new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Aristotle, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 23 of 23

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Aristotle in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: John Priest,

on 10/1/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

Islam,

Plato,

Aristotle,

sufism,

*Featured,

POTM,

Arts & Humanities,

Philosopher of the Month,

philosopherotm,

Islamic Culture,

islamic ethics,

islamic philosophy,

al-kindi,

islamic authors,

islamic philosophers,

islamic thinkers,

islamic thought,

kindian philosophy,

metaphsyics,

Neoplatonism,

Add a tag

Known as the “first philosopher of the Arabs,” al-Kindī was one of the most important mathematicians, physicians, astronomers and philosophers of his time. He composed hundreds of treatises, using many of the tools of Greek philosophy to address themes in Islamic thought.

The post Philosopher of the month: al-Kindī appeared first on OUPblog.

By: John Priest,

on 9/19/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

quiz,

ethics,

classics,

Philosophy,

ancient greece,

Aristotle,

Greece,

*Featured,

POTM,

classical greece,

Quizzes & Polls,

history of philosophy,

western philosophy,

Arts & Humanities,

ancient philosophy,

Philosophy Quiz,

Philosopher of the Month,

philosopherotm,

potm quiz,

philosopher of the month quiz,

Classical Philosophy,

ancient philosophers,

Western philosophers,

Add a tag

Among the world’s most widely studied thinkers, Aristotle established systematic logic and helped to progress scientific investigation in fields as diverse as biology and political theory. But how much do you really know about this ancient philosopher?

The post How well do you know Aristotle? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Cassandra Gill,

on 9/5/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

back to school,

ancient greece,

Plato,

Aristotle,

Greece,

Socrates,

archimedes,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

schoolchildren,

Online products,

Arts & Humanities,

Hippocrates,

oxford classical dictionary,

oxford classical dictionary online,

classical Greek education,

Greek education system,

School of Athens,

History,

Add a tag

It’s back-to-school time again – time for getting back into the swing of things and adapting to busy schedules. Summer vacation is over, and it’s back to structured days of homework and exam prep. These rigid fall schedules have probably been the norm for you ever since you were in kindergarten.

The post How much do you know about ancient Greek education? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: John Priest,

on 9/4/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

timeline,

ancient greece,

Aristotle,

Timelines,

*Featured,

ancient greek,

POTM,

classical greece,

history of philosophy,

western philosophy,

Arts & Humanities,

ancient philosophy,

Philosopher of the Month,

philosopherotm,

philosophy timeline,

ancient greek philosophy,

classical greek philosophy,

Classical Philosophy,

Add a tag

Among the world’s most widely studied thinkers, Aristotle established systematic logic and helped to progress scientific investigation in fields as diverse as biology and political theory. His thought became dominant during the medieval period in both the Islamic and the Christian worlds, and has continued to play an important role in fields such as philosophical psychology, aesthetics, and rhetoric.

The post Philosopher of the month: Aristotle appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 7/28/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Aristotle,

back pain,

backache,

scientific method,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

genomics,

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

The Double Helix with Dawn Field,

chiropractor,

physical therapist,

The New Age of Genomics,

yoga instructor,

Add a tag

Do you have back pain? Statistics show you likely do. Or you have had it in the past or will in the future. Back pain can be a million different things, and you can get it an equal number of ways. Until you've suffered it, you don't realise how disruptive it can be. Trying to fix back pain is a superb way to make people understand the power of scientific method and how to use it.

The post Scientific method and back pain appeared first on OUPblog.

By: John Priest,

on 2/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

timeline,

ancient greece,

Plato,

Aristotle,

the republic,

Socrates,

Athens,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

christian theology,

ancient philosophy,

ancient athens,

Philosopher of the Month,

philosopherotm,

platonism,

academy of athens,

philosophy facts,

platonic,

platonic dialogues,

Add a tag

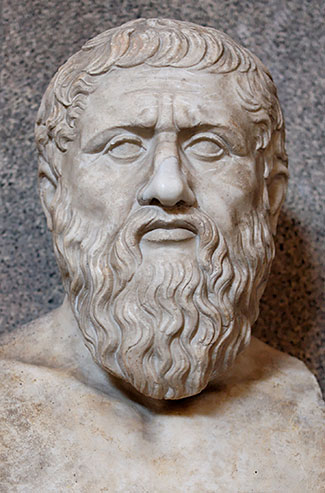

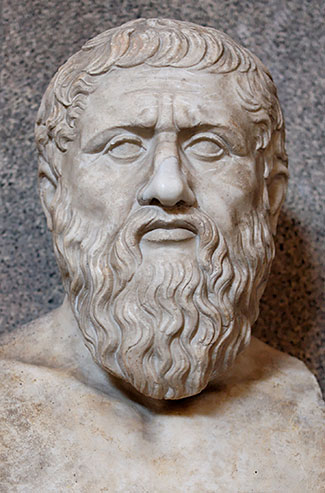

The OUP Philosophy team have selected Plato (c. 429–c.347 BC) as their February Philosopher of the Month. The best known and most widely studied of all the ancient Greek philosophers, Plato laid the groundwork for Western philosophy and Christian theology. Plato was most likely born in Athens, to Ariston and Perictione, a noble, politically active family.

The post Philosopher of the month: Plato appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Samantha Zimbler,

on 2/3/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

classics,

Geography,

Strabo,

ancient greece,

Aristotle,

ancient history,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

Eratosthenes,

Online products,

oxford online,

oxford classical dictionary,

oxford classical dictionary online,

circumference of earth,

Krates of Mallos,

Strabo of Amaseia,

Pythagorean theory,

Krates,

Add a tag

Imagine how the world appeared to the ancient Greeks and Romans: there were no aerial photographs (or photographs of any sort), maps were limited and inaccurate, and travel was only by foot, beast of burden, or ship. Traveling more than a few miles from home meant entering an unfamiliar and perhaps dangerous world.

The post Geography in the ancient world appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 7/30/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

UKpophistory,

Earth & Life Sciences,

biology,

zoology,

Aristotle,

eighteenth-century,

animal vegetable mineral,

life sciences,

victorian britain,

Linnaeus,

Mrs Gren,

Susannah Gibson,

the natural world,

life,

school,

Education,

nature,

science,

Books,

History,

British,

Add a tag

Did you learn about Mrs Gren at school? She was a useful person to know when you wanted to remember that Movement, Respiration, Sensation, Growth, Reproduction, Excretion, and Nutrition were the defining signs of life. But did you ever wonder how accurate this classroom mnemonic really is, or where it comes from?

The post What is life? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 2/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Philosophy,

truth,

Plato,

Aristotle,

right,

commuting,

twitter chat,

Wrong,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Arts & Humanities,

#tetralogue,

philosophical conversation,

Timothy Williamson,

trains of thought,

philosophical conversartion,

Alfred Tarski,

Samarkand,

Uzbekistan,

Add a tag

Tetralogue by Timothy Williamson is a philosophy book for the commuter age. In a tradition going back to Plato, Timothy Williamson uses a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth and falsity, knowledge and belief. Four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train and start talking about what they believe. Their conversation varies from cool logical reasoning to heated personal confrontation. Each starts off convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in. During February, we will be posting a series of extracts that cover the viewpoints of all four characters in Tetralogue. What follows is an extract exploring Roxanna’s perspective.

Roxanna is a heartless logician with an exotic background. She would much rather be right than be liked, and as a result she argues mercilessly with the other characters.

Roxana: You appear not to know much about logic.

Sarah: What did you say?

Roxana: I said that you appear not to know much about logic.

Sarah: And you appear not to know much about manners.

Roxana: If you want to understand truth and falsity, logic will be more useful than manners. Do any of you remember what Aristotle said about truth and falsity?

Bob: Sorry, I know nothing about Aristotle.

Zac: It’s on the tip of my tongue.

Sarah: Aristotelian science is two thousand years out of date.

Roxana: None of you knows. Aristotle said ‘To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true’. Those elementary principles are fundamental to the logic of truth. They remain central in contemporary research. They were endorsed by the greatest contributor to the logic of truth, the modern Polish logician Alfred Tarski.

Bob: Never heard of him. I’m sure Aristotle’s saying is very wise; I wish I knew what it meant.

Roxana: I see that I will have to begin right at the very beginning with these three.

Sarah: We can manage quite well without a lecture from you, thank you very much.

Roxana: It is quite obvious that you can’t.

Roxana: It is quite obvious that you can’t.

Zac: I’m afraid I didn’t catch your name.

Roxana: Of course you didn’t. I didn’t say it.

Zac: May I ask what it is?

Roxana: You may, but it is irrelevant.

Bob: Well, don’t keep us all in suspense. What is it?

Roxana: It is ‘Roxana’.

Zac: Nice name, Roxana. Mine is ‘Zac’, by the way.

Bob: I hope our conversation wasn’t annoying you.

Roxana: Its lack of intellectual discipline was only slightly irritating.

Bob: Sorry, we got carried away. Just to complete the introductions, I’m Bob, and this is Sarah.

Roxana: That is enough time on trivialities. I will explain the error in what the woman called ‘Sarah’ said.

Sarah: Call me ‘Sarah’, not ‘the woman called “Sarah” ’, if you please.

Bob: ‘Sarah’ is shorter.

Sarah: Not only that. We’ve been introduced. It’s rude to describe me at arm’s length, as though we weren’t acquainted.

Roxana: If we must be on first name terms, so be it. Do not expect them to stop me from explaining your error. First, I will illustrate Aristotle’s observation about truth and falsity with an example so simple that even you should all be capable of understanding it. I will make an assertion.

Bob: Here goes.

Roxana: Do not interrupt.

Bob: I was always the one talking at the back of the class.

Zac: Don’t worry about Bob, Roxana. We’d all love to hear your assertion. Silence, please, everyone.

Roxana: Samarkand is in Uzbekistan.

Sarah: Is that it?

Roxana: That was the assertion.

Bob: So that’s where Samarkand is. I always wondered.

Roxana: Concentrate on the logic, not the geography. In making that assertion about Samarkand, I speak truly if, and only if, Samarkand is in Uzbekistan. I speak falsely if, and only if, Samarkand is not in Uzbekistan.

Zac: Is that all, Roxana?

Roxana: It is enough.

Bob: I think I see. Truth is telling it like it is. Falsity is telling it like it isn’t. Is that what Aristotle meant?

Roxana: That paraphrase is acceptable for the present.

Have you got something you want to say to Roxanna? Do you agree or disagree with her? Tetralogue author Timothy Williamson will be getting into character and answering questions from Roxanna’s perspective via @TetralogueBook on Friday 20th March from 2-3pm GMT. Tweet your questions to him and wait for Roxanna’s response!

The post Trains of thought: Roxanna appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 11/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

reading list,

herodotus,

sophocles,

OWC,

Plato,

euripides,

Iliad,

Aristotle,

Oxford World's Classics,

Homer,

Plutarch,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

plato's republic,

Arts & Humanities,

Antigone,

Apollonius,

Electra,

Judith Luna,

Oedipus the King,

The Trojan Women and Other Plays,

Add a tag

This selection of ancient Greek literature includes philosophy, poetry, drama, and history. It introduces some of the great classical thinkers, whose ideas have had a profound influence on Western civilization.

Jason and the Golden Fleece by Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius’ Argonautica is the dramatic story of Jason’s voyage in the Argo in search of the Golden Fleece, and how he wins the aid of the Colchian princess and sorceress Medea, as well as her love. Written in the third century BC, it was influential on the Latin poets Catullus and Ovid, as well as on Virgil’s Aeneid.

Poetics by Aristotle

This short treatise has been described as the most influential book on poetry ever written. It is a very readable consideration of why art matters which also contains practical advice for poets and playwrights that is still followed today.

The Trojan Women and Other Plays by Euripides

One of the greatest Greek tragedians, Euripides wrote at least eighty plays, of which seventeen survive complete. The universality of his themes means that his plays continue to be performed and adapted all over the world. In this volume three great war plays, The Trojan Women, Hecuba, and Andromache, explore suffering and the endurance of the female spirit in the aftermath of bloody conflict.

The Histories by Herodotus

Herodotus was called “the father of history” by Cicero because the scale on which he wrote had never been attempted before. His history of the Persian Wars is an astonishing achievement, and is not only a fascinating history of events but is full of digression and entertaining anecdote. It also provokes very interesting questions about historiography.

The Iliad by Homer

Homer’s two great epic poems, the Odyssey and the Iliad, have created stories that have enthralled readers for thousands of year. The Iliad describes a tragic episode during the siege of Troy, sparked by a quarrel between the leader of the Greek army and its mightiest warrior, Achilles; Achilles’ anger and the death of the Trojan hero Hector play out beneath the watchful gaze of the gods.

Republic by Plato

Plato’s dialogue presents Socrates and other philosophers discussing what makes the ideal community. It is essentially an enquiry into morality, and why justice and goodness are fundamental. Harmonious human beings are as necessary as a harmonious society, and Plato has profound things to say about many aspects of life. The dialogue contains the famous myth of the cave, in which only knowledge and wisdom will liberate man from regarding shadows as reality.

Greek Lives by Plutarch

Plutarch wrote forty-six biographies of eminent Greeks and Romans in a series of paired, or parallel, Lives. This selection of nine Greek lives includes Alexander the Great, Pericles, and Lycurgus, and the Lives are notable for their insights into personalities, as well as for what they reveal about such things as the Spartan regime and social system.

Antigone, Oedipus the King, Electra by Sophocles

In these three masterpieces Sophocles established the foundation of Western drama. His three central characters are faced with tests of their will and character, and their refusal to compromise their principles has terrible results. Antigone and Electra are bywords for female resolve, while Oedipus’ discovery that he has committed both incest and patricide has inspired much psychological analysis, and given his name to Freud’s famous complex.

Heading image: Porch of Maidens by Thermos. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A reading list of Ancient Greek classics appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Mohamed Sesay,

on 10/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Philosophy,

Aristotle,

Hume,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

causation,

philosophy of science,

Arts & Humanities,

efficient causation,

Greek philosophy,

philosophical debt,

Add a tag

Causation is now commonly supposed to involve a succession that instantiates some lawlike regularity. This understanding of causality has a history that includes various interrelated conceptions of efficient causation that date from ancient Greek philosophy and that extend to discussions of causation in contemporary metaphysics and philosophy of science. Yet the fact that we now often speak only of causation, as opposed to efficient causation, serves to highlight the distance of our thought on this issue from its ancient origins. In particular, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) introduced four different kinds of “cause” (aitia): material, formal, efficient, and final. We can illustrate this distinction in terms of the generation of living organisms, which for Aristotle was a particularly important case of natural causation. In terms of Aristotle’s (outdated) account of the generation of higher animals, for instance, the matter of the menstrual flow of the mother serves as the material cause, the specially disposed matter from which the organism is formed, whereas the father (working through his semen) is the efficient cause that actually produces the effect. In contrast, the formal cause is the internal principle that drives the growth of the fetus, and the final cause is the healthy adult animal, the end point toward which the natural process of growth is directed.

From a contemporary perspective, it would seem that in this case only the contribution of the father (or perhaps his act of procreation) is a “true” cause. Somewhere along the road that leads from Aristotle to our own time, material, formal and final aitiai were lost, leaving behind only something like efficient aitiai to serve as the central element in our causal explanations. One reason for this transformation is that the historical journey from Aristotle to us passes by way of David Hume (1711-1776). For it is Hume who wrote: “[A]ll causes are of the same kind, and that in particular there is no foundation for that distinction, which we sometimes make betwixt efficient causes, and formal, and material … and final causes” (Treatise of Human Nature, I.iii.14). The one type of cause that remains in Hume serves to explain the producing of the effect, and thus is most similar to Aristotle’s efficient cause. And so, for the most part, it is today.

However, there is a further feature of Hume’s account of causation that has profoundly shaped our current conversation regarding causation. I have in mind his claim that the interrelated notions of cause, force and power are reducible to more basic non-causal notions. In Hume’s case, the causal notions (or our beliefs concerning such notions) are to be understood in terms of the constant conjunction of objects or events, on the one hand, and the mental expectation that an effect will follow from its cause, on the other. This specific account differs from more recent attempts to reduce causality to, for instance, regularity or counterfactual/probabilistic dependence. Hume himself arguably focused more on our beliefs concerning causation (thus the parenthetical above) than, as is more common today, directly on the metaphysical nature of causal relations. Nonetheless, these attempts remain “Humean” insofar as they are guided by the assumption that an analysis of causation must reduce it to non-causal terms. This is reflected, for instance, in the version of “Humean supervenience” in the work of the late David Lewis. According to Lewis’s own guarded statement of this view: “The world has its laws of nature, its chances and causal relationships; and yet — perhaps! — all there is to the world is its point-by-point distribution of local qualitative character” (On the Plurality of Worlds, 14).

Admittedly, Lewis’s particular version of Humean supervenience has some distinctively non-Humean elements. Specifically — and notoriously — Lewis has offered a counterfactural analysis of causation that invokes “modal realism,” that is, the thesis that the actual world is just one of a plurality of concrete possible worlds that are spatio-temporally discontinuous. One can imagine that Hume would have said of this thesis what he said of Malebranche’s occasionalist conclusion that God is the only true cause, namely: “We are got into fairy land, long ere we have reached the last steps of our theory; and there we have no reason to trust our common methods of argument, or to think that our usual analogies and probabilities have any authority” (Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, §VII.1). Yet the basic Humean thesis in Lewis remains, namely, that causal relations must be understood in terms of something more basic.

And it is at this point that Aristotle re-enters the contemporary conversation. For there has been a broadly Aristotelian move recently to re-introduce powers, along with capacities, dispositions, tendencies and propensities, at the ground level, as metaphysically basic features of the world. The new slogan is: “Out with Hume, in with Aristotle.” (I borrow the slogan from Troy Cross’s online review of Powers and Capacities in Philosophy: The New Aristotelianism.) Whereas for contemporary Humeans causal powers are to be understood in terms of regularities or non-causal dependencies, proponents of the new Aristotelian metaphysics of powers insist that regularities and dependencies must be understood rather in terms of causal powers.

Should we be Humean or Aristotelian with respect to the question of whether causal powers are basic or reducible features of the world? Obviously I cannot offer any decisive answer to this question here. But the very fact that the question remains relevant indicates the extent of our historical and philosophical debt to Aristotle and Hume.

Headline image: Face to face. Photo by Eugenio. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr

The post Efficient causation: Our debt to Aristotle and Hume appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Raquel Fernandes,

on 9/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Aristotle,

perception,

sensory perception,

*Featured,

Sense,

Arts & Leisure,

classic philosophical texts,

Anna Marmodoro,

Aristotle on perceiving objects,

classic philosophy,

Books,

coffee,

Philosophy,

Add a tag

Imagine a possible world where you are having coffee with … Aristotle! You begin exchanging views on how you like the coffee; you examine its qualities – it is bitter, hot, aromatic, etc. It tastes to you this way or this other way. But how do you make these perceptual judgments? It might seem obvious to say that it is via the senses we are endowed with. Which senses though? How many senses are involved in coffee tasting? And how many senses do we have in all?

The question of how many senses we have is far from being of interest to philosophers only; perhaps surprisingly, it appears to be at the forefront of our thinking – so much so that it was even made the topic of an episode of the BBC comedy program QI. Yet, it is a question that is very difficult to answer. Neurologists, computer scientists and philosophers alike are divided on what the right answer might be. 5? 7? 22? Uncertainty prevails.

Even if the number of the senses is a question for future research to settle, it is in fact as old as rational thought. Aristotle raised it, argued about it, and even illuminated the problem, setting the stage for future generations to investigate it. Aristotle’s views are almost invariably the point of departure of current discussions, and get mentioned in what one might think unlikely places, such as the Harvard Medical School blog, the John Hopkins University Press blog, and QI. “Why did they teach me they are five?” says Alan Davies on the QI panel. “Because Aristotle said it,” replies Stephen Fry in an eye blink. (Probably) the senses are in fact more than the five Aristotle identified, but his views remain very much a point of departure in our thinking about this topic.

Aristotle thought the senses are five because there are five types of perceptible properties in the world to be experienced. This criterion for individuating the senses has had a very longstanding influence, in many domains including for example the visual arts.

Yet, something as ‘mundane’ as coffee tasting generates one of the most challenging philosophical questions, and not only for Aristotle. As you are enjoying your cup of coffee, you appreciate its flavor with your senses of taste and smell: this is one experience and not two, even if two senses are involved. So how do senses do this? For Aristotle, no sense can by itself enable the perceiver to receive input of more than one modality, precisely because uni-modal sensitivity is what according to Aristotle identifies uniquely each sense. On the other hand, it would be of no use to the perceiving subject to have two different types of perceptual input delivered by two different senses simultaneously, but as two distinct perceptual contents. If this were the case, the difficulty would remain unsolved. In which way would the subject make a perceptual judgment (e.g. about the flavor of the coffee), given that not one of the senses could operate outside its own special perceptual domain, but perceptual judgment presupposes discriminating, comparing, binding, etc. different types of perceptual input? One might think that perceptual judgments are made at the conceptual rather than perceptual level. Aristotle (and Plato) however would reject this explanation because they seek an account of animal perception that generalizes to all species and is not only applicable to human beings. In sum, for Aristotle to deliver a unified multimodal perceptual content the senses need to somehow cooperate and gain access in some way to each other’s special domain. But how do they do this?

A sixth sense? Is that the solution? Is this what Aristotle means when talking about the ‘common’ sense? There cannot be room for a sixth sense in Aristotle’s theory of perception, for as we have seen each sense is individuated by the special type of perceptible quality it is sensitive to, and of these types there are only five in the world. There is no sixth type of perceptible quality that the common sense would be sensitive to. (And even if there were a sixth sense so individuated, this would not solve the problem of delivering multimodal content to the perceiver, because the sixth sense would be sensitive only to its own special type of perceptibles). The way forward is then to investigate how modally different perceptual contents, each delivered by one sense, can be somehow unified, in such a way that my perceptual experience of coffee may be bitter and hot at once. But how can bitter and hot be unified?

Modeling (metaphysically) of how the senses cooperate to deliver to the perceiving subject unified but complex perceptual content is another breakthrough Aristotle made in his theory of perception. But it is much less known than his criterion for the senses’ individuation. In fact, Aristotle is often thought to have given an ad hoc and unsatisfactory solution to the problem of multimodal binding (of which tasting the coffee’s flavor is an instance), by postulating that there is a ‘common’ sense that somehow enables the subject to perform all the perceptual functions that the five sense singly cannot do. It is timely to take a departure form this received view which does not pay justice to Aristotle’s insights. Investigating Aristotle’s thoughts on complex perceptual content (often scattered among his various works, which adds to the interpretative challenge) reveals a much richer theory of perception that it is by and large thought he has.

If the number of the senses is a difficult question to address, how the senses combine their contents is an even harder one. Aristotle’s answer to it deserves at least as much attention as his views on the number of the senses currently receive in scholarly as well as ‘popular’ culture.

Headline image credit: Coffee. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Coffee tasting with Aristotle appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 7/11/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Technology,

science,

Philosophy,

VSI,

climate change,

Very Short Introductions,

Aristotle,

engineering,

sophia,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

nicomachean ethics,

David Blockley,

episteme,

practical wisdom,

phronesis,

nous,

techne,

theoria,

Add a tag

By David Blockley

“Some people who do not possess theoretical knowledge are more effective in action (especially if they are experienced) than others who do possess it.”

Aristotle was referring, in his Nicomachean Ethics, to an attribute called practical wisdom – a quality that many modern engineers have – but our western intellectual tradition has completely lost sight of. I will describe briefly what Aristotle wrote about practical wisdom, argue for its recognition and celebration and state that we need consciously to utilise it as we face up to the uncertainties inherent in the engineering challenges of climate change.

Necessarily what follows is a simplified account of complex and profound ideas. Aristotle saw five ways of arriving at the truth – he called them art (ars, techne), science (episteme), intuition (nous), wisdom (sophia), and practical wisdom – sometimes translated as prudence (phronesis). Ars or techne (from which we get the words art and technical, technique and technology) was concerned with production but not action. Art had a productive state, truly reasoned, with an end (i.e. a product) other than itself (e.g. a building). It was not just a set of activities and skills of craftsman but included the arts of the mind and what we would now call the fine arts. The Greeks did not distinguish the fine arts as the work of an inspired individual – that came only after the Renaissance. So techne as the modern idea of mere technique or rule-following was only one part of what Aristotle was referring to.

Episteme (from which we get the word epistemology or knowledge) was of necessity and eternal; it is knowledge that cannot come into being or cease to be; it is demonstrable and teachable and depends on first principles. Later, when combined with Christianity, episteme as eternal, universal, context-free knowledge has profoundly influenced western thought and is at the heart of debates between science and religion. Intuition or nous was a state of mind that apprehends these first principles and we could think of it as our modern notion of intelligence or intellect. Wisdom or sophia was the most finished form of knowledge – a combination of nous and episteme.

Aristotle thought there were two kinds of virtues, the intellectual and the moral. Practical wisdom or phronesis was an intellectual virtue of perceiving and understanding in effective ways and acting benevolently and beneficently. It was not an art and necessarily involved ethics, not static but always changing, individual but also social and cultural. As an illustration of the quotation at the head of this article, Aristotle even referred to people who thought Anaxagoras and Thales were examples of men with exceptional, marvelous, profound but useless knowledge because their search was not for human goods.

Aristotle thought of human activity in three categories praxis, poeisis (from which we get the word poetry), and theoria (contemplation – from which we get the word theory). The intellectual faculties required were phronesis for praxis, techne for poiesis, and sophia and nous for theoria.

Sculpture of Aristotle at the Louvre Museum. Photo by Eric Gaba, CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

It is important to understand that theoria had total priority because sophia and nous were considered to be universal, necessary and eternal but the others are variable, finite, contingent and hence uncertain and thus inferior.

What did Aristotle actually mean when he referred to phronesis? As I see it phronesis is a means towards an end arrived at through moral virtue. It is concerned with “the capacity for determining what is good for both the individual and the community”. It is a virtue and a competence, an ability to deliberate rightly about what is good in general, about discerning and judging what is true and right but it excludes specific competences (like deliberating about how to build a bridge or how to make a person healthy). It is purposeful, contextual but not rule-following. It is not routine or even well-trained behaviour but rather intentional conduct based on tacit knowledge and experience, using longer time horizons than usual, and considering more aspects, more ways of knowing, more viewpoints, coupled with an ability to generalise beyond narrow subject areas. Phronesis was not considered a science by Aristotle because it is variable and context dependent. It was not an art because it is about action and generically different from production. Art is production that aims at an end other than itself. Action is a continuous process of doing well and an end in itself in so far as being well done it contributes to the good life.

Christopher Long argues that an ontology (the philosophy of being or nature of existence) directed by phronesis rather than sophia (as it currently is) would be ethical; would question normative values; would not seek refuge in the eternal but be embedded in the world and be capable of critically considering the historico-ethical-political conditions under which it is deployed. Its goal would not be eternal context-free truth but finite context-dependent truth. Phronesis is an excellence (arête) and capable of determining the ends. The difference between phronesis and techne echoes that between sophia and episteme. Just as sophia must not just understand things that follow from first principles but also things that must be true, so phronesis must not just determine itself towards the ends but as arête must determine the ends as good. Whereas sophia knows the truth through nous, phronesis must rely on moral virtues from lived experience.

In the 20th century quantum mechanics required sophia to change and to recognise that we cannot escape uncertainty. Derek Sellman writes that a phronimo will recognise not knowing our competencies, i.e. not knowing what we know, and not knowing our uncompetencies, i.e. not knowing what we do not know. He states that a longing for phronesis “is really a longing for a world in which people honestly and capably strive to act rightly and to avoid harm,” and he thinks it is a longing for praxis.

In summary I think that one way (and perhaps the only way) of dealing with the ‘wicked’ uncertainties we face in the future, such as the effects of climate change, is through collaborative ‘learning together’ informed by the recognition, appreciation, and exercise of practical wisdom.

Professor Blockley is an engineer and an academic scientist. He has been Head of the Department of Civil Engineering and Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Bristol. He is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Institution of Structural Engineers, and the Royal Society of Arts. He has written four books including Engineering: A Very Short Introduction and Bridges: The science and art of the world’s most inspiring structures.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS., and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Practical wisdom and why we need to value it appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 5/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

alexander,

ancient greece,

Aristotle,

greece,

worthington,

alexander the great,

macedonia,

Classical history,

*Featured,

macedonian,

Art & Architecture,

Classics & Archaeology,

By the Spear,

Ian Worthington,

Macedonian Empire,

Philip II of Macedon,

macedonian,

including demosthenes,

spear,

History,

Add a tag

By Ian Worthington

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), King of Macedonia, ruled an empire that stretched from Greece in the west to India in the east and as far south as Egypt. The Macedonian Empire he forged was the largest in antiquity until the Roman, but unlike the Romans, Alexander established his vast empire in a mere decade. As well as fighting epic battles against enemies that far outnumbered him in Persia and India, and unrelenting guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan, this charismatic king, who was worshiped as a god by some subjects and only 32 when he died, brought Greek civilization to the East, opening up East to West as never before and making the Greeks realize they belonged to a far larger world than just the Mediterranean.

Yet Alexander could not have succeeded if it hadn’t been for his often overlooked father, Philip II (r. 359-336), who transformed Macedonia from a disunited and backward kingdom on the periphery of the Greek world into a stable military and economic powerhouse and conquered Greece. Alexander was the master builder of the Macedonian empire, but Philip was certainly its architect. The reigns of these charismatic kings were remarkable ones, not only for their time but also for what — two millennia later — they can tell us today. For example, Alexander had to deal with a large, multi-cultural subject population, which sheds light on contemporary events in culturally similar regions of the world and can inform makers of modern strategy.

-

Battle of Granicus, 334 BCE

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/2.jpg

West met East violently when Alexander crossed from Europe to Asia in 334 BCE. In bitter fighting with massive casualties Alexander overcame enemy armies to establish the largest ancient empire before the Roman.

-

Alexander the Great

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Alexander-bust.jpg

Alexander III ('the Great') was born in 356, the son of Philip II and his 4th wife Olympias, and died in Babylon in June 323.

-

Map of Macedonia and Greece

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/1.jpg

In far northern Greece, Macedonia was a political, military and economic backwater before the reign of Philip II (359-336); when he was assassinated in 336 he had conquered Thrace and Greece and doubled Macedonia's population.

-

Phalanx formation with sarissas

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Phalanx.jpg

Philip's military reforms created the formidable professional Macedonian army with new shock and awe tactics, training, and weaponry, including the deadly sarissa, a 14-16' spear with a sharp pointed iron head that impaled enemy infantrymen.

-

Bust of Aristotle

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/5.jpg

When his son Alexander was 14, Philip hired Aristotle, foremost intellectual of the day, as his tutor. Aristotle taught Alexander for 3 years, turning him into an intellectual who spread Greek culture in the East.

-

Mosaic of Alexander the Great, Pompeii

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/6.jpg

Alexander the intellectual was nowhere near Alexander the warrior. In 333 BCE he battled Darius III, Great King of Persia, at Issus, forcing him to flee the battlefield. This was the beginning of the end for the ruling Achaemenid dynasty. This famous mosaic was discovered buried under Vesuvius' ash at Pompeii and is modelled on a contemporary painting showing Alexander bearing down on Darius, who is surrounded by the Macedonians' sarissas.

-

Death of Alexander the Great

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/8.jpg

Alexander died in Babylon in June 323 BCE. he had not left an undisputed heir, so his generals carved up his empire among themselves, bringing to an end what Philip and Alexander had fought so hard to achieve. Alexander's legacy and his failing as a king and a man question whether he deserves to be called great.

Ian Worthington is Curators’ Professor of History and Adjunct Professor of Classical Studies at the University of Missouri. He is the author of numerous books about ancient Greece, including Demosthenes of Athens and the Fall of Classical Greece and By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: 1. From By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Used with permission. 2. Bust of Alexander the Great at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek by Yair Haklai. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. 3. Map of Greece from By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Used with permission. 4. Macedonian phalanx by F. Mitchell, Department of History, United States Military Academy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 5. Aristotle Altemps Inv8575 by Jastrow. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. 6. Alexander Mosaic by Magrippa. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. 7. The Death of Alexander the Great after the painting by Karl von Piloty (1886). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in pictures appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Philosophy,

regress,

Plato,

chess,

Aristotle,

Wittgenstein,

thrashing,

Humanities,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Kant,

Gottlob Frege,

Graham Priest,

history of philosophy,

Nāgārjuna,

paraconsistent logic,

western philosophy,

pheidippides,

fruitfully,

Add a tag

By Graham Priest

If you go into a mathematics class of any university, it’s unlikely that you will find students reading Euclid. If you go into any physics class, it’s unlikely you’ll find students reading Newton. If you go into any economics class, you probably won’t find students reading Keynes. But if you go a philosophy class, it is not unusual to find students reading Plato, Kant, or Wittgenstein. Why? Cynics might say that all this shows is that there is no progress in philosophy. We are still thrashing around in the same morass that we have been thrashing around in for over 2,000 years. No one who understands the situation would be of this view, however.

So why are we still reading the great dead philosophers? Part of the answer is that the history of philosophy is interesting in its own right. It is fascinating, for example, to see how the early Christian philosophers molded the ideas of Plato and Aristotle to the service of their new religion. But that is equally true of the history of mathematics, physics, and economics. There has to be more to it than that—and of course there is.

Plato, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Great philosophical writings have such depth and profundity that each generation can go back and read them with new eyes, see new things in them, apply them in different ways. So we study the history of philosophy that we may do philosophy.

One of my friends said that he regards the history of philosophy as rather like a text book of chess openings. Just as it is part of being a good chess player to know the openings, it is part of being a good philosopher to know standard views and arguments, so that they can pick them up and run with them.

There is a lot of truth in this analogy, but it sells the history of philosophy short as well. Chess is pursued within a fixed and determinate set of rules. These cannot be changed. But part of good philosophy (like good art) involves breaking the rules. Past philosophers may have played by various sets of rule; but sometimes we can see their projects and ideas can fruitfully (perhaps more fruitfully) be articulated in different frameworks—perhaps frameworks of which they could have had no idea—and so which can plumb their ideas to depths of which they were not aware.

Such is my view anyway. It is certainly one that I try to put into practice in my own teaching and writing. I find that using the tools of modern formal logic is a particularly fruitful way of doing this. Let me give a couple of examples.

One debate in contemporary metaphysics concerns how the parts of an object cooperate to produce the unity which they constitute. The problem was put very much on the agenda by the great 19th century German philosopher and logician Gottlob Frege. Consider the thought that Pheidippides runs. This has two parts, Pheidippides and runs. But the thought is not simply a list, <Pheidippides, runs>. Somehow, the two parts join together. But how? Frege’s answer (we do not need to go in the details) ran into apparently insuperable problems.

Aristotle went part of the way to solving the problem over two millenia ago. He suggested that there must be something which joins the parts together, the form (morphe), F, of the proposition. But that can be only a start, as a number of the Medieval European philosophers noted. For <Pheidippides, F, runs> seems just as much a list as our original one, so there has to be something which joins all these things together—and we are off on a vicious infinite regress.

The regress is broken if F is actually identical with Pheidippides and runs. For then nothing is required to join F and Pheidippides: they are the same. Similarly for F and runs. But Pheidippides and runs are obviously not identical. So identity is not, as logicians say, transitive. You can have a=b and b=c without a=c. It is not clear that this is even a coherent possibility. Yet it is, as modern techniques in a branch of logic called paraconsistent logic can be used to show. I spare you the details.

A quite different problem concerns the topic in modern metaphysics called grounding. Some things depend for their existence on others. Thus, a chair depends for its existence on the molecules which are its parts; these, in turn, depend for their existence on the atoms which are their parts; and so on.

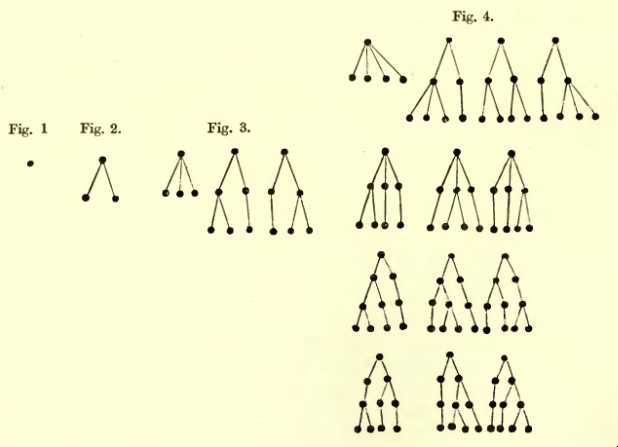

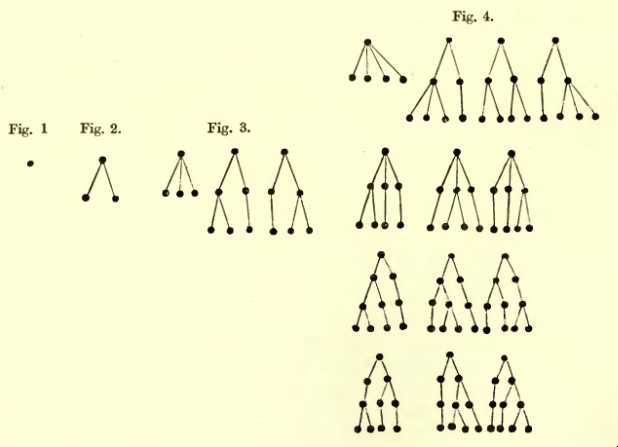

It contemporary debates, it is standardly assumed that this process must ground out in some fundamental bedrock of reality. That idea was attacked by the great Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna (c. 2c CE), with a swathe of arguments. Ontological dependence never terminates: everything depends on other things. Again, it is not clear, Nāgārjuna’s arguments notwithstanding, that the idea is coherent. If everything depends on other things, we have an obvious regress; and, it might well be thought, the regress is vicious. In fact, it is not. It can be shown to be coherent by a mathematical model employing mathematical structures called trees, all of whose branches may be infinitely long. Again, I spare you the details.

Of course, in explaining my two examples, I have slid over many important complexities and subtleties. However, they at least illustrate how the history of philosophy provides a mine of ideas. The ideas are by no means dead. They have potentials which only more recent developments—in the case of my examples, in contemporary logic and mathematics—can actualize. Those who know only the present of philosophy, and not the past, will never, of course, see this. That is why philosophers study the history of philosophy.

Graham Priest was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and the London School of Economics. He has held professorial positions at a number of universities in Australia, the UK, and the USA. He is well known for his work on non-classical logic, and its application to metaphysics and the history of philosophy. He is author of One: Being an Investigation into the Unity of Reality and of its Parts, including the Singular Object which is Nothingness.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: Bust of Plato, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Image of a graph as mathematical structure showing all trees with 1, 2, 3, or 4 leaves, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosophy and its history appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 2/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

classics,

Philosophy,

Oxford,

balloon,

Multimedia,

Wuthering Heights,

pride and prejudice,

austen,

OWC,

bookshop,

Aristotle,

Oxford World's Classics,

Humanities,

Jekyll and Hyde,

*Featured,

poetic edda,

cranford,

Images & Slideshows,

Classics & Archaeology,

a memoir of jane austen,

alexandra harris,

balloon debate,

blackwell's bookshop oxford,

nicomachean ethics,

oxford world's classics debate,

doole,

represented,

kirsty,

norrington,

Add a tag

By Kirsty Doole

Last week the Oxford World’s Classics team were at Blackwell’s Bookshop in Oxford to witness the first Oxford World’s Classics debate. Over three days we invited seven academics who had each edited and written introductions and notes for books in the series to give a short, free talk in the shop. This then culminated in an evening event in Blackwell’s famous Norrington Room where we held a balloon debated, chaired by writer and academic Alexandra Harris.

For those unfamiliar with balloon debates, this is the premise: the seven books, represented by their editors, are in a hot air balloon, and the balloon is going down fast. In a bid to climb back up, we’re going to have to throw some books out of the balloon… but which ones? Each editor spoke for five minutes in passionate defence of their titles before the audience voted. The bottom three books were then “thrown overboard”. The remaining four speakers had another three minutes each to further convince the audience, before the final vote was taken.

The seven books in our metaphorical balloon were:

Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell (represented by Dinah Birch)

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (represented by Helen Small)

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson (represented by Roger Luckhurst)

A Memoir of Jane Austen by James Edward Austen-Leigh (represented by Kathryn Sutherland)

The Poetic Edda (represented by Carolyne Larrington)

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (represented by Fiona Stafford)

The Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle (represented by Lesley Brown)

So who was saved? Find out in our slideshow of pictures from the event below:

-

The speakers

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Group-slide.jpg

All seven speakers plus chair, Alexandra Harris, prepare for the debate.

-

Alexandra Harris

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Harris-slide.jpg

Writer and academic Alexandra Harris chaired the event.

-

A selection of OWCs

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Table-slide.jpg

Just a few of the OWCs on sale during the event.

-

Dinah Birch on Cranford

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Birch-slide.jpg

Professor Dinah Birch defends Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell.

-

Helen Small on Wuthering Heights

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Small-slide.jpg

Professor Helen Small makes a plea to the audience to save Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

-

Roger Luckhurst on Jekyll and Hyde

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Luckhurst-slide.jpg

Professor Roger Luckhurst makes the case for saving the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

-

Kathryn Sutherland on A Memoir of Jane Austen

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Sutherland-slide.jpg

Professor Kathryn Sutherland argues in favour of saving A Memoir of Jane Austen by her nephew, J. E. Austen-Leigh.

-

Austen with meat cleaver

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Austen-slide.jpg

Kathryn Sutherland tries to boost her cause by bringing this mascot: Jane Austen holding a meat cleaver.

-

OWCs on the shelves

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Shelves-slide.jpg

Look at all our beautiful books!

-

Carolyne Larrington on The Poetic Edda

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Larrington-slide.jpg

Doing her bit for Old Norse, Dr Carolyne Larrington represents The Poetic Edda.

-

Fiona Stafford on Pride and Prejudice

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Stafford-slide.jpg

Would Professor Fiona Stafford succeed in saving Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice?

-

Lesley Brown on The Nicomachean Ethics

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Brown-slide.jpg

In the face of stiff literary competition, Lesley Brown strikes a blow for philosophy with a passionate defence of Aristotle's The Nicomachean Ethics.

-

Joint winner! The Poetic Edda

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Edda-slide.jpg

At the end of the debate we actually had a tie. Joint winners were The Poetic Edda and...

-

Joint winner! The Nicomachean Ethics

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Aristotle-slide.jpg

...The Nicomachean Ethics! Well done Carolyne and Lesley!

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All photos by Kirsty Doole

The post The great Oxford World’s Classics debate appeared first on OUPblog.

Be sure to read the first six parts of this essay:

Defining Plot Structure:

Defining Plot Structure:

If story structure is a form of organization for a story that may or may not have a plot, what is plot structure? It’s important to note that plot structure is a type of story structure, but the two terms are not interchangeable. The most common story shape for plot structure is the Fichtean Curve (see figure 4). Talked about at length in Gardner’s book The Art of Fiction, this plot structure reflects the goal-oriented plot. In essence, the character has a goal and follows a series of three or more obstacles of increasing intensity in order to achieve that goal. The protagonist reaches an ultimate conflict called the climax and then proceeds to a resolution. This common story shape is often called the Aristotelian Story Shape. However, this may be a falsehood. Aristotle only mentioned that stories should have beginnings, middles, and ends (hence the three act structure). Aristotle had very little to say about plot structure according to author M.T. Anderson:

Structurally in terms of abstract story shape, Aristotle doesn’t really give us much of a pointer. He says ‘for every tragedy there is a complication and a denouement. By complication I mean everything from the beginning, as far as the part that immediately precedes the transformation to prosperity or affliction. And by denouement, I mean the start of the transformation to the end.’ So, it is really more of a two part thing, and he gives you no real sense of the proportion those two things should be in. It’s not actually tremendously useful.

Thus the story shape (the Fichtean curve) came later as others developed new theories of plot structure.

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

Another common shape is Freytag’s Pyramid, (also called Freytag’s Triangle) which many illustrate with close similarity to the Fichtean curve (see figure 5A). However, this is a distortion, and Freytag’s pyramid is actually symmetrical in its triangular form (see figure 5B), and reflects a Germanic idea of story shape (Anderson). Despite the name, this common plot-structure includes the elements of: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and a Denouncement. It’s also very popular as Klien points out:

You can see this structure everywhere. It’s Aristotle’s Greek tragedies. It’s all six Jane Austen novels. It’s in all six Harry Potters. It’s mystery novels, romance novels, most every pop song ever written, U2, Stevie Wonder. And the reason for that is, again, catharsis: all the emotion building up through your interest in the characters and their actions, exploding at the climax, leaving you drained but renewed. (Klein, 10

By: Lauren,

on 5/27/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

a high price,

aipac,

daniel byman,

final solution,

jewish state,

machina,

peace in the middle east,

sisyphus,

mythology,

greek mythology,

Middle East,

Obama,

israel,

zion,

foreign policy,

Plato,

Aristotle,

Thought Leaders,

palestine,

jihad,

netanyahu,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

counterterrorism,

Add a tag

OPINION ·

Read part 1 of this article.

By Louis René Beres

Today, Israel’s leadership, continuing to more or less disregard the nation’s special history, still acts in ways that are neither tragic nor heroic. Unwilling to accept the almost certain future of protracted war and terror, one deluded prime minister after another has sought to deny Israel’s special situation in the world. Hence, he or she has always been ready to embrace, unwittingly, then-currently-fashionable codifications of collective suicide.

In Washington, President Barack Obama is consciously shaping these particular codifications, not with any ill will, we may hope, but rather with all of the usual diplomatic substitutions of rhetoric for an authentic intellectual understanding. For this president, still sustained by an utterly cliched “wisdom,” peace in the Middle East is just another routine challenge for an assumed universal reasonableness and clever presidential speechwriting.

Human freedom is an ongoing theme in Judaism, but this sacred freedom can never countenance a “right” of collective disintegration. Individually and nationally, there is always a binding Jewish obligation to choose life. Faced with the “blessing and the curse,” both the solitary Jew, and the ingathered Jewish state, must always come down in favor of the former.

Today, Israel, after Ariel Sharon’s “disengagement,” Ehud Olmert’s “realignment,” Benjamin Netanyahu’s hopes for “Palestinian demilitarization,” and U.S. President Barack Obama’s “New Middle East,” may await, at best, a tragic fate. At worst, resembling the stark and minimalist poetics of Samuel Beckett, Israel’s ultimate fate could be preposterous.

True tragedy contains calamity, but it must also reveal greatness in trying to overcome misfortune.

For the most part, Jews have always accepted the obligation to ward off disaster as best they can.

For the most part, Jews generally do understand that we humans have “free will.” Saadia Gaon included freedom of the will among the most central teachings of Judaism, and Maimonides affirmed that all human beings must stand alone in the world “to know what is good and what is evil, with none to prevent him from either doing good or evil.”

For Israel, free will must always be oriented toward life, to the blessing, not to the curse. Israel’s binding charge must always be to strive in the obligatory direction of individual and collective self-preservation, by using intelligence, and by exercising disciplined acts of national will. In those circumstances where such striving would still be consciously rejected, the outcome, however catastrophic, can never rise to the dignifying level of tragedy.

The ancient vision of authentically “High Tragedy” has its origins in Fifth Century BCE Athens. Here, there is always clarity on one overriding point: The victim is one whom “the gods kill for their sport, as wanton boys do flies.” This wantonness, this caprice, is precisely what makes tragedy unendurable.

With “disengagement,” with “realignment,” with “Palestinian demilitarization,” with both Oslo, and the Road Map, Israel’s corollary misfortunes remain largely self-inflicted. The continuing drama of a Middle East Peace Process is, at best, a surreal page torn from Ionesco, or even from Kafka. Here, there is nary a hint of tragedy; not even a satisfyingly cathartic element that might have been drawn from Aeschylus, Sophocles or Euripides. At worst, and this is the more plausible characterization, Israel’s unhappy fate has been ripped directly from the utterly demeaning pages of irony and farce.

Under former Prime

By: Lauren,

on 5/27/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

a high price,

aipac,

daniel byman,

jewish state,

peace in the middle east,

sisyphus,

Literature,

mythology,

greek mythology,

Middle East,

Obama,

israel,

zion,

foreign policy,

Aristotle,

Thought Leaders,

palestine,

jihad,

netanyahu,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

counterterrorism,

Add a tag

OPINION ·

By Louis René Beres

Israel after Obama: a subject of tragedy, or mere object of pathos?

Israel, after President Barack Obama’s May 2011 speech on “Palestinian self-determination” and regional “democracy,” awaits a potentially tragic fate. Nonetheless, to the extent that Prime Minister Netanyahu should become complicit in the expected territorial dismemberments, this already doleful fate could quickly turn from genuine tragedy to pathos and abject farce.

“The executioner’s face,” sang Bob Dylan, “is always well-hidden.” In the particular case of Israel, however, the actual sources of existential danger have always been perfectly obvious. From 1948 until the present, virtually all of Israel’s prime ministers, facing periodic wars for survival, have routinely preferred assorted forms of denial, and asymmetrical forms of compromise. Instead of accepting the plainly exterminatory intent of both enemy states and terrorist organizations, these leaders have opted for incremental territorial surrenders.

Of course, this is not the whole story. During its very short contemporary life, Israel has certainly accomplished extraordinary feats in science, medicine, agriculture, education and industry. It’s military institutions, far exceeding all reasonable expectations, have fought, endlessly and heroically, to avoid any new spasms of post-Holocaust genocide.

Still, almost from the beginning, the indispensable Israeli fight has not been premised on what should have remained as an unequivocal central truth of the now-reconstituted Jewish commonwealth. Although unrecognized by Barack Obama, all of the disputed lands controlled by Israel do have proper Israeli legal title. It follows that any diplomatic negotiations resting upon alternative philosophic or jurisprudential premises must necessarily be misconceived.

Had Israel, from the start, fixedly sustained its own birthright narrative of Jewish sovereignty, without submitting to periodic and enervating forfeitures of both land and dignity, its future, although problematic, would at least have been tragic. But by choosing instead to fight in ways that ultimately transformed its stunning victories on the battlefield to abject surrenders at the conference table, this future may ultimately be written as more demeaning genre.

In real life, as well as in literature and poetry, the tragic hero is always an object of veneration, not a pitiable creature of humiliation. From Aristotle to Shakespeare to Camus, tragedy always reveals the very best in human understanding and purposeful action. Aware that whole nations, like the individual human beings who comprise them, are never forever, the truly tragic hero nevertheless does everything possible to simply stay alive.

For Israel, and also for every other imperiled nation on earth, the only alternative to tragic heroism is humiliating pathos. By their incessant unwillingness to decline any semblance of a Palestinian state as intolerable (because acceptance of “Palestine” in any form would be ruthlessly carved out of the living body of Israel), Israel’s leaders have created a genuinely schizophrenic Jewish reality in the “new” Middle East. This is a Jewish state that is, simultaneously, unimaginably successful and incomparably vulnerable. Not surprisingly, over time, the result will be an increasingly palpable national sense of madness.

Perhaps, more than any other region on earth, the Jihadi Middle East and North Africa is “governed” by unreason. Oddly, this very reasonable observation is reinforced rather than contradicted by the prevailing patterns of “democratic re

By:

Joe Sottile,

on 3/15/2011

Blog:

Joe Silly Sottile's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

joy,

pain,

Dickinson,

emotion,

Plato,

Aristotle,

Gibran,

Eliot,

John F. Kennedy,

author talks,

best quotes,

writers. poets,

Ginsberg,

famous poets,

Joubert,

Add a tag

Poetryis finer and more philosophical than history; for poetry expresses theuniversal, and history only the particular.

Poetryis not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not theexpression of personality but an escape from personality. But, of course, onlythose we have personality and emotion know what it means to want to escape fromthese things.

T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) American-English poet andplaywright. IfI feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that ispoetry.

0 Comments on Poets Talking About Poetry as of 3/15/2011 9:39:00 PM

I probably achieve utter absurdity with my new Strange Horizons column, "A Story About Plot", wherein, like an awkward and amateur trapeze artist who has decided the key to success is to not believe in gravity, I try to link John Grisham, Nora Roberts, Aristotle, Shklovsky, and Peter Straub. The whole thing is, I expect, more a sign of my inevitable insanity than anything else.

By: Rebecca,

on 7/9/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

experimental,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

universe,

questions,

Aristotle,

experimental philosophy,

feel,

Hume,

Knobe,

Netzche,

Nichols,

think,

morally,

philosophers,

logical,

inevitable,

responsible,

Add a tag

Experimental philosophy is a new movement that seeks to return the discipline of philosophy to  a focus on questions about how people actually think and feel. In Experimental Philosophy we get a thorough introduction to the major themes of work in experimental philosophy and theoretical significance of this new research. Editors Joshua Knobe and Shaun Nichols have been kind enough to explain this all in simple terms below. Joshua Knobe is an assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Shaun Nichols is in the Philosophy Department and Cognitive Science Program at the University of Arizona. He also is the author of Sentimental Rules and co-author (with Stephen Stich) of Mindreading. Be sure to check out their Myspace page and their blog.

a focus on questions about how people actually think and feel. In Experimental Philosophy we get a thorough introduction to the major themes of work in experimental philosophy and theoretical significance of this new research. Editors Joshua Knobe and Shaun Nichols have been kind enough to explain this all in simple terms below. Joshua Knobe is an assistant professor in the philosophy department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Shaun Nichols is in the Philosophy Department and Cognitive Science Program at the University of Arizona. He also is the author of Sentimental Rules and co-author (with Stephen Stich) of Mindreading. Be sure to check out their Myspace page and their blog.

The reason the two of us first started doing philosophy is that we were interested in questions about the human condition. Back when we were undergraduates, we were captivated by the ideas we found in the work of philosophers like Nietzsche, Aristotle, and Hume. We wanted to follow in their tracks and think and write about human beings, their thoughts and feelings, the way they get along with each other, the nature of the mind.

Then we went to graduate school. What we found there was that the discipline of philosophy was no longer focused on questions about what human beings were really like. Instead, the focus was on a very technical, formal sort of philosophizing that was quite far removed from anything that got us interested in philosophy in the first place. This left us feeling disaffected, and a number of researchers at various other institutions felt the same way.

Together, several of these researchers developed the new field of experimental philosophy. The basic idea behind experimental philosophy is that we can make progress on the questions that interested us in the first place by looking closely at the way human beings actually understand their world. In pursuit of this objective, practitioners of this new approach go out and conduct systematic experimental studies of human cognition.

For example, in the traditional problem of free will, many philosophers have maintained that no one can be morally responsible if everything that happens is an inevitable consequence of what happened before. But the entire debate is conducted in a cold, logical manner. Experimental philosophers thought that maybe the way people actually think about these issues isn’t always so cold and logical. So first they tried posing the question of free will to ordinary people in a cold abstract manner. After describing a universe in which everything is inevitable, they asked participants, “In this Universe is it possible for a person to be fully morally responsible for their actions?” When the question was posed in this way, most people responded in line with those philosophers who claimed that no one can be responsible if everything is inevitable. But the experimentalists also wanted to see what would happen if people were given cases that got people more emotionally involved in the situation. So they once again described a universe in which everything that happens is inevitable, and then they asked a question that was sure to arouse strong emotions. It concerned a particular person in that Universe, Bill: “As he has done many times in the past, Bill stalks and rapes a stranger. Is it possible that Bill is fully morally responsible for raping the stranger?” Here the results were quite different. People tended to say that Bill was in fact morally responsible. So which reaction should we trust, the cold logical one or the emotionally involved one? This is the kind of question that experimental philosophy forces on us.

But that’s just one example. If you want to learn about more of the experimental studies that have been done, you can take a look at the recent articles on experimental philosophy in the New York Times and Slate.

ShareThis

Here's a lovely New York Times article waxing lyrical on the joys of the semi-colon and the elegance of correct punctuation. The piece is marred only by the correction that appears at the bottom:

An article in some editions on Monday about a New York City Transit employee’s deft use of the semicolon in a public service placard was less deft in its punctuation of the title of a book by Lynne Truss, who called the placard a “lovely example” of proper punctuation. The title of the book is “Eats, Shoots & Leaves” — not “Eats Shoots & Leaves.” (The subtitle of Ms. Truss’s book is “The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation.”)

How many characters are making the decisions at these decision points? Is the linearity of the story derived from the story following one character tracing one path through these nodes?