One day in 1668, the English diarist Samuel Pepys went shopping for a book to give his young French-speaking wife. He saw a book he thought she might enjoy, L’École des femmes or The School of Women, “but when I came to look into it, it is the most bawdy, lewd book that ever I saw,” he wrote, “so that I was ashamed of reading in it.” Not so ashamed, however, that he didn’t return to buy it for himself three weeks later — but “in plain binding…because I resolve, as soon as I have read it, to burn it, that it may not stand in the list of books, nor among them, to disgrace them if it should be found.” The next night he stole off to his room to read it, judging it to be “a lewd book, but what doth me no wrong to read for information sake (but it did hazer my prick para stand all the while, and una vez to decharger); and after I had done it, I burned it, that it might not be among my books to my shame.” Pepys’s coy detours into mock-Spanish or Franglais fail to conceal the orgasmic effect the lewd book had on him, and his is the earliest and most candid report we have of one reader’s bodily response to the reading of pornography. But what is “pornography”? What is its history? Was there even such a thing as “pornography” before the word was coined in the nineteenth century?

The announcement, in early 2013, of the establishment of a new academic journal to be called Porn Studies led to a minor flurry of media reports and set off, predictably, responses ranging from interest to outrage by way of derision. One group, self-titled Stop Porn Culture, circulated a petition denouncing the project, echoing the “porn wars” of the 1970s and 80s which pitted anti-censorship against anti-pornography activists. Those years saw an eruption of heated, if not always illuminating, debate over the meanings and effects of sexual representations; and if the anti-censorship side may seem to have “won” the war, in that sexual representations seem to be inescapable in the age of the internet and social media, the anti-pornography credo that such representations cause cultural, psychological, and physical harm is now so widespread as almost to be taken for granted in the mainstream press.

The brave new world of “sexting” and content-sharing apps may have fueled anxieties about the apparent sexualization of popular culture, and especially of young people, but these anxieties are anything but new; they may, in fact, be as old as culture itself. At the very least, they go back to a period when new print technologies and rising literacy rates first put sexual representations within reach of a wide popular audience in England and elsewhere in Western Europe: the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Most readers did not leave diaries, but Pepys was probably typical in the mixture of shame and excitement he felt when erotic works like L’École des filles began to appear in London bookshops from the 1680s on. Yet as long as such works could only be found in the original French or Italian, British censors took little interest in them, for their readership was limited to a linguistic elite. It was only when translation made such texts available to less privileged readers — women, tradesmen, apprentices, servants — that the agents of the law came to view them as a threat to what the Attorney General, Sir Philip Yorke, in an important 1728 obscenity trial, called the “public order which is morality.” The pornographic or obscene work is one whose sexual representations violate cultural taboos and norms of decency. In doing so it may lend itself to social and political critique, as happened in France in the 1780s and 90s, when obscene texts were used to critique the corruptions of the ancien régime; but the pornographic can also be used as a vehicle of debasement and violence, notably against women — which is one historical reality behind the US porn wars of the 1970s.

Pornography’s critics in the late twentieth or early twenty-first centuries have had less interest in the written word than in visual media; but recurrent campaigns to ban books by such authors as Judy Blume which aim to engage candidly with younger readers on sexual concerns suggest that literature can still be a battleground, as it was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Take, for example, the words of the British attorney general Dudley Ryder in the 1749 obscenity trial of Thomas Cannon’s Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d, a paean to male same-sex desire masquerading as an attack. Cannon, Ryder declared, aimed to “Debauch Poison and Infect the Minds of all the Youth of this Kingdom and to Raise Excite and Create in the Minds of all the said Youth most Shocking and Abominable Ideas and Sentiments”; and in so doing, Ryder contends, Cannon aimed to draw readers “into the Love and Practice of that unnatural detestable and odious crime of Sodomy.” Two and a half centuries ago, Ryder set the terms of our ongoing porn wars. Denouncing the recent profusion of sexual representations, he insists that such works create dangerous new desires and inspire their readers to commit sexual crimes of their own.

Then as now, attitudes towards sexuality and sexual representations were almost unbridgeably polarized. A surge in the popularity of pornographic texts was countered by increasingly severe campaigns to suppress them. Ironically, however, those very attempts to suppress could actually bring the offending work to a wider audience, by exciting their curiosity. No copies of Cannon’s “shocking and abominable” work survive in their original form; but the text has been preserved for us to read in the indictment that Ryder prepared for the trial against it. Eighty years earlier, after his encounter with L’École des femmes, Pepys guiltily burned the book, but at the same time immortalized the sensual, shameful experience of reading it. Of such contradictions is the long history of porn wars made.

The post Early Modern Porn Wars appeared first on OUPblog.

Recently, Locus published an online discussion of the work of Samuel R. Delany with a bunch of different writers and critics, primarily aimed at discussing Delany’s status as the newly-crowned Grand Master of the Science Fiction Writers of America. Plenty of interesting things are said there, and the participants include a number of people I’m very fond of (both as writers and people), but the particular focus ended up, I thought, creating a certain narrowness to the discussion, especially regarding the post-Dhalgren works, and I thought it might be nice to gather a different group of people together to discuss Delany … differently.So here we are. I put out the call to a wide variety of folks, and this is the group that responded. We used a Google Doc, and the discussion grew rhizomatically more than linearly, so you'll see that we sometimes refer to things said later in the roundtable. (This makes for a richer discussion, I think, but it may be a little jarring if you expect a linear conversation.)

I hope people who didn't have time or ability to join us in the "official" roundtable will feel free to offer their thoughts in the comments — as will, well, anybody else. Therefore, without further ado and all that jazz...

PARTICIPANTS

Matthew Cheney has published fiction and nonfiction in a wide variety of venues, including One Story, Locus, Weird Tales, Rain Taxi, and elsewhere. He wrote the introductions to Wesleyan University Press’s editions of Samuel R. Delany’s The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, Starboard Wine, and The American Shore (forthcoming). Currently, he is a student in the Ph.D. in Literature program at the University of New Hampshire. Craig Laurance Gidney is the author of Sea, Swallow Me & Other Stories and the YA novel Bereft. Geoffrey H. Goodwin is a journalist, author, and rogue academic with a Bachelor’s in Literary Theory (Syracuse University) and an MFA in Creative Writing (Naropa University). Geoffrey writes fiction; has taught composition and creative writing in a wide range of settings; has interviewed speculative writers and artists for Bookslut, Tor.com, Sirenia Digest, The Mumpsimus, and during Ann Vandermeer’s helming of Weird Tales; and has worked in seven different stores that have sold comic books. Keguro Macharia is a recovering academic, a lazy blogger, and an itinerant tweeter. Sometimes, he writes things on gukira.wordpress.com or tweets as @Keguro_Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Love is the Law and The Last Weekend. His short fiction has appeared everywhere from Asimov’s Science Fiction to The Mammoth Book of Threesomes and Moresomes.Njihia Mbitiru is a screenwriter. He lives in Nairobi.Lavelle Porter is an adjunct professor of English at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) and a Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. His dissertation The Over-Education of the Negro: Academic Novels, Higher Education and the Black Intellectual will be completed this spring. Finally. He’s on Twitter @alavelleporter.Ethan Robinson blogs, mostly about science fiction, at maroonedoffvesta.blogspot.com, a position he will no doubt shortly be parlaying into literary fame.Eric Schaller is a biologist, writer, and artist, living in New Hampshire and co-editor of The Revelator.THE ROUNDTABLEMatthew Cheney Locus is “The Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Field”, and so they’re primarily interested in science fiction. We don’t have to be that narrow here. But let’s start with one of the questions they start with, and see where we go: How has Delany influenced your own work or views on writing and literature? |

| detail of the cover of Dhalgren (Bantam, 1975) |

Geoffrey H. Goodwin: I got to spend a week with Chip, most minutes of every day, when he came and taught at my summer writing program when I was getting an MFA. A friend and I were the two second year science fiction devotees in the prose program (still not an easy spot in academe, though Chip has made that easier), so we knew that one of us could be his teaching assistant and decided to take it into our own hands. I remember the day Anne Waldman found out Chip was coming. I was in a poetry workship with her that day, so I raced to my friend and I swapped a fight over T.A.-ing for Chip to T.A. for Brian Evenson [who, by my reckoning, said some of the wisest comments in the other Delany roundtable] under the express agreement that my friend and I would both follow Chip around the whole time. So we did. Life-changing. Chip is still helping me learn and comprehend both literature and writing. His About Writing is one of my favorite books on the subject.

If one looks at his criticism, fiction, memoirs, and cultural relevance--not to mention everything else he’s accomplished--he’s incomparable. Sure, I remember how he offered the particle theory, where we read and read and then emit a particle on our own when we write, inspired by how we bombarded ourselves; or how he made sure to place the Marquis de Sade’s books within his young daughter’s reach because he wanted her to make her own choices about literature, and there were lessons and exercises in the workshop that were profound--but I also think of Chip as someone with whom I got to trade stories about Allen Ginsberg for stories about Philip K. Dick and Clive Barker. He’s a constellation in a tiny pantheon of living geniuses.

Nick Mamatas

I guess I appreciate Delany more as a reader than anything else. He doesn’t influence my writing, or my views. There are aspects of agreements, but I haven’t changed my mind about anything to coincide with Delany’s views. I always assign his book on writing—I’ve probably sold an extra fifty copies so far—not because I agree with everything in it, but because everything in it is worth tangling with.

Ethan Robinson

While discussions of Delany often focus on the beauty of his prose, his skillful "way with words" (usually with an example of some passage of heightened sensory description), for me this obscures one of the most remarkable aspects of his writing. It is true that he can indeed write quite beautifully when he needs to, but he is also willing to let himself write badly--that is, to take on modes of writing that are usually considered bad, clumsy, and really get to the heart of what it is that these modes are doing. I think in particular (but not exclusively) of his dialogue, which I find is very much of a piece with the generally derided style of the American science fiction magazines in its matter-of-factness, its often nakedly expository nature--even sometimes its flatness and lack of differentiation. For me it often calls to mind, say, the tendency of characters in Asimov and, later, McCaffrey (just two examples out of many possible) to talk to one another with bizarre thoroughness and "rational objectivity" about their own psychological makeups. In Delany the contrast between these passages of unattractive writing on the one hand and the heightened "poetic" passages on the other becomes a sort of structuring element, one that I think has been underappreciated and underexamined. And for myself, struggling in my own writing with the received notion that one must write "beautifully" (and/or inconspicuously; implied in both: homogeneously), seeing the value of occasional downright ugliness in Delany's writing has been very emboldening.Keguro Macharia I’ll lift Matt’s second prompt below--on beginnings--and track back to the Locus conversation, which started with “beginnings”: when did you first encounter Delany? Which is also a question about SF as a genre that (to my mind) obsesses about beginnings and endings (ecocides, genocides, monsters, hybrids, extinguishment, survival). Which is also to borrow from Lavelle about AIDS and Delany and, more broadly, the forms of extinguishment and disposability his work speaks to and, in doing so, enables us to speak about--this is the importance of Hogg as an early work. I first encountered Delany in the Patrick Merla anthology (Boys Like Us) that Lavelle mentions below. I don’t remember reading him then and, in fact, I suspect that I did not know how to read him at the time--I wanted a simple(r) narrative than he was willing to offer, a cleaner story that stayed “inside the lines,” affirmed identity, made the pleasures of identification simple, the practices of belonging uncomplicated. (Although Matt wants us to be polite, I’ll add that I read much of this impulse in the Locus discussion.)I re-encountered Delany through Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, just before I joined grad school. At the time, I was interested in formal innovation, and Times Square modeled the kind of writing and thinking I found necessary as a form of world building. I came to the novels later--Stars in My Pocket, Hogg, Mad Man, the Nevèrÿon series, at much the same time as I was reading Delany’s many essay collections. Delany helped me see form--why form matters, how form matters, to whom form matters, why formalism matters--as a project of world-building, world-remaking, inextricable from embodiment, desire, fantasy, and speculation.Njihia Mbitiru I have absolutely no idea, yet, about his influence on me. Others have spoken with great perspicacity--as well as humor (Brett Cox in the Locus roundtable being one)--about Delany’s influence. I suspect I’m still working through mine and therefore limited in what I can say about it. The first bit of Delany’s writing I encountered was The Towers of Toron, the first in the Fall of the Towers Trilogy. I was twenty-one, if I recall correctly. That was twelve years ago now. I’ve become an avid re-reader of his work, which has made me a re-reader of many other writers I onced-over. And because of this I would very much like to hazard that I am now a better reader, but this also remains to be seen: the simple fact is that proof of such is in writing, whose excellence, much as we strive toward our own finally idiosyncratic sense of it, is also a public affair.Matt: just to touch on what you’ve said about the narrative of certain of his writings--the later ones, beginning with Dhalgren (written in his late 20s and early 30s, you’ll recall! so that it’s hard to think of this as ‘late Delany’): I also resist and reject this narrative ( I’m not quite at resentment, but give me time). I find it completely non-sensical. Better and more honest to say, as a reader, that the game he’s hunting as a novelist in Dhalgren, Triton, the Neveryon series up into his present work doesn’t hold your interest. It’s a long way away from that to ‘difficult’. Only a very narrow reading of SF writing would support an assessment of Delany as ‘difficult’, if we’re talking about prose style (though I suspect that’s not what is meant, which begs the question: what do people mean exactly when they use the term ‘difficult’?). There’s so much at a SF readers’ disposal in terms of range and sophistication, or if you like, the absence of it, as there is in any other genre. I enjoy and appreciate Delany’s writing in no small part because it calls attention to precisely this.Eric Schaller Delany’s writings have influenced me more in my approach to life and thought than in writing itself. Some may dislike John Gardner’s concept and application of ‘moral fiction’ to literature, but I have always found Delany’s work moral in its suggestion of how to live a good life. In this respect, as a philosophy, I could abbreviate it as ‘compassionate individualism’: the importance of discovering and following your own path, the diversity of such paths within a population, and how to maintain your personal dignity without selfishly depriving others of theirs. The dedication in Heavenly Breakfast ("This book is dedicated to everyone who ever did anything no matter how sane or crazy whether it worked or not to give themselves a better life"), when I read it in college brought tears to my eyes, and still does.Through Delany’s writings, I like to think that I became more intentionally aware. My discovery that Delany was gay—not necessarily obvious from his earlier novels, which featured plenty of male-female couples, or from his earlier biographical information which sometimes mentioned a marriage—more specifically the worlds revealed in his non-fictional/autobiographical works such as The Motion of Light in Water, the contemporary sections from “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” and, more recently, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue personified concerns that I would never experience directly. I donate to GMHC because of these works.

Matthew CheneyThere seems to be a narrative among science fiction fans, and particularly SF fans of a certain age, that there is The Good Delany of the pre-Dhalgren books, Hugo and Nebula Awards, etc. ... and then there is The Problematic Delany of Dhalgren and later. It’s a narrative of loss and disappointment, frequently accompanied by the question, “What happened?!” Because I was born in the year Dhalgren was, at least officially, published (it bears a January 1975 publication date, though it actually hit shelves a little earlier), and didn’t start reading Delany until either late 1987 or sometime in 1988, when the last Nevèrÿon book, The Bridge of Lost Desire (Return to Nevèrÿon) was published, my awareness of his career has always included what older, more traditional SF readers considered the “difficult” writings. It’s probably not surprising that I resist, reject, and resent this narrative.The book I’ve spent the most time with recently, because I’m working on a conference paper about it, is Dark Reflections, which is really beautiful and much more complexly structured than it seems at first, and which should be accessible to just about any audience, since it’s not at all pornographic and the complexity of the structure is subtle, making a basic reading relatively easy. Also, the book’s a great companion to About Writing, which it echoes often. (There’s some good discussion of the “accessibility” of Dark Reflections, particularly for heterosexual men, in Delany’s 2007 interview with Carl Freedman in Conversations with Samuel R. Delany.) But for various reasons, some having to do with events in the publishing industry, Dark Reflections does not seem to have been widely read, and is currently only in print as an e-book. It deserves a wide audience, though.So my questions for the roundtable are: What other, more useful, stories of Delany’s career could we tell? Is the Good Delany/Problematic Delany narrative useful in some way that I’m missing, some way that I can’t see because it just makes me so angry?Ethan Robinson I’ve not yet read any of his fiction after Trouble on Triton (at a certain point I decided to approach him chronologically and have been stalled at The Einstein Intersection, which my library doesn't have; I should just go ahead and buy it, probably), and haven't in fact read Dhalgren, so I can't say too much about this. But I will say that the way I see people talk about this is always very distressing to me as many of the points singled out as "problems" (too many "ideas," not enough action, unconventional storytelling, etc.) are precisely what draws me not only to Delany but to science fiction in the first place! I know the bulk of sf has always been written on a pretty, shall we say, basic level, but I confess I simply have no idea why people who want nothing but simplicity and action and conventional narrative would be attracted to this field, which seems to long for much more.

Craig Laurance Gidney

My first introduction to Delany was, interestingly enough, Dhalgren. My older brother had a copy of the book when it first came out in the ‘70s and I appropriated it. I read the book in bits and pieces during my teenaged years, and it formed my taste for esoteric and trippy SF. When people spoke about how difficult the book was, I had a hard time understanding them, maybe because I absorbed the idea of the non-linear and counter-factual texts so young. Everything of his I read is through the locus of Dhalgren. The earlier stuff is great to me because I can see the progression of themes that were refined in his later work.

Eric Schaller

I think some of the variable responses to Delany’s work may arise in part from what piece(s) were initially encountered, and how such initial experiences play into future expectations. I first encountered Delany’s work through several short stories read in high school. I remember how strongly “Time Considered as a Helix of Precious Stones” affected me, and took a perverse pleasure in the fact that my Dad didn’t follow the main character’s morphing names in the initial section. I also remember reading “Aye, and Gomorrah,” in Dangerous Visions, a story that I knew had to be important because Harlan Ellison said so. At first the story seemed slight, but it lingered and poked at my consciousness.

I don’t think I read a novel of Delany’s until the summer after graduating high school. I was working in New York City at Sloan Kettering and the novel was Dhalgren. There had been the joke published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction about the three things that mankind would never reach (“The core of the sun, the speed of light, and page 30 of Dhalgren”), but this if anything incited my interest in the novel. I was of the right age and in the right place to have the novel assume a central station in my life. But it is also one of those novels that I have returned to and re-read over the years, each time taking something new away from it. For instance, Delany having written that The Fall of the Towers was inspired by a painting of that title which did not show towers but rather reactions to their fall, I noticed a similar approach was often used in Dhalgren: the reactions of characters described before you understood to what they were reacting.

As an undergraduate at Michigan State, I sought out every Delany book I could find. And to my mind then, and still, there were differences in the approach to writing found in his early works to what I found in Dhalgren and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. The closest I can come to that difference is to say that in the earlier work Delany seemed to be thinking at a sentence to sentence level. With the later work, it seemed that he inhabited whole paragraphs at once; an individual sentence might not seem that powerful or poetic alone, but within the context of the paragraph it sang.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin

Re-reading the original Locus Roundtable, I can see how some of the context shifted based on the idea of “Samuel R. Delany, Grandmaster.” I know I think differently when “Grandmaster” gets added after anything and then we get the added aspect of, “Welcome to the Science Fiction canon,” by writers who, for no fault of their own, are far less accomplished than Chip. So we have a gay black beatnik who writes science fiction, essays, porn, comics, criticism, and just about everything else—and Chip is the kind of writer who can mean many different things to many different people. Paul Witcover’s review comparing Delany to Hendrix and Bowie really resonates with how I see Chip’s work—but Chip has kept at the work, continuing to evolve. F. Brett Cox nails it when he says Chip was producing books at different points in his life and Chip has always put himself into his books whether they were early SF, criticism, or memoir. And I’d agree that Chip isn’t cranking out spaceships or nuclear-ravaged earths the way the early works could seem—but I also swear that the ideas have been evolving since the beginning. I remember one of the earlier ones, Einstein maybe, where the chapter started with Chip quoting someone he’d talked to that week, citing it as a comment to the author. That level of intertextuality or interstitiality speaks to so much of what Chip has accomplished since then.

Nick Mamatas

As it turns out, people don’t like porn that isn’t for them. Further, most SF readers are pretty much at sea if they don’t have any tropes to think about. A straightforward and beautiful realist novel like Dark Reflections is just perplexing because it’s just about some guy living his life. No way!

I actually prefer his porn to his SF for the most part. It’s difficult to write transgressive, dirty, occasionally simply wrong stuff with such sympathy and warmth, but Delany manages it. He is an utterly unique writer in th

Ed Champion interviews Samuel Delany for his Bat Segundo Show. An informed, wide-ranging conversation that's very much worth the time to listen to:

Delany: And I think pornotopia is the place, as I’ve written about, where the major qualities — the major aspect of pornotopia, it’s a place where any relation, if you put enough pressure on it, can suddenly become sexual. You walk into the reception area of the office and you look at the secretary and the secretary looks at you and the next minute you’re screwing on the desk. That’s pornotopia. Which, every once in a while, actually happens. But it doesn’t happen at the density.

Correspondent: Frequency.

Delany: At the frequency that it happens in pornotopia. In pornotopia, it happens nonstop. And yet some people are able to write about that sort of thing relatively realistically. And some people aren’t. Something like Fifty Shades of Grey is not a very realistic account.

Correspondent: I’m sure you’ve read that by now.

Delany: I’ve read about five pages.

Correspondent: And it was enough for you to throw against the wall?

Delany: No. I didn’t throw it. I just thought it was hysterically funny. But because the writer doesn’t use it to make any real observations on the world that is the case, you know, it’s ho-hum.

Correspondent: How do we hook those moms who were so driven to Fifty Shades of Grey on, say, something like this?

Delany: I don’t think you’re going to.

From a rich, insightful, and fascinating review by Roger Bellin of Samuel Delany's Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders:It is certainly possible to find worthwhile the effort it takes to attempt the broadening of one's libidinal sympathies — the way a psychologically realistic novel can demand our sympathy with someone else's life and thoughts, this one demands our sympathy with his sexual desires. If science fiction, in Darko Suvin's definition, is the genre of "cognitive estrangement," then the pornographic first half of TVNS is a work of libidinal estrangement: the novel's alienating effect bears on its reader's desires, not his rational mind.

[...]

Rather than just cataloguing its protagonists' sex acts, TVNS gradually becomes a psychologically complicated novel about what they've learned from them — a reflection, through a host of little narrated daily incidents, on the ethical lessons that a life of joyous perversion has taught Eric and Shit. Sometimes it almost, implicitly, seems like a manifesto for a broad and catholic vision of queer politics; and the novel's real utopia might, finally, have less to do with the imagined community of the Dump than it does with the people themselves, and the practice of loving each other that they've discovered and worked out.

I'm still reading the book, slowly and with, frankly, awe, but everything Bellin says fits well with my reading so far.

More later, once I've reached the last page of the book...

By: Michelle,

on 3/29/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

emerging adult,

Jeremy Uecker,

Mark Regnerus,

premarital sex,

Premarital Sex in America,

sex before marriage,

sexual economics,

premarital,

marrying,

market,

wins,

Economics,

young adults,

Sociology,

winning,

Psychology,

sex,

marriage,

pornography,

porn,

sexual,

chart,

emerging,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Michelle Rafferty

As most of you probably know by now, there’s a new stage in life – emerging adulthood, or for the purposes of this post, the unmarried young adult. Marriage is getting pushed off (26 is now the average age for women, 28 for men) which means…more premarital sex than ever!

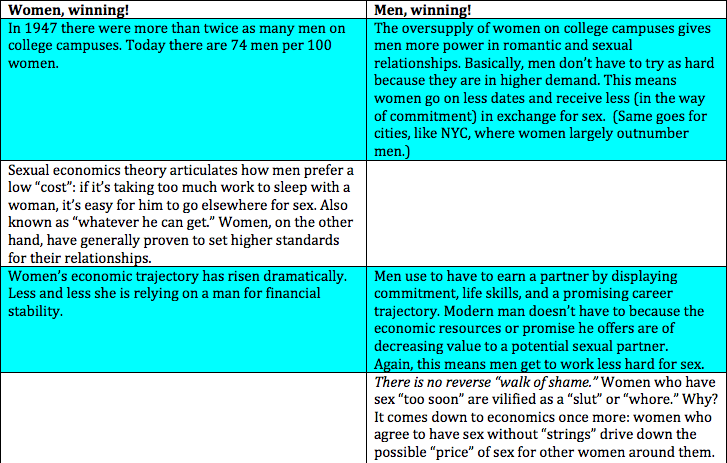

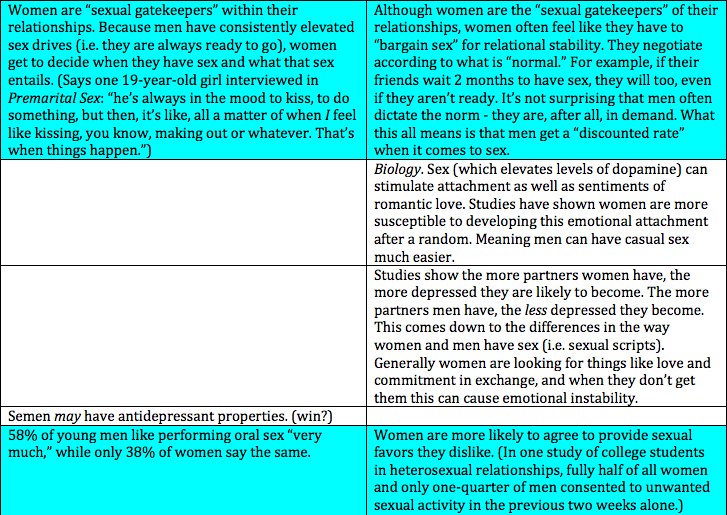

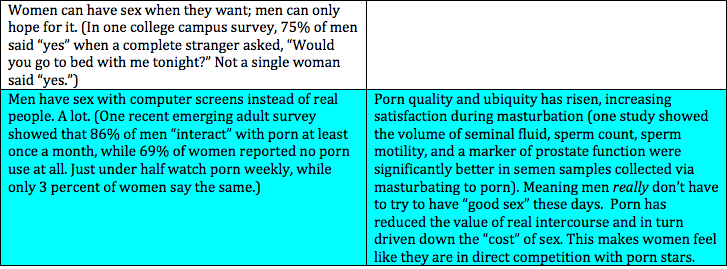

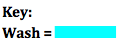

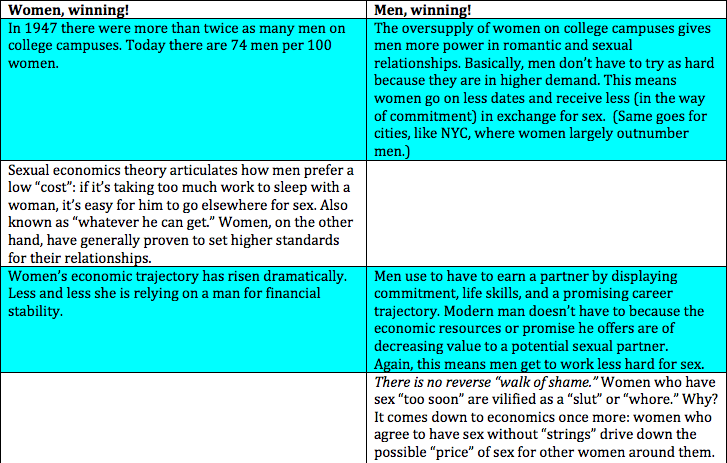

According to sociologists, emerging adults are all part of a sexual market in which the “cost” of sex for men and women in heterosexual relationships is pretty different. Out of this disparity has risen the theory of “sexual economics,” which I recently read up on in Premarital Sex in America: How Young Americans Meet, Mate, and Think about Marrying. At first glance women appeared to be the clear losers in this market. See this passage:

Sexual economics theory would argue that sex is about acquiring valued “resources” at least as much as it is about seeking pleasure. When most people think of women trading sex for resources, they think of prostitution and money as the terms of exchange. But this theory encourages us to think far more broadly about the resources that the average woman values and attempts to acquire in return for sex – things like love, attention, status, self-esteem, affection, commitment, and feelings of emotional union. Within many emerging adults’ relationships, orgasms are not often traded equally.

Basically, the sexual economics theory says that while women and men are doing the same thing during sex, socially they are doing two different things. Women can and do enjoy sex, but they also have an agenda, while men…just want to have sex. Which to me just seemed, well, sad. Hadn’t women all finally agreed that a man can’t ever make you happy, only you can? But the more I read up on the theory of sexual economics, the less cut-and-dry it became. Women might use sex to get commitment, but they’re also getting things like advanced degrees and independent financial stability - which also play a role in this new sexual economy. This led me to ask: are men really the clear winners in this game? I scoured the countless studies and interviews in Premartial Sex in America and came up with the following chart to sort all the data out.

Wins in the Emerging Adult Sexual Market by Gender

Tally:

Women &

By:

Elaine Anderson,

on 3/22/2009

Blog:

Fahrenheit 451: Banned Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

pornography,

Cambridge,

filtering software,

Bill 128,

children,

school,

sexual content,

Internet,

computer,

Add a tag

The Corporation of the City of Cambridge wants to force the Cambridge Public Library to install and use Internet Filtering Software on their computers. Councillor Tucci put forward the following Internet Filtering Proposal found in the City of Cambridge's Council agenda of February 9, 2009.

Councillor Tucci - Internet Filtering Software On Computers

Recommendation

WHEREAS there is no law in Ontario prohibiting pornography and other sexually explicit material from being viewed on computers in public schools and libraries;

AND WHEREAS there are public schools and public libraries that do not use

internet filtering software on computers that blocks such inappropriate material;

AND WHEREAS significant changes have occurred with respect computer technologies, software and programs that could filter access to inappropriate, explicit sexual content;

AND WHEREAS parents in the province of Ontario have the right to ensure

their children are protected from pornography and other inappropriate material available on the internet in their public schools and libraries;

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT the Council of The Corporation of the City of Cambridge petitions the Honorable M. Aileen Carrol, Minister of Culture, the Honorable Dalton McGuinty, Premier of Ontario and, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario to require all public schools and libraries in Ontario to be required to install internet filtering software on computers to avoid viewing of sites with inappropriate, explicit sexual content;

AND FURTHER THAT the motion once approved be forwarded to all MPPs representing Waterloo Region, to the Leader of the Official Opposition, to the Leader of the 3rd party and, through AMO, to all other municipalities for their consideration.

In 2004, a Cambridge man was arrested for using a city library computer to download child pornography, according to a story in The Record. In the fall of 2008, the Cambridge Public Library Board twice rejected the call for the use of filtering but promised to review the situation as technology advances. The City of Cambridge refused to force the library to purchase filtering software in January 2009. Cambridge Public Library is the only library system in Waterloo Region that doesn't use filters. The issue has been raised once again. Cambridge Council voted 4-3 to support Tucci's recommendation, calling on the Province of Ontario to force libraries to use Internet blocking software.

Cambridge MPP Gerry Martiniuk is pushing a private members' bill (Bill 128) that would put internet filtering rules in place. Private members bills are rarely passed into law. Councilor Gary Price, who sits on the Cambridge library board, pointed out that libraries have a mandate to provide free access to legal information and that filtering software can block legal sites as well as questionable ones.

Below is the text from Bill 128 which is relevant to schools and public libraries:

Education Act

Every school board is required to ensure that every school of the board has in place technology measures on all of the school’s computers to which a person under the age of 18 years has access. The technology measures must do the following:

1. They must block access on the Internet to any material,including written material, pictures and recordings, that is obscene or sexually explicit or that constitutes child pornography.

2. They must block access to any form of electronic communication, including electronic mail and chat rooms, if the communication could reasonably be expected to expose a person under the age of 18 years to any material,including written material, pictures and recordings, that is obscene or sexually explicit or that constitutes child pornography.

3. They must block access to any site on the Internet or to any form of electronic communication, including electronic mail and chat rooms, if the school has not authorized users of the computers to access the site or the communication or if the site or the communication could reasonably be expected to contain material that includes personal information about a person under the age of 18 years.

A school is required to have a policy on who are authorized to use its computers to which a person under the age of 18 years has access and to monitor the use that persons under the age of 18 years make of those computers.

Public Libraries Act

The Bill amends the Public Libraries Act to make amendments that are similar to those that the Bill makes to the Education Act, except that the duties of a school board are those a board with respect to every library under its jurisdiction and the duties of a school are those of a public library.

Read an article which gives alternatives to internet filtering.

The Pelham Public Library challenges you to take the Banned Book Challenge. This challenge will run until June 30, 2009.

Professor M. Gigi Durham, author of The Lolita Effect, contributes a provocative essay on sex and pornography on college campuses in the current issue of The Chronicle Review.

Professor M. Gigi Durham, author of The Lolita Effect, contributes a provocative essay on sex and pornography on college campuses in the current issue of The Chronicle Review.

"Last year," writes Durham, "the American Psychological Association convened a task force on the sexualization of young girls; the ensuing report documented the lasting harm done to girls by a culture in which they are constantly positioned as sexual objects. Worldwide, child pornography and child sex trafficking are burgeoning industries. Real-world sexual violence against women is almost epidemic."