Julie Danielson has done a lovely roundup of art and early sketches from DARWIN and a few other cool picture books over at her blog, Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast. Check it out! ♡

From the publication of the Origin, Darwin enthusiasts have been building a kind of secular religion based on its ideas, particularly on the dark world without ultimate meaning implied by the central mechanism of natural selection.

The post Darwinism as religion: what literature tells us about evolution appeared first on OUPblog.

How did it come to this? How was evolution transformed from a scientific principle of human-as-animal to a contentious policy battle concerning children’s education? From the mid-19th century to today, evolution has been in a huge tug-of-war as to what it meant and who, politically speaking, got to claim it.

The post The evolution of evolution appeared first on OUPblog.

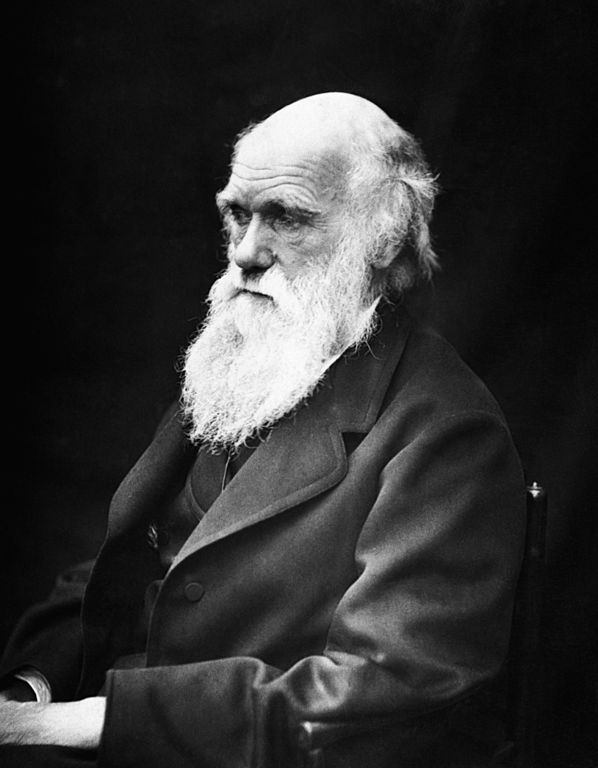

Charles Darwin was widely known as a travel writer and natural historian in the twenty years before On the Origin of Species appeared in 1859. The Voyage of the Beagle was a great popular success in the 1830s. But the radical theories developed in the Origin had been developed more or less in secret during those intervening twenty years.

The post The impact of On the Origin of Species appeared first on OUPblog.

Two other major and largely unsolved problems in evolution, at the opposite extremes of the history of life, are the origin of the basic features of living cells and the origin of human consciousness. In contrast to the questions we have just been discussing, these are unique events in the history of life.

The post Evolution: Some difficult problems appeared first on OUPblog.

The agents of natural selection cause evolutionary changes in population gene pools. They include a plethora of familiar abiotic and biotic factors that affect growth, development, and reproduction in all living things.

The post The hidden side of natural selection appeared first on OUPblog.

As the 2016 presidential election season begins (US politics, unlike nature, has seasons that are two years long), we will once again see Republican politicians ducking questions about the validity of evolution. Scott Walker did that recently in response to a London interviewer. During the previous campaign, Rick Perry answered the question by observing that there are “some gaps” in the theory of evolution and that creationism is taught in the Texas public schools (it isn’t, of course).

The post The dangers of evolution denial appeared first on OUPblog.

When Charles Darwin died at age 73 on this day 133 years ago, his physicians decided that he had succumbed to “degeneration of the heart and greater vessels,” a disorder we now call “generalized arteriosclerosis.” Few would argue with this diagnosis, given Darwin’s failing memory, and his recurrent episodes of “swimming of the head,” “pain in the heart”, and “irregular pulse” during the decade or so before he died.

The post Darwin’s “gastric flatus” appeared first on OUPblog.

I haven't forgotten about you, little blog. I've just been knee-deep in revisions, and now final art (yay!) for Charles Around The World.

I'm posting a lot more frequently over on Instagram, if you'd like to follow along...

Imagine a plant that grew into a plum pudding, a cricket bat, or even a pair of trousers. Rather than being a magical transformation straight out of Cinderella, these ‘wonderful plants’ were instead to be found in Victorian Britain. Just one of the Fairy-Tales of Science introduced by chemist and journalist John Cargill Brough in his ‘book for youth’ of 1859, these real-world connections and metamorphoses that traced the origins of everyday objects were arguably even more impressive than the fabled conversion of pumpkin to carriage (and back again).

The post Cinderella science appeared first on OUPblog.

Charles Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection changed the way scientists understood our evolutionary past, and is a concept with which most people are quite familiar. One often overlooked element of Natural Selection, however, is the role that chance plays in guiding this process. In Darwin’s Dice: The Idea of Chance in the Thought of Charles Darwin, Curtis Johnson examines many of Darwin’s most significant writings through this lens. Celebrate Darwin Day by discovering the important role chance plays in Darwinian Theory.

Image Credit: “Evolution Schmevolution.” Photo by Brent Danley. CC by NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Darwin’s dice [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

I recall a dinner conversation at a symposium in Paris that I organized in 2010, where a number of eminent evolutionary biologists, economists and philosophers were present. One of the economists asked the biologists why it was that whenever the topic of “group selection” was brought up, a ferocious argument always seemed to ensue. The biologists pondered the question. Three hours later the conversation was still stuck on group selection, and a ferocious argument was underway.

Group selection refers to the idea that natural selection sometimes acts on whole groups of organisms, favoring some groups over others, leading to the evolution of traits that are group-advantageous. This contrasts with the traditional ‘individualist’ view which holds that Darwinian selection usually occurs at the individual level, favoring some individual organisms over others, and leading to the evolution of traits that benefit individuals themselves. Thus, for example, the polar bear’s white coat is an adaptation that evolved to benefit individual polar bears, not the groups to which they belong.

The debate over group selection has raged for a long time in biology. Darwin himself primarily invoked selection at the individual level, for he was convinced that most features of the plants and animals he studied had evolved to benefit the individual plant or animal. But he did briefly toy with group selection in his discussion of social insect colonies, which often function as highly cohesive units, and also in his discussion of how self-sacrificial (‘altruistic’) behaviours might have evolved in early hominids.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the group selection hypothesis was heavily critiqued by authors such as G.C. Williams, John Maynard Smith, and Richard Dawkins. They argued that group selection was an inherently weak evolutionary mechanism, and not needed to explain the data anyway. Examples of altruism, in which an individual performs an action that is costly to itself but benefits others (e.g. fighting an intruder), are better explained by kin selection, they argued. Kin selection arises because relatives share genes. A gene which causes an individual to behave altruistically towards its relatives will often be favoured by natural selection—since these relatives have a better than random chance of also carrying the gene. This simple piece of logic tallies with the fact that empirically, altruistic behaviours in nature tend to be kin-directed.

Strangely, the group selection controversy seems to re-emerge anew every generation. Most recently, Harvard’s E.O. Wilson, the “father of sociobiology” and a world-expert on ant colonies, has argued that “multi-level selection”—essentially a modern version of group selection—is the best way to understand social evolution. In his earlier work, Wilson was a staunch defender of kin selection, but no longer; he has recently penned sharp critiques of the reigning kin selection orthodoxy, both alone and in a 2010 Nature article co-authored with Martin Nowak and Corina Tarnita. Wilson’s volte-face has led him to clash swords with Richard Dawkins, who says that Wilson is “just wrong” about kin selection and that his most recent book contains “pervasive theoretical errors.” Both parties point to eminent scientists who support their view.

What explains the persistence of the controversy over group and kin selection? Usually in science, one expects to see controversies resolved by the accumulation of empirical data. That is how the “scientific method” is meant to work, and often does. But the group selection controversy does not seem amenable to a straightforward empirical resolution; indeed, it is unclear whether there are any empirical disagreements at all between the opposing parties. Partly for this reason, the controversy has sometimes been dismissed as “semantic,” but this is too quick. There have been semantic disagreements, in particular over what constitutes a “group,” but this is not the whole story. For underlying the debate are deep issues to do with causality, a notoriously problematic concept, and one which quickly lands one in philosophical hot water.

All parties agree that differential group success is common in nature. Dawkins uses the example of red squirrels being outcompeted by grey squirrels. However, as he intuitively notes, this is not a case of genuine group selection, as the success of one group and the decline of another was a side-effect of individual level selection. More generally, there may be a correlation between some group feature and the group’s biological success (or “fitness”); but like any correlation, this need not mean that the former has a direct causal impact on the latter. But how are we to distinguish, even in theory, between cases where the group feature does causally influence the group’s success, so “real” group selection occurs, and cases where the correlation between group feature and group success is “caused from below”? This distinction is crucial; however it cannot even be expressed in terms of the standard formalisms that biologists use to describe the evolutionary process, as these are statistical not causal. The distinction is related to the more general question of how to understand causality in hierarchical systems that has long troubled philosophers of science.

Recently, a number of authors have argued that the opposition between kin and multi-level (or group) selection is misconceived, on the grounds that the two are actually equivalent—a suggestion first broached by W.D. Hamilton as early as 1975. Proponents of this view argue that kin and multi-level selection are simply alternative mathematical frameworks for describing a single evolutionary process, so the choice between them is one of convention not empirical fact. This view has much to recommend it, and offers a potential way out of the Wilson/Dawkins impasse (for it implies that they are both wrong). However, the equivalence in question is a formal equivalence only. A correct expression for evolutionary change can usually be derived using either the kin or multi-level selection frameworks, but it does not follow that they constitute equally good causal descriptions of the evolutionary process.

This suggests that the persistence of the group selection controversy can in part be attributed to the mismatch between the scientific explanations that evolutionary biologists want to give, which are causal, and the formalisms they use to describe evolution, which are usually statistical. To make progress, it is essential to attend carefully to the subtleties of the relation between statistics and causality.

Image Credit: “Selection from Birds and Animals of the United States,” via the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The post Kin selection, group selection and altruism: a controversy without end? appeared first on OUPblog.

What does astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson recommend for reading? According to Brain Pickings, Tyson (pictured, via) participated in a Reddit AMA session and named the books he feels “every intelligent person on the planet should read.”

What does astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson recommend for reading? According to Brain Pickings, Tyson (pictured, via) participated in a Reddit AMA session and named the books he feels “every intelligent person on the planet should read.”

Below, we’ve collected links to download free digital editions for all eight titles which include a mix of both fiction and nonfiction choices. Will you be tackling Tyons’s suggestions in the year 2015?

(more…)

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Add a Comment

Two of the biggest scientific breakthroughs in paleoanthropology occurred in 2010. Not only had we determined a draft genome of an extinct Neandertal from bones that lay in the Earth for tens of thousands of years, but the genome from another heretofore unknown ancient human relative, dubbed the Denisovans, was also announced.

A one-hundred-year-old conundrum was finally answered: did we mate with Neandertals? It was now undeniable that modern humans, with all our modern features – our rounded craniums, prominent chins, gracile faces tucked beneath an enlarged forehead, and long, slender skeletons – had met and mated with both of these extinct ancient human-like beings. After comparison with the human genome, 2-4% of the genomes of all peoples outside Africa had been directly inherited from Neandertal ancestors. And, DNA from the Denisovans (named after the cave in southern Siberia where their bones were discovered) makes up 3% to 6% of the genomes of many peoples living in South East Asia (Philippines, Melanesians, Australian Aborigines).

We now believe that it is in the Levant, regions just east of the Mediterranean, where humans met and mated with Neandertals. Remains of Neandertals are well known from this region. When modern humans ventured out of Africa into the Levant approximately 50,000 years ago, they mated with Neandertals. When they later spread into South East Asia they mated with Denisovans, although mating probably occurred in other regions of Asia as well. We now have evidence suggesting the ancient Denisovans occupied a very large geographic distribution extending from Southern Siberia all the way to the South East Asian tropics. It is tantalizing that, other than their distinctive genomes and their somewhat robust-looking molars, we know close to nothing about what they looked like.

With these discoveries, the notion that modern humans would hardly have interbred with such dim-witted, brutish, and bent-kneed Neandertals – a reputation that had long dogged Neandertals since French Paleontologist Marcellin Boule studied them – was now clearly out of the question. Indeed, more recent research into the skeleton and the cultural artifacts of Neandertals has demonstrated their sophisticated material cultures (stone tools, body ornament, and symbolic culture) and that their skeletons, rather than being “primitive,” were adapted for the cold and for rugged daily physical activities. Furthermore, the almost paradigmatically-held view of a strict replacement of ancient peoples in Eurasia by colonizing modern humans is now laid to rest. This view, popularized in the 1980s and 1990s, rested on comparisons between the minute mitochondrial genomes (much less than 1% of our full genomes) of humans and Neandertals. Full genomes, as you can see, tell us a fuller and more fascinating story.

These breakthroughs open a window of fresh air into the field of anthropology after decades of speculation. They are simultaneous with advancements in detecting the genetic bases of common chronic human diseases like hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. Yet even these diseases have been shaped by our evolutionary past. Genomes tell us that our species has undergone contractions in population size during the evolutionary past, which reduced the effectiveness of natural evolutionary constraints, and allowed damaging mutations to slip through the cracks to take root in our genome. This is a new view of disease informed by evolution as well as genomes.

We are also making base-by-base comparisons of our genome with those of chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, as well as genomes of other primates, allowing us to start to look for the genomic bases of our unique features – our large and complex brains, our complex cognition, and our use of spoken language. At the same time, we are learning the degree to which there is a genetic continuum between us and our primate relatives. Darwin presciently wrote in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” Today, we are realizing Darwin’s dream.

We are also uncovering details about how different human populations adapted to hot and cold climates, high altitudes, different diets, and to the various pathogens modern humans encountered as we colonized different regions of the world. A large project is already well-underway to collect thousands of genomes of modern peoples from different regions of the world. Comparing these genomes allows the search for ancient footprints left by positive selection (the type of natural selection that shapes our adaptations). Surprisingly, the different pathogens we encountered as we left Africa and spread into different environments appears to have made some of the largest footprints on our genome.

The genomic highway has an unchecked speed limit; we are experiencing a unique problem where data is pouring in faster than it can be fully analyzed. Each new issue of our scientific journals is ripe with new, exciting discoveries unlocking intriguing secrets of our ancestry.

The post Meeting and mating with our ancient cousins appeared first on OUPblog.

Sometimes what is considered edible is subject to a given culture or region of the world; what someone from Nicaragua would consider “local grub” could be entirely different than what someone in Paris would eat. How many different types of meat have you experienced? Are there some types of meat you would never eat? Below are nine different types of meat, listed in The Oxford Companion to Food, that you may not have considered trying:

Camel: Still eaten in some regions, a camel’s hump is generally considered the best part of the body to eat. Its milk, a staple for desert nomads, contains more fat and slightly more protein than cow’s milk.

Beaver: A beaver’s tail and liver are considered delicacies in some countries. The tail is fatty tissue and was greatly relished by early trappers and explorers. Its liver is large and almost as tender and sweet as a chicken’s or a goose’s.

Agouti: Also spelled aguti; a rodent species that may have been described by Charles Darwin as “the very best meat I ever tasted” (though he may have been actually describing a guinea pig since he believed agouti and cavy were interchangeable names).

Armadillo: Its flesh is rich and porky, and tastes more like possum than any other game. A common method of cooking is to bake the armadillo in its own shell after removing its glands.

Capybara: The capybara was an approved food by the Pope for traditional “meatless” days, probably since it was considered semiaquatic. Its flesh, unless prepared carefully to trim off fat, tastes fishy.

Hedgehog: A traditional gypsy cooking method is to encase the hedgehog in clay and roast it, after which breaking off the baked clay would take the spines with it.

Alligator: Its meat is white and flaky, likened to chicken or, sometimes, flounder. Alligators were feared to become extinct from consumption, until they started becoming farmed.

Iguana: Iguanas were an important food to the Maya people when the Spaniards took over Central America. Its eggs were also favored, being the size of a table tennis ball, and consisted entirely of yolk.

Puma: Charles Darwin believed he was eating some kind of veal when presented with puma meat. He described it as, “very white, and remarkably like veal in taste”. One puma can provide a lot of meat, since each can weigh up to 100 kg (225 lb).

Has this list changed the way you view these animals? Would you try alligator meat but turn your nose up if presented with a hedgehog platter?

Headline Image: Street Food at Wangfujing Street. Photo by Jirka Matousek. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Nine types of meat you may have never tried appeared first on OUPblog.

Each year the Royal Society awards a prize to the best book that communicates science to young people with the aim of inspiring young people to read about science. In the run up to the announcement of the winner of The Royal Society Young People’s Book Prize in the middle of November, I’ll be reviewing the books which have made the shortlist, and trying out science experiments and investigating the world with M and J in ways which stem from the books in question.

Each year the Royal Society awards a prize to the best book that communicates science to young people with the aim of inspiring young people to read about science. In the run up to the announcement of the winner of The Royal Society Young People’s Book Prize in the middle of November, I’ll be reviewing the books which have made the shortlist, and trying out science experiments and investigating the world with M and J in ways which stem from the books in question.

First up is What makes you YOU? by Gill Arbuthnott , illustrated by Marc Mones.

First up is What makes you YOU? by Gill Arbuthnott , illustrated by Marc Mones.

Have you ever thought how your genes could get you out of prison?

Or what the consequences might be if a company owned and could make money out of one of your own genes?

How would you know if you were a clone?

Why might knowing something about junk DNA be important if you’re running an exclusive restaurant with slightly dodgy practices?

Answers to these and many other intriguing questions are to be found in this accessible introduction to genetics, pitched at the 9-11 crowd. Arbuthnott does a great job of showing how relevant a knowledge of genetics is, whether in helping us to understand issues in the news (e.g. ‘Cancer gene test ‘would save lives’‘) or understanding why we are partly but not entirely like our parents. What makes you YOU? covers key scientists in the past history of genetics and crucial stages in its development as a science, including the race to discover what DNA looked like, the Human Genome Project, and Dolly the Sheep.

Arbuthnott portrays the excitement and potential in genetic research very well, leaving young readers feeling that this is far from a dry science; there are many ethical issues which make the discussion of the facts seem more relevant and real to young readers. Whilst on the whole I felt the author did a good job of balancing concerns with opportunities, I was sorry that in the discussion about genetically modified plants no mention was made of businesses ability to control supply to food stock, by creating plants which don’t reproduce, leaving farmers dependent on buying new seed from the business.

A timeline of discoveries, a very helpful list of resources for further study, a glossary and an index all make this a really useful book. Importantly, not only does the book contain interesting and exciting information, it also looks attractive and engaging. Lots of full bleed brightly coloured pages, and the use of cartoony characters make the book immediately approachable and funny – a world away from a dry dull school textbook.

What makes you YOU? provides a clear and enjoyable introduction to understanding DNA and many of the issues surrounding genetic research, perfect not only for learning about this branch of science, but also for generating discussion.

Extracting DNA is what the kids wanted to try after sharing What makes you YOU?. In the interest of scientific exploration we tried two different techniques to see which one we found easier and which gave the best results.

What you’ll need:

We learned this method for extracting DNA from Exploratopia by Pat Murphy, Ellen Macaulay and the staff of the Exploratorium. Unfortunately it’s out of print now, but it is definitely worth tracking down a copy if you are interested in doing experiments at home.

This second method is detailed in What makes you YOU? and involves strawberries, fresh pineapple, warm water and ice as well as washing-up liquid and salt. It also calls for methylated spirits but we swapped this for surgical spirit, as that’s what we had to hand.

This method is a little more involved than the first method but is a all round sensory experience: There are lots of strong smells (from crushed strawberries and puréed pineapple, as well as the surgical spirit), colours make it visually very appealing (perhaps this is why methylated spirits are called for in the original recipe as the purple of the meths adds another dimension) and there is also lots to feel, from the strange sensation of squishing the strawberries by hand, through to the different temperatures of the warm water in which the DNA-extracting-mix gently cooks followed by the ice water in which it cools down.

Look! Strawberry DNA!

Both methods were fun to try. We liked the first method because the result was seeing globs of our very own DNA, but the second method was a much more stimulating process, appealing to all the senses. Indeed this DNA extraction recipe alone makes it worthwhile seeking out a copy of What makes you YOU?.

Whilst extracting DNA we listened to:

The DNA song

Other activities which might go well with reading What makes you YOU? include:

What do you and your family look for in science books to really hook you in? Do share some examples of science books which you’ve especially enjoyed over the years.

Disclosure: I received a free review copy of What makes you YOU? from the Royal Society.

We tend to think of ‘science’ and ‘literature’ in radically different ways. The distinction isn’t just about genre – since ancient times writing has had a variety of aims and styles, expressed in different generic forms: epics, textbooks, lyrics, recipes, epigraphs, and so forth. It’s the sharp binary divide that’s striking and relatively new. An article in Nature and a great novel are taken to belong to different worlds of prose. In science, the writing is assumed to be clear and concise, with the author speaking directly to the reader about discoveries in nature. In literature, the discoveries might be said to inhere in the use of language itself. Narrative sophistication and rhetorical subtlety are prized.

This contrast between scientific and literary prose has its roots in the nineteenth century. In 1822 the essayist Thomas De Quincey broached a distinction between the ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power.’ As De Quincey later explained, ‘the function of the first is to teach; the function of the second is to move.’ The literature of knowledge, he wrote, is left behind by advances in understanding, so that even Isaac Newton’s Principia has no more lasting literary qualities than a cookbook. The literature of power, on the other hand, lasts forever and draws out the deepest feelings that make us human.

The effect of this division (which does justice neither to cookbooks nor the Principia) is pervasive. Although the literary canon has been widely challenged, the university and school curriculum remains overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of key authors and texts. Only the most naive student assumes that the author of a novel speaks directly through the narrator; but that is routinely taken for granted when scientific works are being discussed. The one nineteenth-century science book that is regularly accorded a close reading is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). A number of distinguished critics have followed Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots in attending to the narrative structures and rhetorical strategies of other non-fiction works – but surprisingly few.

It is easy to forget that De Quincey was arguing a case, not stating the obvious. A contrast between ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power’ was not commonly accepted when he wrote; in the era of revolution and reform, knowledge was power. The early nineteenth century witnessed remarkable experiments in literary form in all fields. Among the most distinguished (and rhetorically sophisticated) was a series of reflective works on the sciences, from the chemist Humphry Davy’s visionary Consolations in Travel (1830) to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33). They were satirised to great effect in Thomas Carlyle’s bizarre scientific philosophy of clothes, Sartor Resartus (1833-34).

These works imagined new worlds of knowledge, helping readers to come to terms with unprecedented economic, social, and cultural change. They are anything but straightforward expositions or outdated ‘popularisations’, and deserve to be widely read in our own era of transformation. Like the best science books today, they are works in the literature of power.

James Secord is Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project, and a fellow of Christ’s College. His research and teaching is on the history of science from the late eighteenth century to the present. He is the author of the recently published Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post When science stopped being literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Beloved children’s author Astrid Lindgren will appear on Sweden’s 20 krona note.

Beloved children’s author Astrid Lindgren will appear on Sweden’s 20 krona note.

The Riksbank, Sweden’s central bank, announced this news back in 2011. They plan to start distributing the note sometime between 2014 and 2015.

Artist Göran Österlund designed the note and included a drawing of Lindgren’s revered heroine Pippi Longstocking into the final image. BuzzFeed reports that 20 Krona can be exchanged for about $3 USD.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Add a Comment

Does the universe have a purpose? Physicist and author Neil deGrasse Tyson responded to that cosmic question in the video embedded above–do you agree with his answer?

Last year, Tyson answered another question that matters to all Galleycat readers: “Which books should be read by every single intelligent person on the planet?” The famous physicist and author responded with a concise list of classic books. Follow the links below to download free ePub, Kindle or text versions of the books.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Add a Comment

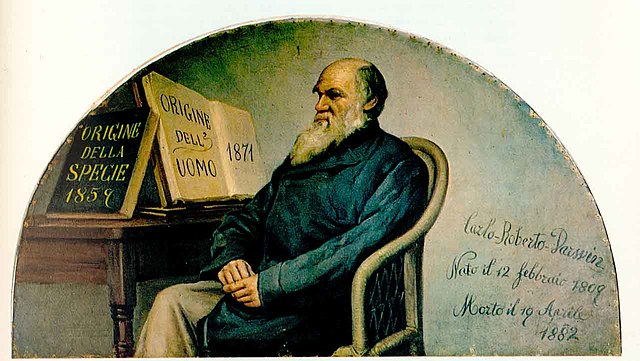

Italian panel depicting Charles Darwin, created ca. 1890, on display at the Turin Museum of Human Anatomy. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Today is Darwin’s birthday. It’s doubtful that any scientist would deny Darwin’s importance, that his work provides the field of biology with its core structure, by providing a beautiful, powerful mechanism to explain the diversity of form and function that we see all around us in the living world. But being of importance to one’s field is only one way we judge a scientist’s contributions. There is also the matter of how their work has changed lives all over the world, even of those who don’t know or necessarily care about their accomplishments. What has Darwin done for his fellow human beings? Why should they care about what he showed us, or want to learn what he had to teach?

Understanding evolution is challenging, for many reasons. We often point to the religious questions raised by his work as the cause of these difficulties, but there are many more. No creature decides to change their DNA, nor can a species foresee what they should become to survive, but it sure seems like they do. Evolution provides such elegant solutions to incredibly complex problems, it’s hard to see them as the product of random variation and selection. Even for people who lack religious convictions that make evolution discomforting, it’s hard to grasp the mechanisms of evolution. This difficulty arises out of developmental constraints that lead us to look for centralized, intentional agents when we make causal attributions. It comes out of the challenges inherent in altering our conceptions of the world and replacing one belief system with another, and out of the emotional reaction we have to facing the reality that we are not special or superior to our biological cousins, nor are we in control of the fate of our species in generations to come.

If we’re going to ask people to expend the time and effort it requires to wrap their heads around a idea like biological evolution, it seems as though there ought to be a really big payoff for all that work. So, what does learning about evolution get us?

We’ve asked this question to quite a few teachers, biologists, philosophers, and educational researchers along the course of several projects, the most extensive and recent being the one that led to the edited volume OUP will be putting out soon on teaching and learning about evolution. The reaction is almost always the same. First, there is the pause, as they blink, startled that anyone would be asking such a thing. Often they call upon evolution’s importance to science, and its beauty and elegance — who wouldn’t want to spend their time contemplating that? But if pushed back, and asked what practical value they could point to that would make the struggle of mastering these complex ideas worthwhile, they have a hard time coming up with an answer. The most common responses revolve around the (mis)use of antibiotics, and that people need to know that taking these drugs too often could cause real long-term harm. The second most popular argument is that people should understand the importance of biodiversity, how fragile species become when their gene pool dwindles and ecological balances are disrupted, and that being a part of nature — not above it — comes with responsibili