more talent working in the industry now than ever before, but sadly the vast majority won’t have the opportunity to work on really good creative stories. The problem isn’t always the type of stories being told; it’s more in the way these stories are being told and developed. There is no room for visual exploration. There is no time for thought and craftsmanship. There isn’t the chance for crews to build trust and synergy.

The production design tips that he offers are applicable to artists today, even if the tools of the trade have changed:

I suggest putting all your research materials away once you start designing and never refer to them again. This may prove difficult at first. But I’ve found that if you are tied too closely to your reference, your designs will tend to look stiff. You will miss out on many fun design opportunities.

or…

Starting rough and not getting specific too early will allow you to keep your design ideas flexible…The more ideas and work you have, the more design possibilities you will have to choose from.

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design ranks among the most unique and delightful animation books in recent memory. It goes without saying that the book’s mix of technical tips and advice makes it a must-buy title for professional artists and students, but it should also appeal to fans of classic of animation who will surely gain a renewed appreciation for the Chuck Jones canon. The book will be released on October 1st. For those who are still in need of convincing, the book’s official blog gives a nice sense of the book’s content.

In their new episode, the podcast 99% Invisible profiles legendary layout artist Maurice Noble. Noble made significant contributions to Disney films like Dumbo and Bambi, but he is better known for his layout and design work with Chuck Jones on memorable Warner Bros. shorts like Duck Amuck, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, Ali Baba Bunny, What’s Opera, Doc?, and the Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote series.

That’s why it may be surprising for many readers to learn in this podcast about the personality battles between Noble and Jones, and how the two men weren’t particularly fond of one another despite their frequent collaborations. The subjects who were interviewed for the podcast are reliable authorities on Noble: his biographer Bob McKinnon; Tod Polson whose upcoming book about Noble’s techniques will be a must-own; and Pixar artist Scott Morse, who worked with Noble early in his career.

(Thanks, Bob Flynn)

Add a Comment

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Chris Columbus’ comedy Mrs. Doubtfire. In the opening of the film, Robin Williams plays a voice-over artist who is recording lines for a cartoon that has already been made. (Yes, that’s out of order for a standard cartoon production, but for entertainment’s sake, we’ll let it slide).

The cartoon was supervised by legendary Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones, and animated by a small team of A-list animators that included legends like Bill Littlejohn and Tom Ray, and younger animators like Eric Goldberg. Coincidentally, Goldberg was also animating to the voice of Robin Williams for another animated project around the same period—the Genie in Aladdin.

In the film, we see barely a minute’s worth of animation of the two main characters—Pudgy Parakeet and Grunge the Cat. But in reality, Chuck Jones and his crew animated five minutes of material. This was never publicly shown until it was included several years afterward as a bonus feature on the Mrs. Doubtfire DVD.

While the cartoon doesn’t break any new ground in terms of execution or gags, and doesn’t even have a proper ending (it ends with a repeating cycle of Pudgy enjoying a cigarette for thirty seconds), the short has its moments. Williams voices all three characters, and it’s enjoyable listening to his vocal delivery. The animation, being much more fluid than Jones’ typical output of the period, is lively and filled with the energy of his classic cartoons from the mid-1950s.

The story doesn’t end there, though. Apparently, Chuck Jones wasn’t too keen on the backgrounds, feeling that they were overly detailed. So Jones had the cartoon completely reshot with new backgrounds that reflected a more subdued graphic style. As an added bonus, here’s the alternate version:

And just for good measure, here is a two-minute pencil test:

Add a Comment

Chuck Jones is one of the marquee names of American animation history. He created characters such as Pepe le Pew, Marvin Martian, Gossamer, Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, and directed classic shorts like Rabbit Seasoning, Duck Amuck, Feed the Kitty, The Dover Boys, One Froggy Evening, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century and What’s Opera, Doc?, to name just a few. A lesser known fact about Jones is that during the 1950s he and his wife Dorothy (nickname: Dottie) were avid participants of the Southern California Western square dancing craze, a style of dance explained in this video:

Chuck Jones is one of the marquee names of American animation history. He created characters such as Pepe le Pew, Marvin Martian, Gossamer, Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, and directed classic shorts like Rabbit Seasoning, Duck Amuck, Feed the Kitty, The Dover Boys, One Froggy Evening, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century and What’s Opera, Doc?, to name just a few. A lesser known fact about Jones is that during the 1950s he and his wife Dorothy (nickname: Dottie) were avid participants of the Southern California Western square dancing craze, a style of dance explained in this video:

Jones never spoke of his love for square dancing in either of his biographies: Chuck Amuck or Chuck Reducks. His appreciation for the dance never manifested itself in the films he made either. In fact, the quintessential Warner Bros. square dance cartoon, Hillbilly Hare, was directed by Jones’ colleague, Robert McKimson. Jones’ enthusiasm for square dancing was well known around the studio, however. He organized lunchtime dances, and claimed that the other directors, like McKimson and Friz Freleng, as well as producer Eddie Selzer, became fascinated with the dance as well.

Throughout the 1950s, Chuck contributed magazine covers and a regular column to a Southern California magazine called Sets in Order. Within the past year, the University of Denver Digital Archive has added a PDF archive of Sets in Order. (Go HERE for a more clearly indexed list of back issues). In the gallery below, I’ve compiled all of Chuck’s covers, a couple illustrated articles he did, and one of his columns which was especially animation related. Should you wish to dig through the archives, there are dozens of other “Chuck’s Notebook” columns within the 1950s and early-’60s issues. They’re esoteric and often obtuse, but are decorated with Chuck’s spot illustrations and provide some unique insights into his personality.

Throughout the 1950s, Chuck contributed magazine covers and a regular column to a Southern California magazine called Sets in Order. Within the past year, the University of Denver Digital Archive has added a PDF archive of Sets in Order. (Go HERE for a more clearly indexed list of back issues). In the gallery below, I’ve compiled all of Chuck’s covers, a couple illustrated articles he did, and one of his columns which was especially animation related. Should you wish to dig through the archives, there are dozens of other “Chuck’s Notebook” columns within the 1950s and early-’60s issues. They’re esoteric and often obtuse, but are decorated with Chuck’s spot illustrations and provide some unique insights into his personality.

There are lots of hidden goodies in the columns that Jones wrote, and now that they are so readily accessible, they will hopefully be scrutinized more closely by historians. Animator and historian Greg Duffell introduced me to these drawings when he did an article about them in my ‘zine Animation Blast. In that piece, Greg pointed out astutely how some of Chuck’s drawings in the magazine foreshadowed the designs of characters who later appeared in films like The Phantom Tollbooth, Deduce You Say, Rocket-bye Baby and I was a Teenage Thumb. Whether you recognize the references or not, the drawings that Jones created for Sets in Order stand on their own and can be appreciated today as exquisite examples of mid-century cartooning.

All the material in here was drawn by Chuck Jones for Sets in Order which is copyright Bob Osgood.

Add a Comment

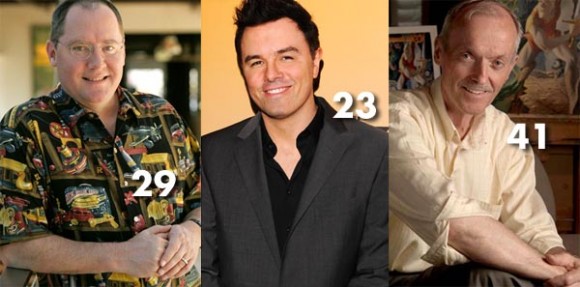

“Animation is a young man’s game,” Chuck Jones once said. There’s no question that animation is a labor-intensive art that requires mass quantities of energy and time. While it’s true that the majority of animation directors have directed a film by the age of 30, there are also a number of well known directors who started their careers later.

Directors like Pete Docter, John Kricfalusi and Bill Plympton didn’t begin directing films until they were in their 30s. Don Bluth, Winsor McCay and Frederic Back were late bloomers who embarked on directorial careers while in their 40s. Pioneering animator Emile Cohl didn’t make his first animated film, Fantasmagorie (1908), until he was 51 years old. Of course, that wasn’t just Cohl’s first film, but it is also considered by most historians to be the first true animated cartoon that anyone ever made.

Here is a cross-selection of 30 animation directors, past and present, and the age they were when their first professional film was released to the public.

If you want something done right, you have to do it yourself.

Walt Kelly had had a regrettable experience making The Pogo Special Birthday Special (1969) with Chuck Jones.

“How did you ever okay Chuck’s Pogo story?,” Ward Kimball asked Walt Kelly shortly after the special aired on TV. “I didn’t, for Godsake!,” Kelly cried out. “The son of a bitch changed it after our last meeting. That’s not the way I wrote it. He took all the sharpness out of it and put in that sweet, saccharine stuff that Chuck Jones always thinks is Disney, but isn’t.” Kimball, who was dining with Kelly at the Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood, pressed further. “Who okayed giving the little skunk girl a humanized face?” he asked. Kelly was so angry he couldn’t answer. His face turned red, and he bellowed to the waiter, “Bring me another bourbon!” In Kimball’s words, Kelly wanted “to kill—if not sue—Chuck.”

Shortly after that debacle, Walt Kelly took matters into his own hands and decided to personally animate his popular Pogo characters. With the help of his wife Selby Daley, he planned on creating a fully-animated half-hour special for television, with the characters expressing a strong stance on taking care of the environment. But due to his ill-health, he was able to complete only thirteen minutes of We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us, which you see below.

The finished portions are absolutely charming and beautifully crafted. Much like his character P.T. Bridgeport, Kelly is a real showman here. Although he hadn’t animated since Dumbo thirty years prior, his animation skills are still top-notch. While the animation can be a bit choppy at times (mostly keys and some breakdowns with no in-betweens), his drawings are solid and appealing with some real flourishes of fluid animation throughout.

The color, though muddy in the existing prints, also appears to be as vibrant as his Sunday pages, and the backgrounds are as intricately detailed as his splash panels, if not more so. And the voices, humorously performed by Kelly himself, fit the tone and mood of his characters.

Besides Winsor McCay, I can’t think of any other mainstream comic artist who animated their comics to such a painstaking degree. While many comic strips have been adapted for film and television before and since, none of them have met or surpassed the charm and quality of the original artist’s work. Here, the animator and the creator is one and the same, and the drawings are pure, unfiltered and straight from the artist’s hand.

Add a Comment